辽观搬运、翻译、整合的中英文维基百科词条。与原维基百科词条同样遵循CC-BY-SA 4.0协议,在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。

中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目(点击这里了解更多),其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

封面图片:This is a photo of a monument in Thailand identified by the ID

参考译文:这是一张通过ID识别d 泰国纪念碑的照片

图片作者:Preecha.MJ 此图片遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议

目录

0. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、翻译、整合过程中添加的。

0.1 图片集(地标、地图、徽标)

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、翻译、整合过程中添加的。

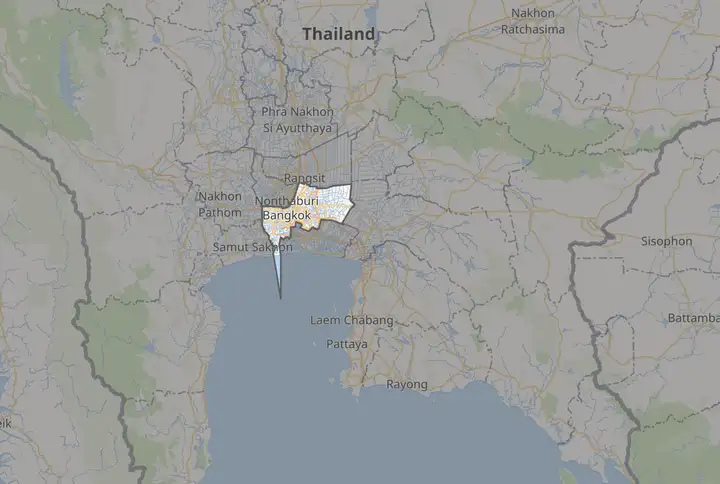

图片题注:曼谷 บางกอก(泰语) Bangkok(英语) 恭贴玛哈纳空 กรุงเทพมหานคร(泰语) Krung Thep Maha Nakhon的位置

图片作者:NordNordWest – self-made, using Thailand location map.svg

坐标:13°45′N 100°31′E

0.1 概况表格

| 国家 | 泰国 |

|---|---|

| Region(区域) | Central Thailand (泰国中部) |

| 省份 | 曼谷直辖市 |

| 建立 | 大城王国时代 |

| Settled(建城) | c. 15th century(公元15世纪) |

| 定都于 | 1782年4月21日 |

| Re-incorporated(重新成为实体) | 13 December 1972 1972 年 12 月 13 日 |

| Founded by(创建者) | King Rama I(拉玛一世国王) |

| 政府 | |

| Governing body(管理机构) | Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (曼谷大都会管理局) |

| • Type(类型) | Special administrative area(特别行政区) |

| • 市长 | 查察·西提潘 |

| 面积 | |

| • 首都、特别直辖市 | 1,568.737 平方千米(605.693 平方英里) |

| • 都会区 | 7,761.50 平方千米(2,996.73 平方英里) |

| 人口(2019年) | |

| • 首都、特别直辖市 | 10,820,921人 |

| • 密度 | 5,300人/平方千米(14,000人/平方英里) |

| • 都会区 | 10,624,700 |

| • 都会区密度 | 1,900人/平方千米(5,000人/平方英里) |

| 时区 | 印度支那时间(UTC+7) |

| ISO 3166-2 | TH-10 |

| Postal code(邮政编码) | 10### |

| Area code(地区代码) | 02 |

| Website(网站) | main.bangkok.go.th |

| 年平均气温 | 30 °C |

图片题注:Bangkok, Thailand View from the State Tower

图片作者:Ninara from Helsinki, Finland

参考译文:从国家塔看泰国曼谷。

0.2 文字说明

曼谷(泰语:บางกอก,英语:Bangkok)官方名字恭贴玛哈纳空[2](泰语:กรุงเทพมหานคร,转写:krung deːb mahaː nagara,皇家转写:Krung Thep Maha Nakhon,国际音标:[krūŋ tʰêːp mahǎː nákʰɔ̄ːn]聆听ⓘ),泰国口语简称恭贴[3](泰语:กรุงเทพ,皇家转写:Krung Thep,国际音标:[krūŋ tʰêːp],聆听ⓘ),是泰国的首都和最大的城市,当地的华人又称泰京,曼谷为泰国的政治、经济、贸易、交通、文化、科技、教育和各方面的中心。在2020年的人口普查中,曼谷就有约为1053.9万人,占泰国总人口的15.3%。2010年人口普查中,超过1400万人,即约有22.2%人居住于曼谷的都市郊区。曼谷市位于昭披耶河的东岸,邻近泰国湾。

曼谷的历史可以追溯到15世纪的阿瑜陀耶王国时期的一个小型贸易站,该站最终发展成为两个首都城市的所在地,分别是1768年的吞武里王国和1782年的拉达那哥欣王国,后在暹罗现代化的统治之下,曼谷于19世纪后期开始进行都市发展,由于面临来自西方的压力,最终暹罗更名为泰国。而曼谷也在整个20世纪成为泰国政治斗争的中心,并经历了泰国废除绝对君主制采用宪政、多次政变和几次起义等历史事件。1972年,曼谷被纳入特别行政区,并在1960年代至1980年代迅速发展,对泰国的政治、经济、教育、媒体和现代社会产生了重大影响。

1980年代和1990年代的亚洲投资热潮期间,许多跨国公司将其地区总部设在曼谷。因此这座城市现在是金融和商业的区域重镇。它是交通和医疗保健的国际枢纽,并已成为艺术、时尚和娱乐中心。依照全球化及世界城市研究网络(GaWC)所公布之“世界级城市”名单中,曼谷被列为与斯德哥尔摩、苏黎世、旧金山、维也纳等同属于Alpha−级别的国际都市,此外这座城市以其街头生活和文化地标以及红灯区而闻名。成为是世界顶级旅游目的地之一,也经常评为世界上访问量最大的城市。

近年,由于曼谷的快速增长缺乏城市规划,导致曼谷城市景观杂乱无章,基础设施不足。尽管高速公路网络广泛,但道路脉络不足和大量私家车使用导致长期严重的交通拥堵,从而在1990年代造成严重的空气污染。为了解决这个问题,该市已经转向公共交通,运营了8条城市铁线路并建设其他公共交通,由于气候变迁,这座城市也面临着海平面上升等长期环境威胁。

图片题注:Grand Palace Bangkok, Thailand

图片作者:Andy Marchand

参考译文:泰国曼谷大皇宫

1. 名称 | Name

曾先后被称为曼谷、吞武里、拉达那哥欣、帕那空、恭贴吞武里、恭贴玛哈纳空[3]。以前华人也称暹京。

而2022年2月,泰国皇家学会宣布将曼谷的官方名称更名为恭贴玛哈纳空(英语:Krung Thep Maha Nakhon),但同时继续承认曼谷一词。[2]

1.1 曼谷的词源

辽观注:以下内容中,中英文词条内容存在冲突,请在阅读时自行判断。

The origin of the name Bangkok (บางกอก, pronounced in Thai as [bāːŋkɔ̀ːk]ⓘ) is unclear. Bangบาง is a Thai word meaning ‘a village on a stream’,[13] and the name might have been derived from Bang Ko (บางเกาะ), koเกาะ meaning ‘island’, stemming from the city’s watery landscape.[9] Another theory suggests that it is shortened from Bang Makok (บางมะกอก), makokมะกอก being the name of Elaeocarpus hygrophilus, a plant bearing olive-like fruit.[d] This is supported by the former name of Wat Arun, a historic temple in the area, that used to be called Wat Makok.[14]

参考译文:曼谷(Bangkok)的名称来源不明确。”Bang”(บาง)是泰语中的一个词,意思是“溪边的村庄”,而这个名称可能源于“Bang Ko”(บางเกาะ),其中“Ko”(เกาะ)指的是“岛屿”,这与曼谷多水的地形有关。另一种理论认为,它缩短自“Bang Makok”(บางมะกอก),其中“Makok”(มะกอก)是一种结出橄榄状果实的植物(Elaeocarpus hygrophilus)的名称。这一观点得到了曼谷地区历史悠久的寺庙Wat Arun曾经被称为Wat Makok的支持。

图片题注:Wat Phra Kaew, viewed from the Outer Court of the Grand Palace, just inside the Wisetchaisi Gate. Also known as the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, it is Thailand’s primary Buddhist temple. Located within the grounds of the Grand Palace, Wat Phra Kaew is technically a royal chapel, as unlike regular temples it does not include living quarters for Buddhist monks. Edit by me, User:TSP, of File:Wat_Phra_Kaew_by_Ninara_(33271955941).jpg as permitted by the CC-BY licence of that file.

图片作者:Original image: Ninara from Helsinki, Finland. Edit: TSP

参考译文:玉佛寺(Wat Phra Kaew),从大皇宫外廷看到的,就在 Wisetchaisi 门内。 又称玉佛寺,是泰国主要的佛教寺庙。 玉佛寺位于大皇宫内,严格来说是一座皇家礼拜堂,因为与普通寺庙不同,它不包括佛教僧侣的居住区。 由我(用户:TSP)编辑文件:Wat_Phra_Kaew_by_Ninara_(33271955941).jpg,经该文件的 CC-BY 许可证许可。

因为曼谷有很多运河将城市切为岛,而且像威尼斯全年洪灾频发,“曼谷”本来是泰语“บางเกาะ”(Bangko; [bāːŋ kɔ̀ʔ])的音译,“曼”的意思是“河”;“谷”的意思是“岛”,合起来就是“河滨岛村”。那莱大帝时期,法国工程师得拉玛(法语:De Lamar)为泰国设计了曼谷星形要塞,并注明位于曼谷岛(法语:Î. de Bangkok)。法国人在翻译 “Bangkok” (บางกอก; [baŋkok])一词时,将词尾的 /ʔ/ 改成 /k/ 以便于发音。建立首都时期,城市内主要族群以潮州人为主,他们按照潮阳话的发音,将“Bangkok”译作“曼谷”[3]。越南人则将这个词音译成“望阁”(Vọng Các)。

Officially, the town was known as Thonburi Si Mahasamut (ธนบุรีศรีมหาสมุทร, from Pali and Sanskrit, literally ‘city of treasures gracing the ocean’) or Thonburi, according to the Ayutthaya Chronicles.[15] Bangkok was likely a colloquial name, albeit one widely adopted by foreign visitors, who continued to use it to refer to the city even after the new capital’s establishment.

参考译文:根据古代的《大城王国编年史》,这座城市在正式上是以Thonburi Si Mahasamut(ธนบุรีศรีมหาสมุทร)的名字被称呼,这个名字来自巴利语和梵语,字面意思是“装饰海洋的珍宝之城”或者简称为Thonburi。然而,曼谷(Bangkok)很可能是一个口语化的名称,尽管这个名称被外国游客广泛接受,并且即使在新首都建立后,他们仍然使用这个名称来指代这座城市。

When King Rama I established his new capital on the river’s eastern bank, the city inherited Ayutthaya’s ceremonial name, of which there were many variants, including Krung Thep Thawarawadi Si Ayutthaya (กรุงเทพทวารวดีศรีอยุธยา) and Krung Thep Maha Nakhon Si Ayutthaya (กรุงเทพมหานครศรีอยุธยา).[16] Edmund Roberts, visiting the city as envoy of the United States in 1833, noted that the city, since becoming capital, was known as Sia-Yut’hia, and this is the name used in international treaties of the period.[17]

参考译文:当拉玛一世国王在河的东岸建立了他的新首都时,这座城市继承了大城王国的仪式名称,其中有许多变种,包括Krung Thep Thawarawadi Si Ayutthaya(กรุงเทพทวารวดีศรีอยุธยา)和Krung Thep Maha Nakhon Si Ayutthaya(กรุงเทพมหานครศรีอยุธยา)。1833年,美国特使爱德蒙·罗伯茨(Edmund Roberts)访问这座城市时,注意到自成为首都以来,这座城市被称为Sia-Yut’hia,并且这是当时国际条约中使用的名称。

1.2 吞武里的词源

主条目:吞武里王朝

1542年,曼谷开始挖运河,并改名为“吞武里”,然而,一般泰国人仍然习惯称曼谷,甚至1767年,阿瑜陀耶王国首都阿瑜陀耶(พระนครศรีอยุธยา – Ayutthaya)被缅甸攻陷焚毁。郑昭国王便将首都移至吞武里,此时代泰国人已经习惯称此为吞武里。

拉玛二世和三世时期,城内增建和维修了许多佛寺,其中以帕彻独彭大寺院和金山寺为代表。在1865年,拉玛四世将城市切割为两省,左岸为吞武里省,右岸为拍那空省。朱拉隆功大帝时代,王宫群向北建设,并且拆除了大部分城墙;后任的国王继续往北建造宫殿。1916年建立了第一所大学,朱拉隆功大学。1971年两市再合并成为“恭贴吞武里”都市区,面积达290平方千米。1972年升级以直辖市,又称“恭贴玛哈纳空”,面积2000平方千米;新都心移往昭披耶河东岸,西岸现在被视为旧市区。

图片题注:Victory Monument

图片作者:Adam Lai

参考译文:胜利纪念碑

1.3 恭贴玛哈纳空的词源

主条目:拉达那哥欣岛

1782年扎克里王朝拉玛一世将首都从昭披耶河西岸的吞武里迁至昭披耶河东岸,在此造宫殿、修城墙,大皇宫和卧佛寺,是其中最杰出的代表,并兴建了最早的九条街道,以唐人街的三聘街最为著名。昭披耶河东岸从一个小型市集和港口开始发展。并命名为“拉达那哥欣”。仪式全名是由拉玛一世命名,后来拉玛四世做出修改,修改后的全称为:

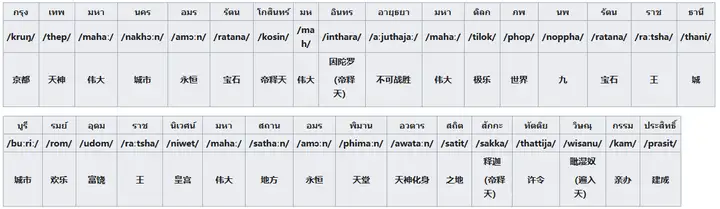

กรุงเทพมหานคร อมรรัตนโกสินทร์ มหินทรายุธยา มหาดิลกภพ นพรัตนราชธานีบูรีรมย์ อุดมราชนิเวศน์มหาสถาน อมรพิมานอวตารสถิต สักกะทัตติยวิษณุกรรมประสิทธิ์(泰语)(聆听ⓘ)[注 1][a]

(音译文) 恭贴玛哈纳空,阿蒙拉达纳戈信,玛欣他拉育他亚,玛哈迪洛朴,诺帕拉拉差他尼布里龙,乌东拉差尼韦玛哈沙探,阿蒙披曼阿瓦丹沙提,沙甲他迪亚威沙努甘巴西

注a:这个城市全名融合了两个古老的印度语言:巴利语和梵语。若使用这些语言的发音,其罗马拼音为Krung–dēvamahānagaraamararatnakosindramahindrāyudhyāmahātilakabhavanavaratanarājadhānīpūrīramyauttamarājanivēśana mahāsthānaamaravimānaavatārasthitya śakrasdattiya viṣṇukarmaprasiddhi聆听ⓘ

注1:皇家拉丁音译:”Krung Thep Maha Nakhon Amon Rattanakosin Mahintharayutthaya Mahadilokphop Noppharatratchathaniburirom Udomratchaniwetmahasathan Amonphimanawatansathit Sakkathattiyawitsanukamprasit”

其意译为:

“帝释天旨述、工巧天神筑,天子御驻,极宫浮出,九玉乐都,宏伟盛处,金汤天固,玉佛永属之天神京都”

曼谷全名已经被吉尼斯世界纪录登记为世界最长的地名(长达167个拉丁字母)[4][5]。

早期泰国小学曾教导学生背诵曼谷的全名,纵使极少数人会解释这个全名的意思(这些字都是古老的梵文借词),但近年已删除,民众日常生活也不使用全称。1989年,泰国阿撒尼-哇三兄弟乐队推出名为《Krung Thep Maha Nakhon》的歌曲,歌词将曼谷的全称重复数遍,该歌曲遂被多数泰国人用以背诵曼谷的全名。外界熟知“曼谷”(Bangkok)一名,各国均称泰国首都为“曼谷”,不熟悉“恭贴玛哈纳空”这一官方名称。

