中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。

辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及根据名称精确检索已搬运的词条,请点击这里访问辽观网站。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

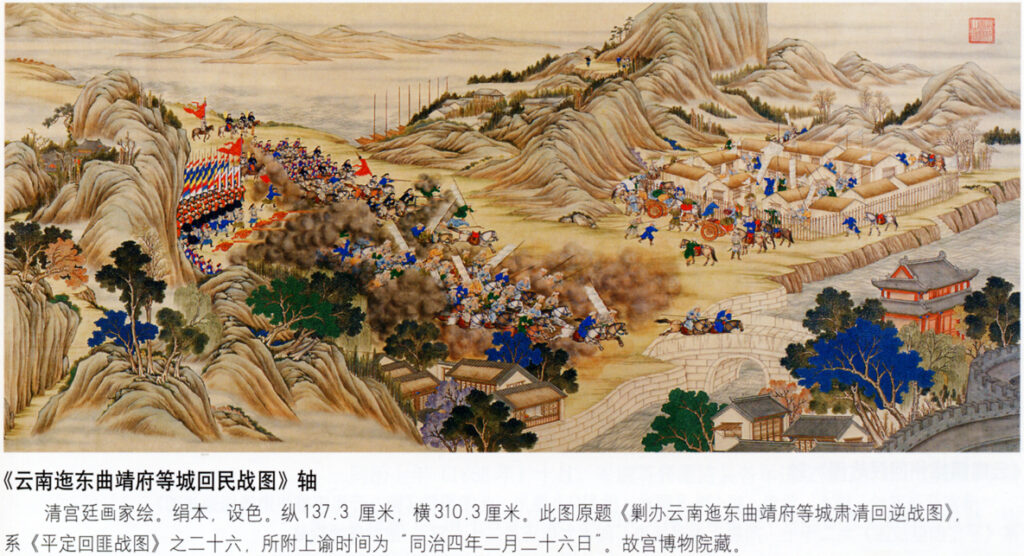

图片题注:Map of the Muslim Uprisings against the Qing Empire.

参考译文:穆斯林反抗清帝国的起义地图。

图片来源:The British Library

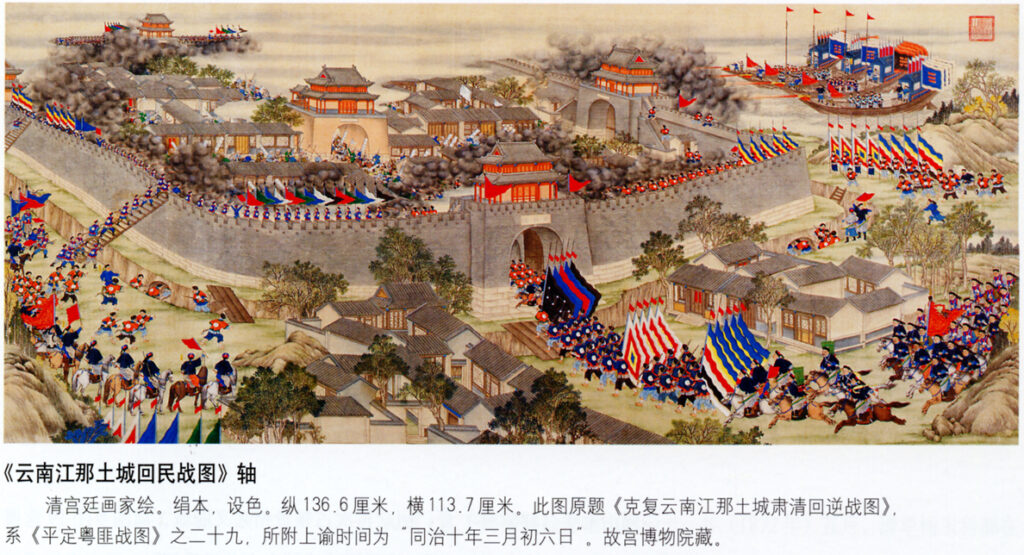

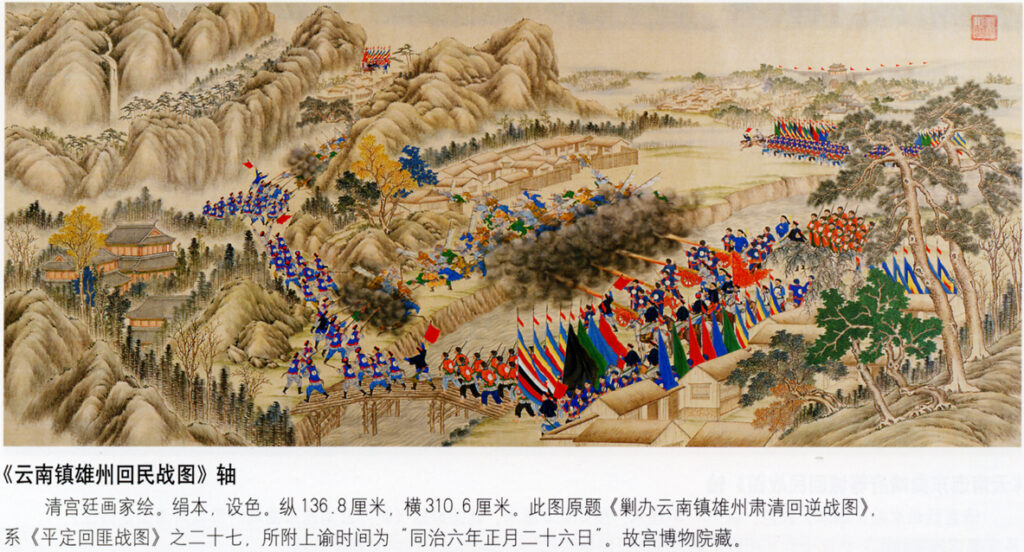

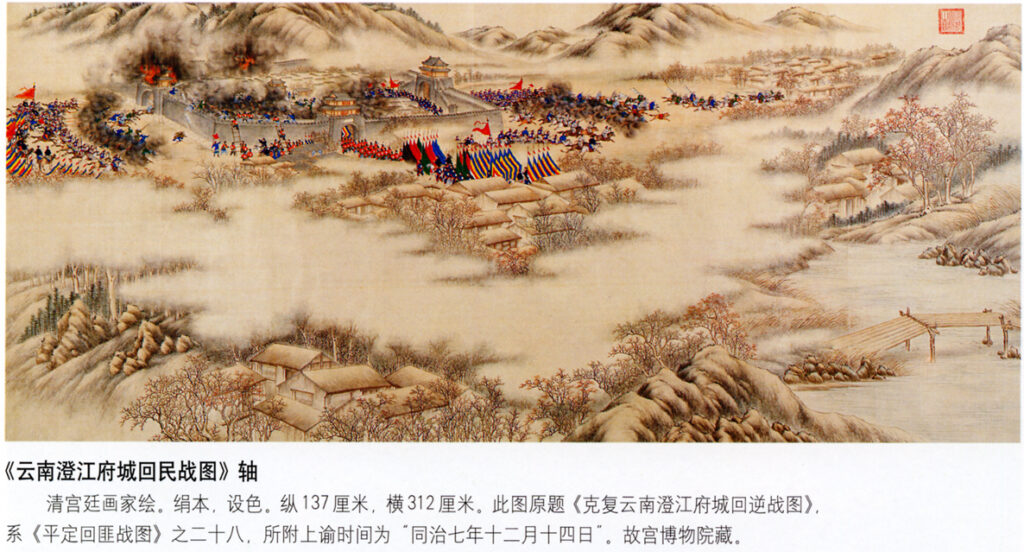

云南回变,是1856年发生在清朝云南省的一次大规模回族穆斯林武装的暴动,1872年被清军镇压。

The Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873), also known as the Du Wenxiu Rebellion (Tu Wen-hsiu Rebellion), was a rebellion of the Muslim Hui people and other (Muslim as well as non-Muslim) ethnic groups against the Manchu-led Qing dynasty in southwestern Yunnan Province, as part of a wave of Hui-led multi-ethnic unrest.

【参考译文】班泰起义(1856-1873 年)又称杜文秀起义,是回族穆斯林和其他民族(穆斯林和非穆斯林)反抗满族领导的清朝统治的起义,起义发生在云南省西南部,是回族领导的多民族动乱浪潮的一部分。

The name “Panthay” is a Burmese word, which is said to be identical with the Shan word Pang hse.[1] It was the name by which the Burmese called the Chinese Muslims who came with caravans to Burma from the Chinese province of Yunnan. The name was not used or known in Yunnan itself.[2] The rebellion referred to itself as the Pingnan Kingdom, meaning Pacified Southern Kingdom.[3]

【参考译文】“班泰”这个名字是一个缅甸语词,据说与掸族词 Pang hse 相同。[1] 这是缅甸人对从中国云南省随商队来到缅甸的中国穆斯林的称呼。这个名字在云南本身并没有使用或为人所知。[2] 这场叛乱自称为平南国,意为平定的南方王国。[3]

| Panthay Rebellion【云南回乱】 | |

|---|---|

| Date【时间】 1856–1873 Location【地点】 Yunnan, Qing Empire【清帝国云南省】 Result【结果】 Qing victory; Fall of Pingnan Guo; Weakening of the Qing dynasty【清朝胜利;平南国沦陷;清朝衰落】 | |

| Belligerents【交战方】 | |

| Commanders and leaders【指挥官和领导人】 | |

| Cen Yuying【岑毓英】 Ma Rulong【马如龙】 | Du Wenxiu【杜文秀】 Ma Shenglin †【马胜林(已故)】 Ma Shilin【马士林】 |

| Strength【力量】 | |

| Manchu, Han Chinese, and Loyalist Muslim troops 【满族、汉族和效忠派穆斯林军队】 | Rebel Muslims, Rebel Han Chinese and Muslim ethnic minorities 【叛乱的穆斯林、叛乱的汉族和穆斯林少数民族】 |

| Casualties and losses【人员伤亡和损失】 | |

| 1,000,000 dead【100万死亡】 | 1,000,000 (including Muslim and non-Muslim civilians and soldiers) 【100万(包括穆斯林和非穆斯林平民和士兵)】 |

目录

1. 背景 | Background

据传19世纪,为争夺土地和矿权,云南的汉族地主商人和回族地主商人之间发生的冲突,这些冲突日益激化。

道光二十六年(1846年),保山县发生永昌汉、回互斗事件。杜文秀等人先后前往昆明和北京上诉,都未得满意答复。[1]

In 1856, a massacre of Muslims organized by a Qing Manchu official responsible for suppressing the revolt in the provincial capital of Kunming sparked a province-wide multi-ethnic insurgency.[4][5][6] The Manchu official who started the anti-Muslim massacre was Shuxing’a, who developed a deep hatred of Muslims after an incident where he was stripped naked and nearly lynched by a mob of Muslims. He ordered several Muslim rebels to be slowly sliced to death.[7][8] However, Tariq Ali claimed in his works that the Muslims who had nearly lynched Shuxing’a were not Hui, but belonged to another ethnicity; nevertheless, the Manchu official blamed all Muslims for the incident.[9][10]

【参考译文】1856 年,负责镇压省会昆明叛乱的清朝满族官员组织了一场针对穆斯林的大屠杀,此举引发了全省多民族的叛乱。[4][5][6] 发起反穆斯林大屠杀的满族官员是舒兴阿,他在一次事件中被一群穆斯林暴徒剥光衣服并差点被私刑处死,从此对穆斯林产生了深深的仇恨。他下令将几名穆斯林叛乱分子慢慢地砍死。[7][8] 然而,塔里克·阿里在他的著作中声称,差点私刑处死舒兴阿的穆斯林不是回族,而是属于另一个民族;尽管如此,这位满族官员还是将事件归咎于所有穆斯林。[9][10]

Meanwhile, in Dali City in western Yunnan, an independent kingdom was established by Du Wenxiu (1823–1872), who was born in Yongchang to a Han Chinese family which had converted to Islam.[5][11] Du Wenxiu was of Han Chinese origin despite being a Muslim and he led both Hui Muslims and Han Chinese in his civil and military bureaucracy. Du Wenxiu was fought against by another Muslim leader, the defector to the Qing Ma Rulong. The Muslim scholar Ma Dexin, who said that Neo-Confucianism was reconcilable with Islam, approved of Ma Rulong defecting to the Qing and also assisted other Muslims in defecting.[12][13]

【参考译文】与此同时,在云南西部的大理市,杜文秀(1823-1872 年)建立了一个独立王国。杜文秀出生于永昌一个皈依伊斯兰教的汉族家庭。[5][11] 杜文秀虽然是穆斯林,但其实是汉族人,他在文武官僚机构中领导回族穆斯林和汉族人。杜文秀遭到另一位穆斯林领袖、投奔清朝的马如龙的反对。穆斯林学者马德信认为理学与伊斯兰教是可以调和的,他赞成马如龙投奔清朝,并帮助其他穆斯林投奔清朝。[12][13]

Du Wenxiu openly claimed that his aims were to drive out the Manchus, unite with the ethnic Han, and destroy those who supported the Qing.[14] Du Wenxiu did not blame Han for the massacres of Hui, instead, he blamed the Manchu regime for the massacres, saying that the Manchus were foreign to China and that they alienated the Chinese and other minorities.[15][16] Anti-Manchu rhetoric was frequently used by Du, as he further tried to convince both the Han and the Hui to join forces to overthrow the Manchu Qing after 200 years of their rule.[17][18] Du invited the fellow Hui Muslim leader Ma Rulong to join him in driving the Manchu Qing out and “recover China”.[19] For his war against Manchu “oppression”, Du “became a Muslim hero”, while Ma Rulong defected to the Qing.[20] On multiple occasions Kunming was attacked and sacked by Du Wenxiu’s forces.[21][22] His capital was Dali.[23] The revolt ended in 1873.[24] Du Wenxiu is regarded as a hero by the present day government of China.[25] Du Wenxiu has recorded issued call for the complete expulsion of the Manchus from all of China in order for China to come under Chinese rule once again.[19] During this insurrection, Dun Wenxiu has released a slogan:

【参考译文】杜文秀公开宣称,他的目标是驱逐满族,统一汉族,消灭那些支持清朝的人。[14] 杜文秀并没有将屠杀回族归咎于汉族,相反,他将屠杀归咎于满族政权,称满族对中国来说是外来民族,他们疏远了汉族和其他少数民族。[15][16] 杜文秀经常使用反满言论,他进一步试图说服汉族和回族联合起来,在满清统治 200 年后推翻满清。[17][18] 杜文秀邀请同为回族的穆斯林领袖马如龙与他一起驱逐满清并“恢复中国”。[19] 杜文秀因为反抗满族“压迫”而“成为穆斯林英雄”,而马如龙则投奔了清朝。[20] 昆明曾多次遭到杜文秀军队的攻击和洗劫。[21][22]他的首都是大理。[23] 起义于 1873 年结束。[24] 杜文秀被现中国政府视为英雄。[25] 杜文秀曾发出呼吁,要求将满族人彻底驱逐出中国,以便中国再次受到中国的统治。[19] 在这次起义中,杜文秀发布了这样一句口号:

To bring peace to Han, Down with the Qing court. (Chinese: 安漢反清)[26]

【参考译文】安汉反清[26]

Albert Fytche opined this revolt was not religious in nature, since the Muslims were joined by the non-Muslim Shan and Kakhyen and other hill tribes.[27] Modern historian Jingyuan Qian shared this view.[13] Fytche reported this testimony from a British officer, and he also stated that the Chinese were tolerant of different religions so they were unlikely to have caused the revolt by interfering in the practice of Islam.[28] In addition, loyalist Muslim forces helped Qing crush the rebel Muslims.[29] Instead, the discrimination by China’s imperial administration against the Hui caused their rebellions.[30] James Hastings wrote in Volume 8 of the Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics that the Panthay Revolt was set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than due to Islam and religion.[31]

【参考译文】艾伯特·费奇认为这场起义与宗教无关,因为穆斯林与非穆斯林的掸族、卡钦族和其他山地部落联合起来。[27] 现代历史学家钱敬远也持同样的观点。[13] 费奇记录了一名英国军官的证词,他还表示,中国人对不同宗教持宽容态度,因此他们不太可能通过干涉伊斯兰教活动而引发起义。[28] 此外,效忠的穆斯林部队帮助清朝镇压了叛乱的穆斯林。[29] 相反,中国帝国政府对回族的歧视导致了他们的叛乱。[30] 詹姆斯·黑斯廷斯在《宗教与伦理百科全书》第 8 卷中写道,潘塞起义是由种族对抗和阶级战争引发的,而不是由于伊斯兰教和宗教。[31]

However, some sources suggest that the Panthay Rebellion originated solely as a conflict between Han and Hui miners in 1853, despite Han-Hui tension existing for decades prior to the event, including a three-day massacre of Hui by Han and Qing officials in 1845. Hui and Han were regarded and classified by Qing as two different ethnic groups, with Hui not seen as an exclusively religious classification.[citation needed]

【参考译文】然而,一些资料表明,班塞起义仅仅起源于 1853 年汉族和回族矿工之间的冲突,尽管在班塞起义之前,汉族和回族之间的紧张关系已经存在了几十年,包括 1845 年汉族和清朝官员对回族进行的为期三天的大屠杀。清朝将回族和汉族视为两个不同的民族,回族并不被视为一个独有的宗教类别。[需要引证]

2. 战争的起因 | Course of the war

图片题注:杜文秀所用印,左侧为阿拉伯语“Qa’id jami al-muslimin”,意为“穆民的指挥官卡迪”,右侧为汉文篆字“总统兵马大元帅杜”

图片来源:Emile Rocher

图片题注:杜文秀使用的旗帜

图片来源:Unknown. File originally by Samhanin

咸丰六年(1856年),临安府(治所在今建水县)因矿权纠纷发生汉、回冲突,冲突蔓延到昆明等地。云南巡抚下令对“滋事”回民,格杀无论。此举激起云南各地回民的反抗。8月,杜文秀在蒙化(今巍山彝族回族自治县)小围埂村聚众起义。叛军攻克大理,并以此为根据地建立政权,杜文秀任“总统兵马大元帅”,宣传响应太平天国,建立大理政权,废除清朝年号,制定“遥奉太平天国南京号召,革命满清”和“联合回汉一体,竖立义旗,驱逐鞑虏,恢复中华,剪除贪污,出民水火”的纲领,规定各民族之间一律平等的原则[2]。

The rebellion started as widespread local uprisings in virtually every region of the province. It was the rebels in western Yunnan under the leadership of Du Wenxiu who, by gaining control of Dali in 1856 (which they retained until its fall in 1872), became the major military and political center of opposition to the Qing government. Upon taking power, Du Wenxiu promised that he would ally with the Taiping Rebellion, which also aimed to overthrew the Qing dynasty.[32] The rebels captured the city of Dali, which became the base for their operations, and they declared themselves a separate political entity from China. The rebels identified their nation as Pingnan Guo (Ping-nan Kuo; simplified Chinese: 平南国; traditional Chinese: 平南國; lit. ‘Pacified Southern State’).[33] Tribal pagan animism, Confucianism, and Islam were all legalized and “honoured” with a “Chinese-style bureaucracy” in Du Wenxiu’s Sultanate. A third of the Sultanate’s military posts were filled with Han Chinese, who also filled the majority of civil posts.[34] Du Wenxiu wore Chinese clothing, and he mandated the use of the Arabic language by his regime.[35][36] Du also banned pork.[37] Ma Rulong also banned pork in areas under his control after he surrendered and joined the Qing forces.[38]

