中文词条原链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。文中部分字词采用拼音表示,其中数字表示声调,读音以中国内地普通话为准。

关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及其他已搬运的词条,请点击这里了解更多。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

目录

- 0. 概述

- 1. 目标 | Aims

- 2. 发展历程 | Development

- 3. 缔约方 | Parties

- 4. 内容 | Content

- 5. 特定关注议题 | Specific topics of concern

- 6. 实施 | Implementation

- 7. 收效与争论 | Reception and debates

- 2. 参见 See also(维基百科的相关词条)

0. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

The Paris Agreement (French: Accord de Paris), often referred to as the Paris Accords or the Paris Climate Accords, is an international treaty on climate change. Adopted in 2015, the agreement covers climate change mitigation, adaptation, and finance. The Paris Agreement was negotiated by 196 parties at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference near Paris, France. As of February 2023, 195 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are parties to the agreement. Of the three UNFCCC member states which have not ratified the agreement, the only major emitter is Iran. The United States withdrew from the agreement in 2020, but rejoined in 2021.

【参考译文】巴黎协定(法语:Accord de Paris),通常称为巴黎协议或巴黎气候协定,是一项关于气候变化的国际条约。该协定于2015年通过,涵盖了气候变化减缓、适应和融资等方面。巴黎协定由196个缔约方在2015年法国巴黎附近的联合国气候变化大会上谈判达成。截至2023年2月,联合国气候变化框架公约(UNFCCC)的195个成员国加入了该协定。在尚未批准该协定的三个UNFCCC成员国中,唯一主要的排放国是伊朗。美国在2020年退出了该协定,但在2021年重新加入。

The Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal is to keep the rise in mean global temperature to well below 2 °C (3.6 °F) above pre-industrial levels, and preferably limit the increase to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), recognizing that this would substantially reduce the effects of climate change. To achieve this goal, emissions should be reduced as soon as possible and reach net zero by the middle of the 21st century.[3] To stay below 1.5 °C of global warming, emissions need to be cut by roughly 50% by 2030. This is an aggregate of each country’s nationally determined contributions.[4]

【参考译文】巴黎协定的长期温度目标是将全球平均温度的上升幅度控制在远低于工业化前水平以上的2摄氏度(3.6华氏度)以内,并争取将增温限制在1.5摄氏度(2.7华氏度)以内,认识到这将大幅减少气候变化的影响。为了实现这一目标,应尽快减少排放,并在21世纪中叶实现净零排放。[3] 为了将全球变暖控制在1.5摄氏度以下,到2030年排放量需要削减大约50%。这是各国国家自定贡献的总和。[4]

It aims to help countries adapt to climate change effects, and mobilize enough finance. Under the agreement, each country must determine, plan, and regularly report on its contributions. No mechanism forces a country to set specific emissions targets, but each target should go beyond previous targets. In contrast to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the distinction between developed and developing countries is blurred, so that the latter also have to submit plans for emission reductions.

【参考译文】它旨在帮助各国适应气候变化的影响,并动员足够的资金。根据该协定,每个国家必须确定、规划并定期报告其贡献。没有机制强制一个国家设定具体的排放目标,但每个目标应超越之前的目标。与1997年的京都议定书相比,发达国家和发展中国家之间的区别变得模糊,以至于后者也必须提交减排计划。

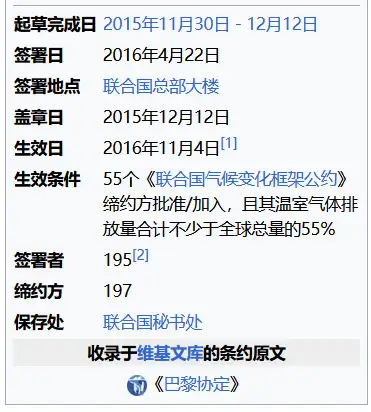

The Paris Agreement was opened for signature on 22 April 2016 (Earth Day) at a ceremony inside the UN Headquarters in New York. After the European Union ratified the agreement, sufficient countries had ratified the agreement responsible for enough of the world’s greenhouse gases for the agreement to enter into force on 4 November 2016.

【参考译文】巴黎协定于2016年4月22日(地球日)在纽约联合国总部内的仪式上开放签署。在欧盟批准该协定后,足够数量的国家批准了该协定,这些国家负责世界上足够的温室气体排放量,使得该协定于2016年11月4日生效。

The agreement was lauded by world leaders, but criticized as insufficiently binding by some environmentalists and analysts. There is debate about the effectiveness of the agreement. While current pledges under the Paris Agreement are insufficient for reaching the set temperature goals, there is a mechanism of increased ambition. The Paris Agreement has been successfully used in climate litigation forcing countries and an oil company to strengthen climate action.[5][6]

【参考译文】世界领导人对这项协议表示赞赏,但一些环保人士和分析人士批评它的约束力不够。对于协议的效力存在争议。尽管《巴黎协定》下的当前承诺不足以实现设定的温度目标,但存在一种增加雄心的机制。《巴黎协定》已成功在气候诉讼中被使用,迫使各国和一家石油公司加强气候行动。

1. 目标 | Aims

The aim of the agreement, as described in Article 2, is to have a stronger response to the danger of climate change; it seeks to enhance the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change through:[7]

【参考译文】该协议的目标,如第2条所述,是对抗气候变化的危险采取更强有力的应对措施;它寻求通过以下方式加强《联合国气候变化框架公约》的实施:[7]

(a) Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;

【参考译文】(a) 控制全球平均气温的升高,使其远低于工业化前水平之上的2摄氏度,并努力将气温升高限制在工业化前水平之上的1.5摄氏度以内,认识到这将显著减少气候变化的风险和影响;(b) Increasing the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development, in a manner that does not threaten food production;

【参考译文】(b) 提升适应气候变化不利影响的能力,并促进气候韧性及低碳温室气体排放的发展,同时不威胁粮食生产;(c) Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

【参考译文】(c) 使金融流动与低温室气体排放和气候韧性发展的道路保持一致。

Countries furthermore aim to reach “global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible.”[7]

【参考译文】各国还致力于“尽快实现全球温室气体排放的峰值。”[7]

2. 发展历程 | Development

2.1 准备阶段 | Lead-up

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted at the 1992 Earth Summit is one of the first international treaties on the topic. It stipulates that parties should meet regularly to address climate change, at the Conference of Parties or COP. It forms the foundation to future climate agreements.[8]

【参考译文】联合国气候变化框架公约(UNFCCC),是在1992年地球峰会上通过的,它是关于这一主题的首批国际条约之一。它规定缔约方应定期在缔约方会议或COP上会晤,以应对气候变化。它为未来的气候协议奠定了基础。[8]

The Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997, regulated greenhouse gas reductions for a limited set of countries from 2008 to 2012. The protocol was extended until 2020 with the Doha Amendment in 2012.[9] The United States decided not to ratify the Protocol, mainly because of its legally-binding nature. This, and distributional conflict, led to failures of subsequent international climate negotiations. The 2009 negotiations were intended to produce a successor treaty of Kyoto, but the negotiations collapsed and the resulting Copenhagen Accord was not legally binding and did not get adopted universally.[10][11]

【参考译文】京都议定书于1997年通过,规定了从2008年到2012年对有限国家进行温室气体减排。该议定书在2012年的多哈修正案中被延长至2020年。[9] 美国决定不批准该议定书,主要是因为它的法律约束性质。这以及分配上的冲突导致后续国际气候谈判的失败。2009年的谈判旨在产生一个继京都之后的后续条约,但谈判崩溃,结果产生的哥本哈根协议没有法律约束力,且未被普遍采纳。[10][11]

The Accord did lay the framework for bottom-up approach of the Paris Agreement.[10] Under the leadership of UNFCCC executive secretary Christiana Figueres, negotiation regained momentum after Copenhagen’s failure.[12] During the 2011 United Nations Climate Change Conference, the Durban Platform was established to negotiate a legal instrument governing climate change mitigation measures from 2020. The platform had a mandate to be informed by the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC and the work of the subsidiary bodies of the UNFCCC.[13] The resulting agreement was to be adopted in 2015.[14]

【参考译文】该协议确实为巴黎协定的自下而上的方法奠定了基础。[10] 在联合国气候变化框架公约执行秘书克里斯蒂娜·菲格雷斯的领导下,哥本哈根会议失败后,谈判重新获得了动力。[12] 在2011年联合国气候变化大会上,成立了德班平台,以协商一份从2020年开始管理气候变化减缓措施的法律文书。该平台的任务是参考政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)的第五次评估报告以及UNFCCC附属机构的工作。[13] 最终的协议将在2015年被采纳。[14]

2.2 谈判与采纳 | Negotiations and adoption

Main article: 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference

【主条目:2015年联合国气候变化大会】

Negotiations in Paris took place over a two-week span, and continued throughout the three final nights.[15][16] Various drafts and proposals had been debated and streamlined in the preceding year.[17] According to one commentator two ways in which the French increased the likelihood of success were: firstly to ensure that Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) were completed before the start of the negotiations, and secondly to invite leaders just for the beginning of the conference.[18]

【参考译文】巴黎的谈判历时两周,并在最后三个晚上持续进行。[15][16] 在之前的一年里,各种草案和提案已经过辩论并被简化。[17] 据一位评论员所说,法国增加成功可能性的两种方式是:首先确保在谈判开始前完成国家自定贡献预案(INDCs),其次邀请领导人仅参加大会开幕式。[18]

The negotiations almost failed because of a single word when the US legal team realized at the last minute that “shall” had been approved, rather than “should”, meaning that developed countries would have been legally obliged to cut emissions: the French solved the problem by changing it as a “typographical error”.[19] At the conclusion of COP21 (the 21st meeting of the Conference of the Parties), on 12 December 2015, the final wording of the Paris Agreement was adopted by consensus by the 195 UNFCCC participating member states and the European Union.[20] Nicaragua indicated they had wanted to object to the adoption as they denounced the weakness of the agreement, but were not given a chance.[21][22] In the agreement the members promised to reduce their carbon output “as soon as possible” and to do their best to keep global warming “to well below 2 degrees C” (3.6 °F).[23]

【参考译文】当美国法律团队在最后一刻意识到批准了“shall”而不是“should”,意味着发达国家将被法律义务要求削减排放时,谈判几乎失败,因为一个单词的问题:法国人通过将其更改为“印刷错误”解决了这个问题。[19] 在2015年12月12日第21次缔约方会议(COP21)结束时,巴黎协定的最终措辞由195个UNFCCC参与成员国和欧盟一致通过。[20] 尼加拉瓜表示他们本想反对采纳该协议,因为他们谴责该协议的软弱,但没有被给予机会。[21][22] 在协议中,成员国承诺“尽快”减少他们的碳排放,并尽最大努力将全球变暖“控制在远低于2摄氏度”(3.6°F)。[23]

2.3 签署和生效 | Signing and entry into force

The Paris Agreement was open for signature by states and regional economic integration organizations that are parties to the UNFCCC (the convention) from 22 April 2016 to 21 April 2017 at the UN Headquarters in New York.[24] Signing of the agreement is the first step towards ratification, but it is possible to accede to the agreement without signing.[25] It binds parties to not act in contravention of the goal of the treaty.[26] On 1 April 2016, the United States and China, which represent almost 40% of global emissions confirmed they would sign the Paris Climate Agreement.[27][28] The agreement was signed by 175 parties (174 states and the European Union) on the first day it was opened for signature.[29][30] As of March 2021, 194 states and the European Union have signed the agreement.[1]

【参考译文】巴黎协定于2016年4月22日至2017年4月21日在纽约联合国总部向UNFCCC(公约)的缔约国和区域经济一体化组织开放签署。[24] 签署协议是迈向批准的第一步,但即使未签署也可以加入该协议。[25] 它约束各方不得违反条约的目标。[26] 2016年4月1日,代表全球近40%温室气体排放量的美国和中国确认将签署巴黎气候协议。[27][28] 该协议在开放签署的第一天就得到了175个缔约方(174个国家和欧盟)的签署。[29][30] 截至2021年3月,已有194个国家和欧盟签署了该协议。[1]

The agreement would enter into force (and thus become fully effective) if 55 countries that produce at least 55% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (according to a list produced in 2015)[31] ratify or otherwise join the treaty.[32][25] Alternative ways to join the treaty are acceptance, approval or accession. The first two are typically used when a head of state is not necessary to bind a country to a treaty, whereas the latter typically happens when a country joins a treaty already in force.[33] After ratification by the European Union, the agreement obtained enough parties to enter into effect on 4 November 2016.[34]

【参考译文】如果55个国家(根据2015年的一份名单)批准或加入该条约,这项协议将生效(从而变得完全有效),这55个国家要占世界温室气体排放的至少55%。加入该条约的替代方法包括接受、批准或加入。前两种通常用于国家不需要元首来约束国家与条约相关时,而后一种通常发生在一个国家加入已生效的条约时。在欧盟批准之后,该协议获得了足够的缔约方,于2016年11月4日生效。

Both the EU and its member states are individually responsible for ratifying the Paris Agreement. A strong preference was reported that the EU and its 28 member states ratify at the same time to ensure that they do not engage themselves to fulfilling obligations that strictly belong to the other,[35] and there were fears by observers that disagreement over each member state’s share of the EU-wide reduction target, as well as Britain’s vote to leave the EU might delay the Paris pact.[36] However, the EU deposited its instruments of ratification on 5 October 2016, along with seven EU member states.[36]

【参考译文】欧盟及其各成员国均需单独负责批准巴黎协定。有强烈建议表示,欧盟及其28个成员国应同时批准,以确保它们不会承担严格属于另一方的义务。[35] 观察家们担心,各成员国对欧盟范围内减排目标份额的分歧,以及英国投票脱离欧盟可能会延迟巴黎协定的实施。[36] 然而,欧盟于2016年10月5日交存了其批准书,同时还有七个欧盟成员国也完成了这一程序。[36]

3. 缔约方 | Parties

Main article: List of parties to the Paris Agreement

【主条目:巴黎协定缔约方列表】

The EU and 194 states, totalling over 98% of anthropogenic emissions, have ratified or acceded to the agreement.[1][37][38] The only countries which have not ratified are some greenhouse gas emitters in the Middle East: Iran with 2% of the world total being the largest.[39] Libya and Yemen have also not ratified the agreement.[1] Eritrea is the latest country to ratify the agreement, on 7 February 2023.

【参考译文】欧盟和194个国家已批准或加入了该协议,这些国家的人为排放量总和超过全球的98%。[1][37][38] 尚未批准的唯一几个国家是中东的一些温室气体排放国:其中伊朗占全球总量的2%,是最大的排放国。[39] 利比亚和也门也未批准该协议。[1] 厄立特里亚是最新批准该协议的国家,于2023年2月7日完成批准。

Article 28 enables parties to withdraw from the agreement after sending a withdrawal notification to the depositary. Notice can be given no earlier than three years after the agreement goes into force for the country. Withdrawal is effective one year after the depositary is notified.[40]

【参考译文】第28条允许缔约方在向保存人发出撤回通知后退出协议。通知不得早于该协议对该国生效后的三年内提出。撤回在保存人收到通知后一年生效。[40]

3.1 美国退出并重新加入 | United States withdrawal and readmittance

Main article: United States withdrawal from the Paris Agreement

【主条目:美国退出巴黎协定】

On 4 August 2017, the Trump administration delivered an official notice to the United Nations that the United States, the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases after China,[41] intended to withdraw from the Paris Agreement as soon as it was eligible to do so.[42] The notice of withdrawal could not be submitted until the agreement was in force for three years for the US, on 4 November 2019.[43][44] The U.S. government deposited the notification with the Secretary General of the United Nations and officially withdrew one year later on 4 November 2020.[45][46] President Joe Biden signed an executive order on his first day in office, 20 January 2021, to re-admit the United States into the Paris Agreement.[47][48] Following the 30-day period set by Article 21.3, the U.S. was readmitted to the agreement.[49][50] United States Climate Envoy John Kerry took part in virtual events, saying that the US would “earn its way back” into legitimacy in the Paris process.[51] United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres welcomed the return of the United States as restoring the “missing link that weakened the whole”.[51]

【参考译文】2017年8月4日,特朗普政府向联合国正式递交通知,表示美国——仅次于中国的世界第二大温室气体排放国[41]——打算在符合条件时尽快退出巴黎协定。[42] 美国的退出通知必须等到该协议对美国生效三年后才能提交,即2019年11月4日。[43][44] 美国政府向联合国秘书长提交了通知,并在一年后的2020年11月4日正式退出。[45][46] 乔·拜登总统在就职第一天,即2021年1月20日签署了一项行政命令,重新让美国加入巴黎协定。[47][48] 按照第21.3条款规定的30天期限,美国被重新接纳进入该协议。[49][50] 美国气候特使约翰·克里参加了虚拟活动,表示美国将“赢得重返”巴黎进程的合法性。[51] 联合国秘书长安东尼奥·古特雷斯欢迎美国回归,称这恢复了“削弱整体的缺失环节”。[51]

4. 内容 | Content

The Paris Agreement is a short agreement with 16 introductory paragraphs and 29 articles. It contains procedural articles (covering, for example, the criteria for its entry into force) and operational articles (covering, for example, mitigation, adaptation and finance). It is a binding agreement, but many of its articles do not imply obligations or are there to facilitate international collaboration.[52] It covers most greenhouse gas emissions, but does not apply to international aviation and shipping, which fall under the responsibility of the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Maritime Organization, respectively.[53]

【参考译文】巴黎协定是一个简短的协议,包含16个引言段落和29条条款。它包括程序性条款(例如,涵盖其生效的标准)和操作性条款(例如,涵盖减缓、适应和财务)。这是一个具有约束力的协议,但其许多条款并不暗示义务或旨在促进国际合作。[52] 它涵盖了大部分温室气体排放,但不适用于国际航空和航运,这些分别属于国际民用航空组织和国际海事组织的责任范围。[53]

4.1 结构 | Structure

The Paris Agreement has been described as having a bottom-up structure, as its core pledge and review mechanism allows nations to set their own nationally determined contributions (NDCs), rather than having targets imposed top down.[54][55] Unlike its predecessor, the Kyoto Protocol, which sets commitment targets that have legal force, the Paris Agreement, with its emphasis on consensus building, allows for voluntary and nationally determined targets.[56] The specific climate goals are thus politically encouraged, rather than legally bound. Only the processes governing the reporting and review of these goals are mandated under international law. This structure is especially notable for the United States—because there are no legal mitigation or finance targets, the agreement is considered an “executive agreement rather than a treaty”. Because the UNFCCC treaty of 1992 received the consent of the US Senate, this new agreement does not require further legislation.[56]

【参考译文】巴黎协定被描述为具有自下而上的结构,因为它的核心承诺和审查机制允许各国设定自己的国家自定贡献(NDCs),而不是自上而下强加目标。[54][55] 与其前身京都议定书不同,后者设定了具有法律效力的承诺目标,巴黎协定强调建立共识,允许自愿和国家自定的目标。[56] 因此,具体的气候目标在政治上是被鼓励的,而不是法律上受到约束的。只有管理这些目标的报告和审查过程是根据国际法授权的。这种结构对美国来说尤其值得注意——因为没有法律上的减缓或财务目标,该协议被视为“行政协议而非条约”。由于1992年的联合国气候变化框架公约得到了美国参议院的同意,这项新协议不需要进一步立法。[56]

Another key difference between the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol is their scope. The Kyoto Protocol differentiated between Annex-I, richer countries with a historical responsibility for climate change, and non-Annex-I countries, but this division is blurred in the Paris Agreement as all parties are required to submit emissions reduction plans.[57] The Paris Agreement still emphasizes the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibility and Respective Capabilities—the acknowledgement that different nations have different capacities and duties to climate action—but it does not provide a specific division between developed and developing nations.[57]

【参考译文】巴黎协定与京都议定书之间的另一个关键区别在于它们的范围。京都议定书区分了附件一国家(对气候变化负有历史责任的较富裕国家)和非附件一国家,但在巴黎协定中这种划分变得模糊,因为所有缔约方都被要求提交减排计划。[57] 巴黎协定仍然强调“共同但有区别的责任和各自能力”原则——承认不同国家在气候行动上有不同的能力和责任——但它没有提供发达国家和发展中国家之间的具体划分。[57]

4.2 国家自定贡献 | Nationally determined contributions

Main article: Nationally determined contributions

【主条目:国家自定贡献】

Countries determine themselves what contributions they should make to achieve the aims of the treaty. As such, these plans are called nationally determined contributions (NDCs).[59] Article 3 requires NDCs to be “ambitious efforts” towards “achieving the purpose of this Agreement” and to “represent a progression over time”.[59] The contributions should be set every five years and are to be registered by the UNFCCC Secretariat.[60] Each further ambition should be more ambitious than the previous one, known as the principle of progression.[61] Countries can cooperate and pool their nationally determined contributions. The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions pledged during the 2015 Climate Change Conference are converted to NDCs when a country ratifies the Paris Agreement, unless they submit an update.[62][63]

【参考译文】各国自行决定为实现条约目标应作出的贡献。因此,这些计划被称为国家自定贡献(NDCs)。[59] 第三条规定,NDCs必须是“雄心勃勃的努力”,以“实现本协议的目的”,并且要“随着时间的推移而逐步提高”。[59] 贡献应每五年设定一次,并由联合国气候变化框架公约秘书处注册。[60] 每一个进一步的雄心都应该比前一个更加雄心勃勃,这被称为进步原则。[61] 各国可以合作并将他们的国家自定贡献合并。在2015年气候变化大会期间承诺的预期国家自定贡献在一个国家批准巴黎协定时转化为NDCs,除非他们提交了更新。[62][63]

The Paris Agreement does not prescribe the exact nature of the NDCs. At a minimum, they should contain mitigation provisions, but they may also contain pledges on adaptation, finance, technology transfer, capacity building and transparency.[64] Some of the pledges in the NDCs are unconditional, but others are conditional on outside factors such as getting finance and technical support, the ambition from other parties or the details of rules of the Paris Agreement that are yet to be set. Most NDCs have a conditional component.[65]

【参考译文】巴黎协定并未规定NDCs的确切性质。至少,它们应包含减缓措施的规定,但也可以包含关于适应、财务、技术转让、能力建设和透明度的承诺。[64] NDCs中的一些承诺是无条件的,但其他承诺则取决于外部因素,如获得财务和技术支持、其他方的雄心或尚未确定的巴黎协定规则的细节。大多数NDCs都有条件性组成部分。[65]

While the NDCs themselves are not binding, the procedures surrounding them are. These procedures include the obligation to prepare, communicate and maintain successive NDCs, set a new one every five years, and provide information about the implementation.[66] There is no mechanism to force[67] a country to set a NDC target by a specific date, nor to meet their targets.[68][69] There will be only a name and shame system[70] or as János Pásztor, the former U.N. assistant secretary-general on climate change, stated, a “name and encourage” plan.[71]

【参考译文】虽然NDCs本身不具有约束力,但围绕它们的程序却是有约束力的。这些程序包括准备、沟通和维护连续的NDCs的义务,每五年设定一个新的,并提供有关实施情况的信息。[66] 没有机制强制[67]一个国家在特定日期设定NDC目标,也没有机制强制它们实现目标。[68][69] 只会有一个点名批评系统[70],或者正如前联合国气候变化助理秘书长János Pásztor所说,是一个“点名鼓励”计划。[71]

4.3 全球库存核查 | Global stocktake

Under the Paris Agreement, countries must increase their ambition every five years. To facilitate this, the agreement established the Global Stocktake, which assesses progress, with the first evaluation in 2023. The outcome is to be used as input for new nationally determined contributions of parties.[72] The Talanoa Dialogue in 2018 was seen as an example for the global stocktake.[73] After a year of discussion, a report was published and there was a call for action, but countries did not increase ambition afterwards.[74]

【参考译文】根据巴黎协定,各国必须每五年提高其雄心水平。为了促进这一点,该协议建立了全球盘点机制,用于评估进展情况,首次评估将在2023年进行。其结果将作为各缔约方新的国家自定贡献的输入。[72] 2018年的塔拉诺阿对话被视为全球盘点的一个示例。[73] 经过一年的讨论,发布了一份报告并呼吁采取行动,但之后各国并没有提高其雄心水平。[74]

The stocktake works as part of the Paris Agreement’s effort to create a “ratcheting up” of ambition in emissions cuts. Because analysts agreed in 2014 that the NDCs would not limit rising temperatures below 2 °C, the global stocktake reconvenes parties to assess how their new NDCs must evolve so that they continually reflect a country’s “highest possible ambition”.[75] While ratcheting up the ambition of NDCs is a major aim of the global stocktake, it assesses efforts beyond mitigation. The five-year reviews will also evaluate adaptation, climate finance provisions, and technology development and transfer.[75]

【参考译文】全球盘点作为巴黎协定努力创造排放削减雄心“逐步提升”的一部分。因为分析人士在2014年就已同意,NDCs不足以将升温限制在2°C以下,全球盘点重新召集各方评估他们的新NDCs必须如何发展,以便它们持续反映一个国家的“最高可能雄心”。[75] 虽然提升NDCs的雄心是全球盘点的一个主要目标,但它也评估了减缓之外的其他努力。五年审查还将评估适应、气候融资规定以及技术开发和转让。[75]

4.4 减缓条款和碳市场 | Mitigation provisions and carbon markets

Article 6 has been flagged as containing some of the key provisions of the Paris Agreement.[76] Broadly, it outlines the cooperative approaches that parties can take in achieving their nationally determined carbon emissions reductions. In doing so, it helps establish the Paris Agreement as a framework for a global carbon market.[77] Article 6 is the only important part of the agreement yet to be resolved; negotiations in 2019 did not produce a result.[78] The topic was settled during the 2021 COP26 in Glasgow. A mechanism, the “corresponding adjustment”, was established to avoid double counting for emission offsets.[79]

【参考译文】第六条被标记为包含巴黎协定中一些关键条款。[76] 广义上,它概述了各方在实现其国家自定的碳排放减少目标时可以采取的合作方式。在此过程中,它有助于将巴黎协定确立为全球碳市场的框架。[77] 第六条是该协议唯一尚未解决的重要部分;2019年的谈判没有产生结果。[78] 这一议题在2021年格拉斯哥举行的COP26会议期间得到解决。建立了一个机制,“相应调整”,以避免排放抵消的双重计算。[79]

4.4.1 碳交易体系与国际气候协议目标交易机制的链接 | Linkage of carbon trading systems and ITMOs

Paragraphs 6.2 and 6.3 establish a framework to govern the international transfer of mitigation outcomes (ITMOs). The agreement recognizes the rights of parties to use emissions reductions outside of their own borders toward their NDC, in a system of carbon accounting and trading.[77] This provision requires the “linkage” of carbon emissions trading systems—because measured emissions reductions must avoid “double counting”, transferred mitigation outcomes must be recorded as a gain of emission units for one party and a reduction of emission units for the other,[76] a so called “corresponding adjustment”.[80] Because the NDCs, and domestic carbon trading schemes, are heterogeneous, the ITMOs will provide a format for global linkage under the auspices of the UNFCCC.[81] The provision thus also creates a pressure for countries to adopt emissions management systems—if a country wants to use more cost-effective cooperative approaches to achieve their NDCs, they will have to monitor carbon units for their economies.[82]

【参考译文】第六。二条和第六。三条建立了一个框架,用以规范减缓成果的国际转移(ITMOs)。该协议承认各方有权使用其境外的排放减少额度来实现自己的国家自定贡献(NDC),在碳核算和交易体系中。[77] 这项规定要求“链接”碳排放交易系统——因为衡量出的排放减少必须避免“双重计算”,转移的减缓成果必须记录为一方的排放单位增加和另一方的排放单位减少,[76] 所谓的“相应调整”。[80] 由于NDCs和国内碳交易计划是异质性的,ITMOs将在联合国气候变化框架公约(UNFCCC)的支持下提供全球链接的格式。[81] 因此,该规定也为各国采用排放管理系统创造了压力——如果一个国家想要使用更具成本效益的合作方式来实现其NDCs,他们将不得不为其经济体监测碳单位。[82]

So far, as the only country who wants to buy ITMOs, Switzerland has signed deals regarding ITMO tradings with Peru, Ghana, Senegal, Georgia, Dominica, Vanuatu, Thailand and Ukraine.

4.4.2 可持续发展机制 | Sustainable Development Mechanism

Paragraphs 6.4-6.7 establish a mechanism “to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gases and support sustainable development”.[88] Though there is no official name for the mechanism as yet, it has been referred to as the Sustainable Development Mechanism or SDM.[89][78] The SDM is considered to be the successor to the Clean Development Mechanism, a mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol by which parties could collaboratively pursue emissions reductions.[90]

【参考译文】第六。四条至第六。七条确立了一种机制,“有助于减缓温室气体排放并支持可持续发展”。[88] 尽管该机制目前尚无官方名称,但它已被称为可持续发展机制或SDM。[89][78] SDM被视为清洁发展机制(CDM)的继任者,CDM是京都议定书下的一种机制,通过该机制各方可以合作追求减排。[90]

The SDM is set to largely resemble the Clean Development Mechanism, with the dual goal of contributing to global GHG emissions reductions and supporting sustainable development.[91] Though the structure and processes governing the SDM are not yet determined, certain similarities and differences from the Clean Development Mechanisms have become clear. A key difference is that the SDM will be available to all parties as opposed to only Annex-I parties, making it much wider in scope.[92]

【参考译文】SDM的设定在很大程度上将类似于清洁发展机制(CDM),其双重目标是促进全球温室气体排放减少和支持可持续发展。[91] 尽管管理SDM的结构和流程尚未确定,但与清洁发展机制的某些相似之处和差异已经变得清晰。一个关键的区别是,SDM将向所有缔约方开放,而不仅仅是附件一缔约方,使其范围更广。[92]

The Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol was criticized for failing to produce either meaningful emissions reductions or sustainable development benefits in most instances.[93] and for its complexity. It is possible that the SDM will see difficulties.[81]

【参考译文】京都议定书下的清洁发展机制被批评在大多数情况下未能产生有意义的排放减少或可持续发展效益。[93] 并且因其复杂性而受到批评。SDM可能会遇到困难。[81]

4.5 气候变化适应规定 | Climate change adaptation provisions

Climate change adaptation received more focus in Paris negotiations than in previous climate treaties. Collective, long-term adaptation goals are included in the agreement, and countries must report on their adaptation actions, making it a parallel component with mitigation.[94] The adaptation goals focus on enhancing adaptive capacity, increasing resilience, and limiting vulnerability.[95]

【参考译文】在之前的气候条约中,气候变化适应在巴黎谈判中受到了更多的关注。集体的长期适应目标被纳入了该协议,各国必须报告其适应行动,使其成为与减缓并行的组成部分。[94] 适应目标侧重于增强适应能力、提高韧性和限制脆弱性。[95]

5. 特定关注议题 | Specific topics of concern

5.1 确保融资 | Ensuring finance

Further information: Climate finance and Green Climate Fund

【进一步信息:气候融资和绿色气候基金】

Developed countries reaffirmed the commitment to mobilize $100 billion a year in climate finance by 2020, and agreed to continue mobilising finance at this level until 2025.[96] The money is for supporting mitigation and adaptation in developing countries.[97] It includes finance for the Green Climate Fund, which is a part of the UNFCCC, but also for a variety of other public and private pledges. The Paris Agreement states that a new commitment of at least $100 billion per year has to be agreed before 2025.[98]

【参考译文】发达国家重申了到2020年每年筹集1000亿美元气候融资的承诺,并同意继续以这一水平动员资金直至2025年。[96] 这些资金将用于支持发展中国家的减缓和适应措施。[97] 它包括为绿色气候基金提供的融资,该基金是联合国气候变化框架公约的一部分,但也包括各种其他公共和私人承诺的资金。巴黎协定规定,在2025年之前必须至少每年达成1000亿美元的新承诺。[98]

Though both mitigation and adaptation require increased climate financing, adaptation has typically received lower levels of support and has mobilized less action from the private sector.[94] A report by the OECD found that 16% of global climate finance was directed toward climate adaptation in 2013–2014, compared to 77% for mitigation.[99] The Paris Agreement called for a balance of climate finance between adaptation and mitigation, and specifically increasing adaptation support for parties most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including Least developed countries and Small Island Developing States. The agreement also reminds parties of the importance of public grants, because adaptation measures receive less investment from the public sector.[94]

【参考译文】尽管减缓和适应都需要增加气候融资,但适应通常获得的支持水平较低,并且从私营部门动员的行动也较少。[94] 经合组织的一份报告发现,在2013-2014年间,全球气候融资中只有16%用于气候适应,相比之下,77%用于减缓。[99] 巴黎协定呼吁在适应和减缓之间平衡气候融资,并特别强调增加对最容易受到气候变化影响的缔约方的适应支持,包括最不发达国家和小岛屿发展中国家。该协议还提醒各缔约方公共拨款的重要性,因为适应措施从公共部门的投资较少。[94]

In 2015, twenty Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and members of the International Development Finance Club introduced five principles to maintain widespread climate action in their investments: commitment to climate strategies, managing climate risks, promoting climate smart objectives, improving climate performance and accounting for their own actions. As of January 2020, the number of members abiding by these principles grew to 44.[100]

【参考译文】2015年,二十家多边开发银行(MDBs)和国际发展金融俱乐部的成员引入了五项原则,以在其投资中保持广泛的气候行动:承诺气候战略、管理气候风险、促进气候智能目标、提高气候绩效以及对其自身行动进行核算。截至2020年1月,遵守这些原则的成员数量增加到44个。[100]

Some specific outcomes of the elevated attention to adaptation financing in Paris include the G7 countries‘ announcement to provide US$420 million for climate risk insurance, and the launching of a Climate Risk and Early Warning Systems (CREWS) Initiative.[101] The largest donors to multilateral climate funds, which includes the Green Climate Fund, are the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Germany, France and Sweden.[102]

【参考译文】在巴黎对适应融资关注度提升的一些具体成果包括,G7国家宣布提供4.2亿美元用于气候风险保险,以及启动气候风险和早期预警系统(CREWS)倡议。[101] 向多边气候基金捐款最多的国家包括美国、英国、日本、德国、法国和瑞典,这些多边气候基金中就包括绿色气候基金。[102]

5.2 损失和损害 | Loss and damage

Main article: Loss and damage (climate change)

【主条目:损失和损害(气候变化)】

It is not possible to adapt to all effects of climate change: even in the case of optimal adaptation, severe damage may still occur. The Paris Agreement recognizes loss and damage of this kind.[103] Loss and damage can stem from extreme weather events, or from slow-onset events such as the loss of land to sea level rise for low-lying islands.[56] Previous climate agreements classified loss and damage as a subset of adaptation.[103]

【参考译文】适应气候变化的所有影响是不可能的:即使在最佳适应的情况下,也可能发生严重的损害。巴黎协定认识到了这类损失和损害。[103] 损失和损害可能源于极端天气事件,或者源于缓慢发生的事件,如低洼岛屿因海平面上升而失去土地。[56] 以往的气候协议将损失和损害归类为适应的一个子集。[103]

The push to address loss and damage as a distinct issue in the Paris Agreement came from the Alliance of Small Island States and the Least Developed Countries, whose economies and livelihoods are most vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change.[56] The Warsaw Mechanism, established two years earlier during COP19 and set to expire in 2016, categorizes loss and damage as a subset of adaptation, which was unpopular with many countries. It is recognized as a separate pillar of the Paris Agreement.[104] The United States argued against this, possibly worried that classifying the issue as separate from adaptation would create yet another climate finance provision.[56] In the end, the agreement calls for “averting, minimizing, and addressing loss and damage”[7] but specifies that it cannot be used as the basis for liability. The agreement adopts the Warsaw Mechanism, an institution that will attempt to address questions about how to classify, address, and share responsibility for loss.[103]

【参考译文】将损失和损害作为一个独立问题在《巴黎协定》中提出的推动力量来自小岛屿国家联盟和最不发达国家,这些国家的经济和生计最容易受到气候变化负面影响的打击。[56] 两年前在COP19期间建立并于2016年到期的华沙机制将损失和损害归类为适应的一个子集,这在许多国家中并不受欢迎。它被认定为《巴黎协定》的一个独立支柱。[104] 美国对此表示反对,可能担心将这个问题与适应分开分类会创造另一个气候融资条款。[56] 最终,该协议呼吁“避免、最小化并解决损失和损害”,[7] 但明确指出它不能作为责任的基础。该协议采纳了华沙机制,这是一个将尝试解决如何分类、解决和分享损失责任问题的机构。[103]

5.3 透明度 | Transparency

Main article: Enhanced Transparency Framework

【主条目:增强透明度框架】

The parties are legally bound to have their progress tracked by technical expert review to assess achievement toward the NDC and to determine ways to strengthen ambition.[105] Article 13 of the Paris Agreement articulates an “enhanced transparency framework for action and support” that establishes harmonized monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) requirements. Both developed and developing nations must report every two years on their mitigation efforts, and all parties will be subject to technical and peer review.[105]

【参考译文】各方在法律上有义务通过技术专家审查来跟踪其进展,以评估实现国家自定贡献目标的情况,并确定加强雄心的方法。[105] 《巴黎协定》第13条阐述了一个“行动和支持的增强透明度框架”,该框架建立了协调一致的监测、报告和核查(MRV)要求。发达国家和发展中国家都必须每两年报告一次他们的减缓努力,所有缔约方都将接受技术和同行评审。[105]

While the enhanced transparency framework is universal, the framework is meant to provide “built-in flexibility” to distinguish between developed and developing countries’ capacities. The Paris Agreement has provisions for an enhanced framework for capacity building, recognizes the varying circumstances of countries, and notes that the technical expert review for each country consider that country’s specific capacity for reporting.[106] Parties to the agreement send their first Biennial Transparency Report (BTR), and greenhouse gas inventory figures to the UNFCCC by 2024 and every two years after that. Developed countries submit their first BTR in 2022 and inventories annually from that year.[107] The agreement also develops a Capacity-Building Initiative for Transparency to assist developing countries in building the necessary institutions and processes for compliance.[106]

【参考译文】虽然增强透明度框架是全球性的,但该框架旨在提供“内置的灵活性”,以区分发达国家和发展中国家的能力。巴黎协定为增强能力建设的框架提供了条款,认识到各国的不同情况,并指出对每个国家的技术专家审查应考虑该国报告的具体能力。[106] 协议各方将在2024年及之后每两年向联合国气候变化框架公约(UNFCCC)提交他们的首份双年透明度报告(BTR)和温室气体清单数据。发达国家将从2022年开始提交他们的首份BTR,并从那一年起每年提交清单。[107] 协议还开发了一个透明度能力建设倡议,以协助发展中国家建立遵守协议所需的机构和流程。[106]

Flexibility can be incorporated into the enhanced transparency framework via the scope, level of detail, or frequency of reporting, tiered based on a country’s capacity. The requirement for in-country technical reviews could be lifted for some less developed or small island developing countries. Ways to assess capacity include financial and human resources in a country necessary for NDC review.[106]

【参考译文】灵活性可以通过报告的范围、详细程度或频率纳入增强透明度框架,并根据国家的能力进行分层。对于一些较不发达或小岛屿发展中国家,国内技术审查的要求可能被取消。评估能力的方式包括一个国家进行NDC审查所需的财政和人力资源。[106]

5.4 诉讼 | Litigation

Main article: Climate change litigation

【主条目:气候变化诉讼】

The Paris Agreement has become a focal point of climate change litigation. One of the first major cases in this area was State of the Netherlands v. Urgenda Foundation, which was raised against the Netherlands’ government after it had reduced its planned emissions reductions goal for 2030 prior to the Paris Agreement. After an initial ruling against the government in 2015 that required it to maintain its planned reduction, the decision was upheld on appeals through the Supreme Court of the Netherlands in 2019, ruling that the Dutch government failed to uphold human rights under Dutch law and the European Convention on Human Rights by lowering its emission targets.[5] The 2 °C temperature target of the Paris Agreement provided part of the judgement’s legal basis.[108] The agreement, whose goals are enshrined in German law, also formed part of the argumentation in Neubauer et al. v. Germany, where the court ordered Germany to reconsider its climate targets.[109]

【参考译文】《巴黎协定》已成为气候变化诉讼的焦点。这一领域的第一个重大案件之一是荷兰国诉乌尔根达基金会案,该案是在荷兰政府在巴黎协定之前降低其2030年计划减排目标后提起的。2015年最初裁决要求政府维持其计划中的减排目标,该决定在2019年通过荷兰最高法院的上诉得到维持,裁定荷兰政府未能通过降低排放目标来维护荷兰法律和欧洲人权公约下的人权。[5] 巴黎协定的2°C温度目标是判决的法律依据之一。[108] 在德国,该协议的目标已被确立为德国法律的一部分,也构成了诺伊鲍尔等人诉德国案中论证的一部分,在该案中,法院命令德国重新考虑其气候目标。[109]

In May 2021, the district court of The Hague ruled against oil company Royal Dutch Shell in Milieudefensie et al v Royal Dutch Shell. The court ruled that it must cut its global emissions by 45% from 2019 levels by 2030, as it was in violation of human rights. This lawsuit was considered the first major application of the Paris Agreement towards a corporation.[6]

【参考译文】2021年5月,海牙地区法院在“Milieudefensie et al诉荷兰皇家壳牌公司”一案中裁定石油公司荷兰皇家壳牌败诉。法院裁定该公司必须将其全球排放量从2019年水平削减45%,并在2030年前实现这一目标,因为它违反了人权。这起诉讼被视为首次将《巴黎协定》应用于一家企业的重大案例。[6]

5.5 人权 | Human rights

Further information: Human rights

【更多信息请看:人权】

On 4 July 2022, the Supreme Federal Court of Brazil recognized the Paris agreement as a “human rights treaty“. According to the ruling of the court in Brazil it should “supersede national law”.[110][111] In the same month the United Nations Human Rights Council in a resolution “(A/HRC/50/L.10/Rev.1) on Human rights and climate change, adopted without a vote” called to ratify and implement the agreement and emphasized the link between stopping climate change and the right to food.[112]

【参考译文】2022年7月4日,巴西最高联邦法院认定《巴黎协定》为“人权条约”。根据巴西法院的裁决,它应“凌驾于国家法律之上”。[110][111] 同月,联合国人权理事会在一项“未经投票通过的决议(A/HRC/50/L.10/Rev.1)关于人权与气候变化”中呼吁批准并实施该协议,并强调了阻止气候变化与食物权利之间的联系。[112]

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights officially recognized that “Climate change threatens the effective enjoyment of a range of human rights including those to life, water and sanitation, food, health, housing, self-determination, culture and development.”[113]

【参考译文】联合国人权高专办正式承认,“气候变化威胁到包括生命、水和卫生、食物、健康、住房、自决、文化和发展等一系列人权的有效享有。”[113]

6. 实施 | Implementation

The Paris Agreement is implemented via national policy. It would involve improvements to energy efficiency to decrease the energy intensity of the global economy. Implementation also requires fossil fuel burning to be cut back and the share of sustainable energy to grow rapidly. Emissions are being reduced rapidly in the electricity sector, but not in the building, transport and heating sector. Some industries are difficult to decarbonize, and for those carbon dioxide removal may be necessary to achieve net zero emissions.[114] In a report released in 2022 the IPCC promotes the need for innovation and technological changes in combination with consumption and production behavioral changes to meet Paris Agreement objectives.[115]

【参考译文】《巴黎协定》通过国家政策来实施。这将涉及提高能源效率,以降低全球经济的能源强度。实施还要求削减化石燃料的燃烧,并迅速增加可持续能源的份额。电力部门的排放正在迅速减少,但建筑、交通和供暖部门的排放并未减少。一些行业难以脱碳,对于这些行业来说,可能需要通过二氧化碳移除来实现净零排放。[114] 在2022年发布的一份报告中,政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)强调了为了满足《巴黎协定》的目标,需要创新和技术变革,结合消费和生产行为变化。[115]

To stay below 1.5 °C of global warming, emissions need to be cut by roughly 50% by 2030. This is an aggregate of each country’s nationally determined contributions. By mid-century, CO2 emissions would need to be cut to zero, and total greenhouse gases would need to be net zero just after mid-century.[4]

【参考译文】为了将全球变暖控制在1.5°C以下,排放量需要在2030年前大约减少50%。这是每个国家自定贡献的总和。到本世纪中叶,二氧化碳排放量需要降至零,而总温室气体排放量需要在本世纪中叶后不久实现净零。[4]

There are barriers to implementing the agreement. Some countries struggle to attract the finance necessary for investments in decarbonization. Climate finance is fragmented, further complicating investments. Another issue is the lack of capabilities in government and other institutions to implement policy. Clean technology and knowledge is often not transferred to countries or places that need it.[114] In December 2020, the former chair of the COP 21, Laurent Fabius, argued that the implementation of the Paris Agreement could be bolstered by the adoption of a Global Pact for the Environment.[116] The latter would define the environmental rights and duties of states, individuals and businesses.[117]

【参考译文】实施该协议存在障碍。一些国家难以吸引进行脱碳投资所需的资金。气候融资分散,进一步复杂化了投资问题。另一个问题是政府和其他机构缺乏实施政策的能力。清洁技术和知识往往没有转移到需要它的国家或地区。[114] 2020年12月,COP 21的前主席洛朗·法比尤斯(Laurent Fabius)认为,通过采纳全球环境公约可以加强《巴黎协定》的实施。[116] 后者将定义国家、个人和企业的环境权利和义务。[117]

6.1 履行要求 | Fulfillment of requirements

7. 收效与争论 | Reception and debates

The agreement was lauded by French President François Hollande, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC.[122] The president of Brazil, Dilma Rousseff, called the agreement “balanced and long-lasting”,[123] and India’s prime minister Narendra Modi commended the agreement’s climate justice.[124][125] When the agreement achieved the required signatures in October 2016, US President Barack Obama said that “Even if we meet every target, we will only get to part of where we need to go.”[126] He also stated “this agreement will help delay or avoid some of the worst consequences of climate change [and] will help other nations ratchet down their emissions over time.”[126]

【参考译文】法国总统弗朗索瓦·奥朗德、联合国秘书长潘基文和《联合国气候变化框架公约》执行秘书克里斯蒂娜·菲格雷斯都对该协议表示赞扬。[122] 巴西总统迪尔玛·罗塞夫称该协议为“平衡且持久的”,[123] 印度总理纳伦德拉·莫迪则称赞该协议的气候正义。[124][125] 当该协议在2016年10月获得所需签名时,美国总统巴拉克·奥巴马表示,“即使我们达到了每一个目标,我们也只会达到我们需要走的一部分路程。”[126] 他还说:“这项协议将有助于推迟或避免一些气候变化的最坏后果,[并且] 将帮助其他国家逐步减少他们的排放。”[126]

Some environmentalists and analysts reacted cautiously, acknowledging the “spirit of Paris” in bringing together countries, but expressing less optimism about the pace of climate mitigation and how much the agreement could do for poorer countries.[127] James Hansen, a former NASA scientist and leading climate change expert, voiced anger that most of the agreement consists of “promises” or aims and not firm commitments and called the Paris talks a fraud with “no action, just promises”.[128] Criticism of the agreement from those arguing against climate action has been diffuse, which may be due to the weakness of the agreement. This type of criticism typically focusses on national sovereignty and ineffectiveness of international action.

【参考译文】一些环保人士和分析家对此反应谨慎,他们承认巴黎协定在团结各国方面的“精神”,但对气候减缓的步伐以及该协议能为较贫穷国家带来多少帮助表示不太乐观。[127] 前NASA科学家、著名气候变化专家詹姆斯·汉森对大部分协议内容仅为“承诺”或目标而非坚定承诺表示愤怒,并称巴黎会谈是一场骗局,只有“空洞的承诺而无实际行动”。[128] 那些反对气候行动的人士对协议的批评则较为分散,这可能是因为协议本身的弱点。这类批评通常集中在国家主权和国际行动的无效性上。

《巴黎协定》生效后,地球暖化持续加速,2018年全球温室气体排放量(包括因土地利用变更而产生)达到553亿吨二氧化碳当量,当中化石燃料使用和工业活动造成的排放达到375亿吨二氧化碳当量,较2017年增长2%。[17]2019年全球温室气体排放量(包括因土地利用变更而产生)达到591亿吨二氧化碳当量。[18]

根据联合国气候变化2022年10月发布的新报告显示,虽然各国正在努力减少温室气体排放,但这些努力仍不足以将全球温度在本世纪末限制在1.5摄氏度以内。根据现有承诺,到2030年温室气体排放量将比2010年增长10.6%。与去年预测的2030年温室气体排放量较2010年增长13.7%相比,这一数据有所改善。[19]。

7.1 有效性 | Effectiveness

The effectiveness of the Paris Agreement to reach its climate goals is under debate, with most experts saying it is insufficient for its more ambitious goal of keeping global temperature rise under 1.5 °C.[129][130] Many of the exact provisions of the Paris Agreement have yet to be straightened out, so that it may be too early to judge effectiveness.[129] According to the 2020 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), with the current climate commitments of the Paris Agreement, global mean temperatures will likely rise by more than 3 °C by the end of the 21st century. Newer net zero commitments were not included in the Nationally Determined Contributions, and may bring down temperatures a further 0.5 °C.[131]

【参考译文】巴黎协定实现其气候目标的有效性存在争议,大多数专家认为它不足以实现其更雄心勃勃的目标,即将全球温度上升控制在1.5°C以下。[129][130] 巴黎协定的许多具体条款尚未明确,因此现在判断其有效性可能为时尚早。[129] 根据2020年联合国环境规划署(UNEP)的数据,按照巴黎协定目前的气候承诺,全球平均温度到21世纪末可能会上升超过3°C。新的净零排放承诺未包括在国家自定贡献中,可能会进一步将温度降低0.5°C。[131]

With initial pledges by countries inadequate, faster and more expensive future mitigation would be needed to still reach the targets.[132] Furthermore, there is a gap between pledges by countries in their NDCs and implementation of these pledges; one third of the emission gap between the lowest-costs and actual reductions in emissions would be closed by implementing existing pledges.[133] A pair of studies in Nature found that as of 2017 none of the major industrialized nations were implementing the policies they had pledged, and none met their pledged emission reduction targets,[134] and even if they had, the sum of all member pledges (as of 2016) would not keep global temperature rise “well below 2 °C”.[135][136]

【参考译文】由于各国最初的承诺不足,为了仍然达到目标,需要更快速和更昂贵的未来减缓措施。此外,各国在其国家自主贡献文件(NDCs)中的承诺和这些承诺的实施之间存在差距;实施现有承诺将会缩小最低成本和实际减排之间的排放差距的三分之一。《自然》杂志上的一对研究发现,截至2017年,主要工业化国家都没有实施他们曾经承诺的政策,也没有达到他们承诺的减排目标,即使他们已经达到了,根据2016年的情况,所有成员国的承诺总和也不能使全球温度上升保持在“远低于2°C”的范围内。

In 2021, a study using a probabilistic model concluded that the rates of emissions reductions would have to increase by 80% beyond NDCs to likely meet the 2 °C upper target of the Paris Agreement, that the probabilities of major emitters meeting their NDCs without such an increase is very low. It estimated that with current trends the probability of staying below 2 °C of warming is 5% – and 26% if NDCs were met and continued post-2030 by all signatories.[137]

【参考译文】2021年,一项使用概率模型的研究得出结论,为了有可能达到巴黎协定的2°C上限目标,减排率必须比国家自定贡献(NDCs)增加80%,而且主要排放国在不增加减排率的情况下实现其NDCs的可能性非常低。该研究估计,按照目前的趋势,全球气温上升保持在2°C以下的概率为5%——如果所有签署国在2030年后继续并实现NDCs,这一概率将上升到26%。[137]

As of 2020, there is little scientific literature on the topics of the effectiveness of the Paris Agreement on capacity building and adaptation, even though they feature prominently in the Paris Agreement. The literature available is mostly mixed in its conclusions about loss and damage, and adaptation.[129]

【参考译文】截至2020年,关于巴黎协定在能力建设和适应方面的有效性的科学文献很少,尽管这些主题在巴黎协定中占据了显著位置。现有的文献在其对损失和损害以及适应的结论上大多是复杂且不一致的。[129]

According to the stocktake report, the agreement has a significant effect: while in 2010 the expected temperature rise by 2100 was 3.7–4.8 °C, at COP 27 it was 2.4–2.6°C and if all countries will fulfill their long-term pledges even 1.7–2.1 °C. Despite it, the world is still very far from reaching the aim of the agreement: limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees. For doing this, emissions must peak by 2025.[120][121]

【参考译文】根据盘点报告,该协议产生了显著效果:2010年预期到2100年的温度上升为3.7–4.8°C,在COP 27时下降到了2.4–2.6°C,如果所有国家都履行他们的长期承诺,甚至可能降至1.7–2.1°C。尽管如此,世界距离实现协议的目标——将温度上升限制在1.5度以内——仍然非常遥远。为此,排放量必须在2025年达到峰值。[120][121]

分享到: