辽观搬运、翻译、整合的中英文维基百科词条。与原维基百科词条同样遵循CC-BY-SA 4.0协议,在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。

中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目(点击这里了解更多),其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。 辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

目录

- 0. 概述

- 1. 历史 | History

- 2. 人口 | Population

- 3. 徽标 | Emblem

- 4. 宗教名胜 | Religious Sites

- 5. 管理 | Administration

- 6. 文化 | Culture

- 7. 教育 | Education

- 8. 环境 | Environment

- 9. 自然公园 | Nature

- 10. 娱乐 | Recreation

- 11. 健康 | Health

- 12. 交通 | Transportation

- 13. “智慧城市”倡议 | “Smart City” initiative

- 14. 旅游业 | Tourism

- 15. 知名人士 | Notable persons

- 16. 友好城镇和姊妹城市 | Twin towns and sister cities

- 18. 参见(相关维基百科词条)

- 19. 参考文献

- 20. 外部链接

0. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

0.1 概况表格

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

图片题注:Official seal of Chiang Mai

参考译文:清迈官方印章

(1)概述 | Overview

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

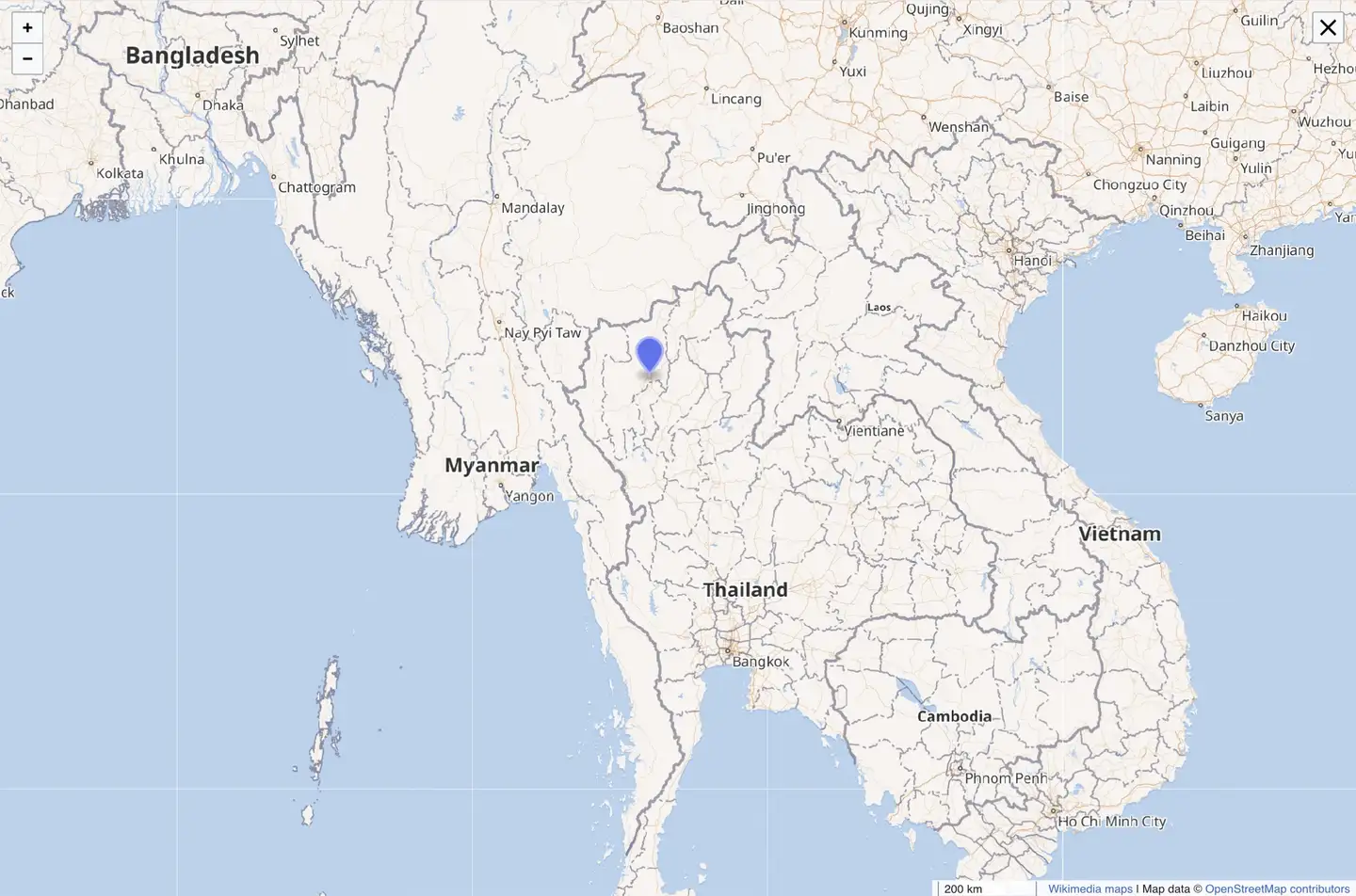

| Location within Earth(在地球上的位置) | Coordinates(坐标): 18°47′43″N 98°59′55″E |

|---|---|

| Elevation(海拔高度) | 310 m (1,020 ft) |

| Country(国家) | Thailand(泰国) |

| Province(省份) | Chiang Mai province(清迈省) |

| Amphoe(市级单位) | Mueang Chiang Mai |

| Districts(市辖区) | 4 Nakornping District Kawila District Mengrai District Sriwichai District |

| Time zone(时区) | UTC+07:00 (ICT)(东七区) |

| Website(网站) | cmcity.go.th |

(2)政府

| 类型 Type | City municipality |

|---|---|

| 市长 Mayor | Atsani Puranupakorn |

| City municipality(设市时间) | 29 March 1935[1] |

(3)面积 | Area

| City municipality(市辖区) | 40.216 km2 (15.5274844 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Urban(都会区) | 405 km2 (156.371 sq mi) |

| Rank(排名) | 11th(第11位) |

(4)人口(2019年) | Population(2019)

| City municipality(市辖区) | 127,240(Municipal Area(仅管辖区域)) |

|---|---|

| Rank(排名) | 8th(第8位) |

| Density(人口密度) | 3,164/km2 (8,190/sq mi) |

| Urban (2022)(都会区,2022年) | 1,198,000 (Principal City Area/เขตเมือง (主城区)) |

| Urban density(都会区人口密度) | 2,958/km2 (7,660/sq mi) |

| Metro(中心区) | (To be announced(尚待发布)) |

(4)交通和通讯

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

| Postal code(邮政编码) | 50000 |

|---|---|

| Calling code(电话区号) | 053 & 054 |

| Airport(机场) | Chiang Mai International Airport(清迈国际机场) |

| Inter-city rail(城际铁路) | Northern Line(北线) |

0.2 文字说明

清迈市(泰语:เทศบาลนครเชียงใหม่,皇家转写:Thesaban nakhon Chiang Mai,罗马化:jʸang hᵐa̰ɯ̰)是清迈府的首府清迈府治县的一部分,也是泰国北部政治、经济、文化的中心。人口约120 万人。清迈是泰国第二大城市。

虽然清迈市区内的人口只有25万,但是在整个泰北与邻近卫星城镇,形成了一个清迈都会生活圈,该都会区有 120 万人,占了清迈府一半人口以上。

清迈是泰国北部最大的历史文化城市,也是泰北政治经济中心。为清迈府首府,在1296年至1768年间为兰纳王国首都,兰纳王国其后于1774-1939发展为清迈王国的朝贡国。清迈距离曼谷700千米,倚靠着泰国最高的山。清迈在平河的流域中,平河是昭拍耶河的主要支流。清迈在泰语的意思是新城市,在兰纳王国1296年订定首都时所取的。清迈取代了清莱成为兰纳的首都。

The city (thesaban nakhon,“city municipality”) of Chiang Mai officially only covers most parts (40,2 km²) of the Mueang Chiang Mai district in the city centre and has a population of 127,000[citation needed]. This census area dates back to 1983 when Chiang Mai’s municipal area was enlarged for the first and last time since becoming the first City Municipality in Thailand (then under Siam) in 1935. The city’s sprawl has since extended into several neighboring districts, from Hang Dong in the south, to Mae Rim in the north, and Suthep in the west, to San Kamphaeng in the east, forming the Chiang Mai urban area with over a million residents.

参考译文:清迈市(thesaban nakhon,”城市市政”)仅覆盖了市中心的Mueang Chiang Mai区的大部分地区(40.2平方公里),人口为127,000人[引用需要]。这个人口普查区可以追溯到1983年,当时清迈的市政区域自1935年成为泰国第一个城市自治市以来首次也是最后一次扩大。此后,该市的扩张已扩展到几个邻近的地区,从南部的Hang Dong到北部的Mae Rim,再到西部的Suthep,再到东部的San Kamphaeng,形成了拥有超过一百万居民的清迈市区。

清迈在2006年东盟加三于清迈签订清迈协定时得到显著的政治地位。清迈同时是2020年泰国大城府世界博览会展场之一。清迈被定位成一个文创城市,目前正在申请联合国教科文组织的世界创意城市中。清迈也是旅游胜地,曾被旅游杂志TripAdvisor票选为2014年世界25大最佳旅游地,并获选为第24名。

清迈位于平河流域以及主要贸易枢纽的位置使他具有相当历史重要性。

清迈被下设四个行政区、洛平、室利佛逝、曼格莱和卡威拉。前三个行政区位于平河西岸,卡威拉则位于东岸。而城市的中心位于室利佛逝。

1. 历史 | History

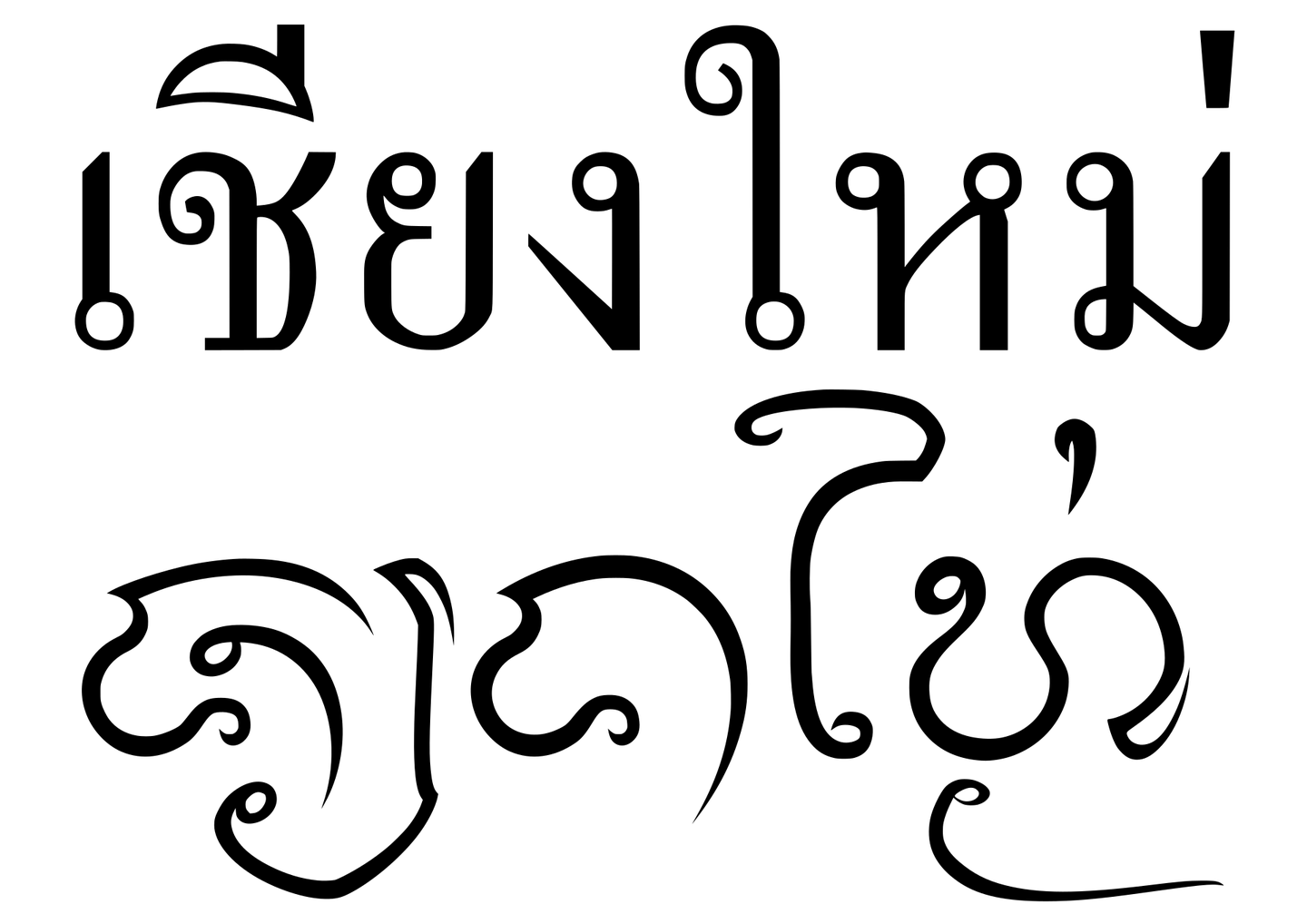

维基百科的图片说明:”Chiang Mai” in Thai language(top) and Northern Thai with Tai Tham script(bottom)

图片作者:Autoisme

参考译文:泰语中的”清迈”(顶部)和北部泰语的泰泰文(底部)

Historical affiliations(历史背景)

Kingdom of Ngoenyang 638–1292Kingdom of Ngoenyang 638–1292 (恩杨王国 638–1292)

Kingdom of Lanna 1292-1775 (兰纳王国 1292-1775)

Kingdom of Chiang Mai 1775-1899 (清迈王国 1775-1899 年)

Kingdom of Siam 1899-1946 (暹罗王国 1899-1946)

Kingdom of Thailand 1946-present (泰王国 1946 年至今)

原为罗涡人城镇那婆补罗镇或渊诺帕武里(转写为泰语:เวียงนพบุรี,转写:wyiːeng nabaqpuriː)。

1296年[1]由孟莱王(孟莱王的母亲是西双版纳景洪统治者的女儿,父亲是清盛一带的统治者。孟莱建立了清莱和清迈两座城市,领导兰纳和西双版纳傣族人民抗击蒙古侵略者,使兰纳历史上出现了第一次高峰。傣族后人为了纪念他,把一部法典命名为“孟莱法典”,流传于泰国北部和西双版纳。)从清莱迁至该地,起了城墙与护城河,将该地建设成兰纳泰王国(中文史料称兰纳泰王国为“八百媳妇国”)的首都挪婆部里室利那竭罗凭伽景买(老傣文:nᶭabᵇaqpuriː sriː nagᵚar(a) bingg̶a̶ jʸang hᵐa̰ɯ̰)。

The ruler was known as the chao. The city was surrounded by a moat and a defensive wallsince nearby Taungoo Dynasty of the Bamar people was a constant threat, as were the armies of the Mongol Empire, which decades earlier had conquered most of Yunnan, China, and in 1292 overran the bordering Dai kingdom of Chiang Hung.