2. 历史 | History

Main article: History of Bangkok(主条目:曼谷历史)

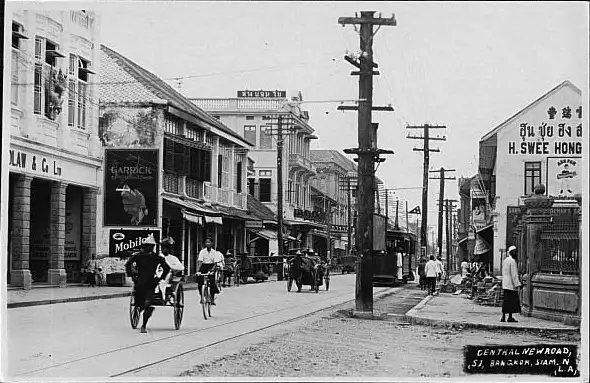

图片题注:石龙军路是曼谷的第一条现代马路

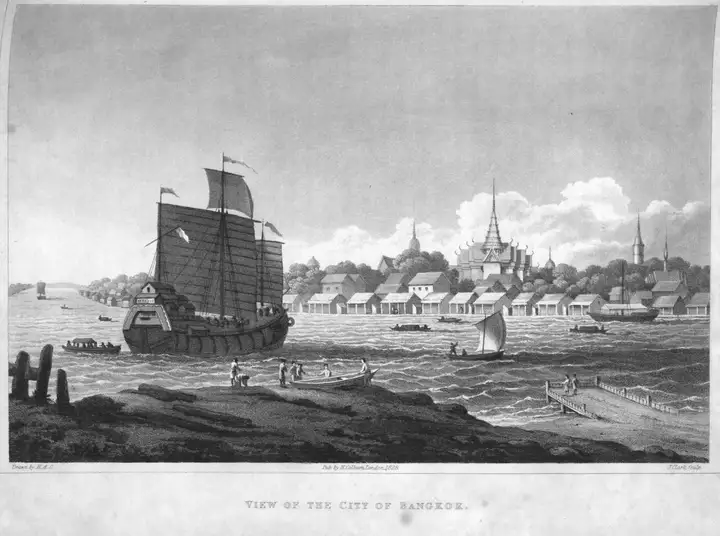

图片题注:Engraving of the city from British diplomat John Crawfurd‘s embassy in 1822

图片作者:John Crawfurd

参考译文:1822 年英国外交官约翰·克劳福德大使馆所藏的城市描绘

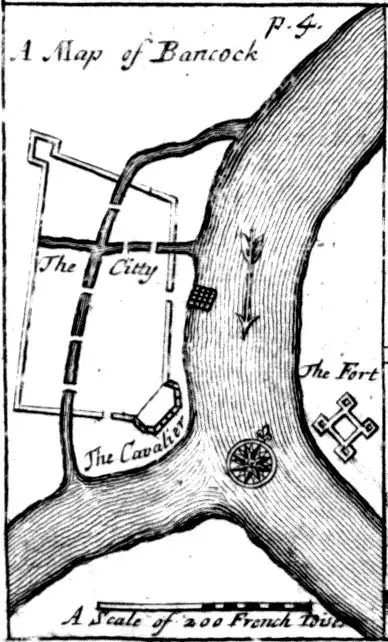

图片题注:Map of 17th-century Bangkok, from Simon de la Loubère‘s Du Royaume de Siam

参考译文:17 世纪曼谷地图,出自 Simon de la Loubère 的《Du Roi de Siam》

曼谷的历史最早可追溯至15世纪早期的阿瑜陀耶时代[6],该地靠近河口,战略位置重要,因而逐渐得到重视,形成贸易集镇。1685年至1687年,那莱王命法国工程师德拉马雷(de la Mare)在昭披耶河东岸修筑星形要塞,法军获准驻扎于此。1688年,暹罗爆发内乱,叛军包围曼谷要塞,将法军逐出暹罗。1767年,缅军攻破阿瑜陀耶,达信在昭披耶河西岸(今吞武里)建都,开创吞武里王朝。1782年,通銮建立扎克里王朝,定都在吞武里对岸的拉达那哥欣岛,是为今日曼谷城的基础。曼谷正式的建城日期定为1782年4月21日,是城中国柱树立的日子[7]。

到19世纪,曼谷逐渐成为东南亚的商业重镇,在同中国及西洋的贸易中受益。19世纪后期,暹罗国王蒙固和朱拉隆功推行西化改革,在曼谷修建马路和铁路,一改曼谷城过去倚靠水路交通的格局;引入蒸汽机、出版社,以及西式教育及医疗体系,令都城曼谷成为暹罗西化的样板。曼谷亦是暹罗权力斗争的中心地。1932年,暹罗军方及示威者在曼谷发动li4 xian4 ge2 ming4,终结了君主专制[8]。第二次世界大战期间,暹罗同日本结盟,因而曾遭盟军轰炸。战后的泰国成为美国盟友,曼谷得到美国援助及政府投资,从而快速成长,特别是由于成为越战美军的疗养地,旅游业获得发展。大量农村人口向城区迁移,曼谷的人口在20世纪60年代由180万激增至300万[8]。

Following the US withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973, Japanese businesses took over as leaders in investment, and the expansion of export-oriented manufacturing led to growth of the financial market in Bangkok.[11] Rapid growth of the city continued through the 1980s and early 1990s, until it was stalled by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. By then, many public and social issues had emerged, among them the strain on infrastructure reflected in the city’s notorious traffic jams. Bangkok’s role as the nation’s political stage continues to be seen in strings of popular protests, from the student uprisings in 1973 and 1976, anti-military demonstrations in 1992, and frequent street protests since 2006, including those by groups opposing and supporting former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra from 2006 to 2013, and a renewed student-led movement in 2020.[12]

参考译文:1973年美国从越南撤军后,日本企业接管了投资的领导地位,以出口为导向的制造业扩张推动了曼谷金融市场的增长。曼谷的快速增长持续到上世纪80年代和90年代初,直到1997年亚洲金融危机使其停滞。那时,许多公共和社会问题浮现出来,其中包括城市臭名昭著的交通拥堵反映出的基础设施紧张。曼谷作为国家的政治舞台的角色仍然在一系列的kang4 yi4活动中得以体现,包括1973年和1976年的学生起义、1992年的反军事shi4 wei1,以及自2006年以来的频繁街头kang4 yi4活动,包括2006年至2013年反对和支持前总理他信·西那瓦的团体,以及2020年再度由学生领导的运动。

泰国经济在战后形成出口导向的制造业体系,亦令曼谷金融市场不断扩大[8]。曼谷在20世纪80年代至90年代持续快速发展,但在1997年遭亚洲金融风暴重创。公共和社会问题自此不断显现,交通拥堵等问题饱受诟病。曼谷常年有zheng4 bian4和shi4 wei1发生,例如1991年、2006年、2014年的政变,及1973年、1976年、2010年、2013年至2014年、2020年至2022年的群众游行等[9]。

曼谷城的行政体系是在1906年,朱拉隆功统治时期确立,是为蒙通体系,曼谷属恭贴玛哈那空蒙通。1915年,又细分为数个省份。1972年,曼谷大都会管理局成立,作为曼谷的管治机构延续至今;翌年,昭披耶河东岸的拍那空省和西岸的吞武里省正式合并,形成今日曼谷特别直辖市之格局[7]。

3. 政府 | Government

Main article: Bangkok Metropolitan Administration(主条目:曼谷市政府)

图片题注:The city’s ceremonial name is displayed in front of Bangkok City Hall.

图片作者:Suasysar

参考译文:曼谷市政厅前展示着这座城市的礼仪名称。

The city of Bangkok is locally governed by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA). Although its boundaries are at the provincial (changwat) level, unlike the other 76 provinces Bangkok is a special administrative area whose governor is directly elected to serve a four-year term. The governor, together with four appointed deputies, form the executive body, who implement policies through the BMA civil service headed by the Permanent Secretary for the BMA. In separate elections, each district elects one or more city councillors, who form the Bangkok Metropolitan Council. The council is the BMA’s legislative body, and has power over municipal ordinances and the city’s budget.[22] The latest gubernatorial election took place on 22 May 2022 after an extended lapse following the 2014 Thai coup d’état, and was won by Chadchart Sittipunt.[23]

参考译文:曼谷市由曼谷都会管理局(BMA)进行地方治理。尽管其边界处于省级(府级)水平,但与其他76个省份不同,曼谷是一个特别行政区,其州长直接选举产生,任期为四年。州长与四名指定的副州长共同组成行政机构,通过BMA市政服务机构实施政策,该机构由BMA常任秘书长领导。在单独的选举中,每个区选举一个或多个城市议员,他们组成曼谷都会议会。议会是BMA的立法机构,对市政法规和市政预算具有权力。最新的州长选举于2022年5月22日举行,在2014年泰国政变之后经过长时间的间隔,并由查德查特·西提蓬(Chadchart Sittipunt)获胜。

Bangkok is divided into fifty districts (khet, equivalent to amphoe in the other provinces), which are further subdivided into 180 sub-districts (khwaeng, equivalent to tambon). Each district is managed by a district director appointed by the governor. District councils, elected to four-year terms, serve as advisory bodies to their respective district directors.

参考译文:曼谷分为50个区(khet,相当于其他省份的县),每个区进一步分为180个副区(khwaeng,相当于乡)。每个区由州长任命的区长管理。区议会选举产生,任期为四年,作为各自区长的咨询机构。

The BMA is divided into sixteen departments, each overseeing different aspects of the administration’s responsibilities. Most of these responsibilities concern the city’s infrastructure, and include city planning, building control, transportation, drainage, waste management and city beautification, as well as education, medical and rescue services.[24] Many of these services are provided jointly with other agencies. The BMA has the authority to implement local ordinances, although civil law enforcement falls under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police Bureau.

参考译文:曼谷都会管理局(BMA)分为十六个部门,每个部门负责管理行政职责的不同方面。其中大部分职责涉及城市基础设施,包括城市规划、建筑控制、交通、排水、废物管理和城市美化,以及教育、医疗和救援服务。许多这些服务是与其他机构共同提供的。BMA有权实施当地法规,尽管民事执法属于大都会警察局的管辖范围内。

The seal of the city shows Hindu god Indra riding in the clouds on Airavata, a divine white elephant known in Thai as Erawan. In his hand Indra holds his weapon, the vajra.[25] The seal is based on a painting done by Prince Naris. The tree symbol of Bangkok is Ficus benjamina.[26] The official city slogan, adopted in 2012, reads:

参考译文:曼谷的市徽展示了印度教神祇因陀罗骑着空中的神圣白象艾洛瓦纳(在泰语中称为伊洛瓦特)的形象。因陀罗手持他的武器金刚杵。市徽的设计基于Prince Naris所绘的一幅画作。曼谷的象征树是榕树(Ficus benjamina)。市的官方口号于2012年采用,中文翻译为:

As built by deities, the administrative centre, dazzling palaces and temples, the capital of Thailand

参考译文:由神灵建造的行政中心,令人眼花缭乱的宫殿和寺庙,泰国的首都,曼谷。

กรุงเทพฯ ดุจเทพสร้าง เมืองศูนย์กลางการปกครอง วัดวังงามเรืองรอง เมืองหลวงของประเทศไทย[27]

As the capital of Thailand, Bangkok is the seat of all branches of the national government. The Government House, Parliament House and Supreme, Administrative and Constitutional Courts are all in the city. Bangkok is the site of the Grand Palace and Dusit Palace, respectively the official and de facto residence of the king. Most government ministries also have headquarters and offices in the capital.

参考译文:作为泰国的首都,曼谷是全国政府各个部门的所在地。政府总部、国会大厦以及最高行政法院和宪法法院都位于这座城市。曼谷还是大皇宫和都喜庭宫的所在地,分别是国王的官方和事实上的住所。大多数政府部门也在首都设有总部和办公室。中文翻译为:

4. 地理 | Geography

曼谷面积为 1,568.7 平方千米(605.7 平方英里),在泰国其他76个省份中排名第69位。其中,约700平方千米(270 平方英里)的区域形成建成市区。市区面积居世界第73位。该市的城市扩张延伸到与其接壤的其他六个省份的部分地区,即从西北顺时针顺序:暖武里府、巴吞他尼府、北柳府、北榄府、北沙空府和佛统府。除北柳府外,这些省份与曼谷一起构成了更大的曼谷都会区[24]。

曼谷地处平原,位于昭拍耶河(俗称湄南河)流域。该河被称为曼谷的母亲河,全长372千米,曼谷市内繁忙的水上交通使曼谷有“东方威尼斯”的美称。

曼谷的平均海拔2米左右,这使得曼谷经常在雨季面临洪水的困扰。大雨过后,曼谷的街道经常会出现积水。

4.1 地形 | Topography

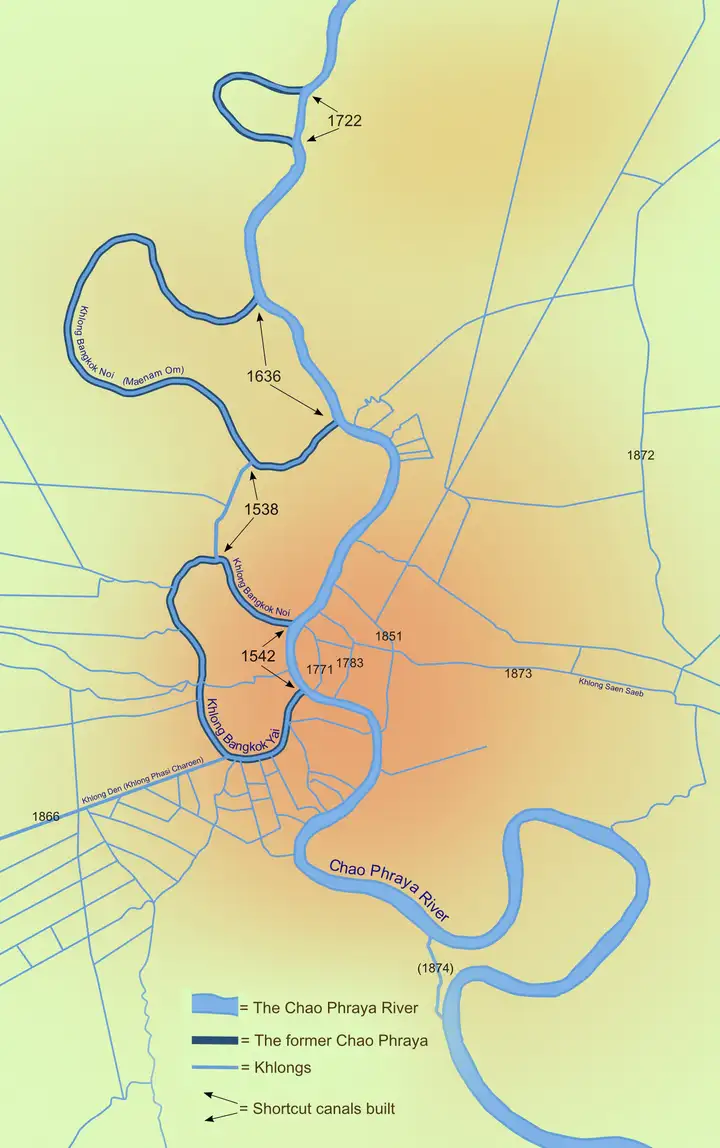

图片题注:Bangkok’s major canals are shown in this map, detailing the original course of the river and its shortcut canals.

图片作者:Hdamm

参考译文:这张地图显示了曼谷的主要运河,详细介绍了河流的原始河道及其捷径运河。

Bangkok is situated in the Chao Phraya River delta in Thailand’s central plain. The river meanders through the city in a southerly direction, emptying into the Gulf of Thailand approximately 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of city centre. The area is flat and low-lying, with an average elevation of 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) above sea level.[3][h] Most of the area was originally swampland, which was gradually drained and irrigated for agriculture by the construction of canals (khlong) which took place from the 16th to 19th centuries. The course of the river as it flows through Bangkok has been modified by the construction of several shortcut canals.

参考译文:曼谷位于泰国中部平原的湄南河三角洲。湄南河蜿蜒穿过城市,向南流入距离市中心约25公里(16英里)的泰国湾。该地区地势平坦,平均海拔高度为1.5米(4英尺11英寸)以上[3][h]。大部分地区最初是沼泽地,通过从16世纪到19世纪修建的运河系统(khlong)逐渐被排干和灌溉用于农业。湄南河在穿过曼谷时的河道已经通过修建多条捷径运河进行了改变。中文翻译为:曼谷位于泰国中部平原的湄南河三角洲。湄南河在城市中蜿蜒向南流,最终在距离市中心约25公里的泰国湾入海。该地区地势平坦低洼,平均海拔高度为1.5米。大部分地区原先是沼泽地,经过16世纪至19世纪修建的运河系统的排水和灌溉,逐渐变成了农业用地。曼谷内的湄南河河道已经通过修建多条捷径运河而改变了其流向。

The city’s waterway network served as the primary means of transport until the late 19th century, when modern roads began to be built. Up until then, most people lived near or on the water, leading the city to be known during the 19th century as the “Venice of the East”.[29] Many of these canals have since been filled in or paved over, but others still criss-cross the city, serving as major drainage channels and transport routes. Most canals are now badly polluted, although the BMA has committed to the treatment and cleaning up of several canals.[30]

参考译文:直到19世纪末期修建现代道路之前,曼谷的水路网络是主要的交通方式。直到那时,大多数人住在水边或水上,因此在19世纪曼谷被称为“东方的威尼斯”[29]。许多这些运河后来被填平或铺设道路,但其他一些仍然穿越城市,充当主要的排水通道和交通路线。大部分运河现在都严重污染,尽管曼谷都市管理局承诺对几条运河进行治理和清理[30]。中文翻译为:直到19世纪末期修建现代道路之前,曼谷的水路网络是主要的交通方式。在那之前,大多数人居住在或靠近水边,因此在19世纪,曼谷被称为“东方的威尼斯”。许多运河后来被填平或铺设道路,但仍有一些交叉穿越城市,起着主要的排水和交通路线的作用。大部分运河现在严重污染,尽管曼谷都市管理局已承诺对一些运河进行治理和清理。

The geology of the Bangkok area is characterized by a top layer of soft marine clay, known as “Bangkok clay”, averaging 15 metres (49 ft) in thickness, which overlies an aquifer system consisting of eight known units. This feature has contributed to the effects of subsidence caused by extensive groundwater pumping. First recognized in the 1970s, subsidence soon became a critical issue, reaching a rate of 120 millimetres (4.7 in) per year in 1981. Ground water management and mitigation measures have since lessened the severity of the situation, and the rate of subsidence decreased to 10 to 30 millimetres (0.39 to 1.18 in) per year in the early 2000s, though parts of the city are now 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) below sea level.[31]

参考译文:曼谷地区的地质特征以一层厚度约为15米(49英尺)的软性海洋粘土层为特点,被称为“曼谷粘土”,位于包含八个已知层次的含水层系统之上。这一特征导致了由广泛的地下水抽取引起的沉降效应。这个问题在20世纪70年代被首次认识到,很快就变成了一个严重的问题,在1981年达到每年120毫米(4.7英寸)的沉降速率。地下水管理和缓解措施在此后减轻了情况的严重性,到了21世纪初,沉降速率降至每年10到30毫米(0.39到1.18英寸),尽管城市的部分地区现在已经低于海平面1米(3英尺3英寸)[31]。

Subsidence has resulted in increased flood risk, as Bangkok is already prone to flooding due to its low elevation and an inadequate drainage infrastructure,[32][33] often compounded by blockage from rubbish pollution (especially plastic waste).[34] The city now relies on flood barriers and augmenting drainage from canals by pumping and building drain tunnels, but parts of Bangkok and its suburbs are still regularly inundated. Heavy downpours resulting in urban runoff overwhelming drainage systems, and runoff discharge from upstream areas, are major triggering factors.[35] Severe flooding affecting much of the city occurred in 1995 and 2011. In 2011, most of Bangkok’s northern, eastern and western districts were flooded, in some places for over two months.

参考译文:由于地面下沉,曼谷的洪水风险增加,因为曼谷由于海拔较低和排水基础设施不完善而容易发生洪水[32][33],这常常受到垃圾污染(尤其是塑料废物)的堵塞的影响[34]。现在,曼谷仰赖洪水防护堤坝和通过泵站和建设排水隧道来增加运河排水,但曼谷及其郊区的部分地区仍然经常被淹没。大雨导致城市径流超过排水系统和上游地区径流排放是主要的触发因素[35]。曼谷在1995年和2011年发生了严重洪水,影响了城市的大部分地区。2011年,曼谷的北部、东部和西部地区大部分地区被洪水淹没,有些地方持续了两个多月。

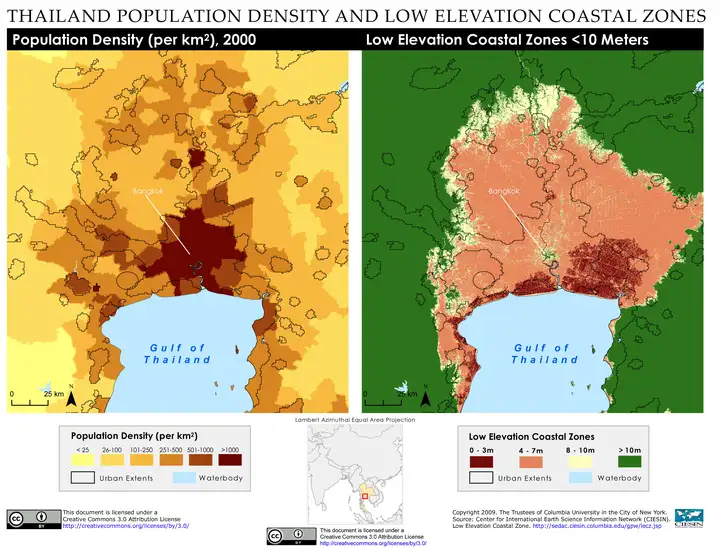

图片题注:Bangkok population density and low elevation coastal zones. Bangkok is especially vulnerable to sea level rise.

图片作者:SEDACMaps – 点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:曼谷人口密度和低海拔沿海地区。 曼谷特别容易受到海平面上升的影响。

Bangkok’s coastal location makes it particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels due to global warming and climate change. A study by the OECD has estimated that 5.138 million people in Bangkok may be exposed to coastal flooding by 2070, the seventh highest figure among the world’s port cities.[36]: 8 There are fears that the city may be submerged by 2030.[37][38][39] A study published in October 2019 in Nature Communications corrected earlier models of coastal elevations[40] and concluded that up to 12 million Thais—mostly in the greater Bangkok metropolitan area—face the prospect of annual flooding events.[41][42] This is compounded by coastal erosion, which is an issue in the gulf coastal area, a small length of which lies within Bangkok’s Bang Khun Thian District. Tidal flat ecosystems existed on the coast; however, many have been reclaimed for agriculture, aquaculture, and salt works.[43]

参考译文:曼谷作为沿海城市,由于全球变暖和气候变化导致海平面上升,特别容易受到威胁。经济合作与发展组织(OECD)的一项研究估计,到2070年,曼谷有513.8万人可能会受到沿海洪水的威胁,这在全球港口城市中排名第七[36]。有人担心到2030年曼谷可能会被淹没[37][38][39]。2019年10月发表在《自然通讯》杂志的一项研究纠正了早期的沿海高程模型,并得出结论,多达1200万泰国人面临每年洪水事件的可能性,其中大部分位于曼谷大都会区[41][42]。这还受到沿海侵蚀的影响,这是在泰国湾沿岸地区的一个问题,其中一小部分位于曼谷的Bang Khun Thian区。沿岸曾经存在潮滩生态系统;然而,许多地方已被用于农业、水产养殖和盐场的开垦[43]。

There are no mountains in Bangkok. The closest mountain range is the Khao Khiao Massif, about 40 km (25 mi) southeast of the city. Phu Khao Thong, the only hill in the metropolitan area, originated with a very large chedi that King Rama III (1787–1851) built at Wat Saket. The chedi collapsed during construction because the soft soil could not support its weight. Over the next few decades, the abandoned mud-and-brick structure acquired the shape of a natural hill and became overgrown with weeds. The locals called it phu khao (ภูเขา), as if it were a natural feature.[44] In the 1940s, enclosing concrete walls were added to stop the hill from eroding.[45]

参考译文:曼谷没有山脉。最近的山脉是距离曼谷东南约40公里(25英里)的Khao Khiao山脉。曼谷都会区内唯一的山是Phu Khao Thong,它起源于拉玛三世(1787-1851)在Wat Saket建造的一个非常大的佛塔。由于软土无法支撑其重量,这个佛塔在建造过程中倒塌了。在接下来的几十年里,这个被遗弃的泥砖结构逐渐成为一个自然的小山丘,并且长满了杂草。当地人称之为“phu khao”(ภูเขา),仿佛它是一个自然的地貌特征[44]。在上世纪40年代,人们添加了混凝土围墙来防止山体侵蚀[45]。

4.2 气候 | Climate

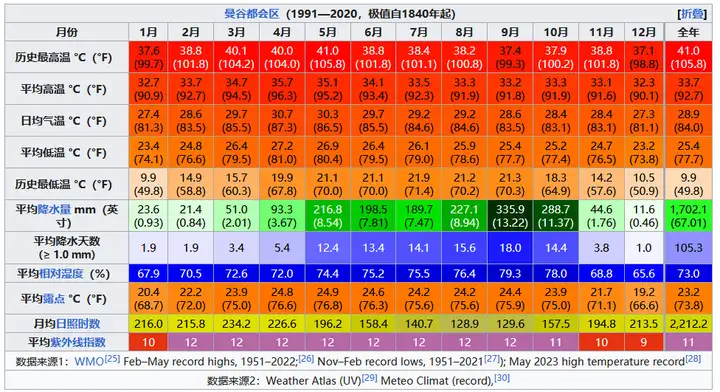

与泰国大部分地区一样,曼谷属于在柯本气候分类法下的热带莽原气候(Aw),受到南亚季风系统的影响。这座城市经常经历了三个天气:炎热、多雨和凉爽,尽管全年气温相当高,从12 月的平均低温22.0 °C (71.6 °F) 到平均高温 35.4 °C (95.7 °F) ) 在四月份。雨季从五月中旬左右西南季风的到来开始。九月则是最潮湿的月份,平均降雨量为 334.3毫米(13.16 英寸)。雨季持续到10月,干燥凉爽的东北季风持续到2月。

曼谷炎热的季节通常是干燥的状态,但偶尔也会出现夏季风暴。曼谷城市热岛的表面强度在白天测量为 2.5°C (4.5°F),晚上为 8.0°C (14°F)。 2013 年 3 月,曼谷大都市的最高记录温度为 40.1 °C (104.2 °F), 1955年 1 月记录的最低温度为 9.9 °C (49.8 °F)。 戈达德太空研究所的气候影响小组预测,气候变迁会对曼谷造成严重的天气影响。该研究所发现1960年的曼谷有193天达到或高于 32°C。2018年,曼谷的气温在32°C 或以上时预计为 276天。该组织预测,到2200年,温度在32°C 或以上时平均会增加297至344天。

4.3 行政区划 | Districts

主条目:曼谷县名列表

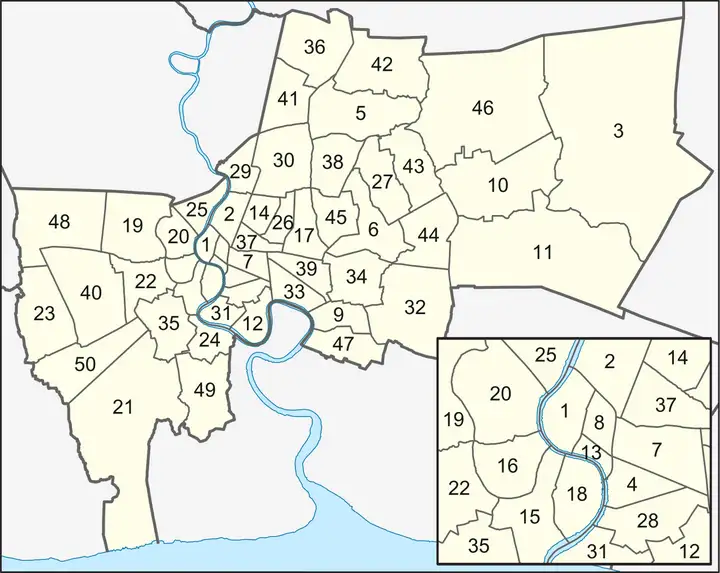

图片题注:显示曼谷50个县的地图 (标有分区的版本)

图片作者:Hdamm

曼谷的五十个县作为BMA授权下的行政区划。其中35个位于湄南河以东,15个位于西岸被称为城市的吞武里一侧。五十个县按编号排列为:[31][32]

- 拍那空县

- 律实县

- 廊卓县

- 挽叻县

- 挽卿县

- 挽甲必县

- 巴吞旺县

- 邦巴沙都拍县

- 拍昆仑县

- 民武里县

- 叻甲挽县

- 然那华县

- 三攀他旺县

- 披耶泰县

- 吞武里县

- 曼谷艾县

- 汇权县

- 空讪县

- 达铃灿县

- 曼谷莲县

- 挽坤天县

- 帕世乍能县

- 廊鉴县

- 拉布拉那县

- 挽拍县

- 邻铃县

- 汶昆县

- 沙吞县

- 挽赐县

- 乍都节县

- 挽柯莲县

- 巴威县

- 空堤县

- 萱銮县

- 宗通县

- 廊曼县

- 拉差贴威县

- 叻抛县

- 瓦他那县

- 挽奇县

- 朗四县

- 赛迈县

- 汉那尧县

- 沙攀松县

- 翁通郎县

- 空三华县

- 挽那县

- 他威瓦他那县

- 特库县

- 挽汶县

4.4 城市规划(城市景观) | Cityscape

曼谷各地的功能界别较不明晰,这可能是因宏观规划政策推进较晚导致。曼谷的都市规划最早追溯至1960年的利奇菲尔德计划(Litchfield Plan),但正式的分区规划法迟至1992年才全面实施。而在这期间,曼谷城区快速、自发而有机地发展扩大,体现为横向上沿着交通干道的带状发展,纵向上建成大量高层建筑和摩天大楼[33]。

The city has grown from its original centre along the river into a sprawling metropolis surrounded by swaths of suburban residential development extending north and south into neighbouring provinces. The highly populated and growing cities of Nonthaburi, Pak Kret, Rangsit and Samut Prakan are effectively now suburbs of Bangkok. Nevertheless, large agricultural areas remain within the city proper at its eastern and western fringes, and a small number of forest area is found within the city limits: 3,887 rai (6.2 km2; 2.4 sq mi), amounting to 0.4 per cent of city area.[57] Land use in the city consists of 23 per cent residential use, 24 per cent agriculture, and 30 per cent used for commerce, industry, and government.[1] The BMA’s City Planning Department (CPD) is responsible for planning and shaping further development. It published master plan updates in 1999 and 2006, and a third revision is undergoing public hearings in 2012.[58]

参考译文:这座城市从原本沿着河流的中心地带发展成了一个庞大的都市,周围是一片扩展到相邻省份的郊区住宅区。人口密集且不断增长的诺坦布里、帕克克雷特、朗西特和沙姆特巴康等城市实际上现在是曼谷的郊区。尽管如此,在城市的东部和西部边缘仍然有大片农业区域,并且在城市范围内还有少量的森林区域,面积为3,887莱(6.2平方公里;2.4平方英里),占城市面积的0.4%[57]。曼谷的土地利用包括23%的住宅用地、24%的农业用地和30%用于商业、工业和政府用途[1]。曼谷大都会区的城市规划部门负责规划和塑造进一步的发展。该部门在1999年和2006年发布了总体规划的更新,并且第三次修订目前正在进行公众听证会[58]。

图片题注:昭披耶河穿过曼谷市区

图片作者:Nik Cyclist from Bangkok, Thailand – 点击这里访问原图链接

曼谷的历史中心位于拉达那哥欣岛,属拍那空县[37],曼谷大皇宫和国柱庙是泰京曼谷建城之象征。拍那空县、邦巴沙都拍县,以及华裔聚居的三攀他旺县是曼谷的老城区[37]。19世纪早期,朱拉隆功王在北郊开辟律实宫,并修建拉差丹嫩路同旧皇宫相连,形成今日泰国政治重地律实县之基础[37]。

Many traditional neighbourhoods and markets are found here, including the Chinese settlement of Sampheng.[59] The city was expanded toward Dusit District in the early 19th century, following King Chulalongkorn’s relocation of the royal household to the new Dusit Palace. The buildings of the palace, including the neoclassical Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall, as well as the Royal Plaza and Ratchadamnoen Avenue which leads to it from the Grand Palace, reflect the heavy influence of European architecture at the time. Major government offices line the avenue, as does the Democracy Monument. The area is the site of the country’s seat of power as well as the city’s most popular tourist landmarks.[59]

参考译文:这里有许多传统的社区和市场,包括华人聚居地Sampheng[59]。19世纪早期,曼谷向Dusit区扩展,这是由于朱拉隆功国王将皇室迁往新的Dusit宫殿。宫殿建筑,包括新古典主义风格的阿南塔·萨玛科姆王座大厅,以及皇家广场和从大皇宫通向该广场的拉查达冠大道,反映了当时欧洲建筑的重要影响。大量政府办公楼位于这条大道上,同时还有min2 zhu3纪念碑。这个地区是该国的权力中心,也是该城市最受欢迎的旅游景点所在地[59]。

图片题注:The Royal Plaza in Dusit District was inspired by King Chulalongkorn’s visits to Europe.

图片作者:กสิณธร ราชโอรส

参考译文:律实县的皇家广场的设计灵感来自朱拉隆功国王访问欧洲的经历。

维基百科的图片说明:律实县五世王广场

曼谷的老城区鲜有高层建筑,与之形成对比的则是新兴的是隆路和沙吞路一带的商业区,属挽叻县和沙吞县,是泰国诸多大企业总部的所在地。朱拉隆功大学以北,是暹罗区和拉差巴颂区,建有数座大型商场,是曼谷乃至东南亚重要的购物中心。而沿着泰国3号公路素坤逸路,宛他那县和孔提县一带,分布着许多零售店铺和酒店,是曼谷另一处集中的娱乐区域,素坤逸路的支路和支巷则建有大量写字楼和高档住宅。曼谷并没有集中建成的中央商务区[38]。

Bangkok lacks a single distinct central business district. Instead, the areas of Siam and Ratchaprasong serve as a “central shopping district” containing many of the bigger malls and commercial areas in the city, as well as Siam Station, the only transfer point between the city’s two elevated train lines.[60] The Victory Monument in Ratchathewi District is among its most important road junctions, serving over 100 bus lines as well as an elevated train station. From the monument, Phahonyothin and Ratchawithi / Din Daeng Roads respectively run north and east linking to major residential areas. Most of the high-density development areas are within the 113-square-kilometre (44 sq mi) area encircled by the Ratchadaphisek inner ring road. Ratchadaphisek is lined with businesses and retail outlets, and office buildings also cluster around Ratchayothin Intersection in Chatuchak District to the north. Farther from the city centre, most areas are primarily mid- or low-density residential. The Thonburi side of the city is less developed, with fewer high rises. With the exception of a few secondary urban centres, Thonburi, in the same manner as the outlying eastern districts, consists mostly of residential and rural areas.

参考译文:曼谷缺乏一个明确的中央商业区。相反,Siam和Ratchaprasong地区被视为“中央购物区”,其中包括该城市许多大型商场和商业区,以及Siam站,是该城市两条高架铁路线之间唯一的换乘点[60]。拉达迪维区的胜利纪念碑是城市最重要的道路交汇处之一,有100多条公交线路和一个高架火车站。从纪念碑出发,Phahonyothin和Ratchawithi / Din Daeng Roads分别向北和东延伸,连接着主要的居住区。大部分高密度开发区位于由Ratchadaphisek环形路环绕的113平方公里(44平方英里)的区域内。Ratchadaphisek一带有各种企业和零售店,而办公楼则集中在Chatuchak区北部的Ratchayothin交叉口附近。离市中心较远的地区大多是中等或低密度住宅区。曼谷的东侧外围区域一样,曼谷的东侧外围区域主要由居住和农村地区组成,除了少数次要城市中心之外。与之相反,曼谷的东侧外围区域主要由居住和农村地区组成。

图片题注:素坤逸路周边建有大量高层建筑

图片作者:David McKelvey

拉差贴威县的胜利纪念碑一带是公共交通中心,从胜利纪念碑起始,拍凤裕庭路、叻猜威提路、邻铃路(Din Daeng Road)连通各大居民区。叻猜达披色路内环则是曼谷高密度开发区域的中心,其周边的113平方千米内商铺林立,向北的乍都节县拉差裕庭路口(Ratchayothin Intersection)一带亦是写字楼密集的地区。远郊处则主要是中密度或低密度住宅区。昭披耶河西岸的吞武里开发程度相对落后,主要是住宅区和乡村。

曼谷老城的许多街道两侧仍是传统的中葡式风格店屋。20世纪80年代起,许多高层建筑在各地拔地而起,形成风格冲突而迥异的城市景观[39]。城市的快速扩展的同时,亦产生不少贫民窟,2000年时,有100多万人居住在大约800个非正规住处内[40]。有些贫民区是棚户区,分布在空堤县等地[40]。

While most of Bangkok’s streets are fronted by vernacular shophouses, the largely unrestricted building euphoria of the 1980s has transformed the city into an urban area of skyscrapers and high rises of contrasting and clashing styles.[61] There are 581 skyscrapers over 90 metres (300 feet) tall in the city. Bangkok was ranked as the world’s eighth tallest city in 2016.[62] As a result of persistent economic disparity, many slums have emerged in the city. In 2000 there were over one million people living in about 800 informal settlements.[63] Some settlements are squatted such as the large slums in Khlong Toei District. In total there were 125 squatted areas.[63]

参考译文:尽管曼谷大部分街道都有地方特色的店屋,但上世纪80年代无限制的建筑热潮将这座城市变成了一个拥有各种截然不同风格的摩天大楼和高层建筑的城市[61]。曼谷有581座高度超过90米(300英尺)的摩天大楼。2016年,曼谷被评为世界第八高的城市[62]。由于持续存在的经济差距,该市出现了许多贫民窟。2000年,该市有超过100万人居住在约800个非正式定居点[63]。其中一些定居点是非法占用的,例如Khlong Toei区的大型贫民窟。总共有125个非法占地区[63]。

图片题注:Skyscrapers of Ratchadamri and Sukhumvit at night, viewed across Lumphini Park from the Si Lom – Sathon business district

图片作者:Benh LIEU SONG

参考译文:从 Si Lom – 沙吞商业区俯瞰是乐园对面的 Ratchadamri 和 Sukhumvit 摩天大楼

4.5 公园和绿地 | Parks and green zones

图片题注:Lumphini Park, an oasis amid the skyscrapers of Ratchadamri and Sukhumvit

图片作者:Terence Ong

参考译文:是乐园 (Lumphini Park),拉查丹利 (Ratchadamri) 和素坤逸 (Sukhumvit) 摩天大楼之间的一片绿洲

Bangkok has several parks, although these amount to a per capita total park area of only 1.82 square metres (19.6 sq ft) in the city proper. Total green space for the entire city is moderate, at 11.8 square metres (127 sq ft) per person. In the more densely built-up areas of the city these numbers are as low as 1.73 and 0.72 square metres (18.6 and 7.8 sq ft) per person.[64] More recent numbers claim that there is 3.3 square metres (36 sq ft) of green space per person,[65] compared to an average of 39 square metres (420 sq ft) in other cities across Asia. In Europe, London has 33.4 m2 of green space per head.[66] Bangkokians thus have 10 times less green space than is standard in the region’s urban areas.[67] Green belt areas include about 700 square kilometres (270 sq mi) of rice paddies and orchards on the eastern and western edges of the city, although their primary purpose is to serve as flood detention basins rather than to limit urban expansion.[68] Bang Kachao, a 20-square-kilometre (7.7 sq mi) conservation area on an oxbow of the Chao Phraya, lies just across the southern riverbank districts, in Samut Prakan province. A master development plan has been proposed to increase total park area to 4 square metres (43 sq ft) per person.[64]

参考译文:曼谷拥有几个公园,尽管在市区范围内,人均总公园面积仅为1.82平方米(19.6平方英尺)。整个城市的总绿地面积适中,每人占有11.8平方米(127平方英尺)。在城市更密集建设的地区,这些数字甚至低至每人1.73平方米和0.72平方米(分别为18.6平方英尺和7.8平方英尺)[64]。更近期的数据声称,每人拥有3.3平方米(36平方英尺)的绿地,而亚洲其他城市的平均值为39平方米(420平方英尺)。而伦敦在欧洲每人拥有33.4平方米的绿地[66]。因此,曼谷的居民在该地区的城市地区拥有的绿地面积是标准的十分之一[67]。绿化带区域包括位于城市东部和西部边缘的大约700平方公里(270平方英里)的稻田和果园,尽管它们的主要目的是作为洪水滞留池,而不是限制城市扩张[68]。曼谷南部河岸区的Samut Prakan省有一个位于湄南河上的20平方公里(7.7平方英里)的Bang Kachao保护区。已提出了一项总体规划,将总公园面积增加到每人4平方米(43平方英尺)[64]。

Bangkok’s largest parks include the centrally located Lumphini Park near the Silom–Sathon business district with an area of 57.6 hectares (142 acres), the 80-hectare (200-acre) Suanluang Rama IX in the east of the city, and the Chatuchak–Queen Sirikit–Wachirabenchathat park complex in northern Bangkok, which has a combined area of 92 hectares (230 acres).[69] More parks are expected to be created through the Green Bangkok 2030 project, which aims to leave the city with 10 square metres (110 sq ft) of green space per person, including 30% of the city having tree cover.[70]

参考译文:曼谷最大的公园包括位于市中心的兰空公园(Lumphini Park),面积为57.6公顷(142英亩),靠近Silom-Sathon商业区;位于城市东部的顺福拉玛九公园(Suanluang Rama IX),面积为80公顷(200英亩);以及位于曼谷北部的Chatuchak-Queen Sirikit-Wachirabenchathat公园综合体,总面积为92公顷(230英亩)[69]。通过“绿色曼谷2030”项目,预计将建立更多的公园,目标是每个人拥有10平方米(110平方英尺)的绿地,其中包括城市的30%有树木覆盖率[70]。

5. 人口统计 | Demography

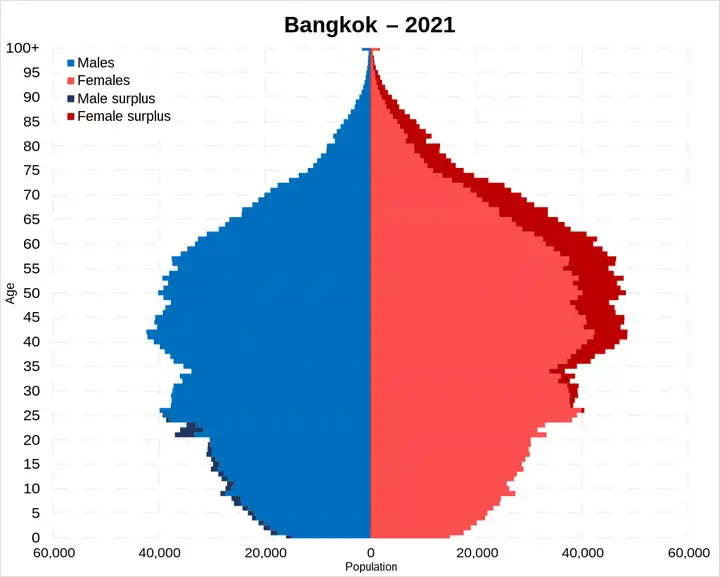

图片题注:Bangkok population pyramid, based on 2021 population registry

图片作者:Tweedle

参考译文:曼谷人口金字塔,基于 2021 年人口登记

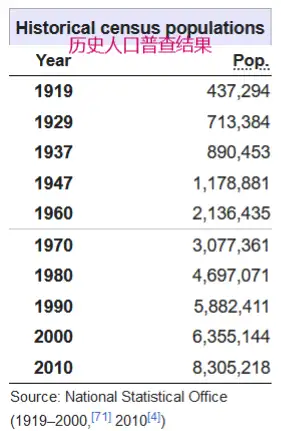

The city of Bangkok has a population of 8,305,218 according to the 2010 census, or 12.6 per cent of the national population,[4] while 2020 estimates place the figure at 10.539 million (15.3 per cent).[5] Roughly half are internal migrants from other Thai provinces;[72] population registry statistics recorded 5,676,648 residents belonging to 2,959,524 households in 2018.[73][i] Much of Bangkok’s daytime population commutes from surrounding provinces in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region, the total population of which is 14,626,225 (2010 census).[4] Bangkok is a cosmopolitan city; the census showed that it is home to 567,120 expatriates from Asian countries (including 71,024 Chinese and 63,069 Japanese nationals), 88,177 from Europe, 32,241 from the Americas, 5,856 from Oceania and 5,758 from Africa. Migrants from neighbouring countries include 216,528 Burmese, 72,934 Cambodians and 52,498 Lao.[74] In 2018, numbers show that there are 370,000 international migrants registered with the Department of Employment, more than half of them migrants from Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.[72]

参考译文:根据2010年的人口普查,曼谷市的人口为8,305,218人,占全国人口的12.6%[4],而2020年的估计人口为10,539,000人,占全国人口的15.3%[5]。大约一半的人口来自泰国其他省份的内部移民[72],根据人口登记统计,2018年有5,676,648名居民属于2,959,524个家庭[73][i]。曼谷的白天人口大部分来自曼谷大都会地区周边的省份,该地区的总人口为14,626,225人(2010年普查数据)[4]。曼谷是一个国际化的城市;人口普查显示,曼谷有567,120名来自亚洲国家的外籍人士(包括71,024名中国人和63,069名日本人),88,177名来自欧洲,32,241名来自美洲,5,856名来自大洋洲和5,758名来自非洲。邻国的移民包括216,528名缅甸人,72,934名柬埔寨人和52,498名老挝人[74]。2018年的数据显示,有370,000名国际移民在就业部门注册,其中超过一半来自柬埔寨、老挝和缅甸[72]。

Following its establishment as capital city in 1782, Bangkok grew only slightly throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. British diplomat John Crawfurd, visiting in 1822, estimated its population at no more than 50,000.[75] As a result of Western medicine brought by missionaries as well as increased immigration from both within Siam and overseas, Bangkok’s population gradually increased as the city modernized in the late 19th century. This growth became even more pronounced in the 1930s, following the discovery of antibiotics. Although family planning and birth control were introduced in the 1960s, the lowered birth rate was more than offset by increased migration from the provinces as economic expansion accelerated. Only in the 1990s have Bangkok’s population growth rates decreased, following the national rate. Thailand had long since become highly centralized around the capital. In 1980, Bangkok’s population was fifty-one times that of Hat Yai and Songkhla, the second-largest urban centre at the time, making it the world’s most prominent primate city.[76][77]

参考译文:在1782年成为首都后,曼谷在18世纪和19世纪初期的增长非常缓慢。英国外交官约翰·克劳福德于1822年访问时估计其人口不超过5万人[75]。随着西方传教士带来的医学知识以及来自暹罗国内外的增加移民,曼谷的人口在19世纪末的城市现代化进程中逐渐增加。随着1930年代发现抗生素,这种增长变得更加明显。尽管计划生育和避孕在1960年代引入,但由于经济扩张加速,来自省份的移民增加,降低的出生率被抵消了。直到1990年代,曼谷的人口增长率才开始下降,跟随全国趋势。泰国早已高度集中在首都周围。1980年,曼谷的人口是当时第二大城市合艾和宋卡府的51倍,使其成为世界上最重要的主要城市[76][77]。

图片题注:Yaowarat Road, the centre of Bangkok’s Chinatown. Chinese immigrants historically formed the majority of the city’s population.

图片作者:Ninara from Helsinki, Finland

参考译文:耀华力路,曼谷唐人街的中心。 历史上,中国移民占该市人口的大多数。

The majority of Bangkok’s population identify as Thai,[j] although details on the city’s ethnic make-up are unavailable, as the national census does not document race.[k] Bangkok’s cultural pluralism dates back to the early days of its founding: several ethnic communities were formed by immigrants and forced settlers including the Khmer, northern Thai, Lao, Vietnamese, Mon and Malay.[10] Most prominent were the Chinese, who played major roles in the city’s trade and became the majority of Bangkok’s population—estimates include up to three-fourths in 1828 and almost half in the 1950s.[81][l] Chinese immigration was restricted from the 1930s and effectively ceased after the Chinese Revolution in 1949. Their prominence subsequently declined as younger generations of Thai Chinese integrated and adopted a Thai identity. Bangkok is still nevertheless home to a large Chinese community, with the greatest concentration in Yaowarat, Bangkok’s Chinatown.

参考译文:曼谷的大部分人口自认为是泰族,尽管关于该城市的族裔构成的详细信息不可得知,因为国家人口普查并未记录种族[10]。曼谷的文化多元化可以追溯到其建城初期:许多移民和被迫定居者形成了几个不同的民族社群,包括高棉族、北部泰族、老挝族、越南族、蒙族和马来族[10]。其中最突出的是华人,他们在曼谷的贸易中扮演着重要角色,并成为曼谷人口的大多数人口—据估计,1828年达到四分之三,到1950年代接近一半[81]。20世纪30年代开始限制华人移民,并在1949年的中国ge2 ming4后实际停止。随后,随着年轻一代的泰籍华人融入和接受了泰国的身份认同,他们的地位逐渐下降。尽管如此,曼谷仍然是一个庞大的华人社区的所在地,其中最集中的地方是曼谷的唐人街——泰语称为Yaowarat。

曼谷亦有众多海外侨民社区。拍乎叻路是曼谷的小印度,而在素坤逸路两侧,分布有日本社区、阿拉伯和北非社区及韩国社区。许多当代中国大陆移民居住在有“代购街”之称的汇权县一带[19]。

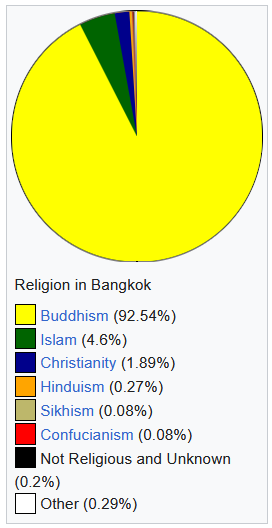

The majority (93 per cent) of the city’s population is Buddhist, according to the 2010 census. Other religions include Islam (4.6 per cent), Christianity (1.9 per cent), Hinduism (0.3 per cent), Sikhism (0.1 per cent) and Confucianism (0.1 per cent).[83]

参考译文:根据2010年的人口普查数据,曼谷市的大多数人口(93%)信奉佛教。其他宗教包括伊斯兰教(4.6%)、基督教(1.9%)、印度教(0.3%)、锡克教(0.1%)和儒教(0.1%)[83]。

犹太教徒约300人,0.3%信奉印度教。曼谷约有400座佛教寺,55座清真寺,10座教堂,2间犹太会堂[20]。

Apart from Yaowarat, Bangkok also has several other distinct ethnic neighbourhoods. The Indian community is centred in Phahurat, where the Gurdwara Siri Guru Singh Sabha, founded in 1933, is located. Ban Khrua on Saen Saep Canal is home to descendants of the Cham who settled in the late 18th century. Although the Portuguese who settled during the Thonburi period have ceased to exist as a distinct community, their past is reflected in Santa Cruz Church, on the west bank of the river. Likewise, Assumption Cathedral on Charoen Krung Road is among many European-style buildings in the Old Farang Quarter, where European diplomats and merchants lived in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Nearby, the Haroon Mosque is the centre of a Muslim community. Newer expatriate communities exist along Sukhumvit Road, including the Japanese community near Soi Phrom Phong and Soi Thong Lo, and the Arab and North African neighbourhood along Soi Nana. Sukhumvit Plaza, a mall on Soi Sukhumvit 12, is popularly known as Korea Town.

参考译文:除了唐人街,曼谷还有几个其他独特的民族社区。印度社区集中在帕哈拉区,那里有一座成立于1933年的古尔达瓦拉·西里古鲁·辛格·萨巴寺庙。位于沙恩色普运河的Bang Khrua是18世纪后期定居的占族后裔的家园。尽管在东巴里(Thonburi)时期定居的葡萄牙人已经不存在作为一个独特的社群,但他们的历史在河的西岸的圣十字教堂中得到了体现。同样,在Charoen Krung Road上的圣母升天主教堂是老远洋区域内许多欧式建筑中的一座,19世纪末至20世纪初,欧洲外交官和商人曾在这里居住。附近的哈伦清真寺是一个穆斯林社区的中心。沿着素坤逸路(Sukhumvit Road)还有一些较新的外籍社区,包括靠近Phrom Phong街和Thong Lo街的日本社区,以及沿着Nana街的阿拉伯和北非社区。素坤逸广场(Sukhumvit Plaza)是位于素坤逸12巷的购物中心,也被广泛称为韩国城。

语言

曼谷曾经是潮阳话地区为主,[21]二战后,政府强迫同化当地华裔潮州人,故语言转移到泰语速度很快。 [22]今日曼谷主要语言有三种,泰语、老挝语(依善语)和缅甸语,泰语是现代当地最普遍的语言,但当地方言跟暹罗人的泰语有差异。曼谷的老挝语用泰文书写,是依善地区的人暂时工作的语言,但泰语母语者有某种程度相互理解性。缅甸语是缅籍劳工使用的语言。英语跟中文仅在旅游景点有部分使用。[23]

6. 经济 | Economy

图片作者:Ninara from Helsinki, Finland

曼谷是泰国经济中心。2018年,曼谷全市经济总产值为5.384万亿泰铢(1740亿美元),人均产值604,521泰铢(19,500美元),是泰国全国平均水平的两倍多。曼谷都会区的总产值为7.667万亿泰铢(2470亿美元)[41]。

批发和零售贸易是该市经济中最大的部门,占曼谷省生产总值的24%。其次是制造业(14.3%);房地产、租赁和商业活动(12.4%)、运输和通讯(11.6%)、金融中介(11.1%)。仅曼谷就占泰国服务业的48.4%,而后者又占泰国GDP的49%。以曼谷都会区统计,制造业是该地经济发展起最重要作用,占区域生产总值的28.2%,反映曼谷邻近府分的工业发展密度[42]。曼谷都会区是东南亚最大的汽车生产中心[43]。旅游业也是曼谷经济的重要部门,2010年创造了4275亿泰铢(133.8 亿美元)的收入,为重要的经济支柱[44]。

图片题注:MahaNakhon, the city’s tallest building from 2016 to 2018, stands among the skyscrapers of Sathon Road, one of Bangkok’s main financial districts.

图片作者:Ninara from Helsinki, Finland

参考译文:MahaNakhon 是 2016 年至 2018 年曼谷最高的建筑,矗立在曼谷主要金融区之一沙吞路的摩天大楼之中。

泰国证券交易所(SET)位于曼谷叻察达披色路,总市值约为4900亿美元(2017年8月31日)。当代,曼谷已经成为东南亚的重要经济支柱,股市市值仅次于新加坡,排名第二。全球化及世界城市研究网络(GaWC)将曼谷列为“Alpha-”级别的国际都市,在Z/Yen的全球金融中心指数中排名第59位[45][46]。

曼谷是泰国所有主要商业银行和金融机构以及该国大公司的总部所在地。由于相对于其他亚洲主要商业中心的劳动力和运营成本较低,许多跨国公司将其区域总部设在曼谷。福布斯全球企业2000强中有17家泰国企业上榜,其总部皆位于曼谷,其中就包括泰国唯一的财富世界500强公司泰国国家石油股份[47][48]。

图片题注:暹罗区是东南亚的购物中心之一

图片作者:Paolobon140

收入不平等是曼谷的一个主要问题,特别是在来自农村省份和邻国相对低收入移民与,中产阶级专业人士和商业精英之间的差异相当明显。尽管绝对贫困率很低,但在2010年曼谷的登记居民中有0.64%生活在贫困线以下,而全国平均水平为7.75%——经济差距仍然很大[49]。该市的基尼系数为0.48,表明人均收入的为高度不平等状态[50]。

7. 旅游 | Tourism

Main article: Tourism in Bangkok(主条目:曼谷旅游)

图片作者:Nawit science

图片题注:The Giant Swing

图片作者:IPhi044

曼谷是世界顶级旅游目的地之一,观光业是占泰国国民总收入12%的重要外汇来源,在全球162个城市中,万事达在其2018年全球目的地城市指数中将曼谷列为国际游客人数最多的目的地城市,领先于伦敦,2017年过夜游客超过2000万[51]。Euromonitor International 在2016年最佳城市目的地排名中将曼谷排在第四位[52]。从2010年到2013年,曼谷连续四年被Travel + Leisure杂志的读者调查评为世界最佳城市[53]。

曼谷是泰国的门户,大多数赴泰旅游的外国游客都会前往曼谷。对于泰国本国人来说,曼谷同样是旅游胜地。2010年,泰国旅游部录得26,861,095名泰国游客和11,361,808名外国游客到曼谷旅游,为15,031,244名客人提供住宿,占该市86,687间酒店客房的49.9%[44]。曼谷在2017年的排名中也位居全球最受欢迎的旅游目的地之首[54][55][56][57]。

曼谷多姿多彩的风光、名胜和城市生活吸引著不同的游客群体。王宫、寺庙以及博物馆是其主要的历史文化景点,其中最有名的是大皇宫内的玉佛寺和在其河斜对面的黎明寺。购物和餐饮体验选择广泛,丰俭由人。这座城市还以其充满活力的夜生活而闻名。尽管曼谷的性旅游场景为外国人所熟知,但通常不会被当地人或政府公开承认。

图片题注:Wat Phra Kaew in the Grand Palace is among Bangkok’s major tourist attractions.

图片作者:Anindya Indira Putri

参考译文:大皇宫的玉佛寺是曼谷的主要旅游景点之一。

曼谷著名的景点包括大皇宫和主要的佛教寺庙,包括玉佛寺、卧佛寺和郑王庙,大秋千和伊拉旺神坛展现了婆罗门教对泰国文化的影响,汤普生博物馆则是泰国传统建筑的典范。博物馆包括曼谷国家博物馆、皇家驳船国家博物馆、暹罗博物馆等。湄南河和吞武里运河上的游轮之旅可以欣赏到这座城市的一些传统建筑和水上生活方式[58]。

Shopping venues, many of which are popular with both tourists and locals, range from the shopping centres and department stores concentrated in Siam and Ratchaprasong to the sprawling Chatuchak Weekend Market. Taling Chan Floating Market is among the few such markets in Bangkok. Yaowarat is known for its shops as well as street-side food stalls and restaurants, which are also found throughout the city. Khao San Road has long been famous as a destination for backpacker tourism, with its budget accommodation, shops and bars attracting visitors from all over the world.

图片题注:Khao San Road is lined by budget accommodation, shops and bars catering to tourists.

图片作者:Marcin Konsek

参考译文:考山路两旁遍布经济型住宿、商店和迎合游客需求的酒吧。

图片题注:考山路

图片作者:Rmunsvila

从暹罗区和拉差巴颂的购物中心和百货公司,到广阔的乍都节市场,曼谷许多购物场所深受游客和当地人的欢迎。曼谷的水上市场为数不多,仅余下远郊的大林江水上市场等。街头小吃摊遍布曼谷各大闹市区,其中以耀华力一带最为闻名。考山路长期以来则一直作为背包客旅游的目的地而闻名,其廉价住宿、商店和酒吧吸引著来自世界各地的游客。

Bangkok has a reputation overseas as a major destination in the sex industry. Although prostitution is technically illegal and is rarely openly discussed in Thailand, it commonly takes place among massage parlours, saunas and hourly hotels, serving foreign tourists as well as locals. Bangkok has acquired the nickname “Sin City of Asia” for its level of sex tourism.[105]

参考译文:曼谷在海外有一个作为性产业主要目的地的声誉。虽然卖yin2在泰国在法律上是非法的,并且很少在公开场合讨论,但它通常在按摩院、桑拿和钟点酒店中普遍存在,为外国游客和当地人提供服务。曼谷因其性旅游业而被冠以“亚洲的罪恶之城”的绰号。

诈骗、过度收费和双重定价则是外国游客经常遇到的问题。在一项针对616名泰国游客的调查中,7.79%的人表示遇到了诈骗,其中最常见的是宝石诈骗,游客被诱骗购买价格过高的珠宝[60]。

图片题注:湄南河和曼谷文华东方酒店

图片作者:Preecha.MJ

8. 文化 | Culture

图片题注:Temporary art display at Siam Discovery during the Bangkok Art Biennale 2018

图片作者:Chainwit.

参考译文:2018 年曼谷艺术双年展期间暹罗探索中心的临时艺术展览

曼谷的文化反映了其作为泰国的财富和现代化中心的地位。长久以来,曼谷一直是西方的概念和物质商品的进入门户,已经被其居民在不同程度上采用并与泰国的价值观相融合。这在不断扩大的中产阶级的生活方式中最为明显。因此炫耀性消费是经济和社会地位的体现,购物中心是市民周末的热门去处,同时手机等电子产品和消费产品的所有权无处不在。这伴随着一定程度的世俗主义,因为宗教在日常生活中的作用已经相当减弱,尽管这种趋势已经蔓延到其他城市中心,在一定程度上也蔓延到农村,但曼谷仍然处于社会变革的前沿线。

曼谷的一个显著的特色就是随处可见的街头小贩会出售从食品到服装和配饰的各种商品。据估计,曼各一共有超过十万名小贩。虽然BMA已经授权在287个站点进行这种做法,但在另外的407个站点的大部分小贩活动都是非法进行的。小贩经常占用了城市的行人道空间并阻塞行人交通,但曼谷的许多居民还是要依靠这些小贩来吃饭,而BMA控制小贩数量的努力基本上没有成功。

然而,在2015年,BMA在国家和平与秩序委员会(泰国执政的军政府)的支持下,开始打击街头小贩以收回公共空间。许多著名的市场社区受到影响,包括空统县、萨潘莱克和巴空塔拉特的花卉市场。2016年,近15,000名供应商被赶出39个公共区域。虽然一些人对关注行人权利的努力表示赞赏,但其他人表示担心高档化会导致城市特色的丧失和人们生活方式的不利变化。

8.1 节日和活动 | Festivals and events

图片题注:拉差丹侬大道每年都会用灯光装饰大道,以庆祝泰国国王的生日

图片作者:Lerdsuwa

曼谷的居民经常庆祝泰国的许多传统年度节日。在4月13日至15日的泼水节期间,整个曼谷都会举行传统的仪式和打水仗的活动。水灯节通常在11月举行,新年庆祝活动在许多场所举行,最引人注目的是位于中央世界商业中心广场的活动,此外与王室有关的纪念活动也主要在曼谷举行,包括10月23日的拉玛五世阵亡将士纪念日,民众经常会前往皇家广场的拉玛五世马术雕像前献上花圈。现在的国王和王后的生日分别在12月5日和8月12日,被视为泰国的国家父亲节和国家母亲节,这些国定假日在前夕由皇室、观众双方共同庆祝,并由国王或王后发表演讲,在纪念日举行公众集会。国王的生日也以皇家卫队的you2 xing2为标志。此外,位于曼谷的华人社区也会庆祝关于农历新年(1月至2月)和素食节(9月至10月)的活动。

皇家田广场是泰国举办风筝、体育和音乐节的举办地,通常在3月举行,皇家耕地仪式则在5月举行。4月初的红十字会在Suan Amporn公园和皇家广场举行,设有众多摊位,提供商品、游戏和展品。[61]

The Chinese New Year (January–February) and Vegetarian Festival (September–October) are celebrated widely by the Chinese community, especially in Yaowarat.[112]

参考译文:华人社区广泛庆祝中国新年(一月至二月)和素斋节(九月至十月),尤其在中国城(Yaowarat)举行庆祝活动。

2013年,曼谷被联合国教科文组织指定为世界图书之都。[62] 曼谷的第一届泰国国际同志骄傲节于1999年10月31日举行[63] 。第一次官方游行则于 2022年首度举行,被宣布为2022年曼谷“12个月度节日”的一部分。[64]

图片题注:湄南河和挽叻县

图片作者:Nik Cyclist from Bangkok, Thailand – 点击这里访问原图链接

8.2 媒体 | Media

Bangkok is the centre of Thailand’s media industry. All national newspapers, broadcast media and major publishers are based in the capital. Its 21 national newspapers had a combined daily circulation of about two million in 2002. These include the mass-oriented Thai Rath, Khao Sod and Daily News, the first of which currently prints a million copies per day,[116] as well as the less sensational Matichon and Krungthep Thurakij. The Bangkok Post and The Nation are the two national English language dailies. Foreign publications including The Asian Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, The Straits Times and the Yomiuri Shimbun also have operations in Bangkok.[117] The large majority of Thailand’s more than 200 magazines are published in the capital, and include news magazines as well as lifestyle, entertainment, gossip and fashion-related publications.

参考译文:曼谷是泰国媒体业的中心。所有国家报纸、广播媒体和主要出版商都设在首都。2002年,泰国的21家国家报纸每天的总发行量约为200万份。其中包括面向大众的《泰日报》(Thai Rath)、《Khao Sod》和《每日新闻》(Daily News),《泰日报》目前每天印刷一百万份[116],以及较少轰动的《Matichon》和《Krungthep Thurakij》。《曼谷邮报》(Bangkok Post)和《国家报》(The Nation)是泰国两家全国性的英文日报。外国刊物,包括《亚洲华尔街日报》(The Asian Wall Street Journal)、《金融时报》(Financial Times)、《海峡时报》(The Straits Times)和《读卖新闻》(Yomiuri Shimbun)也在曼谷设有业务[117]。泰国200多种杂志中的绝大多数在首都出版,并包括新闻杂志以及生活方式、娱乐、八卦和时尚相关的出版物。

Bangkok is also the hub of Thailand’s broadcast television. All six national terrestrial channels, Channels 3, 5 and 7, Modernine, NBT and Thai PBS, have headquarters and main studios in the capital. GMM Grammy is Thailand’s largest mass-media conglomerate is also headquartered in Bangkok as well. With the exception of local news segments broadcast by the NBT, all programming is done in Bangkok and repeated throughout the provinces. However, this centralised model is weakening with the rise of cable television, which has many local providers. There are numerous cable and satellite channels based in Bangkok. TrueVisions is the major subscription television provider in Bangkok and Thailand, and it also carries international programming. Bangkok was home to 40 of Thailand’s 311 FM radio stations and 38 of its 212 AM stations in 2002.[117] Broadcast media reform stipulated by the 1997 constitution has been progressing slowly, although many community radio stations have emerged in the city.

参考译文:曼谷也是泰国广播电视的中心。泰国的六个全国地面频道,3台、5台和7台、Modernine、NBT和泰国公共电视台(Thai PBS)的总部和主要工作室都设在曼谷。泰国最大的大众媒体集团GMM Grammy总部也设在曼谷。除了NBT播放的当地新闻片段外,所有节目都在曼谷制作,并在全国各地重播。然而,随着有线电视的崛起,这种集中模式正在削弱,许多地方提供商提供有线电视服务。曼谷有众多基于有线和卫星的频道。TrueVisions是曼谷和泰国的主要付费电视服务提供商,也提供国际节目。2002年,曼谷拥有泰国311个调频广播电台中的40个以及其212个调幅广播电台中的38个[117]。1997年宪法规定的广播媒体改革进展缓慢,尽管许多社区广播电台在该市兴起。

图片题注:湄南河和四季河岸公寓

图片作者:Ninara from Helsinki, Finland – 点击这里访问原图链接

Likewise, Bangkok has dominated the Thai film industry since its inception. Although film settings normally feature locations throughout the country, the city is home to all major film studios in Thailand such as GDH 559 (GMM Grammy’s film production subsidiary), Sahamongkol Film International and Five Star Production. Bangkok has dozens of cinemas and multiplexes, and the city hosts two major film festivals annually, the Bangkok International Film Festival and the World Film Festival of Bangkok.

参考译文:自成立以来,曼谷一直主导着泰国的电影产业。虽然电影的场景通常包括全国各地的地点,但曼谷是泰国所有主要电影工作室的所在地,如GMM Grammy的电影制作子公司GDH 559、Sahamongkol Film International和Five Star Production。曼谷有数十家电影院和多功能影院,每年举办两个重要的电影节,分别是曼谷国际电影节和曼谷世界电影节。

8.3 艺术 | Art

图片题注:The Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, the city’s major public contemporary art venue, was opened in 2008 after many delays.

图片作者:Supanut Arunoprayote.

参考译文:曼谷艺术文化中心是该市主要的公共当代艺术场馆,在多次推迟后于 2008 年开业。

Traditional Thai art, long developed within religious and royal contexts, continues to be sponsored by various government agencies in Bangkok, including the Department of Fine Arts‘ Office of Traditional Arts. The SUPPORT Foundation in Chitralada Palace sponsors traditional and folk handicrafts. Various communities throughout the city still practice their traditional crafts, including the production of khon masks, alms bowls, and classical musical instruments. The National Gallery hosts permanent collection of traditional and modern art, with temporary contemporary exhibits. Bangkok’s contemporary art scene has slowly grown from relative obscurity into the public sphere over the past two decades. Private galleries gradually emerged to provide exposure for new artists, including the Patravadi Theatre and H Gallery. The centrally located Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, opened in 2008 following a fifteen-year lobbying campaign, is now the largest public exhibition space in the city.[118] There are also many other art galleries and museums, including the privately owned Museum of Contemporary Art.

参考译文:传统泰国艺术长期以来一直在宗教和皇家背景下发展,目前仍由曼谷各个政府机构赞助,包括美术部的传统艺术办公室。位于吉特拉拉达宫的SUPPORT基金会赞助传统和民间手工艺品。城市中的各个社区仍然保留着他们的传统工艺,包括khon面具、施舍碗和古典乐器的制作。国家美术馆拥有传统和现代艺术的永久收藏,还定期展出当代艺术作品。在过去的二十年里,曼谷的当代艺术场景从相对默默无闻逐渐走向公众视野。私人画廊逐渐涌现,为新艺术家提供机会展示,其中包括Patravadi剧院和H画廊。位于市中心的曼谷艺术文化中心于2008年开放,经过15年的游说运动,现在成为该市最大的公共展览空间[118]。还有许多其他艺术画廊和博物馆,包括私人拥有的当代艺术博物馆。

The city’s performing arts scene features traditional theatre and dance as well as Western-style plays. Khon and other traditional dances are regularly performed at the National Theatre and Salachalermkrung Royal Theatre, while the Thailand Cultural Centre is a newer multi-purpose venue which also hosts musicals, orchestras and other events. Numerous venues regularly feature a variety of performances throughout the city.

参考译文:曼谷的表演艺术场景包括传统戏剧和舞蹈,以及西式话剧。Khon和其他传统舞蹈定期在国家剧院和Salachalermkrung皇家剧院上演,而泰国文化中心是一个较新的多功能场所,也举办音乐剧、管弦乐团和其他活动。城市中有许多场馆定期举办各种演出。

9. 体育 | Sport

图片题注:Rajamangala Stadium was built for the 1998 Asian Games and Thailand national football team home stadium.

图片作者:Christian Bellgardt

参考译文:拉加曼加拉体育场是为1998年亚运会和泰国国家足球队的主场而建的。

As is the national trend, association football and Muay Thai dominate Bangkok’s spectator sport scene.[119] Muangthong United, Bangkok United, BG Pathum United, Port and Police Tero are major Thai League clubs based in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region,[120][121] while the Rajadamnern and Lumpini stadiums are the main kickboxing venues.

参考译文:与全国趋势一样,足球和泰拳在曼谷的观赛体育场景中占据主导地位。Muangthong United、Bangkok United、BG Pathum United、Port和Police Tero是总部位于曼谷都会区的主要泰国职业联赛俱乐部,而拉贾达曼恩和隆平尼体育场则是主要的泰拳比赛场馆。

While sepak takraw can be seen played in open spaces throughout the city, football and other modern sports are now the norm. Western sports introduced during the reign of King Chulalongkorn were originally only available to the privileged, and such status is still associated with certain sports. Golf is popular among the upwardly mobile, and there are several courses in Bangkok. Horse racing, highly popular at the mid-20th century, still takes place at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club.

参考译文:在曼谷各个开放空间可以看到人们打踢踏球,但足球和其他现代运动现在已成为常态。在拉玛五世统治时期引进的西方体育起初只对特权阶层开放,而与某些体育项目仍然有特定的社会地位相关联。高尔夫球在上升中的中产阶级中很受欢迎,在曼谷有几个高尔夫球场。赛马在20世纪中叶非常受欢迎,目前仍在皇家曼谷体育俱乐部举行。

There are many public sporting facilities located throughout Bangkok. The two main centres are the National Stadium complex, which dates to 1938, and the newer Hua Mak Sports Complex, which was built for the 1998 Asian Games. Bangkok had also hosted the games in 1966, 1970 and 1978; the most of any city. The city was the host of the inaugural Southeast Asian Games in 1959, the 2007 Summer Universiade and the 2012 FIFA Futsal World Cup.

参考译文:曼谷有许多公共体育设施。其中两个主要中心是建于1938年的国家体育场综合体和为1998年亚洲运动会建造的新的华玛克体育综合体。曼谷还分别在1966年、1970年和1978年举办了东南亚运动会,是所有城市中举办次数最多的。曼谷还是1959年首届东南亚运动会、2007年夏季世界大学生运动会和2012年国际足球联合会五人制世界杯的主办城市。

10. 交通 | Transport

Main article: Transport in Bangkok(主条目:曼谷交通)

维基百科的官方提示:This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources:“Bangkok” – news·newspapers·books·scholar·JSTOR(April 2021) (template removal help)

参考译文:这一部分需要额外的引用来验证。请通过在这一部分添加可靠来源的引用来帮助改进这篇文章。未经来源证实的材料可能会受到质疑和删除。寻找来源:“曼谷” – 新闻·报纸·书籍·学者·JSTOR(2021年4月)(模板移除帮助)

图片题注:Streetlamps and headlights illuminate the Makkasan Interchange of the expressway. The system sees a traffic of over 1.5 million vehicles per day.[122]

图片作者:aotaro from Yokohama, Japan – 点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:路灯和车头灯照亮了高速公路的 Makkasan 立交桥。 该系统每天的交通流量超过 150 万辆。[122]

Although Bangkok’s canals historically served as a major mode of transport, they have long since been surpassed in importance by land traffic. Charoen Krung Road, the first to be built by Western techniques, was completed in 1864. Since then, the road network has vastly expanded to accommodate the sprawling city. A complex elevated expressway network and Don Mueang Tollway helps bring traffic into and out of the city centre, but Bangkok’s rapid growth has put a large strain on infrastructure, and traffic jams have plagued the city since the 1990s. Although rail transport was introduced in 1893 and trams served the city from 1888 to 1968, it was only in 1999 that Bangkok’s first rapid transit system began operation. Older public transport systems include an extensive bus network and boat services which still operate on the Chao Phraya and two canals. Taxis appear in the form of cars, motorcycles, and “tuk-tuk” auto rickshaws.

参考译文:尽管曼谷的运河在历史上曾是主要的交通方式,但由于陆地交通的重要性已经超过了它们。曼谷的第一条由西方技术建造的道路——Charoen Krung Road在1864年竣工。自那以后,道路网络已经大大扩展,以适应这座庞大城市的需求。一个复杂的高架高速公路网络和东门高速公路帮助将交通引入和离开市中心,但曼谷的快速增长对基础设施造成了很大压力,交通拥堵问题自20世纪90年代以来一直困扰着这座城市。虽然铁路交通始于1893年,电车于1888年至1968年间为城市提供服务,但直到1999年,曼谷的第一个快速交通系统才开始运营。较旧的公共交通系统包括广泛的巴士网络和仍然在湄南河和两个运河上运营的船舶服务。出租车以汽车、摩托车和“嘟嘟车”三轮摩托车的形式出现。

Bangkok is connected to the rest of the country through the national highway and rail networks, as well as by domestic flights to and from the city’s two international airports (Suvarnabhumi and Don Mueang). Its centuries-old maritime transport of goods is still conducted through Khlong Toei Port.

参考译文:曼谷通过国家公路和铁路网络与全国其他地区相连,同时通过往返于该市的两个国际机场(素万那普和廊曼)的国内航班也与其他地区连接。曼谷数百年来的海上货物运输仍通过曼谷港(Khlong Toei Port)进行。

The BMA is largely responsible for overseeing the construction and maintenance of the road network and transport systems through its Public Works Department and Traffic and Transportation Department. However, many separate government agencies are also in charge of the individual systems, and much of transport-related policy planning and funding is contributed to by the national government.

参考译文:曼谷都市管理局(BMA)主要负责通过其公共工程部门和交通运输部门监督道路网络和交通系统的建设和维护。然而,许多独立的政府机构也负责各个系统,国家政府也为交通相关的政策规划和资金提供了很大的支持。

10.1 道路 | Roads

图片题注:Traffic jams, seen here on Sukhumvit Road, are common in Bangkok.

图片作者:Chainwit.

参考译文:素坤逸路上的交通堵塞在曼谷很常见。

曼谷由于道路容量无法应付汽车成长数量,因此交通堵塞十分严重。绕行曼谷的东西环道早已建成,确实能节省驾车者不少时间。但除非半夜三更开车上环道,否则仍难以躲避车流的高峰。

Road-based transport is the primary mode of travel in Bangkok. Due to the city’s organic development, its streets do not follow an organized grid structure. Forty-eight major roads link the different areas of the city, branching into smaller streets and lanes (soi) which serve local neighbourhoods. Eleven bridges over the Chao Phraya link the two sides of the city, while several expressway and motorway routes bring traffic into and out of the city centre and link with nearby provinces. The first expressway in Bangkok is Chaloem Maha Nakhon Expressway, which opened 1981.

参考译文:曼谷的主要出行方式是基于道路的交通。由于这座城市的有机发展,其街道并没有遵循有组织的网格结构。48条主要道路连接着城市的不同区域,并分支出更小的街道和巷道(soi),为当地社区提供服务。湄南河上有11座桥梁连接着城市的两岸,同时还有几条高速公路和快速路线将交通引入和离开市中心,并与附近的省份相连。曼谷的第一条高速公路是查洛姆·马哈纳空高速公路(Chaloem Maha Nakhon Expressway),于1981年开通。

图片题注:暹罗天地的双塔

图片作者:Chainwit.

Bangkok’s rapid growth in the 1980s resulted in sharp increases in vehicle ownership and traffic demand, which have since continued—in 2006 there were 3,943,211 in-use vehicles in Bangkok, of which 37.6 per cent were private cars and 32.9 per cent were motorcycles.[123] These increases, in the face of limited carrying capacity, caused severe traffic congestion evident by the early 1990s. The extent of the problem is such that the Thai Traffic Police has a unit of officers trained in basic midwifery in order to assist deliveries which do not reach hospital in time.[124] While Bangkok’s limited road surface area (8 per cent, compared to 20–30 per cent in most Western cities) is often cited as a major cause of its traffic jams, other factors, including high vehicle ownership rate relative to income level, inadequate public transport systems, and lack of transportation demand management, also play a role.[125] Efforts to alleviate the problem have included the construction of intersection bypasses and an extensive system of elevated highways, as well as the creation of several new rapid transit systems. The city’s overall traffic conditions, however, remain poor.

参考译文:曼谷在20世纪80年代的快速增长导致了车辆拥有量和交通需求大幅增加,这种增长至今仍在持续。2006年,曼谷有3,943,211辆在用车辆,其中37.6%为私家车,32.9%为摩托车。由于承载能力有限,这些增加导致了严重的交通拥堵问题,早在1990年代初期就已显现。问题的严重程度以至于泰国交通警察组织了一支专门接受基本助产术培训的官员单位,以帮助那些无法及时到达医院的分娩情况。尽管曼谷的道路面积有限(仅占整个城市面积的8%,而大多数西方城市为20-30%),这常常被认为是交通堵塞的主要原因,但其他因素也起到了作用,包括相对收入水平较高的车辆拥有率、不充足的公共交通系统以及缺乏交通需求管理。为缓解这一问题,曼谷采取了各种措施,包括建设交叉路口绕行道和广泛的高架高速公路系统,以及推出了几个新的快速交通系统。然而,该市的整体交通状况仍然较差。

图片题注:曼谷大京都大厦

图片作者:Chainwit.

Traffic has been the main source of air pollution in Bangkok, which reached serious levels in the 1990s. But efforts to improve air quality by improving fuel quality and enforcing emission standards, among others, had visibly ameliorated the problem by the 2000s. Atmospheric particulate matter levels dropped from 81 micrograms per cubic metre in 1997 to 43 in 2007.[126] However, increasing vehicle numbers and a lack of continued pollution-control efforts threatens a reversal of the past success.[127] In January–February 2018, weather conditions caused bouts of haze to cover the city, with particulate matter under 2.5 micrometres (PM2.5) rising to unhealthy levels for several days on end.[128][129]

参考译文:交通是曼谷空气污染的主要来源,这一问题在20世纪90年代达到了严重的程度。然而,通过改善燃料质量、执行排放标准等措施,努力改善空气质量的工作在2000年代已经取得了显著的成果。大气颗粒物水平从1997年的每立方米81微克下降到2007年的43微克。然而,不断增加的车辆数量和缺乏持续的污染控制工作使过去取得的成功面临逆转的威胁。2018年1月至2月,天气条件导致雾霾笼罩了这座城市,2.5微米以下的颗粒物(PM2.5)连续多天达到了不健康的水平。

图片题注:彩虹中心第二期

图片作者:Gerold Kogler

Although the BMA has created thirty signed bicycle routes along several roads totalling 230 kilometres (140 mi),[130] cycling is still largely impractical, especially in the city centre. Most of these bicycle lanes share the pavement with pedestrians. Poor surface maintenance, encroachment by hawkers and street vendors, and a hostile environment for cyclists and pedestrians, make cycling and walking unpopular methods of getting around in Bangkok.

参考译文:曼谷大都会区(BMA)在几条道路上共创造了30条标志清晰的自行车路线,总长230公里(140英里)。尽管如此,在曼谷市中心,骑自行车仍然非常不实际。大多数自行车道与人行道共用。路面维护不良、小贩和街头摊贩的侵占以及对骑车者和行人的不友好环境,使得骑自行车和步行成为在曼谷出行中不受欢迎的方式。

10.2 公交车和出租车 | Buses and taxis

图片题注:Many buses, minibuses and taxis share the streets with private vehicles at Victory Monument, a major public transport hub.

图片作者:Ilya Plekhanov

参考译文:在主要公共交通枢纽胜利纪念碑,许多巴士、小巴和出租车与私家车共用街道。

Bangkok has an extensive bus network providing local transit services within the Greater Bangkok area. The Bangkok Mass Transit Authority (BMTA) operates a monopoly on bus services, with substantial concessions granted to private operators. Buses, minibus vans, and song thaeo operate on a total of 470 routes throughout the region.[131] A separate bus rapid transit system owned by the BMA has been in operation since 2010. Known simply as the BRT, the system currently consists of a single line running from the business district at Sathon to Ratchaphruek on the western side of the city. The Transport Co., Ltd. is the BMTA’s long-distance counterpart, with services to all provinces operating out of Bangkok.

参考译文:曼谷拥有一个广泛的公交网络,为大曼谷地区提供本地交通服务。曼谷大众运输局(BMTA)垄断了公交服务,同时也授予私营运营商大量特许经营权。在整个地区有470条公交线路,包括公交车、小巴和Song Thaeo(一种类似于公共拼车出租车的交通工具)[131]。曼谷市政府拥有的独立快速公交系统(BRT)自2010年开始运营。该系统目前只有一条线路,从萨通商业区通往城市西部的Ratchaphruek。曼谷交通有限公司是BMTA的长途运营对应部门,负责运营往来曼谷和各个省份之间的服务。

Taxis are ubiquitous in Bangkok, and are a popular form of transport. As of August 2012, there are 106,050 cars, 58,276 motorcycles and 8,996 tuk-tuk motorized tricycles cumulatively registered for use as taxis.[132] Meters have been required for car taxis since 1992, while tuk-tuk fares are usually negotiated. Motorcycle taxis operate from regulated ranks, with either fixed or negotiable fares, and are usually employed for relatively short journeys.

参考译文:在曼谷,出租车是随处可见的,也是一种受欢迎的交通方式。截至2012年8月,共有106,050辆汽车、58,276辆摩托车和8,996辆嘟嘟车(一种三轮电动车)注册用于出租车服务[132]。自1992年起,汽车出租车必须使用计价器,而嘟嘟车的车费通常是商议的。摩托车出租车在指定的站点运营,车费可以是固定的或商议的,通常用于相对较短的行程。

Despite their popularity, taxis have gained a bad reputation for often refusing passengers when the requested route is not to the driver’s convenience.[133] Motorcycle taxis were previously unregulated, and subject to extortion by organized crime gangs. Since 2003, registration has been required for motorcycle taxi ranks, and drivers now wear distinctive numbered vests designating their district of registration and where they are allowed to accept passengers.

参考译文:尽管出租车很受欢迎,但它们因为经常在乘客要求的路线不方便时拒载而声誉不佳[133]。摩托车出租车以前没有受到监管,容易受到有组织犯罪团伙的勒索。自2003年以来,摩托车出租车站点开始要求注册,并且司机现在会穿着带有编号的背心,标明他们的注册区域和允许接载乘客的地点。

Several ride hailing super-apps operate within the city, including Grab (offering car and motorbike options),[134] and AirAsia in 2022.[135][136] The Estonian company Bolt launched airport transfer and ride hailing services in 2020. Ride sharing startup MuvMi launched in 2018, and operates an electric tuk-tuk service in 9 areas across the city.[137][138]

参考译文:曼谷市内有几个超级应用程序提供打车服务,包括Grab(提供汽车和摩托车选项)[134]以及2022年进入市场的AirAsia [135][136]。爱沙尼亚公司Bolt于2020年推出了机场接送和打车服务。于2018年推出的拼车创业公司MuvMi在曼谷市内的9个地区提供电动嘟嘟车服务[137][138]。

10.3 轨道交通 | Rail systems

Main article: Rail transport in Bangkok(主条目:曼谷轨道交通)

图片题注:A BTS train departs from Ratchadamri station, towards Siam station.

图片作者:Fabio Achilli from Milano, Italy

参考译文:BTS 列车从 Ratchadamri 站出发,前往 Siam 站。

10.3.1 城际铁路

辽观注:此标题使我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

图片题注:曼谷站(又称华喃峰车站)夜景

图片作者:Preecha.MJ

Bangkok is the location of Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Terminal, the new main terminus of the national rail network operated by the State Railway of Thailand (SRT). The older terminus, Bangkok (Hua Lamphong) Railway Station, which was the main station for Bangkok for over a century, remains in use. The SRT operates long-distance intercity services from Krung Thep Aphiwat, while commuter trains running to and from the outskirts of the city during the rush hour continue to operate at Bangkok (Hua Lamphong).

参考译文:曼谷是泰国国家铁路网络的新总站,名为Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Terminal,由泰国国家铁路(SRT)运营。而曼谷(Hua Lamphong)火车站是一个历史悠久的主要车站,已经使用了一个多世纪,仍然在使用中。SRT从Krung Thep Aphiwat提供长途城际服务,而通勤列车在高峰时段从市郊往返于曼谷(Hua Lamphong)火车站。

曼谷是泰国国家铁路的枢纽,北部本线、东北本线、南部本线、东部本线在此交汇。曼谷主要的火车站是曼谷站和挽赐站,由此可乘车至国内各府、马来西亚、老挝、柬埔寨。

目前曼谷正在建设曼谷近郊铁路系统,线路主要为高架铁路,沿既有线路布置,主要有暗红线、浅红线等线路。

10.3.2 曼谷集体运输系统

主条目:曼谷大众运输系统

图片作者:Ilya Plekhanov

Bangkok is served by four rapid transit systems: the BTS Skytrain, the MRT, the SRT Red Lines, and the elevated Airport Rail Link. Although proposals for the development of rapid transit in Bangkok had been made since 1975,[139] it was only in 1999 that the BTS finally began operation.

参考译文:曼谷有四个快速交通系统:BTS Skytrain,MRT,SRT红线和高架机场铁路。虽然自1975年以来就有关于曼谷发展快速交通的提案[139],但直到1999年BTS才正式开始运营。

曼谷集体运输系统简称为BTS,是曼谷市内的高架铁路系统,分为是隆线、素坤逸线与曼谷旅客捷运金线三条线路,经过市区主要商业购物娱乐区。运营时间自上午06:00至晚间12:00。车票费15-57泰铢。1999年12月5日,开通了三条约91千米的独立线路,乘客可以在暹罗车站(Siam)进行两线互相换乘;而在沙拉铃车站(Sala Daeng),莫集车站(Mo Chit)及亚索车站(Asok),乘客可以换乘曼谷地下铁路。2009年5月15日,开通了是隆线廷线(郑皇桥-大箩圈)。

The BTS consists of two lines, Sukhumvit and Silom, with 59 stations along 68.25 kilometres (42.41 mi).[140] The MRT opened for use in July 2004, and currently consists of two lines, the Blue Line and Purple Line with 53 stations along 70.6 kilometres (43.9 mi). The Airport Rail Link, opened in August 2010, connects the city centre to Suvarnabhumi Airport to the east. Its eight stations span a distance of 28.6 kilometres (17.8 mi). The SRT Red Lines (Commuter) opened in 2021, and consists of two lines, The SRT Dark Red Line and SRT Light Red Line with currently 14 stations along 41 kilometres (25 mi).

参考译文:BTS由Sukhumvit线和Silom线组成,共有59个车站,线路总长68.25公里(42.41英里)[140]。MRT于2004年7月开通,目前包括蓝线和紫线,共有53个车站,线路总长70.6公里(43.9英里)。机场铁路于2010年8月开通,将市中心与素万那普机场连接起来,共有8个车站,线路总长28.6公里(17.8英里)。SRT红线(通勤)于2021年开通,包括SRT深红线和SRT浅红线,目前共有14个车站,线路总长41公里(25英里)。

10.3.3 曼谷地铁

主条目:曼谷地铁

曼谷地铁简称为MRT,是曼谷的地下铁路系统,目前设有蓝线和紫线两条线路。曼谷的第一条地铁(MRTA[65])于2004年7月启用,从城市北端连到城市中心,共设有18个车站。1997年,由于泰国的政治及亚洲金融危机,使得原来由来自香港的合和实业财团(Hopewell)投资的高架电车计划被整个废弃,从曼谷华喃峰火车站一直到曼谷廊曼国际机场处处可以看见被废弃的钢筋混凝土支柱[66]。

曼谷地铁紫线连接曼谷市区和西北部的暖武里府,于2016年8月6日开始正式营运,以庆祝泰国国王拉玛九世普密蓬·阿杜德登基70周年,同时以庆祝诗丽吉王后84岁寿辰[67]。

Although initial passenger numbers were low and their service area was limited to the inner city until the 2016 opening of the Purple Line, which serves the Nonthaburi area, these systems have become indispensable to many commuters. The BTS reported an average of 600,000 daily trips in 2012,[141] while the MRT had 240,000 passenger trips per day.[142]

参考译文:尽管最初的乘客数量较少,并且服务范围仅限于内城区,直到2016年紫线开通,覆盖了Nonthaburi地区,但这些系统已经成为许多通勤者不可或缺的交通工具。2012年,BTS平均每天报告了60万人次的乘车次数[141],而MRT每天的客流量为24万人次[142]。

As of September 2020, construction work is ongoing to extend the city-wide transit system’s reach, including the construction of the Light Red grade-separated commuter rail line. The entire Mass Rapid Transit Master Plan in Bangkok Metropolitan Region consists of eight main lines and four feeder lines totaling 508 kilometres (316 mi) to be completed by 2029. In addition to rapid transit and heavy rail lines, there have been proposals for several monorail systems.

参考译文:截至2020年9月,曼谷正在进行延伸全市范围的交通系统建设工作,其中包括建设浅红色的高架通勤铁路线。整个曼谷都市区的大众快速交通总体规划包括八条主要线路和四条支线,总长度为508公里(316英里),计划于2029年完成。除了快速交通和重型铁路线路外,还有几个单轨列车系统的提案。

10.4 水路运输 | Water transport

图片题注:A Chao Phraya Express Boat on the Chao Phraya near Wat Arun

图片作者:Chainwit

参考译文:湄南河快艇在郑王庙附近的湄南河上行驶

Although much diminished from its past prominence, water-based transport still plays an important role in Bangkok and the immediate upstream and downstream provinces. Several water buses serve commuters daily. The Chao Phraya Express Boat serves thirty-four stops along the river, carrying an average of 35,586 passengers per day in 2010, while the smaller Khlong Saen Saep boat service serves twenty-seven stops on Saen Saep Canal with 57,557 daily passengers. Khlong Phasi Charoen boat service serves twenty stops on the Phasi Charoen Canal. Long-tail boats operate on fifteen regular routes on the Chao Phraya, and passenger ferries at thirty-two river crossings served an average of 136,927 daily passengers in 2010.[143]

参考译文:尽管水上交通在曼谷和上下游省份的重要性已经大大减弱,但仍然在曼谷和直接上下游省份中扮演着重要角色。每天有几条水上公交车为通勤者提供服务。湄南河快艇服务沿河设有34个站点,2010年平均每天运送35,586名乘客,而较小的Saen Saep运河小船服务沿运河设有27个站点,每天运送57,557名乘客。Phasi Charoen运河小船服务Phasi Charoen运河上的20个站点。长尾船在湄南河上运营15条常规路线,而32个河渡口的客运渡船在2010年平均每天运送136,927名乘客[143]。

Bangkok Port, popularly known by its location as Khlong Toei Port, was Thailand’s main international port from its opening in 1947 until it was superseded by the deep-sea Laem Chabang Port in 1991. It is primarily a cargo port, though its inland location limits access to ships of 12,000 deadweight tonnes or less. The port handled 11,936,855 tonnes (13,158,130 tons) of cargo in the first eight months of the 2010 fiscal year, about 22 per cent the total of the country’s international ports.[144][145]

参考译文:曼谷港口,通常以其所在地的名称Khlong Toei港口而闻名,自1947年开港起一直是泰国主要的国际港口,直到1991年被深海的Laem Chabang港取代。它主要是一个货物港口,尽管其内陆位置限制了船舶的吨位为12,000吨或以下。在2010财政年度的前八个月,该港口处理了11,936,855吨(13,158,130吨)的货物,约占该国国际港口总量的22%[144][145]。

10.5 机场 | Airports

图片题注:Suvarnabhumi Airport is home to flag carrier Thai Airways International.

图片作者:Alec Wilson from Khon Kaen, Thailand – 点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:素万那普机场是泰国国际航空公司的基地。

图片题注:素万那普国际机场

图片作者:Aero Icarus from Zürich, Switzerland – 点击这里访问原图链接

Bangkok is one of Asia’s busiest air transport hubs. Two commercial airports serve the city, the older Don Mueang International Airport and the newer Suvarnabhumi Airport. Suvarnabhumi, which replaced Don Mueang as Bangkok’s main airport after its opening in 2006, served 52,808,013 passengers in 2015,[146] making it the world’s 20th busiest airport by passenger volume. This volume exceeded its designed capacity of 45 million passengers. Don Mueang reopened for domestic flights in 2007,[147] and resumed international service focusing on low-cost carriers in October 2012.[148] Suvarnabhumi is undergoing expansion to increase its capacity to 60 million passengers by 2019 and 90 million by 2021.[149]

参考译文:曼谷是亚洲最繁忙的航空运输枢纽之一。该市有两个商业机场,一个是较老的廊曼国际机场,另一个是较新的素万那普机场。素万那普机场于2006年开放后取代廊曼机场成为曼谷的主要机场,2015年为52,808,013名乘客提供服务,使其成为世界上客运量排名第20的最繁忙机场。这个客流量超过了其设计容量4500万乘客。廊曼机场于2007年重新开放用于国内航班,并于2012年10月恢复了以低成本航空公司为重点的国际服务。素万那普机场正在进行扩建,计划到2019年将其容量增加到6000万乘客,到2021年增加到9000万乘客。

素万那普国际机场(或称为国家机场,BKK)位于城市东偏南方,是首都与周围主要的民用机场,是东南亚乃至亚洲重要的航空枢纽。机场从2002年开始建造,于2006年9月28日完工启用,以取代廊曼机场的业务。

廊曼国际机场(可称曼谷机场,DMK)曾是东南亚最繁忙的机场之一,位于城市的北方。主要为低成本航空、包机和非直飞航班起降[68]。

10.6 长途汽车

图片题注:曼谷至泰南长途汽车

图片作者:中文维基百科的美女森理世

曼谷有以下三个长途汽车站:

- 曼谷东站(Ekkamai),靠近BTS亿甲迈车站,由此可乘车至东部各府,如芭堤雅。

- 曼谷北站(Mo Chit),靠近BTS莫集车站,由此可乘车至北部与东北部各府。

- 曼谷南站(Bangkok Southern Bus Terminal),旧站位于曼谷莲区(Bangkok Noi),新站位于棠林詹区(Taling Chan)正在建设中[69],由此可乘车至南部各府,如普吉府、素叻府。

旺季时一般每半小时有一班长途汽车前往各旅游胜地。

新机场的二号场站外亦有汽车前往芭堤雅、孔敬府、呵叻府、廊开府等地,省却那些不想参观曼谷的游客极多时间。

11. 教育 | Education

图片题注:朱拉隆功大学的校园在1917年成立时被乡村包围,巴吞旺县在此后进行开发,也从此成为曼谷市中心的一部分

图片作者:Tangmo~commonswiki

曼谷长期以来一直是泰国现代教育的中心。该国第一所学校于19世纪后期在这里建立,现在全市有 1,351所学校。这座城市是该国五所最古老的大学的所在地,包括朱拉隆功大学、法政大学、泰国农业大学、玛希敦大学和泰国艺术大学均创立于1917 年至1943年之间。此后,这座城市继续保持其主导地位,尤其是在高等教育方面。

该国的大多数公立和私立大学都位于曼谷或大都会地区。朱拉隆功大学和玛希敦大学少数进入QS世界大学排名的泰国大学。 同样位于曼谷的吞武里国王科技大学是泰国唯一一所进入2012-13年泰晤士高等教育世界大学排名前400名的大学。

在过去的几十年里,攻读大学学位的大趋势促使新大学的成立以满足泰国学生的需求。因此曼谷不仅成为移民和泰国本地人寻找工作机会的地方,也是能够获得大学学位的重要城市。蓝甘亨大学在1971年成为泰国第一所开放大学;它现在拥有全国最高的入学率。对高等教育的需求导致许多其他公立和私立大学和学院的成立。虽然在主要省份建立了许多大学,但大曼谷地区仍然是大多数机构的所在地,而且该市的高等教育领域仍然充斥着非曼谷人。这种情况也不仅限于高等教育。

在1960年代,60% 至70%的10至19岁在校学生经常移居曼谷接受中学教育。这是由于各省缺乏中学,以及首都教育水平较高的结果。尽管这种差异在当代已经大大减少,但仍有数万名学生在争夺曼谷一流学校的名额。长期以来,教育一直是曼谷中央集权的主要因素,并将在政府为国家权力所造的努力中发挥重要的教育作用。

- 国立朱拉隆功大学(จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย)

- 国立玛希敦大学(มหาวิทยาลัยมหิดล)

- 国立法政大学(มหาวิทยาลัยธรรมศาสตร์)

- 国立泰国农业大学(มหาวิทยาลัยเกษตรศาสตร์)

- 私立曼谷大学(มหาวิทยาลัยกรุงเทพ)

- 国立纳烈宣大学 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) (มหาวิทยาลัยนเรศวร)

- 国立诗纳卡宁威洛大学(มหาวิทยาลัยศรีนครินทร์วิโรฒ)

- 国立先皇技术学院(叻甲挽)(สถาบันเทคโนโลยีพระจอมเกล้าเจ้าคุณทหารลาดกระบัง)

- 国立先皇技术学院(拍那空北)(มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีพระจอมเกล้าพระนครเหนือ)

- 国立先皇技术大学(吞武里)(มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีพระจอมเกล้าธนบุรี)

12. 卫生健康 | Healthcare

图片题注:Siriraj Hospital, established in 1888, is the oldest hospital in Thailand.

图片作者:Preecha.MJ

参考译文:Siriraj 医院成立于 1888 年,是泰国最古老的医院。

Much of Thailand’s medical resources are disproportionately concentrated in the capital. In 2000, Bangkok had 39.6 per cent of the country’s doctors and a physician-to-population ratio of 1:794, compared to a median of 1:5,667 among all provinces.[154] The city is home to 42 public hospitals, five of which are university hospitals, as well as 98 private hospitals and 4,063 registered clinics.[dead link][155] The BMA operates nine public hospitals through its Medical Service Department, and its Health Department provides primary care through sixty-eight community health centres. Thailand’s universal healthcare system is implemented through public hospitals and health centres as well as participating private providers.

参考译文:泰国的医疗资源在很大程度上不平衡地集中在首都曼谷。在2000年,曼谷拥有全国39.6%的医生,医生与人口的比例为1:794,而全国各省份的中位数为1:5,667[154]。该市拥有42所公立医院,其中五所是大学医院,还有98所私立医院和4,063个注册诊所。曼谷都市行政局通过其医疗服务部门运营着九家公立医院,其卫生部门通过68个社区卫生中心提供初级医疗保健服务。泰国的全民医疗保健系统通过公立医院、卫生中心以及参与的私营提供者实施。

Research-oriented medical school affiliates such as Siriraj, King Chulalongkorn Memorial and Ramathibodi Hospitals are among the largest in the country, and act as tertiary care centres, receiving referrals from distant parts of the country. Lately, especially in the private sector, there has been much growth in medical tourism, with hospitals such as Bumrungrad and Bangkok Hospital, among others, providing services specifically catering to foreigners. An estimated 200,000 medical tourists visited Thailand in 2011, making Bangkok the most popular global destination for medical tourism.[156]

参考译文:以Siriraj、君迪隆宫纪念和拉玛乌塔医院为代表的面向研究的医学院附属医院是泰国最大的医院之一,它们充当着三级护理中心,接收来自全国各地的转诊病人。近年来,特别是在私营部门,医疗旅游业有很大的增长,包括缅甸格兰和曼谷医院在内的医院专门为外国人提供服务。据估计,2011年有约20万名医疗旅游者访问泰国,使曼谷成为全球最受欢迎的医疗旅游目的地[156]。

图片题注:曼谷四季水岸香榭

图片作者:Chainwit.

13. 犯罪和安全 | Crime and safety

图片题注:Political violence has at times spilled onto the streets of Bangkok, as seen during the military crackdown on protesters in 2010.

参考译文:政治暴力有时会蔓延到曼谷街头,正如 2010 年军事镇压抗议者时所见。

图片作者:Takeaway

Bangkok has a relatively moderate crime rate when compared to urban counterparts around the world.[157] Traffic accidents are a major hazard[158] while natural disasters are rare. Intermittent episodes of political unrest and occasional terrorist attacks have resulted in losses of life.

参考译文:与世界各地的城市相比,曼谷的犯罪率相对较低[157]。交通事故是一个主要的危险因素[158],而自然灾害很少发生。政治动荡的间歇性事件和偶发的恐怖袭击导致了人员伤亡。

Although the crime threat in Bangkok is relatively low, non-confrontational crimes of opportunity such as pick-pocketing, purse-snatching, and credit card fraud occur with frequency.[157] Bangkok’s growth since the 1960s has been followed by increasing crime rates partly driven by urbanisation, migration, unemployment and poverty. By the late 1980s, Bangkok’s crime rates were about four times that of the rest of the country. The police have long been preoccupied with street crimes ranging from housebreaking to assault and murder.[159] The 1990s saw the emergence of vehicle theft and organized crime, particularly by foreign gangs.[160] Drug trafficking, especially that of ya ba methamphetamine pills, is also chronic.[161][162]

参考译文:尽管曼谷的犯罪威胁相对较低,但机会性非对抗性犯罪,如扒窃、抢劫钱包和信用卡诈骗,仍然频繁发生[157。自20世纪60年代以来,曼谷的增长伴随着犯罪率的上升,部分原因是城市化、人口迁移、失业和贫困。到20世纪80年代末,曼谷的犯罪率约为全国其他地区的四倍。警方长期以一直忙于应对从入室盗窃到袭击和谋杀等街头犯罪[159]。20世纪90年代出现了车辆盗窃和有组织犯罪,尤其是外国团伙的活动[160]。毒品走私,特别是摇头丸甲基苯丙胺药丸的走私问题也很普遍[161][162]。

According to police statistics, the most common complaint received by the Metropolitan Police Bureau in 2010 was housebreaking, with 12,347 cases. This was followed by 5,504 cases of motorcycle thefts, 3,694 cases of assault and 2,836 cases of embezzlement. Serious offences included 183 murders, 81 gang robberies, 265 robberies, 1 kidnapping and 9 arson cases. Offences against the state were by far more common, and included 54,068 drug-related cases, 17,239 cases involving prostitution and 8,634 related to gambling.[163] The Thailand Crime Victim Survey conducted by the Office of Justice Affairs of the Ministry of Justice found that 2.7 per cent of surveyed households reported a member being victim of a crime in 2007. Of these, 96.1 per cent were crimes against property, 2.6 per cent were crimes against life and body, and 1.4 per cent were information-related crimes.[164]

参考译文:根据警方统计数据,2010年曼谷都会警察局收到的最常见投诉是入室盗窃,共有12,347起案件。其次是5,504起摩托车盗窃案、3,694起袭击案和2,836起贪污案。严重的犯罪包括183起谋杀案、81起团伙抢劫案、265起抢劫案、1起绑架案和9起纵火案。针对国家的犯罪远远更为普遍,其中包括54,068起与毒品相关的案件、17,239起涉及卖淫的案件和8,634起涉及赌博的案件[163]。泰国司法部司法事务办公室进行的《泰国犯罪受害者调查》发现,2007年有2.7%的受访家庭报告称其成员成为犯罪受害者。其中,96.1%是财产犯罪,2.6%是针对生命和身体的犯罪,1.4%是与信息相关的犯罪[164]。

Political demonstrations and protests are common in Bangkok. The historic uprisings of 1973, 1976 and 1992 are infamously known for the deaths from military suppression. Most events since then have been peaceful, but the series of major protests since 2006 have often turned violent. Demonstrations during March–May 2010 ended in a crackdown in which 92 were killed, including armed and unarmed protesters, security forces, civilians and journalists. Terrorist incidents have also occurred in Bangkok, most notably the bombing in 2015 at the Erawan shrine, which killed 20, and also a series of bombings on the 2006–07 New Year’s Eve.

参考译文:曼谷经常发生政治示威和抗议活动。1973年、1976年和1992年的历史性起义以军队镇压造成的死亡而臭名昭著。自那时以来,大多数事件都是和平的,但自2006年以来的一系列重大抗议活动经常变得暴力。2010年3月至5月的示威活动以镇压结束,期间有92人死亡,包括武装和非武装抗议者、安全部队、平民和记者。曼谷也发生过恐怖袭击事件,尤其是2015年的四面佛爆炸案,造成20人死亡,还有在2006-2007年新年夜的一系列爆炸事件。

Traffic accidents are a major hazard in Bangkok. There were 37,985 accidents in the city in 2010, resulting in 16,602 injuries and 456 deaths as well as 426.42 million baht in damages. However, the rate of fatal accidents is much lower than in the rest of Thailand. While accidents in Bangkok amounted to 50.9 per cent of the entire country, only 6.2 per cent of fatalities occurred in the city.[165] Another serious public health hazard comes from Bangkok’s stray dogs. Up to 300,000 strays are estimated to roam the city’s streets,[166] and dog bites are among the most common injuries treated in the emergency departments of the city’s hospitals. Rabies is prevalent among the dog population, and treatment for bites pose a heavy public burden.[m]

参考译文:交通事故是曼谷的一个重大危险。2010年,该市发生了37,985起交通事故,造成16,602人受伤和456人死亡,损失达到4.2642亿泰铢。然而,致命事故的比率远低于泰国其他地区。尽管曼谷的事故占全国总数的50.9%,但只有6.2%的死亡事故发生在该市[165]。另一个严重的公共健康危险来自曼谷的流浪狗。据估计,该市有多达30万只流浪狗漫游街头[166],狗咬伤是该市医院急诊科最常见的伤害之一。狂犬病在狗群中很常见,咬伤的治疗对公众来说是个巨大的负担[m]。

对搬移首都的呼吁 | Calls to move the capital

Bangkok is faced with multiple problems—including congestion, and especially subsidence and flooding—which have raised the issue of moving the nation’s capital elsewhere. The idea is not new: during World War II Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram planned unsuccessfully to relocate the capital to Phetchabun. In the 2000s, the Thaksin Shinawatra administration assigned the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) to formulate a plan to move the capital to Nakhon Nayok province. The 2011 floods revived the idea of moving government functions from Bangkok. In 2017, the military government assigned NESDC to study the possibility of moving government offices from Bangkok to Chachoengsao province in the east.[168][169][170]

参考译文:曼谷面临着多种问题,包括交通拥堵,尤其是地面下沉和洪水,这引发了将国家首都迁至其他地方的问题。这个想法并不新鲜:在第二次世界大战期间,前总理排泰·巴育曾计划将首都迁至河北府,但未能成功。在2000年代,他信政府委托国家经济和社会发展委员会办公室制定了将首都迁至那空那育府的计划。2011年的洪水再次唤起了将政府职能从曼谷迁移的想法。2017年,军政府委派国家经济和社会发展委员会研究将政府办公室从曼谷迁至东部的查干沙万府的可能性[168][169][170]。

14. 国际关系 | International relations

图片题注:Protesters in front of the United Nations Building during the 2009 Bangkok Climate Change Conference. Bangkok is home to several UN offices.

图片作者:Shubert Ciencia from Nueva Ecija, Philippines – 点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:2009 年曼谷气候变化会议期间,抗议者在联合国大楼前。 曼谷是多个联合国办事处的所在地。

The city’s formal international relations are managed by the International Affairs Division of the BMA. Its missions include partnering with other major cities through sister city or friendship agreements, participation and membership in international organizations, and pursuing cooperative activities with the many foreign diplomatic missions based in the city.[171]

参考译文:曼谷市的正式国际关系由曼谷都市管理局的国际事务部管理。其任务包括通过姐妹城市或友好协议与其他主要城市建立伙伴关系,参与和成为国际组织的成员,并与驻扎在该市的许多外国使团进行合作活动[171]。

14.1 国际参与 | International participation