【参考译文】叛乱始于云南省几乎所有地区爆发的大规模地方起义。1856 年,杜文秀领导的云南西部叛军夺取了大理的控制权(直到 1872 年大理沦陷),成为反清政府的主要军事和政治中心。杜文秀掌权后承诺与太平天国结盟,太平天国也旨在推翻清朝。[32] 叛军占领了大理市,将其作为行动基地,并宣布自己是独立于中国的政治实体。叛军自称其国家为平南国。[33]在杜文秀的苏丹国,部落异教万物有灵论、儒教和伊斯兰教都合法化了,并被“尊崇为”中国式的官僚机构。苏丹国三分之一的军事职位由汉人担任,大多数民事职位也由汉人担任。[34]杜文秀身着汉服,并要求政权使用阿拉伯语。[35][36]杜文秀还禁止吃猪肉。[37]马如龙投降并加入清军后,也在他控制的地区禁止吃猪肉。[38]

The Imperial government was hindered by a profusion of problems in various parts of the sprawling empire, including the Taiping rebellion. China was also still suffering from the shocks caused by the first series of unequal treaties, such as the Treaty of Nanking. These circumstances favored the ascendancy of the Muslims in Yunnan. A total war was waged against Manchu rule. Du Wenxiu refused to surrender, unlike the other rebellious Muslim commander, Ma Rulong.[39]

【参考译文】帝国政府受到庞大帝国各地区大量问题的困扰,包括太平天国起义。中国还遭受着第一批不平等条约(如《南京条约》)带来的冲击。这些情况有利于云南穆斯林的崛起。一场反对满族统治的全面战争开始了。杜文秀拒绝投降,这与另一名叛乱的穆斯林指挥官马如龙不同。[39]

2.1 谈判 | Negotiations

During the revolt, Hui from provinces which were not in rebellion, like Sichuan and Zhejiang, served as negotiators between rebellious Hui and the Qing government. One of Du Wenxiu’s banners read “Deprive the Manchu Qing of their Mandate to Rule” (革命滿清), and he called on Han to assist Hui in their attempt to overthrow the Manchu regime and drive the Manchus out of China.[40] Du’s forces led multiple non-Muslim forces, including Han Chinese, Li, Bai, and Hani.[41]

【参考译文】起义期间,四川和浙江等未发生叛乱的省份的回民充当了叛乱回民和清政府之间的谈判代表。杜文秀的一条横幅上写着“革命满清”,他呼吁汉族人协助回民推翻满族政权,将满族人赶出中国。[40] 杜文秀的部队领导了多支非穆斯林部队,包括汉族、黎族、白族和哈尼族。[41]

2.2 “平定”的南方王国 | The “Pacified” Southern Kingdom

图片题注:Momien during the Pingnan Kingdom, from Colonel Sladen and Browne

参考译文:屏南国时期的莫米恩,斯莱登上校和布朗所著

图片来源:Internet Archive Book Images

The Manchus had secretly hounded mobs on to the rich Panthays, provoked anti-Hui riots and instigated destruction of their mosques.[42] The rebels were joined by non-Muslim Shan and Kachin people and other hill tribes in the revolt.[27] Du’s forces led multiple non-Muslim forces, including Li, Bai, and Hani.[41] loyalist Muslim forces helped Qing in their effort to pacify rebellions.[29] They wrested one important city after another from the hands of the imperial mandarins. The Chinese towns and villages that resisted were pillaged, and the male populations there were massacred. All the places that yielded were spared.[42] The ancient holy city of Dali fell to the Panthays in 1857. With the capture of Dali, Muslim supremacy became an established fact in Yunnan.[14] This may have had something to do with the sects of Islam practiced among the rebels. The Gedimu Hanafi Sunni Muslims under Ma Rulong readily defected to Qing, while the Jahriyya Sufi Muslims did not surrender. Some of the Jahriyya rebels in the Panthay Rebellion like Ma Shenglin were related to the Dungan revolt Jahriyya leader Ma Hualong and maintained contact with them.

【参考译文】满族人秘密地将暴徒赶入富裕的潘塞人(回族)部落,挑起反回民暴乱,并煽动他们摧毁清真寺。[42] 非穆斯林的掸族、克钦族和其他山地部落也加入了叛乱。[27] 杜的军队领导了多支非穆斯林军队,其中包括黎族、白族和哈尼族。[41] 效忠清朝的穆斯林军队帮助清朝平定叛乱。[29] 他们从清朝官员手中夺取了一座又一座重要城市。抵抗的中国城镇和村庄遭到洗劫,那里的男性人口遭到屠杀。所有屈服的地方都得以幸免。[42] 1857 年,古老的圣城大理落入潘塞人手中。随着大理被攻占,穆斯林至上成为云南的既定事实。[14]这可能与叛军信奉的伊斯兰教派有关。马如龙领导下的格迪木哈乃斐派逊尼派穆斯林很快投奔清朝,而哲赫里亚苏菲派穆斯林则没有投降。潘塞叛乱中的一些哲赫里亚叛军,如马胜林,与东干叛乱哲赫里亚领袖马化龙有亲属关系,并与他们保持着联系。

The eight years from 1860 to 1868 were the heyday of the Sultanate. The Panthays had either taken or destroyed forty towns and one hundred villages.[43] During this period the Sultan Suleiman, on his way to Mecca as a pilgrim, visited Rangoon, presumably via the Kengtung route, and from there to Calcutta where he had a chance to see the British in India.[44]

【参考译文】1860 年至 1868 年的八年间是苏丹国的鼎盛时期。潘塞叛军占领或摧毁了四十座城镇和一百个村庄。[43] 在此期间,苏丹苏莱曼以朝圣者的身份前往麦加,他访问了仰光,大概是通过景栋路线,然后从那里前往加尔各答,在那里他有机会见到了在印度的英国人。[44]