参考译文:统治者被称为chao 。这座城市被护城河和防御墙包围,因为附近的巴马人的东固王朝是一个持续的威胁,蒙古帝国的军队也是如此,几十年前他们征服了中国云南的大部分地区,并在1292年越过边界占领了江洪的傣族王国。

14世纪以来,兰纳泰王国受佛教影响,在清迈建立很多佛寺,逐渐成为佛教圣地。

1477年兰纳泰的提洛卡拉王在柴迪隆寺举行第8次世界佛教会议,是为清迈市的黄金时代。

1564年起被缅甸控制。

With the decline of Lan Na, the city lost importance and was occupied by the Taungoo in 1556.[13][failed verification] Chiang Mai formally became part of the Thonburi Kingdom in 1774 by an agreement with Chao Kavila, after the Thonburi king Taksin helped drive out the Taungoo Bamar. Subsequent Taungoo counterattack led to Chiang Mai’s abandonment between 1776 and 1791.[14] Lampang then served as the capital of what remained of Lan Na. Chiang Mai then slowly grew in cultural, trading, and economic importance to its current status as the unofficial capital of Northern Thailand.

参考译文:随着兰纳的衰落,这座城市失去了重要性,并于1556年被东固占领。[13][未能验证] 1774年,在Thonburi国王Taksin帮助驱逐了东固巴马后,清迈与Chao Kavila达成协议,正式成为吞武里王国的一部分。随后的东固反击导致清迈在1776年至1791年间被放弃。[14]然后,Lampang作为兰纳剩余部分的首都。清迈随后逐渐在文化、贸易和经济方面发展壮大,成为泰国北部的非正式首都。

19世纪中叶后期,拉玛五世就任暹罗国王,撤销藩王制度,将清迈地区置府(省),清迈市成为清迈府的首府。

Chiang Mai has improved its government and raised its status as a “province” since 1933 until the present.

参考译文:自1933年至今,清迈提升了它的政府并被提升到了“省”的地位。

The modern municipality dates to a sanitary district (sukhaphiban) that was created in 1915. It was upgraded to a city municipality (thesaban nakhon) on 29 March 1935.[15] First covering just 17.5 km2 (7 sq mi), the city was enlarged to 40.2 km2 (16 sq mi) on 5 April 1983.[16]

参考译文:现代市政当局可以追溯到1915年成立的一个卫生区(sukhaphiban)。它于1935年3月29日升级为市自治市(thesaban nakhon)。[15]最初只覆盖了17.5平方公里(7平方英里),该市于1983年4月5日扩大到40.2平方公里(16平方英里)。[16]

1980年代起,清迈渐渐发展成泰国北部重要城市和旅游中心。

In May 2006 Chiang Mai was the site of the Chiang Mai Initiative, concluded between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the “ASEAN+3” countries, (China, Japan, and South Korea). Chiang Mai was one of three Thai cities contending for Thailand’s bid to host the World Expo 2020.[17] Ayutthaya was ultimately chosen by the Thai Parliament to register for the international competition.[18]

参考译文:2006年5月,清迈是东南亚国家联盟和”东盟+3″国家(中国、日本和韩国)之间缔结的《清迈倡议》的所在地。清迈是泰国三个竞标主办2020年世界博览会的城市之一。[17]最终,泰国议会选择了阿育他耶参加国际竞争。[18]

In early December 2017, Chiang Mai was awarded the UNESCO title of Creative City. In 2015, Chiang Mai was on the tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage inscription. Chiang Mai was one of two tourist destinations in Thailand on TripAdvisor‘s 2014 list of “25 Best Destinations in the World,” where it stands at number 24.[19]

参考译文:2017年12月初,清迈被联合国教科文组织授予创意城市称号。2015年,清迈被列入联合国教科文组织世界遗产暂定名单。清迈是TripAdvisor 2014年“全球25个最佳旅游目的地”中泰国两个旅游目的地之一,排名第24位。[19]

“…Chiang Mai represents the prime diamond on the crown of Thailand, the crown cannot be sparkle and beauteous without the diamond…”

— 国王拉玛五世,1883年8月12日

— King Rama V, 12 August 1883

参考译文:”清迈是泰国皇冠上的一颗主要钻石,没有这颗钻石,皇冠就不会闪耀美丽…”

泰国清迈城、老挝琅勃拉邦城、中国景洪城和缅甸景栋城并称兰纳王国四大城市,后来在历史流变中,分属于四个国家。但至今这四座城市的方言差异很小,可以互通。

2. 人口 | Population

Further information: List of municipalities in Thailand (更多信息:泰国城市列表)

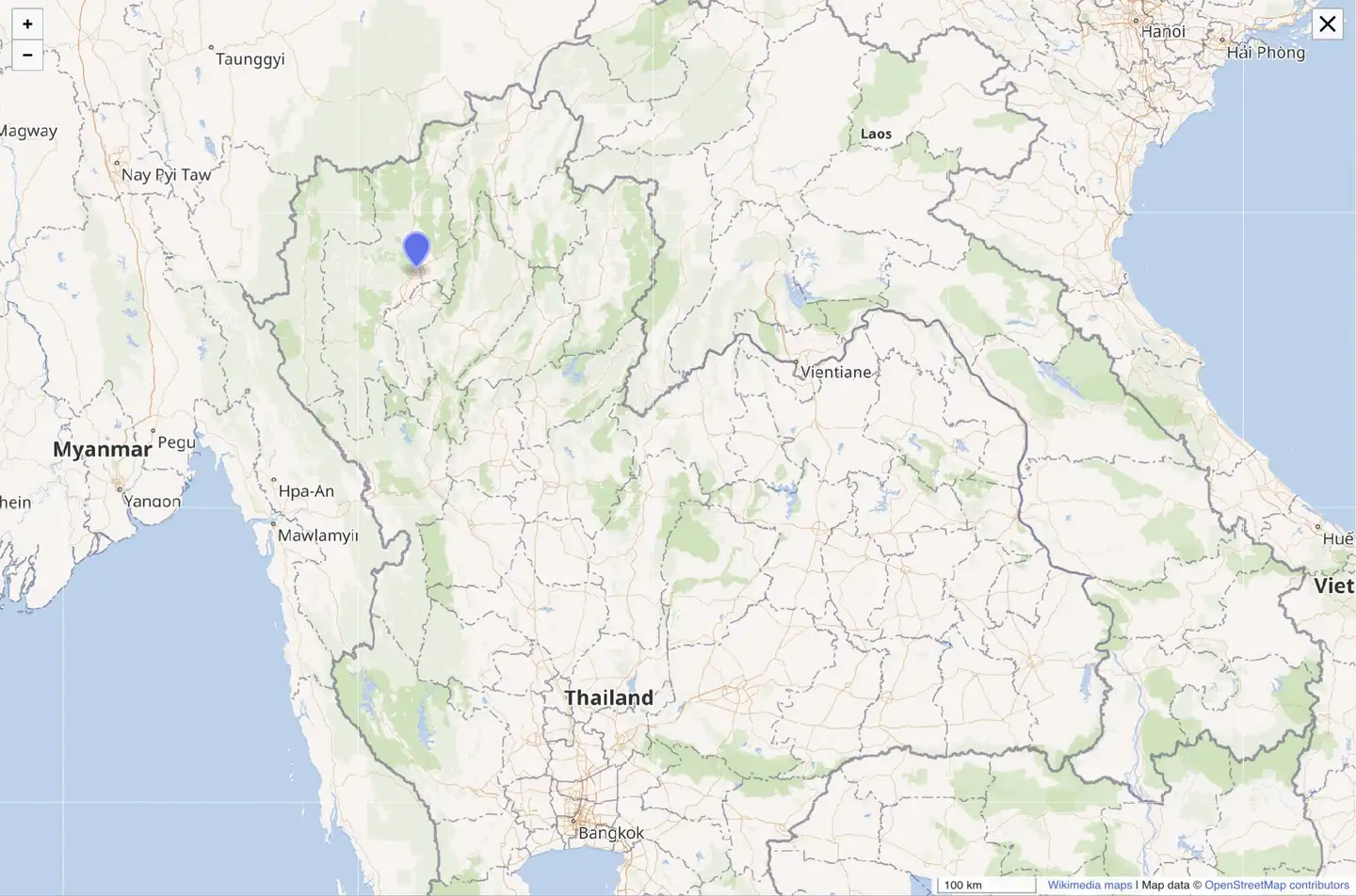

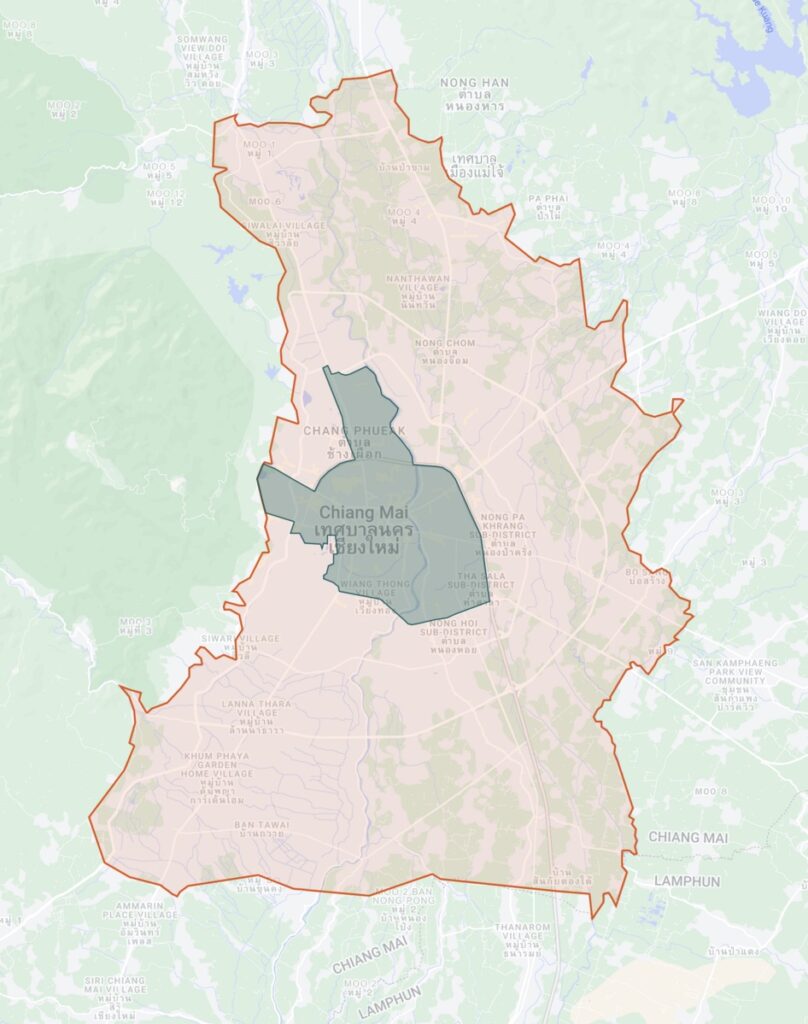

Ever since the municipal city area was enlarged to 40,2 km² in 1983, no changes or updates have been made to it, even with the population increasing substantially in the years after.[16] In 1983, Chiang Mai’s urban area, with a population of 127,000, already exceeded the municipal city limits, and has grown to over one million people in 2022.[3]

参考译文:自1983年市政城市面积扩大到40.2平方公里以来,尽管人口在随后的几年里大幅增加,但该市一直没有进行任何改变或更新。[16] 1983年,清迈的城市区域人口为12.7万人,已经超过了市政城市限制,到2022年已经增长到超过100万人。[3]

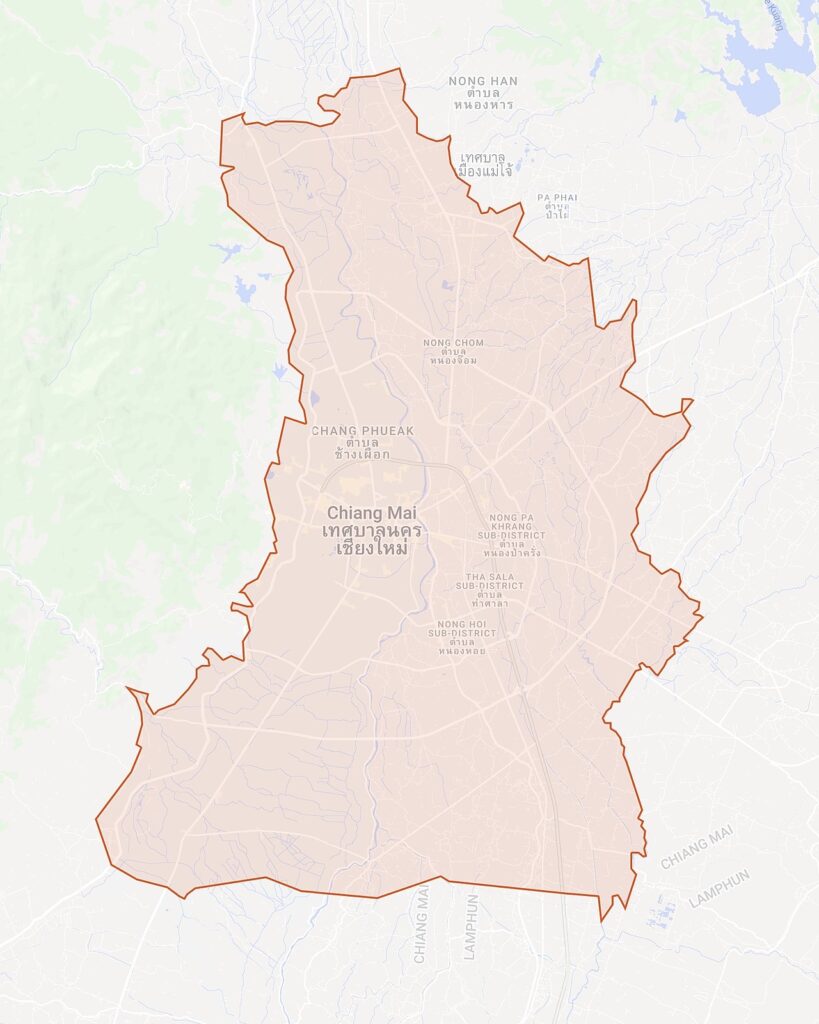

Chiang Mai Municipality has now become a small part of the current city-scape, making up only most parts of the capital district Amphoe Mueang Chiang Mai in the inner city. To reflect the city’s growth beyond the municipal borders, official government documents by the Chiang Mai Provincial Administrative Organization and the Department of Public Works and Town & Country Planning – published in the Royal Thai Government Gazette – regularly update and outline the current city boundaries. The first revision of such a updated urban area (Thai: เขตเมือง) was published in 1989, with the second one following in 1999. The third revision from 2012 expands the old municipal city border inside Muaeng Chiang Mai district to Mae Rim in the north, San Kamphaeng and Doi Saket in the east, Hang Dongand Saraphi in the south, and Suthep in the west.[20][21][22] This new extent, with a size of 405 km², serves as Chiang Mai’s principal city border and urban area.

参考译文:现在的清迈市已经成为了当前城市景观的一小部分,只占内城首都区Amphoe Mueang Chiang Mai的大部分。为了反映城市在市政边界之外的发展,由清迈省行政组织和公共工程与城市规划部门发布的官方政府文件定期更新并概述当前的城市边界,这些信息发布在泰国皇家政府公报上。第一次修订这样的城市区域是在1989年,第二次是在1999年。2012年的第三次修订将旧的市政城市边界从Muaeng Chiang Mai区扩展到北部的Mae Rim,东部的San Kamphaeng和Doi Saket,南部的Hang Dong和Saraphi,以及西部的Suthep。这个新的范围,面积为405平方公里,是清迈的主要城市边界和城市区域。

The urban area has a combined population of 1,198,000 residents, making Chiang Mai the second largest city in Thailand after Bangkok (10.7 million people) and twice as big as the third largest city Nakhon Ratchasima (Estimate: 500,000 people).[3][4] As neither the Department of Local Administration (DLA) nor the National Statistics Office (NSO) count expatriates, non-permanent residents, migrant workers (except ASEAN migrants for the year 2017) and citizens from other Thai provinces living and renting in Chiang Mai in their official population figures, it is estimated that the real population figure for Chiang Mai could be as high as 1.5 million.

参考译文:城市地区的总人口为1,198,000人,使清迈成为泰国第二大城市,仅次于曼谷(1070万人),是第三大城市Nakhon Ratchasima的两倍(估计:50万人)[3][4]。由于地方行政管理部门(DLA)和国家统计办公室(NSO)都没有将外籍人士、非永久居民、移民工人(除了2017年的ASEAN移民)和其他泰国省份在清迈生活和租房的公民计入官方人口数据中,因此估计清迈的实际人口可能高达150万人。

As of 2022, a fourth revision of Chiang Mai’s urban area is under way and currently up for debate by the public. Proposals show the expansion of the current urban area into more adjacent subdistricts and large forest areas, especially around Doi Suthep.[23][24]

参考译文:截至2022年,清迈的城市区域正在进行第四次修订,目前正由公众进行辩论。提案显示,将目前的城区扩展到更多的相邻分区和大片森林地区,特别是在素贴山周围。[23][24]

Since Thailand’s outdated census methods prevent the determination of official metropolitan areas outside of Bangkok, presently there are no official sources indicating how large the extended metropolitan area is. In the case of Chiang Mai, it is presumed that the area would cross provincial borders due to the city’s close proximity to Lamphun province.

参考译文:由于泰国过时的人口普查方法无法确定曼谷以外的官方都市区域,因此目前没有官方来源表明扩展后的都市区域有多大。在清迈的情况下,由于该市与南奔府的密切关系,可以推测该区域可能跨越省界。

Chiang Mai’s true size is often misinterpreted and misrepresented, unintentionally mitigating the city’s importance in Thailand.

参考译文:清迈的真实规模往往被误解和错误地呈现,无意中降低了该市在泰国的重要性。

【左图】

图片作者:Jonathan.Gab.

图片题注:Chiang Mai Municipality (40.216km², in green) inside the Chiang Mai Urban Area (405km², in red)[25]

参考译文:清迈市区(405 平方公里,红色)内的清迈市(40.216 平方公里,绿色)

【右图】

图片作者:Jonathan.Gab.

图片题注:Rendition of Chiang Mai’s principal city plan border (not the city proper’s border) defined by Chiang Mai’s Provincial Administrative Organization, Size: 405km²

参考译文:清迈省行政组织定义的清迈主要城市规划边界(不是市区边界)的效果图,面积:405平方公里

3. 徽标 | Emblem

The city emblem shows the stupa at Wat Phra That Doi Suthep in its center. Below it are clouds representing the moderate climate in the mountains of northern Thailand. There is a nāga, the mythical snake said to be the source of the Ping River, and rice stalks, which refer to the fertility of the land.[26]

【参考译文】城市徽标中心展示了茵他侬山上的茵他侬寺(Wat Phra That Doi Suthep)的佛塔。下方的云朵代表了泰国北部山区温和的气候。还有一条那伽(nāga),这是一种神话中的蛇,据说它是湄平河的源头,以及稻穗,象征着土地的肥沃。[26]

4. 宗教名胜 | Religious Sites

Chiang Mai city has 117 Buddhist temples (“wat” in Thai) in the Muang (city) district.[27] These include:

参考译文:清迈市的 Muang(市)区有 117 座佛教寺庙(泰语“wat”)。[27] 这些包括:

Wat Phra That Doi Suthep, the city’s most famous temple, stands on Doi Suthep, a mountain to the north-west of the city, at an elevation of 1,073 meters.[28] The temple dates from 1383.

参考译文:该市最著名的寺庙——位于素贴山上的佛塔,海拔1073米,建于1383年。

Wat Chiang Man, the oldest temple in Chiang Mai, dating from the 13th century.[6]: 209 King Mengrai lived here during the construction of the city. This temple houses two important and venerated Buddha figures, the marble Phra Sila and the crystal Phra Satang Man.

参考译文:Wat Chiang Man是清迈最古老的寺庙,建于13世纪。在建造城市期间,国王Mengrai曾在这里居住。该寺庙收藏了两个重要而受尊敬的佛像,分别是大理石的Phra Sila和水晶的Phra Satang Man。

Wat Phra Singh is within the city walls, dates from 1345, and offers an example of classic Northern Thai-style architecture. It houses the Phra Singh Buddha, a highly venerated figure brought here many years ago from Chiang Rai.[29]

参考译文:Wat Phra Singh位于城墙内,建于1345年,是北泰式建筑的经典范例。该寺庙收藏了Phra Singh Buddha,这是许多年前从清莱带来的备受尊崇的佛像。

帕邢寺(Wat Phra Singh):位于清迈古城内Rajdamnoen Road和Samlam Road交界。被视为清迈历史最悠久的佛寺之一,由孟莱王朝的坎福王建于1345年,目的是用来安奉其父王的灵骨。屹立该寺的大佛像,据说是由斯里兰卡请来的佛陀叫“帕辛”,不过外貌则是泰北风格。每年泼水节时帕邢寺会为佛像净身。

Wat Chedi Luang was founded in 1401 and is dominated by a large Lanna style chedi, which took many years to finish. An earthquake damaged the chedi in the 16th century and only two-thirds of it remains.[30]

参考译文:Wat Chedi Luang建于1401年,以一座大型的兰纳式佛塔为主导,花费了许多年才完成。在16世纪,一场地震破坏了佛塔,现在只有三分之二的部分仍然存在。

柴迪隆寺(Wat Chedi Luang):位于清迈古城的中央,柴迪隆寺在泰文的意思是“大塔寺”,又译作隆圣骨寺[3]。这座兰纳王朝建筑形式的大佛塔建于公元1441年原高90米,但经历1545年大地震和16世纪泰缅战争,现时寺庙略见倾颇,高度仅剩60米高。原存于此塔东面神龛的玉佛,后移至曼谷玉佛寺[4]。近年由联合国教科文组织和日本政府出资修缮,以保存原貌。

Wat Ku Tao in the city’s Chang Phuak District dates from (at least) the 13th century and is distinguished by an unusual alms-bowl-shaped stupa thought to contain the ashes of King Nawrahta Minsaw, Chiang Mai’s first Bamar ruler.[31]

参考译文:位于清迈Chang Phuak区的Wat Ku Tao至少可以追溯到13世纪,以其独特的碗状佛塔而闻名。据信,该佛塔内装有清迈第一位缅甸统治者Nawrahta Minsaw国王的骨灰。

Wat Chet Yot is on the outskirts of the city. Built in 1455, the temple hosted the Eighth World Buddhist Council in 1477.

参考译文:Wat Chet Yot 寺位于城市郊区。 该寺建于 1455 年,曾于 1477 年主办第八届世界佛教理事会。

Wiang Kum Kam is at the site of an old city in the Tha Wang Tan sub-district of the Saraphi district south of Chiang Mai. King Mangrailived there for ten years before the founding of Chiang Mai. The site includes many ruined temples.

参考译文:王堪干位于清迈南部萨拉菲区Tha Wang Tan分区的古城遗址。在建立清迈之前,曼格拉国王在那里居住了十年。该遗址包括许多被毁的寺庙。

Wat Umong is a forest and cave wat in the foothills west of the city, near Chiang Mai University. Wat U-Mong is known for its “fasting Buddha,” representing the Buddha at the end of his long and fruitless fast prior to gaining enlightenment.

参考译文:Wat Umong是一座位于城市西侧山脚下的森林和洞穴寺庙,靠近清迈大学。该寺庙以其“绝食佛像”而闻名,代表着佛陀在长期而无果的绝食之后获得启示的形象。

Wat RamPoeng (Tapotaram), near Wat U-Mong, is known for its meditation center (Northern Insight Meditation Center). The temple teaches the traditional vipassanā technique and students stay from 10 days to more than a month as they try to meditate at least 10 hours a day. Wat RamPoeng houses the largest collection of Tipitaka, the complete Theravada canon, in several Northern dialects.[32]

参考译文:Wat RamPoeng(塔波拉玛寺)靠近Wat U-Mong,以其冥想中心(北洞察冥想中心)而闻名。该寺庙教授传统的毗婆舍那技术,学生可以在这里停留10天到一个月以上,每天至少尝试冥想10小时。Wat RamPoeng拥有最大规模的Tipitaka收藏,包括完整的小乘经典和几种北方方言。

Wat Suan Dok is a 14th-century temple just west of the old city wall. It was built by the king for a revered monk visiting from Sukhothai for a rainy season retreat. The temple is also the site of Mahachulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya Buddhist University, where monks pursue their studies.[33]

参考译文:Wat Suan Dok是一座14世纪的寺庙,位于老城墙以西。它是由国王为一位来自素可泰的备受尊敬的僧侣建造的,供他在雨季进行静修。该寺庙也是玛哈朱拉隆功佛教大学(Maha Chulalongkorn Rajavidyalaya Buddhist University)的所在地,僧侣们在这里追求他们的学业。

松达寺(Wat Suan Duk):泰文意思是“花园寺”。此地位于清迈古城外西边,建于公元1373年,原本是为佛学大师素玛那泰拉(Phra Sumana Thera)雨季时的居所,后曾成为纳兰泰王朝的“御花园”,传说在松达寺的最大佛塔下埋了佛舍利子,而每个超过一人高的白色塔林亦是纳兰泰王室过世后埋葬处。此寺有一座建于16世纪的青铜佛像,每年4月清迈泼水节的主要仪式都会在该寺举行[5]。

清迈.蓝庙(Wat Ban Den):清迈蓝庙始建于公元1894年,位于清迈湄登县(Mae Taeng),从古城开车,经1001号公路,大约50公里,约70分钟就能到达。

In addition to the currently active temples there are several temple ruins scattered around the present-day city area. Typically only the main stupa remains as it is a brick and cement structure, with other temple buildings no longer there. There are 44 of such structures in the city area, ranging from very prominent landmarks to small remnants that have almost completely disappeared or are overgrown with vegetation.[34]

参考译文:除了目前仍在使用的寺庙外,在现今的城市区域周围散落着一些寺庙遗址。通常只有主要的佛塔仍然存在,因为它是由砖和水泥结构构成的,而其他寺庙建筑已经不复存在。在城市区域中共有44个这样的结构,从非常显著的地标到几乎完全消失或被植被覆盖的小遗迹不等。

Other religious traditions:

参考译文:其他宗教传统:

“First Church” was founded in 1868 by the Laos Mission of the Rev. Daniel and Mrs. Sophia McGilvary. Chiang Mai has about 20 Christian churches[35] Chiang Mai is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Chiang Mai at Sacred Heart Cathedral.

参考译文:”第一教堂”是由丹尼尔牧师和索菲亚·麦吉尔瓦里夫人于1868年创立的老挝教会。清迈大约有20个基督教堂[35]。清迈是位于圣心大教堂的罗马天主教清迈教区的所在地。

The office of the Christian Conference of Asia is located in Chiang Mai.

参考译文:亚洲基督教会议的办事处位于清迈。

Muslim traders have traveled to north Thailand for many centuries, and a small settled presence has existed in Chiang Mai from at least the middle of the 19th century.[36] The city has mosques identified with Chinese or Chin Haw Muslims as well as Muslims of Bengali, Pathan, and Malay descent. In 2011, there were 16 mosques in the city.[37]

参考译文:穆斯林商人已经前往泰国北部旅行了多个世纪,并且在清迈至少从19世纪中叶开始就存在一个小规模的定居点。[36]该市有与中国或云南穆斯林有关的清真寺,以及孟加拉人、帕坦人和马来裔穆斯林的清真寺。2011年,该市有16座清真寺。[37]

Two gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship), Siri Guru Singh Sabha and Namdhari,[38] serve the city’s Sikh community.[38]

参考译文:Siri Guru Singh Sabha 和 Namdhari 两个谒师所(锡克教礼拜场所)[38] 为该市的锡克教社区提供服务。[38]

The Hindu temple Dev Mandir serves the Hindu community.[38]

参考译文:印度教寺庙 Dev Mandir 为印度教社区服务。[38]

5. 管理 | Administration

The Administration of Chiang Mai Municipality is responsible for an area that covers approximately 40.216 square kilometers and consists of 4 Municipal Districts, 14 sub-districts, 94 municipal communities, and 89,656 households.[2]

参考译文:清迈市政府负责管理面积约40.216平方公里的地区,由4个区、14个分区、94个市辖区和89656户组成。 [2]

According to Municipal Act B.E. 2496 (1953, reviewed in 2003), the duties of the Municipality cover a lot of areas which include clean water supply, waste and sewage disposal, communicable disease control, public training and education, public hospitals and electricity, etc.[39]

参考译文:根据1953年颁布的B . E .2496号市政法(2003年修订) ,市政当局的职责涉及很多领域,包括清洁供水、废物和污水处理、传染病控制、公共培训和教育、公立医院和电力等。

The mayor, or the highest executive, is directly elected by the eligible voters in the municipal area. The mayor serves a four-year term and is assisted by no more than four deputy mayors appointed directly by the mayor. The mayor will thus be permitted to appoint deputies, secretaries and advisors including the mayor himself or herself totally no more than 10. The current Mayor is Tussanai Burabupakorn, as of June 2018.[39]

参考译文:市长是城市的最高行政长官,由市辖区的合格选民直接选举产生。市长任期四年,由不超过四名副市长协助工作,这些副市长由市长直接任命。因此,市长可以任命最多十名副手、秘书和顾问,包括市长本人。截至2018年6月,现任市长为Tussanai Burabupakorn。[39]

The Municipal Council is the legislative body of the municipality. It has the power to issue ordinances by laws that do not contradict with the laws of the country. The municipal council applies to all people living in the municipal area. The Chiang Mai City Municipal Council is composed of 24 elected members from 4 municipal districts who each serves a 4-year term.[39]

参考译文:市议会是该市的立法机构,有权根据法律发布法令,但这些法令不得与国家法律相抵触。市议会适用于居住在市区的所有居民。清迈市议会由来自4个市区的24名民选议员组成,每个议员任期为4年。[39]

6. 文化 | Culture

6.1 节庆 | Festivals

Chiang Mai hosts many Thai festivals, including:

参考译文:清迈举办许多泰国节日,包括:

Loi Krathong (along with Yi Peng), held on the full moon of the 12th month of the traditional Thai lunar calendar, being the full moon of the second month of the old Lanna calendar. In the Western calendar this usually falls in November. Every year thousands of people assemble floating banana-leaf containers (krathong) decorated with flowers and candles and deposit them on the waterways of the city in worship of the Goddess of Water. Lanna-style sky lanterns(khom fai or kom loi), which are hot-air balloons made of paper, are launched into the air. These sky lanterns are believed to help rid the locals of troubles and are also used to decorate houses and streets.

参考译文:水灯节(与蜡烛节齐名)在泰国传统阴历的12月满月之日举行,也就是旧兰纳日历的第二个月。在阳历中,这通常落在11月份。每年,成千上万的人聚集在一起,将装饰着鲜花和蜡烛的香蕉叶容器( krathong )投放到城市的水道上,以崇拜水神。兰纳风格的天灯( khom fai或kom loi )是用纸制成的热气球,被发射到空中。这些天灯被认为可以帮助当地人摆脱麻烦,也用于装饰房屋和街道。

Songkran is held in mid-April to celebrate the traditional Thai New Year. Chiang Mai has become one of the most popular locations to visit during this festival. A variety of religious and fun-related activities (notably the indiscriminate citywide water fight) take place each year, along with parades and Miss Songkran beauty competition.

参考译文:泼水节在4月中旬举行,庆祝泰国传统新年。清迈已成为节日期间最受欢迎的旅游地点之一。每年都会举办各种宗教和娱乐活动(特别是全市范围内的混战) ,以及游行和泼水节小姐选美比赛。

Chiang Mai Flower Festival is a three-day festival held during the first weekend in February each year; this event occurs when Chiang Mai’s temperate and tropical flowers are in full bloom.

参考译文:清迈花卉节是每年二月第一个周末举行的为期三天的节日; 这一活动发生在清迈的温带和热带花卉盛开之时。

Tam Bun Khan Dok, the Inthakhin (City Pillar) Festival, starts on the day of the waning moon of the sixth lunar month and lasts 6–8 days.

参考译文:Tam Bun Khan Dok,即 Inthakhin(城柱)节,从农历六月残月那天开始,持续 6 至 8 天。

Notable local Buddhist celebrations are Visakha Bucha Day at Doi Suthep (mountain) where thousands of Buddhists make the journey on foot after sunset, from the bottom of the mountain to the temple at the top Wat Doi Suthep.[40] Makha Bucha Day is celebrated at large temples (Wat Phra Singh, Wat Chedi Luang, Wat Phra That Doi Suthep, and Wat Sri Soda) with thousands of attendees.[41]

参考译文:泰国的佛教庆典在当地非常著名,其中最著名的是Doi Suthep(素贴山)的Visakha Bucha Day。在这个节日里,成千上万的佛教徒会在日落后从山脚下徒步前往山顶的Wat Doi Suthep寺庙。Makha Bucha Day则是在大型寺庙(如Wat Phra Singh、Wat Chedi Luang、Wat Phra That Doi Suthep和Wat Sri Soda)举行的庆典,吸引了数以千计的参与者。这些庆典是泰国佛教文化的重要组成部分,也是当地人民信仰和团结的象征。

6.2 语言 | Language

当地居民操北部泰语。用来撰写北部泰语的文字系统称为老傣文,但仅为学术研究和宗教之用,一般民众改以标准泰文字撰写。由于清迈观光业发达,旅馆和旅游业也会使用英文、中文和日文。

6.3 博物馆 | Museums

- Chiang Mai City Arts and Cultural Center

参考译文:清迈艺术文化中心 - Chiang Mai National Museum, which highlights the history of the region and the Kingdom of Lan Na.

参考译文:清迈国家博物馆,重点介绍该地区和兰纳王国的历史。 - Chiang Mai Philatelic Museum, showing the history of postage stamps and postal development of Thailand, especially of Chiang Mai.[43]

参考译文:清迈集邮博物馆,展示了泰国特别是清迈的邮票和邮政发展的历史。[43] - Highland People Discovery Museum, a showcase on the history of the local mountain tribes.

参考译文:高地人民探索博物馆,展示当地山地部落的历史。 - Mint Bureau of Chiang Mai or Sala Thanarak, Treasury Department, Ministry of Finance, Rajdamnern Road (one block from AUA Language Center). Has an old coin museum open to the public during business hours. The Lan Na Kingdom used leaf (or line) money made of brass and silver bubbles, also called “pig-mouth” money. The exact original technique of making pig-mouth money is still disputed, and because the silver is very thin and breakable, good pieces are now very rare.[44]

参考译文:清迈造币局或 Sala Thanarak、财政部、Rajdamnern 路(距 AUA 语言中心一街区)。 有一个古钱币博物馆,在营业时间向公众开放。 兰纳王国使用黄铜和银泡制成的叶(或线)钱,也称为“猪嘴”钱。 猪口钱的确切原始制作技术仍有争议,而且由于银质很薄且易碎,所以现在好的作品已经非常罕见了。 [44] - Bank of Thailand Museum

参考译文:泰国银行博物馆 - Northern Telecoms of Thailand Museum, housed in a former telephone exchange building, displaying the history and evolution of telecommunications in Northern Thailand.[45]

参考译文:泰国北部电信博物馆,位于一座前电话交换机大楼内,展示泰国北部电信的历史和演变。[45] - MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, a museum of contemporary art which opened in 2016.[46][47] It is one of only two museums of contemporary art in Thailand, with the other museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Bangkok, considered somewhat more conservative in tastes than MAIIAM.[47]

6.4 餐饮 | Dining

Khan tok is a century-old Lan Na Thai tradition[48] in Chiang Mai. It is an elaborate dinner or lunch offered by a host to guests at various ceremonies or parties, such as weddings, housewarmings, celebrations, novice ordinations, or funerals. It can also be held in connection with celebrations for specific buildings in a Thai temple and during Buddhist festivals such as Khao Pansa, Og Pansa, Loi Krathong, and Thai New Year (Songkran).

参考译文:Khan tok 是清迈具有百年历史的兰纳泰传统[48]。 这是主人在各种仪式或聚会上为客人提供的精心准备的晚餐或午餐,例如婚礼、乔迁典礼、庆典、新手祝圣或葬礼。 它还可以与泰国寺庙中特定建筑的庆祝活动以及佛教节日(如 Khao Pansa、Og Pansa、Loi Krathong 和泰国新年(宋干节))期间举行。

Khao soi is a Northern Thai noodle curry dish found mostly in Chiang Mai. Khao Soi is usually presented in a simple bowl, with fresh lime wedge, shallots, and pickled cabbage.[citation needed]

参考译文:Khao soi 是泰国北部的咖喱面条,主要产于清迈。 Khao Soi 通常放在一个简单的碗中,配有新鲜的酸橙角、青葱和泡菜。[需要引用]

6.5 景点

- 清迈古城:建于1296年的清迈古城,呈四方形,每边城界长约1.5公里,四边均由城墙和护城河包围着,现时城墙和护城河均保存良好。为防止古城景观受到破坏,清迈市政府于1990年禁止市区建筑高楼,并为护城河加建滤水设施。

- 清迈素贴山:素贴寺的平台(海拔1053米)[4],本可以把清迈市全景尽收眼底(但是由于近几年到了春天的耕种季节,农民们买不起肥料就烧山上的草木来肥沃土地,结果整个泰国北部都是烟雾缭绕,能见度极差PM2.5数值严重超标)。清迈皇后的旧宫,虽然不大但是里面鸟语花香,蝴蝶飞舞,异常漂亮。

- 清迈艺术文化中心:这座博物馆的建筑物建于1924年,有展示清迈的历史资料、清迈人古今生活、清迈佛教文化、农业及山地民族资料等。位于文化中心的正前方,是著名的三王雕像,三位对清迈有重大贡献的人物:兰甘亨大帝、孟莱王和南蒙王并立,常有当地人在雕像前烧香献花,以示尊敬。

- 夜市:清迈最热闹的地方,原只是昌康路(Chang Klan Road)的一群摊贩,因附近旅馆林立,得地利之便,现已成为固定上有棚架、路边摊贩云集的夜市,贩售各式各样的廉价品,每天晚上都有,从日落到晚间11点。各式水果如榴莲、椰青。大部分的当地特产都可在这儿买到,如木雕、漆器、银器、古董、香肠、各式服饰、水果和点心,昆虫食品一应俱全。

7. 教育 | Education

7.1 高等教育

Chiang Mai has several universities, including Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University, Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna, Payap University, Far Eastern University, and Maejo University, as well as numerous technical and teacher colleges. Chiang Mai University was the first government university established outside of Bangkok. Payap University was the first private institution in Thailand to be granted university status.

参考译文:清迈有几所大学,包括清迈大学、清迈拉贾巴大学、兰纳皇家理工大学、帕雅普大学、远东大学和梅州大学,以及许多技术和师范学院。清迈大学是曼谷以外建立的第一所政府大学。帕雅普大学是泰国第一个获得大学地位的私立机构。

- 清迈大学(Chiang Mai University)

- 私立西北大学(Payap University)

- 清迈皇家大学 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Chiang Mai Rajabhat University )

- 清迈湄州大学 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Maejo University)

- 北清迈大学 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(North-Chiang Mai University)

- (泰国)国家体育大学清迈校区 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Thailand National Sports University Chiang Mai Campus)

- The Far Eastern University (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

7.2 国际学校

International primary and secondary schools for foreign students include:

参考译文:招收外国学生的国际中小学包括:

- French School of the Far East, an institute for Asian studies, has a centre in Chiang Mai.[49]

参考译文:远东法国学校是一个亚洲研究机构,在清迈设有中心。[49] - NIS国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) (Nakornpayap International School NIS):课程美制。

- 普林国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Prem Tinsulanonda International School):课程全IB (PYP,MYP,DP,CP)。

- 清迈国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Chiang Mai International School):课程美制。

- 兰纳国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Lanna International School):课程英制。

- 格蕾丝国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Grace International School):课程美制,教会学校。

- 美国太平洋国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(American Pacific International School):课程美制、部分IB。

- 潘雅顿国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Panyaden International School):课程英制。

- 新加坡国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Singapore International School Chiangmai SISB):课程英语、泰语、中文语

- 德国基督教国际学校(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Christian German School Chiangmai):课程德制。

- Unity国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Unity Concord International School):课程美制。

- ABS(Ambassador Bilingual School) (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆):课程英泰双语

- 兰实大学双语实验学校清迈分校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(SBS – Satit Bilingual School of Rangsit University)课程:英泰双语。

- 华丽国际学校 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Varee International School):课程英制。

- Meritton british internation school:课程英制–英泰双语。

- 蒙特梭利 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Chiang Mai Montessori School):课程英制。

- Hana Christian国际幼儿园 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(Hana Christian International Kindergarten):课程美制。

- sunshine幼儿园 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(sunshine kindergarten school)

- Chiangmai Kiddee Daycare & Kindergarten

- VAREE

- NAPA Chiang Mai School

- Sarasas Witaed Chiang Mai School:泰英双语

8. 环境 | Environment

8.1 气候 | Climate

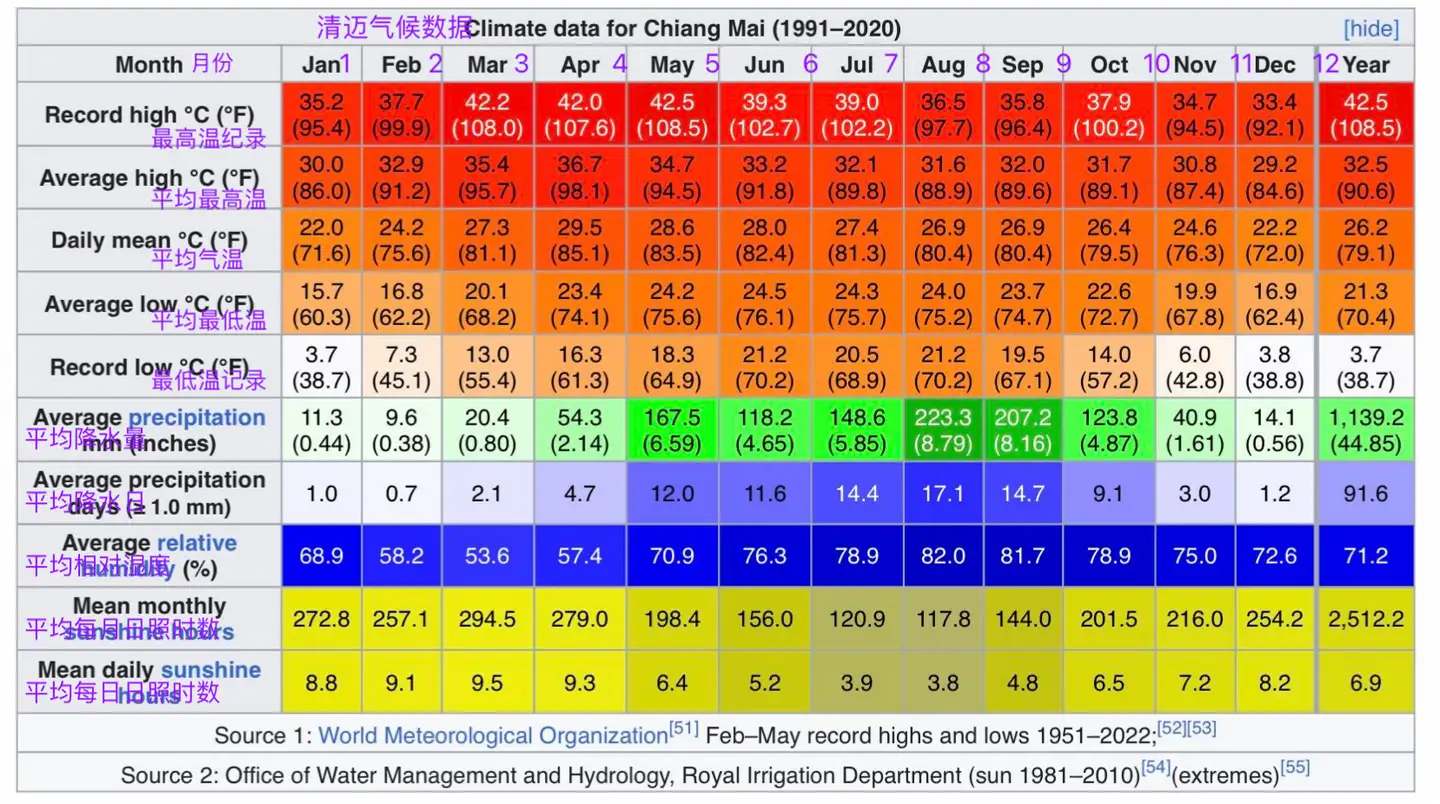

Chiang Mai has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw), tempered by the low latitude and moderate elevation, with warm to hot weather year-round, though nighttime conditions during the dry season can be cool and much lower than daytime highs. The maximum temperature ever recorded was 42.5 °C (108.5 °F) in May 2016. Cold and hot weather effects occur immediately but cold effects last longer than hot effects and contribute to higher cold related mortality risk among old people aged more than 85 years.[50]

参考译文:清迈属于热带草原气候(Köppen Aw),受低纬度和中等海拔的影响,全年温暖至炎热,尽管在旱季的夜间条件可能凉爽且远低于白天的最高温度。2016年5月记录到的最高气温为42.5°C(108.5°F)。寒冷和炎热天气的影响会立即出现,但寒冷的影响持续时间比炎热的影响更长,导致85岁以上老年人的寒冷相关死亡率风险更高。[50]

8.2 空气污染 | Air pollution

A continuing environmental issue in Chiang Mai is the incidence of air pollution that primarily occurs every year between December and April. In 1996, speaking at the Fourth International Network for Environmental Compliance and Enforcement conference—held in Chiang Mai that year—the Governor Virachai Naewboonien invited guest speaker Dr. Jakapan Wongburanawatt, Dean of the Social Science Faculty of Chiang Mai University, to discuss air pollution efforts in the region. Dr. Wongburanawatt stated that, in 1994, an increasing number of city residents attended hospitals suffering from respiratory problems associated with the city’s air pollution.[56]

参考译文:清迈持续的环境问题是每年12月至次年4月间发生的空气污染事件。1996年,在清迈举行的第四届国际环境合规与执法网络会议上,泰国政府官员Virachai Naewboonien邀请了清迈大学社会科学学院院长Jakapan Wongburanawatt博士作为嘉宾演讲,讨论该地区的空气污染问题。Wongburanawatt博士指出,1994年,越来越多的城市居民因呼吸系统疾病而就医,这些疾病与该市的空气污染有关。[56]

During the December–April period, air quality in Chiang Mai often remains below recommended standards, with fine-particle dust levels reaching twice the standard limits.[57] It has been said that smoke pollution has made March “the worst month to visit Chiang Mai”.[58]

参考译文:在12月至4月期间,清迈的空气质量经常低于推荐标准,细颗粒物水平达到标准的两倍。[57]据说烟雾污染使3月份成为“游览清迈最糟糕的月份”。[58]

According to the Bangkok Post, corporations in the agricultural sector, not farmers, are the biggest contributors to smoke pollution. The main source of the fires is forested areas being cleared to make room for new crops, primarily corn, which is rarely eaten in the local diet.

参考译文:据《曼谷邮报》报道,农业领域的企业,而非农民,是空气污染的最大贡献者。火灾的主要来源是被清理出来种植新作物的森林地区,主要是玉米,这种作物在当地的饮食中很少被食用。

“The true source of the haze… sits in the boardrooms of corporations eager to expand production and profits. A chart of Thailand’s growth in world corn markets can be overlaid on a chart of the number of fires. It is no longer acceptable to scapegoat hill tribes and slash-and-burn agriculture for the severe health and economic damage caused by this annual pollution.” These data have been ignored by the government. The end is not in sight, as the number of fires has increased every year for a decade, and data shows more pollution in late-February 2016 than in late-February 2015.[59]

参考译文:雾霾的真正源头在于那些渴望扩大生产和利润的公司董事会。泰国在世界玉米市场的增长图表可以与火灾数量的图表叠加在一起。不能再将严重的健康和经济损害归咎于山地部落和刀耕火种的农业,而忽视这些数据。政府一直忽视这些数据。随着火灾数量在过去十年中每年都在增加,情况并没有好转的迹象。数据显示,2016年2月下旬的污染比2015年2月下旬更严重。

The northern centre of the Meteorological Department has reported that low-pressure areas from China trap forest fire smoke in the mountains along the Thai-Myanmar border.[60] Research conducted between 2005 and 2009 showed that average PM10 rates in Chiang Mai during February and March were considerably above the country’s safety level of 120 μg/m³, peaking at 383 μg/m³ on 14 March 2007.[citation needed] PM2.5 rates (fine particles 75% smaller than PM10) reached 183 μg/m³ in Chiang Mai in 2018.[61] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the acceptable level of PM10 is 50 μg/m³ and PM2.5 is 25 μg/m³.[62]

参考译文:雾霾的真正源头在于那些渴望扩大生产和利润的公司董事会。泰国在世界玉米市场的增长图表可以与火灾数量的图表叠加在一起。不能再将严重的健康和经济损害归咎于山地部落和刀耕火种的农业,而忽视这些数据。政府一直忽视这些数据。随着火灾数量在过去十年中每年都在增加,情况并没有好转的迹象。数据显示,2016年2月下旬的污染比2015年2月下旬更严重。

To address the increasing amount of greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector in Chiang Mai, the city government has advocated the use of non-motorised transport (NMT). In addition to its potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the NMT initiative addresses other issues such as traffic congestion, air quality, income generation for the poor, and the long-term viability of the tourism industry.[63]

参考译文:为了解决清迈交通部门日益增长的温室气体排放量,市政府倡导使用非机动交通工具(NMT)。除了减少温室气体排放的潜力外, NMT倡议还解决了其他问题,如交通拥堵、空气质量、贫困人口创收和旅游业的长期可行性。[63]

8.3 对旅游业的影响 | Effects of tourism

The influx of tourists has put a strain on the city’s natural resources. Faced with rampant unplanned development, air and water pollution, waste management problems, and traffic congestion, the city has launched a non-motorised transport (NMT) system. The initiative, developed by a partnership of experts and with support from the Climate & Development Knowledge Network, aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and create employment opportunities for the urban poor. The climate compatible development strategy has gained support from policy-makers and citizens alike.[63]

参考译文:游客的涌入给城市的自然资源带来了压力。面对无序的发展规划、空气和水污染、废物管理问题以及交通拥堵,该市推出了非机动交通(NMT)系统。这一倡议由专家合作开发,并得到了气候与发展知识网络的支持,旨在减少温室气体排放并为城市贫困人口创造就业机会。这种气候兼容发展战略已经得到了政策制定者和市民的支持。[63]

See also: Environmental issues in Thailand

参考译文:参见:泰国的环境问题

9. 自然公园 | Nature

Nearby national parks include Doi Inthanon National Park, which includes Doi Inthanon, the highest mountain, and one of the most popular national parks in Thailand. It is famous for its waterfalls, few trails, remote villages, viewpoints, sunrise/sunset watching, bird watching, and the all year round cold weather on higher elevations.

参考译文:附近的国家公园包括茵他侬山国家公园,其中包括泰国最高的山峰——茵他侬山,也是泰国最受欢迎的国家公园之一。它以其瀑布、少有的小路、偏远的村庄、观景点、日出/日落观赏、鸟类观察以及全年高海拔地区的寒冷天气而闻名。

Doi Suthep–Pui National Park begins on the western edge of the city. Wat Doi Suthep Buddhist temple, located near the summit of Doi Suthep, can be seen from much of the city and its environs. In 2015, a development plan around the temple for a new housing project threatened to destroy some of the forest, but was halted, resulting in reforestation of the park.[64]

参考译文:素贴山—普尤国家公园位于城市的西缘。坐落在素贴山顶附近的素贴寺佛寺,可以从城市的大部分地方和周边地区看到。2015年,围绕寺庙的新住宅项目开发计划可能会破坏一些森林,但被叫停,导致公园重新造林。[64]

Pha Daeng National Park, or more commonly Chiang Dao National Park, which includes Doi Chiang Dao and Pha Deang mountain near the border with Myanmar.

参考译文:帕当国家公园,或更常被称为清佬国家公园,包括靠近缅甸边境的清佬山和帕当山。

Hill tribe tourism and trekking: Many tour companies offer organized treks among the local hills and forests on foot and on elephant back. Most also involve visits to various local hill tribes, including the Akha, Hmong, Karen, and Lisu.[65]

参考译文:山地部落旅游和徒步旅行:许多旅游公司提供有组织的徒步旅行,穿越当地的山丘和森林,有的还涉及参观各种当地山地部落,包括阿卡、苗族、克伦族和傈僳族。[65]

Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden

参考译文:诗丽吉王后植物园

Buatong waterfall (also called Sticky Waterfalls) – The formation of calcium lets you easily climb barefoot.

参考译文:Buatong 瀑布(也称为粘性瀑布)- 钙的形成让您可以赤脚轻松攀爬。

10. 娱乐 | Recreation

Chiang Mai Zoo, the oldest zoo in northern Thailand.

参考译文:清迈动物园,泰国北部最古老的动物园。

Shopping destinations: Chiang Mai has a large and famous night bazaar for local arts and handicrafts. The night markets extend across several city blocks along footpaths, inside buildings and temple grounds, and in open squares. A handicraft and food market opens every Sunday afternoon until late at night on Rachadamnoen Road, the main street in the historical centre, which is then closed to motorised traffic. Every Saturday evening a handicraft market is held along Wua Lai Road, Chiang Mai’s silver street[66] on the south side of the city beyond Chiang Mai Gate, which is then also closed to motorised traffic.[67]

参考译文:购物目的地:清迈有一个大型而著名的夜市,出售当地艺术品和手工艺品。夜市分布在几个城市街区的人行道上、建筑物内和寺庙场地以及开放广场上。每周日下午到深夜,在历史中心的主要街道拉差丹诺恩路上,会开设一个手工艺品和食品市场,该路段对机动车辆关闭。每周六晚上,在清迈门以南的城市南侧,沿着清迈的银街Wua Lai路举行手工艺品市场,该路段也对机动车辆关闭。

Shopping Malls: Besides Bangkok, until recently, Chiang Mai offered the most Big-Brand shopping malls. As of now there are three shopping malls operating in Chiang Mai: Central Chiang Mai Airport, Central Chiang Mai and Maya Shopping Mall. Two well known malls, Promenada and Kad Suan Kaew, had to close permanently in 2022 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic causing low foot-traffic and lower spending by visitors[citation needed].

参考译文:购物中心:除了曼谷,直到最近,清迈还提供了最多的大型品牌购物中心。目前,清迈有三个购物中心正在运营:清迈市中心机场、清迈市中心和玛雅购物中心。由于COVID-19大流行导致游客流量减少和消费降低,两个著名的购物中心Promenada和Kad Suan Kaew不得不在2022年永久关闭[需要引用]。

Thai massage: The back streets and main thoroughfares of Chiang Mai have many massageparlours which offer anything from quick, simple, face and foot massages, to month-long courses in the art of Thai massage.

参考译文:泰式按摩:清迈的背街和主要街道上有许多按摩院,提供从快速、简单的面部和足部按摩到为期一个月的泰式按摩艺术课程。

Thai cookery: A number of Thai cooking schools have their home in Chiang Mai.

参考译文:泰式烹饪:许多泰式烹饪学校都设在清迈。

For IT shopping, Pantip Plaza just south of Night Bazaar (few shops open due to COVID-19 pandemic), as well as Computer Plaza, Computer City, and Icon Square near the northwestern moat corner.

参考译文:对于IT购物,南面的Night Bazaar(由于COVID-19大流行,只有少数商店营业),以及西北护城河角附近的电脑广场、电脑城和Icon Square。

Horse racing: Every Saturday starting at 12:30 there are races at Kawila Race Track. Betting is legal.

参考译文:赛马: 每周六 12:30 在卡维拉赛马场 (Kawila Race Track) 举行比赛。 投注是合法的。

Chiang Mai is also to be the place where new idol group CGM48 founded.[68]

参考译文:清迈也将成为新偶像团体CGM48的创立地。[68]

Buak Hat Public Park: Located in the south west corner of the Old City.

参考译文:Buak Hat 公共公园:位于老城区的西南角。

Ang Keaw Reservoir: Located near the northern entrance to Chiang Mai University.

参考译文:Ang Keaw水库:位于清迈大学北入口附近。

11. 健康 | Health

The largest hospital in Chiang Mai City is Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, run by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. The Ministry of Public Health does not operate any hospitals in Chiang Mai City, with the closest one Nakornping Hospital, a regional hospital in Mae Rim District and is the MOPH’s largest hospital in the province.

参考译文:清迈市最大的医院是清迈大学医学院运营的Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital。公共卫生部在清迈市没有经营任何医院,最近的一家是位于湄林县的区域医院Nakornping Hospital,也是该省公共卫生部最大的医院。

Further information on the home for demented patients: Baan Kamlangchay

参考译文:有关痴呆症患者之家的更多信息:Baan Kamlangchay

12. 交通 | Transportation

12.1 航空

清迈国际机场位于清迈市中心西南面约4公里处,是泰国第四大国际机场,国内线航班有飞往曼谷、合艾、苏梅岛、喀比、普吉岛、素拉塔尼以及清莱、华欣、孔敬、派岛、彭世洛、眉宏顺、楠府、乌汶,每日有数十个航班往来首都曼谷,为进出泰北地区的门户。此外也有国际航班直接飞往新加坡、日本、香港、中国大陆、韩国、台湾等邻近亚洲国家。

Chiang Mai International Airport receives an average of 50 flights a day from Bangkok (25 from Suvarnabhumi and also 25 from Don Mueang,[69] flight time about 1 hour 10 minutes) and also serves as a local hub for services to other northern cities such as Chiang Rai, Phrae, and Mae Hong Son. International services also connect Chiang Mai with other regional centers, including cities in other Asian countries.

参考译文:清迈国际机场每天平均有50个航班从曼谷起飞(25个来自Suvarnabhumi,还有25个来自Don Mueang,[69]飞行时间约为1小时10分钟),并作为前往其他北部城市如清莱、帕府和湄宏顺的本地枢纽。国际服务还将清迈与亚洲其他国家的其他区域中心连接起来。

12.2 城际交通:铁路和大巴

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

有火车铁路贯通清迈和南面的曼谷、及北部的市镇(但是火车速度比较慢)。中国计划将滇南铁路自云南昆明南下出境,其中一个方案是接连清迈市。

The state railway operates 10 trains a day to Chiang Mai railway station from Bangkok. Most journeys run overnight and take approximately 12–15 hours. Most trains offer first-class (private cabins) and second-class (seats fold out to make sleeping berths) service. Chiang Mai is the northern terminus of the Thai railway system.

参考译文:国家铁路公司每天从曼谷发出10趟列车前往清迈火车站。大多数旅程在夜间进行,大约需要12-15小时。大多数列车提供头等舱(私人舱)和二等舱(座位可折叠成卧铺)服务。清迈是泰国铁路系统的北部终点站。

A number of bus stations link the city to central, southeast, and northern Thailand. The central Chang Puak Terminal (north of Chiang Puak Gate) provides local services within Chiang Mai Province. The Chiang Mai Arcade bus terminal northeast of the city centre (which can be reached with a songthaew or tuk-tuk ride) provides services to over 20 other destinations in Thailand including Bangkok, Pattaya, Hua Hin, and Phuket. There are several services a day from Chiang Mai Arcade terminal to Mo Chit Station in Bangkok (a 10- to 12-hour journey).

参考译文:许多巴士站连接着城市与泰国中部、东南部和北部。位于清迈门北边的清迈中央巴士总站(Chang Puak Terminal)提供清迈省内的本地服务。位于市中心东北方向的清迈购物中心巴士总站(Chiang Mai Arcade bus terminal)可乘坐songthaew或tuk-tuk前往,提供前往泰国20多个目的地的服务,包括曼谷、芭堤雅、华欣和普吉岛。每天从清迈购物中心巴士总站到曼谷Mo Chit车站有多趟班车(10至12小时车程)。

12.3 市内交通

清迈市主要靠以下几种交通工具:

- 计程车:泰北地区只有清迈市内看到有跳表的计程车,该类计程车可以按距离而收费,或可以在上车前和司机议好车资。但此类出租车数量较少,且主要在机场和长途汽车站运营,古城内一般没有出租车。从机场搭车到古城约120-150铢。

- 双排车或称双条车:亦称作宋条,是泰北最常见的交通工具,车身以枣红色为主色,由于车后面有一载客车厢,左右各有两排长条形的座椅,故称为双排车,因其发音越来越多人称其为双条车,运作形式介乎巴士与计程车之间:双排车无运行固定路线,按照距离长短收费,乘客只要扬手示意便可随时上车,亦可向司机议价或包车。古城附近一般20铢/人,从汽车站到古城约40泰铢/人。

- 嘟嘟车:亦称突突,属改装机车,一般是三轮机车,通常只在市内作短程行驶,价格比出租车和双条车便宜,需议价。最多只能坐4个人(2人最舒适)。

- 摩托计程车:由一位摩托车司机载一位乘客,需要议价。

- 租摩托车:自助游清迈最佳的出行方式就是借摩托车,大多为125cc排气量,24小时200铢,自己去加油。驾车时一定要戴安全帽,最好随身携带驾照(中华人民共和国驾照不被泰国承认)。

- 租自行车:租一辆自行车在清迈古城内漫游不失为一个轻松自由的好办法,非常惬意,租赁自行车约50铢/天,城内到处可见租车的地方,有些旅馆还会有出租自行车的服务。

- 公共巴士:R1 绿/紫线:清迈动物园─ Central Festival─清迈动物园沿途一共设置38站,费用30泰铢(时间:6:00~21:15);R2 红/黄线:Promenada─Promenada沿途一共设置52站,费用30泰铢(周一到周五时间:6:00~19:30);R3 机场─机场(环城观光线路)沿途一共设置44站费用30泰铢(时间6:00-23:30)。

- 自驾租车:可以提前在网上预约自驾租车服务(很多租车公司网上可供选择)在机场可取还1,500泰铢/日起,油费自理。

As population density continues to grow, greater pressure is placed upon the city’s transportation system. During peak hours, the road traffic is often badly congested. The city officials as well as researchers and experts have been trying to find feasible solutions to tackle the city’s traffic problems. Most of them agree that factors such as lack of public transport, increasing number of motor vehicles, inefficient land use plan and urban sprawl, have led to these problems.[72]

参考译文:随着人口密度的不断增加,城市交通系统面临着更大的压力。在高峰时段,道路交通往往严重拥堵。市政府官员、研究人员和专家一直在努力寻找可行的解决方案来解决城市的交通问题。他们大多数人认为,缺乏公共交通、机动车数量增加、土地利用效率低下以及城市扩张等因素导致了这些问题。[72]

The latest development is that Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (MRTA) has approved a draft decree on the light railway transitsystem project in Chiang Mai. If the draft is approved by the Thai cabinet, the construction could begin in 2020 and be completed by 2027.[73] It is believed that such a system would mitigate Chiang Mai’s traffic problems[74] to a large degree.

参考译文:最新进展是,泰国大众捷运局(MRTA)已批准了清迈轻轨交通系统项目的法令草案。如果该草案得到泰国内阁的批准,建设将于2020年开始,并于2027年完成。人们相信这样的系统将在很大程度上缓解清迈的交通问题。

13. “智慧城市”倡议 | “Smart City” initiative

In February 2017, the Digital Economy Promotion Agency (DEPA) (under Thailand’s Digital Economy and Society Ministry) announced that 36.5 million baht would be invested into developing Chiang Mai into an innovation-driven “smart city”. Chiang Mai was the second city in Thailand, after Phuket and along with Khon Kaen,[75] to be developed using the “smart city” model. The model aims to capture and populate multiple levels of information (including building, social, environmental, governmental, and economic data) from sources like sensors, real-time traffic information, and social forums for access by managers, governments, and citizens using mobile apps, tablets, and dashboards.[76] The “Smart City” outlook (integrating Information and Communications Technology (ICT) with the Internet of Things (IOT)), is viewed to be critical both for secondary cities with burgeoning urban population like Chiang Mai,[77] as well as part of Thailand’s move to be digital hub of ASEAN.[78]

参考译文:2017年2月,数字经济促进局(DEPA)(隶属于泰国数字经济和社会部)宣布将投资3650万泰铢用于将清迈发展成为创新驱动的“智能城市”。清迈是继普吉岛之后,泰国第二个使用“智能城市”模式进行发展的城市,与孔敬一起。该模式旨在从传感器、实时交通信息和社会论坛等来源收集和填充多个级别的信息(包括建筑、社会、环境、政府和经济数据),供管理人员、政府和公民使用移动应用程序、平板电脑和仪表板访问。智能城市前景(将信息通信技术(ICT)与物联网(IoT)相结合)对于像清迈这样人口迅速增长的二线城市至关重要,也是泰国成为东盟数字枢纽的一部分。

The role of private sector investment, together with public sector partnership, is key to promote digital entrepreneurship. Prosoft Comtech, a Thai software company, has spent 300 million baht to build its own “Oon IT Valley”[79] on a 90 rai plot of land as a community for tech start-ups, Internet of Things technology, software programmers and business process outsourcing services. It is aimed to both increase the size of Chiang Mai’s digital workforce, as well as attract foreign digital talent to Chiang Mai.[80]

参考译文:私营部门投资与公共部门合作在促进数字创业方面发挥着关键作用。泰国软件公司Prosoft Comtech投资3亿泰铢在其90 rai的土地上建立了自己的“Oon IT Valley”[79],作为一个科技初创企业、物联网技术、软件开发人员和业务流程外包服务的社区。其旨在增加清迈的数字劳动力规模,同时吸引外国数字人才来到清迈。[80]

13.1 智慧交通 | Smart transportation

In January 2018, it was announced that Chiang Mai would be launching “Mobike In,” a bike-sharing app that would see the introduction of some 500 smart bikes on the streets. The smart bikes would be available for use for both locals and tourists. It is reported that as a start, the bikes would be placed at convenient locations including the Three Kings monument, Tha Pae Gate and Suan Buak Haad Park, as well as in the old town. The “Mobike In” project is sponsored by Advanced Info Service (Thailand’s largest mobile phone operator), in collaboration with the Tourism Authority of Thailand (Chiang Mai Office), together with local universities, public and private sectors. The project aims to promote non-motorised transportation and support eco-tourism. Speaking at the launch at the Lanna Folklife Museum, Deputy Governor Puttipong Sirimart stated that the introduction of such “smart transportation” was a positive move in Chiang Mai’s transformation into a “Smart City” (part of the “Thailand 4.0” vision).[81]

参考译文:2018年1月,清迈宣布推出“Mobike In”共享单车应用程序,将在街头投放约500辆智能自行车。这些智能自行车将供当地居民和游客使用。据报道,作为起点,这些自行车将被放置在方便的位置,包括三王纪念碑、塔佩门和苏安布哈公园以及老城区。 “Mobike In”项目由泰国最大的移动电话运营商Advanced Info Service(泰国领先的电信运营商)与泰国旅游局(清迈办事处)以及当地大学、公共和私营部门合作赞助。该项目旨在推广非机动交通并支持生态旅游。在兰纳民俗博物馆的发布会上,副省长普提朋·西里马特表示,引入这种“智能交通”是清迈向“智能城市”(泰国4.0愿景的一部分)转型的积极举措。

13.2 智慧农业 | Smart agriculture

Phongsak Ariyajitphaisal, DEPA’s Chiang Mai branch manager, stated that one of the areas its smart city initiative would be promoting was “smart agriculture”. Eighty percent of Chiang Mai Province’s population are farmers, mostly small-scale, and increasing productivity through use of ICT has the potential to improve the local economy and living standards.[citation needed] DEPA has also provided funding to Chiang Mai’s Maejo University, to develop wireless sensor systems for better farmland irrigation techniques, to reduce use of water sprinklers and increase productivity. The university is also developing agricultural drones that can spray fertilizers and pesticides on crops which, if successful, will result in lower costs. The drones may also detect and monitor fires and smoke pollution.[80]

参考译文:泰国电子发展局清迈分局局长Phongsak Ariyajitphaisal表示,其泰国电子发展局清迈分局局长Phongsak Ariyajitphaisal表示,其智能城市倡议将推动的一个领域是“智能农业”。清迈省80%的人口是农民,主要是小规模的,通过使用信息通信技术提高生产力,有可能改善当地经济和生活水平。[需要引用]泰国电子发展局还为清迈梅州大学提供资金,以开发无线传感器系统,用于改进农田灌溉技术,减少喷水器的使用并提高生产力。该大学还在开发农业无人机,可以在作物上喷洒肥料和杀虫剂,如果成功的话,将降低成本。这些无人机还可以检测和监测火灾和烟雾污染。[80]

Under the 2011 IBM “Smarter Cities Challenge,” IBM experts recommended smarter food initiatives focused on creating agricultural data for farmers, including price modelling, farmer-focused weather forecasting tools, an e-portal to help farmers align crop production with demand, as well as branding of Chiang Mai produce. Longer-term recommendations included implementing traceability, enabling the tracking of produce from farm to consumer, smarter irrigation as well as flood control and early warning systems.[82]

参考译文:在2011年IBM的”智能城市挑战赛”下,IBM专家建议采取更智能的食品举措,重点关注为农民创建农业数据,包括价格建模、以农民为中心的天气预报工具、帮助农民调整作物生产的电子门户以及清迈农产品的品牌化。长期建议包括实施可追溯性,实现从农场到消费者的农产品追踪,更智能的灌溉以及洪水控制和预警系统。[82]

13.3 智慧医疗 | Smart healthcare

As part of the smart city project supported by IBM, Chiang Mai is also looking to use technology to boost its presence as a medical tourism hub. In 2011, IBM launched its Smarter Cities Challenge, a three-year, 100 city, 1.6 billion baht (US$50 million) program where teams of experts study and make detailed recommendations to address local important urban issues. Chiang Mai won a grant of about US$400,000 in 2011. The IBM team focused on smarter healthcare initiatives, aimed at making Chiang Mai and the University Medical Clinic a medical hub,[83] as well as improving efficiency of hospitals for improved service delivery. For example, healthcare providers could use real-time location tracking of patients and hospital assets to increase efficiency and build an internationally recognised service identity. Electronic medical record technology can also be adopted to standardise information exchanges to link all medical service providers, even including traditional medicine and spas.[84] Similar ideas include linking patient databases and healthcare asset information.[85] In partnership with the Faculty of Medicine at Chiang Mai University, the team of experts aim to enhance the quality of medical care available to the community, both urban and rural, as well as develop Chiang Mai into a centre for medical tourism with the infrastructure for supporting international visitors seeking long-term medical care.[86]

参考译文:作为IBM支持的智能城市项目的一部分,清迈还希望通过技术提升其作为医疗旅游中心的地位。2011年,IBM推出了Smarter Cities Challenge,这是一个为期三年、投资16亿泰铢(约合5000万美元)的项目,由专家团队研究并提出详细的建议,以解决当地重要的城市问题。清迈在2011年获得了约40万美元的拨款。IBM团队专注于更智能的医疗倡议,旨在使清迈和大学医疗诊所成为医疗中心,[83]并提高医院的效率,以改善服务交付。例如,医疗保健提供者可以使用实时定位追踪患者和医院资产,以提高效率并建立国际公认的服务身份。电子病历技术也可以采用,以标准化信息交换,连接所有医疗服务提供者,甚至包括传统医学和水疗中心。[84]类似的想法包括链接患者数据库和医疗资产信息。[85]与清迈大学医学院合作,专家团队旨在提高社区(无论是城市还是农村)可获得的医疗服务质量,以及将清迈发展成为医疗旅游中心,为寻求长期医疗护理的国际游客提供支持基础设施。[86]

As the largest city in northern Thailand, Chiang Mai already receives some long stay healthcare visitors, largely Japanese. Its main advantage over Bangkok is lower costs of living. Quality services at low prices are a major selling point in mainstream healthcare, dental and ophthalmologic care as well as Thai traditional medicine. Its local university is also developing specializations in robotic surgery and geriatric medicine to accommodate a future aging population.[84]

参考译文:作为泰国北部最大的城市,清迈已经吸引了一些长期医疗游客,主要是日本人。与曼谷相比,清迈的主要优势是生活成本较低。在主流医疗保健、牙科和眼科护理以及泰国传统医学方面,高质量服务和低价格是主要卖点。当地的大学也在开发机器人手术和老年医学专业,以适应未来的老龄化人口。[84]

13.4 智慧旅游业 | Smart tourism

DEPA also reported that it has developed a mobile app that uses augmented reality technology to showcase various historical attractions in Chiang Mai, in line with the government’s policy to promote Chiang Mai as a world heritage city.[80]

参考译文:泰国旅游局还报告称,它已经开发了一个使用增强现实技术的移动应用程序,以展示清迈的各种历史景点,这与政府将清迈作为世界遗产城市的政策相一致。[80]

14. 旅游业 | Tourism

According to Thailand’s Tourist Authority, in 2013 Chiang Mai had 14.1 million visitors: 4.6 million foreigners and 9.5 million Thais.[47] In 2016, tourist arrivals were expected to grow by approximately 10 percent to 9.1 million, with Chinese tourists increasing by seven percent to 750,000 and international arrivals by 10 percent to 2.6 million.[48] Tourism in Chiang Mai has been growing annually by 15 percent per year since 2011, mostly due to Chinese tourists who account for 30 percent of international arrivals.[48] In 2015, 7.4 million tourists visited Chiang Mai. Out of these, 35 percent were foreign tourists. The number of tourists has increased with an average rate of 13.6 percent annually between 2009 and 2015. The major reasons that have made Chiang Mai a tourist attraction are its topography, climate, and cultural history.[49] Chiang Mai is estimated to have 32,000–40,000 hotel rooms[47][48] and Chiang Mai International Airport (CNX) is Thailand’s fourth largest airport, after Suvarnabhumi (BKK), Don Mueang (DMK), and Phuket (HKT).[50]

【参考译文】根据泰国旅游局的数据,2013年清迈接待了1410万游客:460万外国游客和950万泰国游客。[47]预计2016年游客人数将增长约10%,达到910万人次,其中中国游客将增长7%,达到75万人次,国际游客将增长10%,达到260万人次。[48]自2011年以来,清迈的旅游业每年以15%的速度增长,这主要是由于中国游客的增长,他们占国际游客总数的30%。[48]2015年,740万游客访问了清迈。其中,35%为外国游客。游客数量以每年平均13.6%的速度增长,这一趋势从2009年持续到了2015年。使清迈成为一个旅游胜地的主要原因包括其地形、气候和文化历史。[49]据估计,清迈有3.2万至4万个酒店客房[47][48],清迈国际机场(CNX)是泰国第四大机场,仅次于素万那普机场(BKK)、廊曼机场(DMK)和普吉机场(HKT)。[50]

The Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau (TCEB) aims to market Chiang Mai as a global MICE city as part of a five-year plan. The TCEB forecasts revenue from MICE to rise by 10 percent to 4.24 billion baht in 2013 and the number of MICE travellers to rise by five percent to 72,424.[51]

【参考译文】泰国会议展览局(TCEB)计划在五年计划中将清迈推广为全球会展旅游城市。TCEB预计2013年会展旅游收入将增长10%,达到42.4亿泰铢,会展旅游人数将增长5%,达到72,424人。[51]

The Pacific Asia Travel Association, along with the Thai Government, is largely responsible for the development of tourism in Chiang Mai. Founded in 1951 and headquartered in Bangkok, Thailand, the Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA) is a non-profit membership association working to promote the responsible development of travel and tourism in the Asia Pacific region.

参考译文:太平洋亚洲旅游协会与泰国政府一起,对清迈旅游业的发展负有很大责任。该协会成立于1951年,总部设在泰国曼谷,是一个致力于促进亚太地区旅游业负责任发展的非营利会员协会。

From the beginning, Chiang Mai had the right ingredients for tourism – culture, climate, hotels, people, tours, scenery, power, roads, and services – which offered golden opportunities for extended visitor stays, a desired feature for successful tourism. What the city needed was some assistance in packaging these elements. This is where PATA came in.

参考译文:从一开始,清迈就具备了旅游业所需的各种条件,如文化、气候、酒店、人民、旅游线路、风景、基础设施、道路和服务等。这些条件为游客提供了延长停留的黄金机会,也是成功旅游业的理想特征。然而,这座城市所需要的是在这些元素之间进行协调和整合的帮助。这正是太平洋亚洲旅游协会(PATA)发挥作用的地方。

PATA first became involved in the development of tourism in Chiang Mai in 1968. PATA’s 9th Annual Workshop was held in 1968 and based in Chiang Mai, titled “Creating a New Destination”. The workshop provided an international forum for reviewing Chiang Mai’s tourism prospects while at the same time promoting it as a second Thai tourism destination other than Bangkok. In preparation for the Workshop, PATA sent an 11-member study team to Chiang Mai “to accomplish a study of the many decisions necessary to create a destination area of Chiang Mai, including an evaluation of the existing and natural assets, opportunities for development, community participation, financing, and the marketing of the product.”

参考译文:1968年,PATA首次参与清迈旅游业的发展。同年,PATA在清迈举办了第九届年度研讨会,主题为“打造新旅游目的地”。这次研讨会为国际人士提供了一个审视清迈旅游前景的平台,同时也将其作为泰国除曼谷之外的第二个旅游目的地进行推广。为了筹备这次研讨会,PATA派出了一个由11名成员组成的研究团队前往清迈,“对清迈作为一个旅游目的地所需做出的诸多决策进行研究,包括对现有和自然资产的评估、发展机会、社区参与、融资以及产品营销等方面。”

After the 1968 Chiang Mai workshop recommendations were implemented, the number of visitors to Chiang Mai rose dramatically. The increase, however, was largely attributed to the growth of regional, not international, traffic. In fact, between 1971 and 1973, Thai visitor counts increased 23% while international visitor counts decreased by 11%. The situation was reviewed by Thailand’s National Economic and Social Development Board’s Third National Plan (1972–76), and by both the United Nations Development Program and World Bank. Their investigations concluded that a study of Chiang Mai’s airport, which appeared to be over-congested, would provide answers to the discouraging numbers of international arrivals. As a result, Lieutenant General Chalermchai Charuvastr, Thai Army General and Founder/Director of the Tourist Organization of Thailand, contacted Marvin Plake with a request for sending a task force to Chiang Mai. The task force would introduce, plan, and implement a specific ‘idea’ regarding tourism development in Chiang Mai. The proposal was accepted at a PATA Development Authority meeting in Hawaii in August, 1974. With joint cooperation from the Thai Government and Thai Airlines, the mission commenced on January 27, 1975 with Cyril Herrmann, chairman of PATA’s Environmental, Social, and Economic Planning Committee, as a project leader.

参考译文:1968年清迈研讨会的建议实施后,清迈的游客数量急剧增加。然而,这种增长主要是由于区域交通的增长,而不是国际交通的增长。事实上,在1971年至1973年间,泰国游客数量增加了23%,而国际游客数量减少了11%。泰国国家经济和社会发展委员会的第三次国家计划(1972-76年)以及联合国开发计划署和世界银行都对此进行了审查。他们的调查得出结论,对清迈机场进行研究可能会提供关于令人沮丧的国际到达人数的答案,因为该机场似乎过于拥挤。因此,泰国陆军将军兼泰国旅游组织创始人/主任查勒姆柴·查鲁瓦斯特中将联系了马文·帕克,要求派遣一支特别工作组前往清迈。该工作组将引入、规划和实施有关清迈旅游业发展的特定“理念”。该提案于1974年8月在夏威夷举行的PATA发展局会议上获得通过。在泰国政府和泰国航空公司的联合合作下,该任务于1975年1月27日由PATA环境、社会和经济规划委员会主席西里尔·赫尔曼担任项目负责人启动。

Based on findings from the task force mission, PATA produced a report entitled “Creating a Destination Area.” The study noted that the use of land laws, zoning, open space, and architectural and design controls would help preserve Chiang Mai’s environmental and cultural character. In 1977, the Thailand Tourism Organization (TOT) asked the Development Authority to send a second task force to Chiang Mai. TOT wanted this team of experts to develop and recommend ways in which Chiang Mai could encourage more domestic and international air services. PATA initiated a two-week program: first, it would attempt to build up Chiang Mai’s regional traffic, and called upon members from regional airlines and tour operators for assistance; second, once airport operations had secured regional activity, expansion into the international market would then be targeted. The second task force determined that the international market was not adequately served – flight reservations in and out of Bangkok were difficult to make, and Thai Airways services were not well marketed overseas.

参考译文:根据任务组的调查结果,PATA发布了一份名为《打造目的地区域》的报告。报告指出,利用土地法、分区规划、开放空间以及建筑和设计控制将有助于保护清迈的环境和文化特色。1977年,泰国旅游局(TOT)要求发展局派遣第二个任务组前往清迈。TOT希望这个专家团队能够制定并推荐清迈如何鼓励更多的国内和国际航空服务。PATA启动了一个为期两周的计划:首先,它将尝试建立清迈的区域交通,并呼吁来自地区航空公司和旅行社的成员提供协助;其次,一旦机场运营确保了区域活动,就将目标扩大到国际市场。第二个任务组确定,国际市场没有得到充分满足-进出曼谷的航班预订很困难,而泰国航空公司的服务在海外市场推广不足。

As a result of the second investigation, the second task force produced “Chiang Mai, The Introduction of International Air Service,” a report containing both short-term plans and long-term recommendations to increase the amount of international tourists in Chiang Mai. These findings were submitted to TOT to help it establish a transportation policy to complement its tourism development program. The report concluded that Chiang Mai’s cultural image was highly marketable to foreign travelers, and needed to be promoted; that present accommodations were adequate and not restraining growth; and that as long as development and preservation were carefully balanced through sound planning, Chiang Mai’s capacity for tourism would continue to increase.

参考译文:作为第二次调查的结果,第二个工作组提出了《清迈国际航空服务介绍》的报告,其中包含了增加清迈国际游客数量的短期计划和长期建议。这些发现被提交给泰国旅游局(TOT),以帮助其制定一项补充其旅游发展计划的交通政策。报告得出结论,清迈的文化形象对外国游客具有高度吸引力,需要加以推广;目前的住宿条件是足够的,不会限制增长;只要通过合理的规划仔细平衡发展和保护,清迈的旅游接待能力将继续增加。

In the late 1970s, after receiving PATA’s task force recommendations via Tourist Organization of Thailand (TOT), the Thai government implemented a development plan based largely on PATA’s blueprint for Chiang Mai. These procedures could not have come at a better time, for the 1980s witnessed unprecedented visitor growth for Chiang Mai, turning tourism into the city’s most important economic activity. This increase spawned considerable expansion in other sectors as well, such as hotel, condominium, and golf course development. PATA’s involvement with Chiang Mai represented a milestone for comprehensive planning and development, and later proved to be one of PATA’s most remarkable achievements.

参考译文:20世纪70年代末,泰国政府通过泰国旅游局(TOT)收到了PATA工作组的建议后,实施了一项主要基于PATA对清迈的蓝图的发展计划。这些程序来得正是时候,因为20世纪80年代见证了清迈前所未有的游客增长,使旅游业成为该市最重要的经济活动。这种增长也促使其他领域的大量扩张,如酒店、公寓和高尔夫球场的开发。PATA与清迈的合作代表了全面规划和发展的一个里程碑,后来证明是PATA最杰出的成就之一。

According to Thailand’s Tourist Authority, in 2013 Chiang Mai had 14.1 million visitors: 4.6 million foreigners and 9.5 million Thais.[87] In 2016, tourist arrivals were expected to grow by approximately 10 percent to 9.1 million, with Chinese tourists increasing by seven percent to 750,000 and international arrivals by 10 percent to 2.6 million.[88] Tourism in Chiang Mai has been growing annually by 15 percent per year since 2011, mostly due to Chinese tourists who account for 30 percent of international arrivals.[88] In 2015, 7.4 million tourists visited Chiang Mai. Out of these, 35 percent were foreign tourists. The number of tourists has increased with an average rate of 13.6 percent annually between 2009 and 2015. The major reasons that have made Chiang Mai a tourist attraction are its topography, climate, and cultural history.[89]

参考译文:根据泰国旅游局的数据,2013年清迈接待了1410万游客:其中外国游客460万,泰国本土游客950万。[87] 2016年,预计游客数量将增长约10%,达到910万人,其中中国游客增长7%,达到75万人,国际游客增长10%,达到260万人。[88] 自2011年以来,清迈的旅游业每年以15%的速度增长,这主要得益于占国际游客30%的中国游客。[88] 2015年,有740万游客访问了清迈,其中35%是外国游客。从2009年到2015年,游客数量以平均每年13.6%的速度增长。使清迈成为旅游胜地的主要因素是其地形、气候和文化历史。[89]

Chiang Mai is estimated to have 32,000–40,000 hotel rooms[87][88] and Chiang Mai International Airport (CNX) is Thailand’s fourth largest airport, after Suvarnabhumi (BKK), Don Mueang (DMK), and Phuket (HKT).[90] Planning is underway for a second airport with a capacity to serve 10 million annual passengers.[91]

参考译文:清迈估计有32,000-40,000间酒店客房[87][88],而清迈国际机场(CNX)是泰国第四大机场,仅次于Suvarnabhumi(BKK)、Don Mueang(DMK)和普吉岛(HKT)。[90]正在规划建设第二个机场,其容量可满足1000万年度旅客的需求。[91]

The Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau (TCEB) aims to market Chiang Mai as a global MICE city as part of a five-year plan. The TCEB forecasts revenue from MICE to rise by 10 percent to 4.24 billion baht in 2013 and the number of MICE travellers to rise by five percent to 72,424.[92]

参考译文:泰国会议展览局( TCEB )旨在将清迈作为全球MICE城市进行市场推广,这是其五年计划的一部分。 TCEB预测2013年MICE收入将增长10%至42.4亿泰铢, MICE旅客人数将增长5%至72,424人。 [92]

Tourism has also brought benefits for the local community of Chiang Mai. For example, tourism has played a tremendous role in promoting arts and crafts market in Chiang Mai. Tourists have increased demand for traditional crafts and art forms that has resulted in the incentives for the local artists to enhance their work thus adding to the prosperity of the sector.[93] Moreover, there are great opportunities for agritourism in Chiang Mai. The factor analysis illustrates three types of agri needs, activities and shopping, facilities, services and location and the last one attractions and environment. Agritoursim is a type of business that a farmer conducts for additional farm income. Farmers, through the promotions of agricultural products, provide enjoyment and educate public about farming and agriculture.[94]

参考译文:旅游业也为清迈当地社区带来了好处。例如,旅游业在促进清迈的工艺美术市场方面发挥了巨大作用。游客对传统工艺品和艺术形式的需求增加,这激励了当地艺术家提高他们的工作水平,从而增加了该行业的繁荣。[93]此外,清迈还有很大的农业旅游机会。因素分析说明了三种类型的农业需求、活动和购物、设施、服务和位置以及最后一个景点和环境。农业旅游是农民为了增加农场收入而进行的一种商业活动。农民通过推广农产品,为公众提供乐趣并教育他们关于农业的知识。[94]

15. 知名人士 | Notable persons

- Marc Faber – investment analyst and entrepreneur

参考译文:Marc Faber – 投资分析师和企业家 - Jongkolphan Kititharakul – Thai badminton player, women’s doubles gold medalist at the 2017 Southeast Asian Games

参考译文:Jongkolphan Kititharakul – 泰国羽毛球运动员、2017 年东南亚运动会女子双打金牌获得者 - Anucha Saengchart – social media personality and cosplayer[95]

参考译文:Anucha Saengchart – 社交媒体个性和角色扮演者[95] - Rodjaraeg Wattanapanit – the first Thai winner of the International Women of Courage Award[96]

参考译文:Rodjaraeg Wattanapanit – 第一位荣获国际女性勇气奖的泰国人[96]

16. 友好城镇和姊妹城市 | Twin towns and sister cities

Chiang Mai has agreements with the following sister cities:[97]

参考译文:清迈与以下友好城市有协议:[97]

- Uozu, Japan (8 August 1989)

参考译文:日本鱼津(1989 年 8 月 8 日) - Saitama Prefecture, Japan (9 November 1992)

参考译文:日本埼玉县(1992 年 11 月 9 日) - Kunming, Yunnan, China (7 June 1999)

参考译文:中国昆明(1999年6月7日) - Harbin, China (29 April 2008)

参考译文:中国哈尔滨(2008年4月29日) - Pyongyang, North Korea[98]

参考译文:朝鲜平壤 - Da Lat, Lam Dong, Vietnam

参考译文:大叻, 林同省, 越南

18. 参见(相关维基百科词条)

- Buddhist temples in Chiang Mai(清迈的佛教寺庙)

- Chiang Mai Creative City(清迈创意城)

- Chiang Mai Initiative(清迈倡议)

- Royal Flora Ratchaphruek(拉差普鲁皇家植物园)

19. 参考文献

19.1 英文词条引用列表

- · [1],”พระราชบัญญัติจัดตั้งเทศบาลนครเชียงใหม่ พุทธศักราช ๒๔๗๘”

- · ^ Jump up to: a b “สถิติทางการทะเบียน” [Registration statistics]. bora.dopa.go.th. Department of Provincial Administration (DOPA). December 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2020. Download จำนวนประชากร ปี พ.ศ.2562 – Download population year 2019

- · ^ Jump up to: a b c “Chiang Mai, Thailand Metro Area Population 1950-2022, Data provided by the United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Population Division”. www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b “Department of Provincial Administration (DOPA), Population data for the year 2022”.

- · ^ “National Statistical Office Thailand – Population Data 2022”. statbbi.nso.go.th. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cœdès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of south-east Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai Night Bazaar in Chiang Mai Province, Thailand”. Lonely Planet. 2011-10-24. Archived from the original on 2012-08-06. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- · ^ “มหาวิทยาลัยนอร์ท-เชียงใหม่ [North – Chiang Mai University]”. Northcm.ac.th. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai Municipality” (in Thai). Chiang Mai City. 2008. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- · ^ Colquhoun, Archibald Ross (1885). Amongst the Shans. New York: Scribner & Welford. p. 121. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- · ^ Aroonrut Wichienkeeo (2001–2012). “Lawa (Lua) : A Study from Palm-Leaf Manuscripts and Stone Inscriptions”. COE Center of Excellence. Rajabhat Institute of Chiangmai. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 15 Aug 2012.

- · ^ See also the chronicle of Chiang Mai, Zinme Yazawin, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- · ^ “History of Chiang Mai – Lonely Planet Travel Information”. Lonelyplanet.com. 2006-09-19. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- · ^ “Thailand’s World: General Kavila”. Thailandsworld.com. 2012-05-06. Archived from the original on 2012-06-15. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- · ^ “พระราชบัญญัติ จัดตั้งเทศบาลนครเชียงใหม่ พุทธศักราช ๒๔๗๘”[Royal Decree Establishing Chiang Mai city municipality, Buddhist Era 2478 (1935)] (PDF). Royal Thai Government Gazette. 52: 2136–2141. 29 March 1935. Archived from the original (PDF)on November 10, 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2020, Area 17.5 sq.km.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b “พระราชกฤษฎีกา เปลี่ยนแปลงเขตเทศบาลนครเชียงใหม่ จังหวัดเชียงใหม่ พ.ศ. ๒๕๒๖” [Royal Decree Enlargement of Chiang Mai city municipality, Chiang Mai province, B.E.2526 (1983)] (PDF). Royal Thai Government Gazette. 100 (53): 4–10. 5 April 1983. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2020, 40.2 sq.km.

- · ^ S.T. Leng (October–November 2010). “TCEB keen on World Expo 2020”. Exhibition Now. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved 13 Jan 2013.

- · ^ Suchat Sritama (2011-04-05). “Ayutthaya Chosen Thailand’s Bid City for World Expo 2020”. The Nation (Thailand) Asia News Network. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 12 Dec 2012.

- · ^ “Best Destinations in the World; Travelers’ Choice Awards 2014”. TripAdvisor. Retrieved 2014-12-12.[failed verification]

- · ^ Jump up to: a b Chiang Mai Provincial Administrative Organization, Royal Gazette (May 21, 2013). “Ministerial Regulations that shall be incorporated into the Chiang Mai unified city plan, Page 32 (in Thai)” (PDF).

- · ^ “Ministerial Regulations to enforce the City plan, Chiang Mai Province (No. 2) B.E. 2559 – Regarding the official city plans by the Chiang Mai Provincial Administration” (PDF). Royal Gazette.

- · ^ “Chapter 3 – Current environmental resources, Khon Kaen University, Feasabilty study on Condominiums in the Chiang Mai Urban Area, Page 16+18” (PDF).

- · ^ “Gathering opinions to create a 4th Revision of the Chiang Mai City Plan”. Chiangmai News (In Thai).

- · ^ “Department of Public Works and Town & Country Planning – City Plan, Chiang Mai (4th Revision)”.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai City, Chiang Mai Municipality” (PDF).

- · ^ “Chiang Mai Municipality — Emblem”. Chiang Mai City. 2008. Archived from the original on June 30, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- · ^ “Lan Na Rebirth: Recently Re-established Temples”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW

- · ^ “Chiang Mai | Thailand”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- · ^ “Wat Phra Singh Woramahaviharn”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- · ^ ^ “Wat Chedi Luang: Temple of the Great Stupa”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- · ^ “Wat Ku Tao: Chang Phuak’s Watermelon Temple”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 1. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- · ^ “Wat Rampoeng Tapotharam” in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- · ^ “Wat Suan Dok, the Flower Garden temple”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW

- · ^ “Archaeological Site Database of the Sirindhorn Anthropology Center”, https://www.sac.or.th/databases/archaeology/archaeology?field_a_province_tid=14&title=&page=1

- · ^ “Churches”. Chiang Mai Info. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- · ^ “The Muslim Community Past and Present”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW

- · ^ “Muslim Chiangmai” (bi-lingual Thai-English) (in Thai). Muslim Chiangmai. September 21, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011. Samsudin Bin Abrahim is the Imam of Chang Klan Mosque in Chiang Mai and a vibrant personality within Chiang Mai’s 20,000 Muslim community

- · ^ Jump up to: a b c “Chiang Mai — A Complete Guide To Chiangmai”. Chiangmai-thai.com. 2008-07-06. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b c “Chiang Mai Municipality”.

- · ^ CityNews. “Visakha Bucha Day this Friday – Chiang Mai CityNews”. Chiang Mai Citylife. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- · ^ CityNews. “Thousands Celebrate Makha Bhucha Day in Chiang Mai – Chiang Mai CityNews”. Chiang Mai Citylife. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- · ^ See: Forbes, Andrew, “The Peoples of Chiang Mai”, in Penth, Hans, and Forbes, Andrew, A Brief History of Lan Na. Chiang Mai City Arts and Cultural Centre, Chiang Mai, 2004, pp. 221–256.

- · ^ Museums of Thailand website https://www.museumthailand.com/en/museum/Chiangmai-Philatelic-Museum-2

- · ^ “Thai Coins History”. Royal Thai Mint. 28 Mar 2010. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved 19 Sep 2011.

- · ^ Museums of Thailand website https://www.museumthailand.com/en/museum/Northern-Telecoms-of-Thailand-Museum

- · ^ MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum

- · ^ Jump up to: a b Chiang Mai: Adeline Chia checks out the city’s grassroots art scene

- · ^ “Khan Tok Dinner”. Lanna Food. Chiang Mai University Library. Archived from the original on 2020-07-20. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- · ^ “The Chiang Mai Centre, Thailand.” École française d’Extrême-Orient. Retrieved on 8 September 2018.

- · ^ Yuming Guo, Kornwipa Punnasiri and Shilu Tongly (9 July 2012). “Effects of temperature on mortality in Chiang Mai city, Thailand: A time series study”. Environmental Health. 11: 36. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-11-36. PMC 3391976. PMID 22613086.[permanent dead link]

- · ^ “World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020”. World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- · ^ Thai Meteorological Department. “สถิติอุณหภูมิสูงที่สุดในช่วงฤดูร้อนของประเทศไทยระหว่าง พ.ศ. 2494 – 2565” [Extreme maximum temperature during summer season in Thailand (1951 – 2022)] (PDF). TMD website. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- · ^ Thai Meteorological Department. “Extreme minimum temperature during winter season in Thailand 71 year period (1951 – 2021);” (PDF). TMD website. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- · ^ “ปริมาณการใช้น้ำของพืชอ้างอิงโดยวิธีของ Penman Monteith (Reference Crop Evapotranspiration by Penman Monteith)”(PDF) (in Thai). Office of Water Management and Hydrology, Royal Irrigation Department. p. 14. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- · ^ “Climatological Data for the Period 1981–2010”. Thai Meteorological Department. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai’s Environmental Challenges”, Fourth International Conference of Environmental Compliance and Enforcement

- · ^ “Air Pollution in Chiang Mai: Current Air Quality & PM-10 Levels”. Earthoria. 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- · ^ “Smoke Pollution Makes March the Worst Month to Visit Chiang Mai and Northern Thailand – Siam and Beyond”. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

- · ^ “Officials in a haze”. Bangkok Post. 2016-02-23. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai’s air pollution still high”. Nationmultimedia.com. 2007-03-11. Archived from the original on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai CityNews – Chiang Mai Records Highest PM2.5 Readings in the World, March 6, 2018”. www.chiangmaicitylife.com. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- · ^ “WHO Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide, Global Update 2005”(PDF). WHO. 2006. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b Kusakabe, Kyoko; Shrestha, Pujan; Kumar, S; Suwanprik, Trinnawat (May 2014). “Catalysing sustainable tourism: The case of Chiang Mai, Thailand” (PDF). Climate & Development Climate Network (CDKN). Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- · ^ EJOLT. “Housing project in Doi Suthep mountains, Thailand | EJAtlas”. Environmental Justice Atlas. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai’s Hill Peoples”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- · ^ “Shan Silversmiths of Wua Lai”, in Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai, Volume 4. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006J541LE

- · ^ Lonely Planet (2012). “Shopping in Chiang Mai”. Lonely Planet. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- · ^ “Fakta CGM48 Member Audisi” (in Indonesian). Shukan Bunshun. 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- · ^ “CHIANG MAI AIRPORT GUIDE”. www.chiangmaiairportonline.com. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- · ^ “เชียงใหม่เปิดตัวและแสดงข้อมูลระบบขนส่งสาธารณะ จับทุกภาคส่วนลงนามร่วมพัฒนาต่อเนื่อง”. Manager Online (in Thai). Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai CityNews – 450 Electric Tuk Tuks for Chiang mai Approved by DLT”. www.chiangmaicitylife.com. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- · ^ Peraphan, Jittrapirom; Hermann, Knoflacher; Markus, Mailer (2017-01-01). “Understanding decision makers’ perceptions of Chiang Mai city’s transport problems an application of Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) methodology”. Transportation Research Procedia. World Conference on Transport Research – WCTR 2016 Shanghai. 10–15 July 2016. 25 (Supplement C): 4438–4453. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2017.05.350.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai to Have Light Rail Transit by 2027”. Chiang Mai Citylife. 27 November 2018.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai for Digital Nomads”. Moving Nomads. Archived from the original on 2018-02-06. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- · ^ Boonnoon, Jirapan (2017-01-27). “DE Ministry pushing for nationwide”. The Nation. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ “Prayut gets long-distance look at ‘smart’ 3D Chiang Mai”. The Nation. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Da Hsuan, Feng; Hai Ming, Liang (28 September 2017). “Thailand can be smart-city flagship for Belt and Road”(Editorial). The Nation. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Asina Pornwasin (15 September 2015). “Plan to make Phuket and Chiang Mai ‘smart cities'”. The Nation. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ “Oon IT Valley ออนไอทีวัลเลย์ เมืองไอที วิถีล้านนา”. Oon IT Valley ออนไอทีวัลเลย์ เมืองไอที วิถีล้านนา (in Thai). Archived from the original on 2018-03-01. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b c Leesa-Nguansuk, Suchit (11 February 2017). “Chiang Mai to become smart city”. Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai To Get 500 Smart Bikes, Known as MOBIKE IN”. Citylife Chiang Mai. 2018-01-19. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ “Chiang Mai Summary Report” (PDF). IBM Smarter Cities Challenge. 2011. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Sambandaraksa, Don (22 September 2010). “IBM focuses on Chiang Mai”. Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b “Smarter technology: medical tourism in Thailand”. International Medical Travel Journal (IMTJ). 2 June 2011. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Leesa-Nguansuk, Suchit (1 August 2016). “A tale of smart cities”. Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Boonnoon, Jirapan (19 July 2012). “Thai arm of IBM spreads wings in Laos”. The Nation. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b “Internal Tourism in Chiang Mai” (PDF). Thailand Department of Tourism. Department of Tourism. 2014-08-20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-29. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- · ^ Jump up to: a b c Chinmaneevong, Chadamas (2016-05-21). “Chiang Mai hoteliers face price war woe”. Bangkok Post. Retrieved 22 May2016.

- · ^ Pardthaisong, Liwa (29 December 2017). “Haze Pollution in Chiang Mai, Thailand: A Road to Resilience”. Procedia Engineering Volume 212, 2018, Pages 85-92. Archived from the original on July 3, 2021. Retrieved 22 Feb 2018.

- · ^ “2013 (Statistic Report 2013)”. About AOT: Air Transport Statistic. Airports of Thailand PLC. Archived from the original on 2014-12-07. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- · ^ “» Second airports slated for Phuket and Chiang Mai”. thaiembdc.org. Retrieved 2018-12-12.