同治六年(1867年),杜文秀政权已占有云南一半的地区。同年杜文秀派二十万大军包围昆明,但久攻不下。

2.3 衰退 | Decline

The Sultanate’s power declined after 1868. The Chinese Imperial government had succeeded in reinvigorating itself.[clarification needed] By 1871 it was directing a campaign for the annihilation of the obdurate Hui Muslims of Yunnan. By degrees the Imperial government had tightened the cordon around the Sultanate. The Sultanate proved unstable as soon as the Imperial government made a regular and determined attack on it. Town after town fell under well-organized attacks from imperial troops. Dali itself was besieged by imperial forces. Sultan Sulayman (also spelt Suleiman) found himself caged in by the walls of his capital. Desperately looking for outside help, he turned to the British for military assistance.[45] He realized that only British military intervention could have saved his Sultanate.[citation needed]

【参考译文】1868 年后,苏丹国的权力开始衰落。中国帝国政府成功地重振了自身。[需要澄清] 1871 年,它发起了一场消灭云南顽固回族穆斯林的运动。帝国政府逐渐加强了对苏丹国的封锁。一旦帝国政府定期对苏丹国发动坚决的攻击,苏丹国就会变得不稳定。一个又一个城镇遭到帝国军队精心组织的攻击。大理本身被帝国军队围困。苏丹苏莱曼 (也拼作苏莱曼) 发现自己被困在首都的城墙里。他迫切地寻求外界帮助,于是向英国寻求军事援助。[45] 他意识到只有英国的军事干预才能拯救他的苏丹国。[需要引证]

同治八年(1869年)清军反攻,叛军失利,退回滇西,这次失利成为叛乱失败的转折点。

The Sultan had reasons for turning to the British. British authorities in India and British Burma had sent a mission led by Major Sladen to the town of Tengyue in present-day Yunnan (known as Momien in the Shan language) from May–July 1868.[46] The Sladen mission had stayed seven weeks at Momien meeting with rebel officials. The main purpose of the mission was to revive the Ambassadorial Route between Bhamo and Yunnan and resuscitate border trade, which had almost ceased since 1855, mainly because of the Yunnan Muslims’ rebellion.

【参考译文】苏丹向英国求助是有原因的。 1868 年 5 月至 7 月,英国驻印度和英属缅甸当局派遣斯莱登少校率领的使团前往今云南的腾越镇(掸语中称为莫缅)。[46]斯莱登使团在莫缅停留了七周,与叛军官员会面。使团的主要目的是恢复八莫和云南之间的使节路线,恢复自 1855 年以来几乎停止的边境贸易,这主要是因为云南穆斯林的叛乱。

Taking advantage of the friendly relations resulting from Sladen’s visit, Sultan Sulayman, in his fight for the survival of the Pingnan Guo Sultanate, turned to the British Empire for formal recognition and military assistance. In 1872 he sent his adopted son Prince Hassan to England with a personal letter to Queen Victoria, via Burma, in an attempt to obtain official recognition of the Panthay Empire as an independent power.[47] The Hassan Mission was accorded courtesy and hospitality in both British Burma and England. However, the British politely but firmly refused to intervene militarily in Yunnan against Peking.[45] In any case the mission came too late—while Hassan and his party were abroad, Dali was captured by Imperial troops in January 1873.

【参考译文】苏丹苏莱曼利用斯莱登访问后建立的友好关系,为平南郭苏丹国的生存而战,向英国寻求正式承认和军事援助。1872 年,他派养子哈桑王子经缅甸前往英国,并向维多利亚女王寄送了一封私人信件,试图获得官方承认平南郭苏丹国为独立政权。[47]哈桑使团在英属缅甸和英国都受到了礼遇和款待。然而,英国人礼貌而坚定地拒绝在云南对北京进行军事干预。[45] 无论如何,使团来得太晚了——当哈桑一行人在国外时,大理于 1873 年 1 月被帝国军队占领。

同治十一年(1872年),清军围困大理,杜文秀服毒自杀,叛乱失败。

The Imperial government had waged an all-out war against the Sultanate with the help of French artillery experts.[45] The ill-equipped rebels with no allies were no match for their modern equipment, trained personnel and numerical superiority. Thus, within two decades of its rise, the power of the Panthays in Yunnan fell. Seeing no escape and no mercy from his relentless foe, Sultan Sulayman tried to take his own life before the fall of Dali. However, before the opium he drank took full effect, he was beheaded by his enemies.[48][49][50][51] Manchu troops then began a massacre of the rebels, killing thousands of civilians, sending severed ears along with the heads of their victims.[52] His body is entombed in Xiadui outside of Dali.[53] The Sultan’s head was preserved in honey and dispatched to the Imperial Court in Peking as a trophy and a testimony to the decisive nature of the victory of the Imperial Manchu Qing over the Muslims of Yunnan.[54]

【参考译文】帝国政府在法国炮兵专家的帮助下对苏丹国发动了一场全面战争。[45] 装备简陋、没有盟友的叛军无法与现代装备、训练有素的人员和数量优势相抗衡。因此,在崛起后的二十年内,云南的潘塞派势力衰落了。苏丹苏莱曼看到无路可逃,也见不到无情的敌人的怜悯,于是试图在大理沦陷前自杀。然而,在他喝下的鸦片完全发挥作用之前,他被敌人斩首了。[48][49][50][51]满族军队随即开始对叛军进行大屠杀,杀死了数千名平民,受害者的耳朵和头颅都被割下。[52] 他的尸体被埋葬在大理郊外的下堆。[53] 苏丹的头颅被浸泡在蜂蜜中,并作为战利品送往北京朝廷,以证明满清帝国对云南穆斯林取得了决定性的胜利。[54]

One of the Muslim generals, Ma Rulong (Ma Julung), defected to the Qing side.[55] He then helped the Qing forces crush his fellow Muslim rebels.[56][57][58] He was called Marshal Ma by Europeans and acquired almost total control of Yunnan province.[59]

【参考译文】一名穆斯林将军马如龙 (Ma Juung) 叛逃到清朝一方。[55] 随后,他帮助清军镇压了其他穆斯林叛军。[56][57][58] 欧洲人称他为马元帅,并几乎完全控制了云南省。[59]

In the 1860s, when Ma Rulong in central and west Yunnan, fought to crush the rebel presence to bring the area under Qing control, a great-uncle of Ma Shaowu Ma Shenglin defended Greater Donggou against Ma Rulong’s army. Ma Shenglin was the religious head of the Jahriyya menhuan in Yunnan and a military leader. A mortar killed him during the battle in 1871.[60]

【参考译文】19 世纪 60 年代,马如龙在云南中部和西部与叛军展开战斗,试图将该地区纳入清朝统治,马绍武的叔祖父马胜林保卫了大东沟,抵抗马如龙的军队。马胜林是云南哲合忍耶门宦的宗教领袖和军事领袖。他在 1871 年的战斗中被迫击炮击毙。[60]

Scattered remnants of the Pingnan Guo troops continued their resistance after the fall of Dali, but when Momien was next besieged and stormed by imperial troops in May 1873, their resistance broke completely. Gov. Ta-sa-kon was captured and executed by order of the Imperial government.

【参考译文】大理沦陷后,平南国军队的零星残余继续抵抗,但当 1873 年 5 月莫缅再次遭到清朝军队围攻时,他们的抵抗被彻底瓦解。达沙贡总督被捕,并被清朝政府下令处决。

3. 后果 | Aftermath

3.1 暴行 | Atrocities

Though largely forgotten, the bloody rebellion caused the deaths of up to a million people in Yunnan. Many adherents to the Yunnanese Muslim cause were persecuted by the imperial Manchus. Wholesale massacres of Yunnanese Muslims followed. Many fled with their families across the Burmese border and took refuge in the Wa State where, about 1875, they set up the exclusively Hui town of Panglong.[61]

【参考译文】虽然人们大多已淡忘,但这场血腥的叛乱却导致云南多达 100 万人丧生。许多支持云南穆斯林事业的信徒遭到满清帝国的迫害。随后,云南穆斯林遭到大规模屠杀。许多人带着家人越过缅甸边境,在佤邦避难。大约 1875 年,他们在那里建立了回族聚居的彬龙镇。[61]

For a period of perhaps ten to fifteen years following the collapse of the Panthay Rebellion, the province’s Hui minority was widely discriminated against by the victorious Qing, especially in the western frontier districts contiguous with Burma. During these years the refugee Hui settled across the frontier within Burma gradually established themselves in their traditional callings – as merchants, caravaneers, miners, restaurateurs and (for those who chose or were forced to live beyond the law) as smugglers and mercenaries and became known in Burma as the Panthay.

【参考译文】在潘塞起义失败后的大约 10 到 15 年时间里,该省的回族少数民族遭到了胜利的清朝的广泛歧视,尤其是在与缅甸接壤的西部边境地区。在这些年里,流亡在缅甸边境的回族逐渐确立了自己的传统职业——商人、商队、矿工、餐馆老板,以及(对于那些选择或被迫生活在法律之外的人来说)走私者和雇佣兵,并在缅甸被称为潘塞。

At least 15 years after the collapse of the Panthay Rebellion, the original Panthay settlements in Burma had grown to include numbers of Shan and other hill peoples.

【参考译文】在潘塞起义失败至少 15 年后,缅甸境内原来的潘塞定居点已发展壮大,其中包括大量掸族和其他山地民族。

Panglong, a Chinese Muslim town in British Burma, was entirely destroyed by the Japanese invaders in the Japanese invasion of Burma.[62] The Hui Muslim Ma Guanggui became the leader of the Hui Panglong self-defense guard created by Su who was sent by the Kuomintang government of the Republic of China to fight against the Japanese invasion of Panglong in 1942. The Japanese destroyed Panglong, burning it and driving out the over 200 Hui households out as refugees. Yunnan and Kokang received Hui refugees from Panglong driven out by the Japanese. One of Ma Guanggui’s nephews was Ma Yeye, a son of Ma Guanghua and he narrated the history of Panglang included the Japanese attack.[63] An account of the Japanese attack on the Hui in Panglong was written and published in 1998 by a Hui from Panglong called “Panglong Booklet”.[64] The Japanese attack in Burma caused the Hui Mu family to seek refuge in Panglong but they were driven out again to Yunnan from Panglong when the Japanese attacked Panglong.[65]

【参考译文】盘龙是英属缅甸的一个中国穆斯林城镇,在日本入侵缅甸时被日军彻底摧毁。[62] 回族穆斯林马光贵成为回族盘龙自卫队的队长,该队由苏志雄组建,苏志雄于 1942 年受中华民国国民党政府派遣,前往抗击日军入侵盘龙。日军摧毁了盘龙,烧毁了盘龙,并将 200 多户回民赶出,成为难民。云南和果敢接收了被日本人赶出的盘龙回民难民。马光贵的侄子马业业是马光华的儿子,他讲述了盘龙的历史,包括日军的进攻。[63] 1998 年,一名来自盘龙的回民撰写并出版了一本关于日军袭击盘龙回民的记录,名为《盘龙小册子》。[64]日军进攻缅甸,迫使惠木一家到彬龙寻求庇护。但当日军进攻彬龙时,他们又被赶出彬龙,前往云南。[65]

3.2 对穆斯林的影响 | Impact on Muslims

The Qing dynasty did not massacre Muslims who surrendered, in fact, Muslim General Ma Rulong, who surrendered and join the Qing campaign to crush the rebel Muslims, was promoted, and among Yunnan’s military officers serving the Qing, he was the strongest.[59][60]

【参考译文】清朝并没有屠杀投降的穆斯林,事实上,投降并加入清朝镇压叛乱穆斯林的行动的穆斯林将军马如龙得到了提拔,他是云南为清朝服务的军官中实力最强的。[59][60]

The Qing armies left alone Muslims who did not revolt like in Yunnan’s northeast prefecture of Zhaotong where there was a big Muslim population density after the war.[66]

【参考译文】清军放过了没有叛乱的穆斯林,就像战后云南东北部昭通府穆斯林人口密集的地方一样。[66]

The use of Muslims in the Qing armies against the revolt was noted by Yang Zengxin.[67]

【参考译文】杨增新注意到清军使用穆斯林镇压叛乱。[67]

The third reason is that at the time that Turkic Muslims were waging rebellion in the early years of the Guangxu reign, the ‘five elite divisions’ that Governor-General Liu Jintang led out of the Pass were all Dungan troops (Chinese: 回队, romanized: Huí duì). Back then, Dungan military commanders such as Cui Wei and Hua Dacai were surrendered troops who had been redeployed. These are undoubtedly cases of pawns who went on to achieve great merit. When Cen Shuying was in charge of military affairs in Yunnan, the Muslim troops and generals that he used included many rebels, and it was because of them that the Muslim rebellion in Yunnan was pacified. These are examples to show that Muslim troops can be used effectively even while Muslim uprisings are still in progress. What is more, since the establishment of the Republic, Dungan have demonstrated not the slightest hint of errant behaviour to suggest that they may prove to be unreliable.

【参考译文】第三个原因是,光绪初年突厥穆斯林发动叛乱时,总督刘锦棠率领的“五支精锐部队”全部是东干部队(中文:回队,罗马化:Huí duì)。当时,崔炜和华达才等东干军将领都是重新部署的投降部队。毫无疑问,这些都是马前卒立下大功的例子。岑树英在云南掌管军事事务时,他所用的回民军队和将领中就包括许多叛军,正是由于他们的帮助,云南的回民叛乱才得以平息。这些例子表明,即使在回民起义仍在进行中时,回民军队也可以得到有效利用。更重要的是,自民国成立以来,东干人没有表现出丝毫不可靠的行为迹象。

3.3 对缅甸的影响 | Impact on Burma

The rebellion had a significant negative impact on the Konbaung dynasty. After ceding lower Burma to the British following the First Anglo-Burmese War, Burma lost access to vast tracts of rice-growing land. Not wishing to upset China, the Burmese kingdom agreed to refuse trade with the Pingnan Guo rebels in accordance with China’s demands. Without the ability to import rice from China, Burma was forced to import rice from India. In addition, the Burmese economy had relied heavily on cotton exports to China, and suddenly lost access to the vast Chinese market. Many surviving Hui refugees escaped over the border to neighboring countries, Burma, Thailand and Laos, forming the basis of a minority Chinese Hui population in those nations.

【参考译文】叛乱对贡榜王朝产生了重大的负面影响。在第一次英缅战争后,缅甸将下缅甸割让给英国,失去了大片稻米种植地。缅甸王国不想惹怒中国,同意按照中国的要求拒绝与平南国叛军进行贸易。由于无法从中国进口大米,缅甸被迫从印度进口大米。此外,缅甸经济原本严重依赖对华棉花出口,而突然失去广阔的中国市场,大量幸存的回族难民越过边境逃往邻国缅甸、泰国、老挝,成为这些国家中国少数回族人口的基础。

A. 参见(维基百科的相关词条)| See also

- Third plague pandemic / 第三次鼠疫大流行

- Panthay / 潘泰人

- Islam in China【伊斯兰教在中国】

- Islam during the Qing dynasty【清代伊斯兰教】

- Islamophobia in China【中国的伊斯兰恐惧症】

- Yusuf Ma Dexin, a prominent Muslim scholar in Yunnan at the time of the rebellions【优素福·马德新,叛乱时期云南著名的穆斯林学者】

- Taiping Rebellion【太平天国运动】

- Nian Rebellion【捻乱】

- Miao Rebellion (1854–1873)【苗族叛乱(1854年–1873年)】

- Nepalese-Tibetan War【尼藏战争】

- Dungan revolt (1862–1877)【东干起义 (同治回乱,1862–1877)】

- Punti–Hakka Clan Wars【土客械斗】

- 沙甸事件

- 班弄

B. 英文词条参考文献

B1. 引用列表(与文中标号对应)| References

This article incorporates text from Burma past and present, by Albert Fytche, a publication from 1878, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Burma past and present, by Albert Fytche, a publication from 1878, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916, now in the public domain in the United States.

- ^ Scott 1900, p. 607

- ^ Yule & Burnell 1968, p. 669

- ^ Notar, Beth (2001). “Du Wenxiu and the Politics of the Muslim Past”. Twentieth-Century China. 26 (2): 64–94. doi:10.1179/tcc.2001.26.2.64. S2CID 145702898.

- ^ R. Keith Schoppa (2002). Revolution and its past: identities and change in modern Chinese history. Prentice Hall. p. 79. ISBN 0-13-022407-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Fairbank 1980, p. 213.

- ^ Schoppa, R. Keith (2008). East Asia: identities and change in the modern world, 1700-present (illustrated ed.). Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 58. ISBN 978-0132431460. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Atwill 2005, p. 89.

- ^ Wellman, James K. Jr., ed. (2007). Belief and Bloodshed: Religion and Violence across Time and Tradition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 121. ISBN 978-0742571341.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (2014). The Islam Quintet: Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree, The Book of Saladin, The Stone Woman, A Sultan in Palermo, and Night of the Golden Butterfly. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1480448582.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (2010). Night of the Golden Butterfly (Vol. 5) (The Islam Quintet). Verso Books. p. 90. ISBN 978-1844676118.

- ^ Elleman, Bruce A. (2001). Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 64. ISBN 0415214734. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Fairbank 1980, pp. 213–.

- ^ Qian, Jingyuan (2014). “Too Far from Mecca, Too Close to Peking: The Ethnic Violence and the Making of Chinese Muslim Identity, 1821-1871”. History Honors Projects. 27: 37.

- ^ Chesneaux, Bastid & Bergère 1976, p. 114.

- ^ Association of Muslim Social Scientists, International Institute of Islamic Thought (2006). The American journal of Islamic social sciences, Volume 23, Issues 3-4. AJISS. p. 110. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Jacob Tyler Whittaker (1997). Du Wenxiu’s Partial Peace: Framing Alternatives to Manchu Rule Across Ethnic Boundaries Among China’s Nineteenth-century Rebel Movements. University of California, Berkeley. p. 38.

- ^ Dillon 1999, p. 59.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (2012). China: A Modern History (reprint ed.). I.B.Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 978-1780763811. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Atwill 2005, p. 120.

- ^ Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan) (1993). Asian Research Trends, Volumes 3-4. Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies. p. 137. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Mansfield, Stephen (2007). China, Yunnan Province. Compiled by Martin Walters (illustrated ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. p. 69. ISBN 978-1841621692. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Damian Harper (2007). China’s Southwest. Regional Guide Series (illustrated ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 223. ISBN 978-1741041859. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Giersch, Charles Patterson (2006). Asian Borderlands: The Transformation of Qing China’s Yunnan Frontier (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 217. ISBN 0674021711. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Mosk, Carl (2011). Traps Embraced Or Escaped: Elites in the Economic Development of Modern Japan and China. World Scientific. p. 62. ISBN 978-9814287524. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Comparative Civilizations Review, Issues 32-34. 1995. p. 36. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ 王钟翰 2010

- ^ Fytche 1878, p. 300

- ^ Fytche 1878, p. 301

- ^ Joseph Mitsuo Kitagawa (2002). The religious traditions of Asia: religion, history, and culture. Routledge. p. 283. ISBN 0-7007-1762-5. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Atwill 2005

- ^ James Hastings; John Alexander Selbie; Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. EDINBURGH: T. & T. Clark. p. 893. ISBN 9780567065094. Retrieved 28 November 2010.(Original from Harvard University)

- ^ Chesneaux, Bastid & Bergère 1976, p. 120.

- ^ http://www.shijiemingren.com/doc-view-27181.html Archived 17 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 31 Mar 2017

- ^ Fairbank 1980, pp. 214–.

- ^ Journal of Southeast Asian studies, Volume 16. McGraw-Hill Far Eastern Publishers. 1985. p. 117. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Journal of Southeast Asian studies, Volume 16. McGraw-Hill Far Eastern Publishers. 1985. p. 117. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Journal of Southeast Asian studies, Volume 16. McGraw-Hill Far Eastern Publishers. 1985. p. 127. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Atwill 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan) (1993). Asian research trends, Volumes 3-4. Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies. p. 137. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Dillon 1999, p. 59; Atwill 2005, p. 139.

- ^ International Arts and Sciences Press, M.E. Sharpe, Inc (1997). Chinese studies in philosophy, Volume 28. M. E. Sharpe. p. 67. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ (Anderson, 1876, 233)

- ^ (Anderson, 1876, 343)

- ^ (Anderson, 1876, 242)

- ^ Thaung 1961, p. 481

- ^ John Anderson; Edward Bosc Sladen; Horace Albert Browne (1876). Mandalay to Momien: A Narrative of the Two Expeditions to Western China of 1868 and 1875, Under Col. Edward B. Sladen and Col. Horace Browne. Macmillan and Company. p. 189.

- ^ “The Chinese in Central Asia”. Pall Mall Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 19 December 1876. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Myint-U 2007, pp. 145, 172.

- ^ Myint-U, Thant (2012). Where China Meets India: Burma and the New Crossroads of Asia (illustrated, reprint ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 978-0374533526. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ White, Matthew (2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History (illustrated ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 298. ISBN 978-0393081923. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Cooke, Tim, ed. (2010). The New Cultural Atlas of China. Contributor Marshall Cavendish Corporation. Marshall Cavendish. p. 38. ISBN 978-0761478751. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Myint-U 2007, p. 172.

- ^ Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan) (1993). Asian Research Trends, Volumes 3-4. Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies. p. 136. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Thaung 1961, p. 482

- ^ de Kavanagh Boulger 1893, p. 319

- ^ Davenport Northrop 1894, p. 130

- ^ Littell & Littell 1900, p. 757

- ^ Holmes Agnew & Hilliard Bidwell 1900, p. 620

- ^ de Kavanagh Boulger 1898, p. 443

- ^ Garnaut 2008

- ^ Scott 1900, p. 740

- ^ Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (December 2015). “‘Saharat Tai Doem’ Thailand in Shan State, 1941–45”. CPA Media.

- ^ Chang 2015, pp. 122–.

- ^ Chang 2015, pp. 124–.

- ^ Chang 2015, pp. 129–.

- ^ Dillon 1999, p. 77

- ^ Garnaut 2008, pp. 104–105.

B2. 来源文献 | Bibliography

- Atwill, David G. (2005), The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856-1873, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-5159-5

- Chang, Wen-Chin (16 January 2015). Beyond Borders: Stories of Yunnanese Chinese Migrants of Burma. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-5450-9.

- Chesneaux, Jean; Bastid, Marianne; Bergère, Marie-Claire (1976). China from the opium wars to the 1911 revolution. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-49213-7.

- Davenport Northrop, Henry (1894), “The flowery kingdom and the land of the Mikado, or, China, Japan and Corea”, Making of America Project, London, CA-ON: J.H.Moore Co. Inc., retrieved 28 June 2010

- Dillon, Michael (26 July 1999), China’s Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects, Richmond, UK: Routledge / Curzon Press, ISBN 0-7007-1026-4, retrieved 28 June 2010

- Fairbank, John King (1980). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800-1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- Fitzgerald, Charles Patrick (1996), Southern Expansion of the Chinese People: Southern Fields and Southern Ocean, Thailand: White Lotus Co., ISBN 974-8495-81-7

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011). Traders of the Golden Triangle. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B006GMID5K

- Fytche, Albert (1878), Burma past and present, LONDON: C. K. Paul & co., retrieved 28 June 20109=(Original from Harvard University)

- de Kavanagh Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1893), A Short History of China: Being an Account for the General Reader of an Ancient Empire and People, W. H. Allen & co., retrieved 28 June 2010

- de Kavanagh Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1898), The History of China, vol. 2, W. Thacker & co., retrieved 28 June 2010

- Myint-U, Thant (2007). The River of Lost Footsteps: Histories of Burma. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0374707903. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Scott, J. George (1900), “i”, GUBSS 1, Rangoon Government Printing

- Thant, Myint-U (2001), The Making of Modern Burma, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-78021-6

- Thaung, Dr (1961), “Panthay Interlude in Yunnan: A Study in Vicissitudes Through the Burmese Kaleidoscope”, JBRS Fifth Anniversary Publications No. 1, Rangoon Sarpy Beikman

- Yule, Col. Henry; Burnell, A.C. (1968) [1886 (1st ed. Murray, London)], Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical And Discursive, Munshiran Manoharlal (reprint)

Essays, studies

- Garnaut, Anthony (2008), From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals (PDF), Etudes orientales N°25, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012, retrieved 14 July 2010

Articles (in journals, magazines etc.)

- “Contemporary Review”, Religious toleration in China, vol. 86, July 1904

- Holmes Agnew, John; Hilliard Bidwell, Walter (1900), Eclectic Magazine, Leavitt, Throw and Co., retrieved 28 June 2010

- Littell, Eliakim; Littell, Robert S. (22 September 1900), “The Living Age”, Making of America Project, vol. 225, no. 2933, The Living Age Co. Inc., retrieved 28 June 2010

- 王钟翰 (2010), 中国民族史 [Han Chinese National History], GWculture.net, archived from the original on 26 May 2011, retrieved 28 June 2010 (in Chinese) [dead link]–>

C. 中文词条参考文献

- 鲜为人知的杜文秀起义:秀才造反捅开清廷大窟窿. 人民网. [2025-01-09]. (原始内容存档于2020-09-20).

- 李健彪. 《执著岁月: 回族史与伊斯兰文化》. 西安出版社. 2000.

- 辞海编纂委员会. 《辞海》(1999年版) (M) 1. 上海: 上海辞书出版社. 2000. ISBN 7-5326-0630-9.

D. 外部链接 | External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthay Rebellion.

分享到: