英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及根据名称精确检索已搬运的词条,请点击这里访问辽观网站。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

目录

0. 概述

【辽观注】此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

The term Southeast Asian Massif[1] was proposed in 1997 by anthropologist Jean Michaud[2] to discuss the human societies inhabiting the lands above an elevation of approximately 300 metres (1,000 ft) in the southeastern portion of the Asian landmass, thus not merely in the uplands of conventional Mainland Southeast Asia. It concerns highlands overlapping parts of 10 countries: southwest China, Northeast India, eastern Bangladesh, and all the highlands of Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Peninsular Malaysia, and Taiwan. The indigenous population encompassed within these limits numbers approximately 100 million, not counting migrants from surrounding lowland majority groups who came to settle in the highlands over the last few centuries.

【参考译文】1997年,人类学家让·米肖[2]提出了“东南亚高地[1]”一词,用以探讨居住在亚洲大陆东南部海拔约300米(1000英尺)以上地区的人类社会,因此,这不仅仅局限于传统东南亚大陆的高地地区。它涉及高地地区,这些地区横跨10个国家:中国西南部、印度东北部、孟加拉国东部以及缅甸(缅甸联邦共和国)、泰国、越南、老挝、柬埔寨、马来西亚半岛和台湾的所有高地。在这些地区范围内,原住民人口数量约为1亿,还不包括过去几个世纪里从周边低地主要族群迁来高地定居的移民。

The notion of the Southeast Asian Massif overlaps geographically with the eastern segment of Van Schendel’s notion of Zomia proposed in 2002,[3] while it overlaps geographically with what political scientist James C. Scott called Zomia in 2009.[4] While the notion of Zomia underscores a historical and political understanding of that high region, the Southeast Asian Massif is more appropriately labelled a place or a social space.

【参考译文】东南亚高地这一概念在地理上与范·申德尔(Van Schendel)2002年提出的“佐米亚”(Zomia)概念的东段有所重叠,[3]同时也与政治学家詹姆斯·C·斯科特(James C. Scott)2009年所称的佐米亚在地理上有所重叠。[4]虽然佐米亚这一概念强调了对这一高地地区的历史和政治理解,但东南亚高地更适合被视为一个地点或社会空间。

The Tibetan world is not included in the massif, as it has its own logic: a centralized and religiously harmonised core with a long, distinctive political existence that places it in a “feudal” and imperial category, which the societies historically associated with the massif have rarely, if ever, developed into.[6]

【参考译文】西藏地区并未被纳入这一高地范畴,因为它有其自身的逻辑:即以一个长期存在且独具特色的政治实体为核心,实现了宗教上的和谐统一,这使得它归入“封建”和帝国类别,而历史上与这一高地相关的社会很少,甚至从未发展出这样的形态。[6]

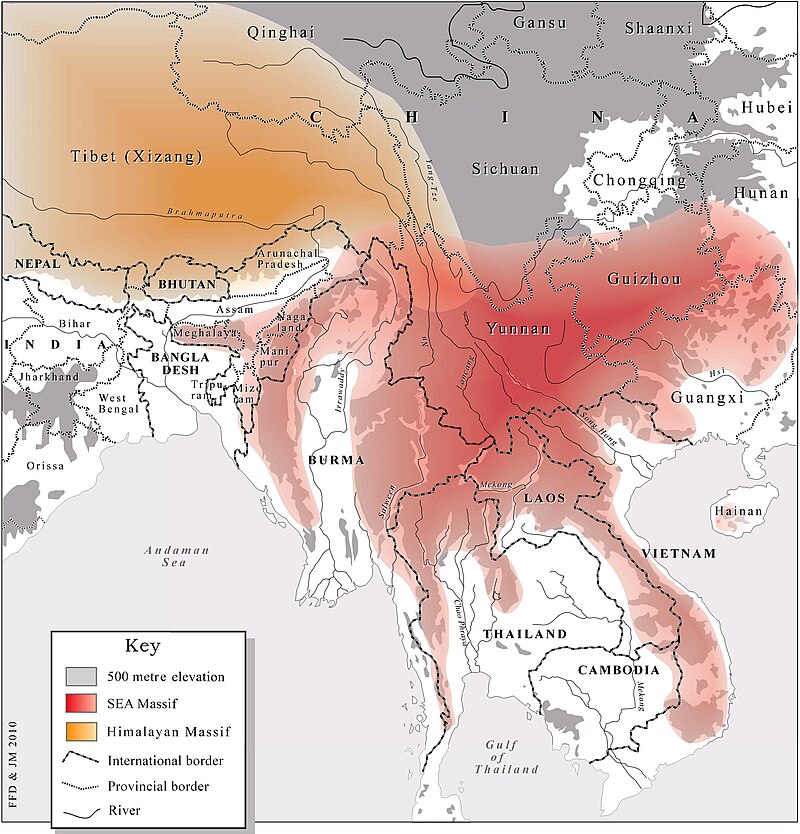

图片题注:The Southeast Asian Massif (in red) and part of the Himalayan Massif (in yellow). Gray background indicates land above 500 metres.

参考译文:东南亚高地(红色部分)和部分喜马拉雅高地(黄色部分)。灰色背景表示海拔500米以上的地区。

图片来源:Jean Michaud

1. 历史、语言和文化因素 | Historical, linguistic and cultural factors

To further qualify the particularities of the massif, a series of core factors can be incorporated: history, languages, religion, customary social structures, economies, and political relationships with lowland states. What distinguishes highland societies may exceed what they have in common: a vast ecosystem, a state of marginality, and forms of subordination. The massif is crossed by six major language families (Austroasiatic, Hmong–Mien, Kra–Dai, Sino-Tibetan, Indo-European, Austronesian), none of which forms a decisive majority. In religious terms, several groups are Animist, others are Buddhist, some are Christian, a good number share Taoist and Confucian values, the Hui are Muslim, the Kuki-Chin-speaking Bnei Menashe are Jewish, while most societies sport a complex syncretism. Throughout history, feuds and frequent hostilities between local groups were evidence of the plurality of cultures.[7] The region has never been united politically, not as an empire, nor as a space shared among a few feuding kingdoms, not even as a zone with harmonised political systems. Forms of distinct customary political organisations, chiefly lineage based versus “feudal“,[8] have long existed.

【参考译文】为了更全面地说明高地地区的特性,我们可以将一系列核心因素纳入考量:历史、语言、宗教、传统社会结构、经济与低地国家之间的政治关系。高地社会的独特性可能超出它们之间的共性:它们拥有庞大的生态系统、处于边缘地位以及存在从属形式。高地地区横跨六大语系(南岛语系、侗台语系、孟-高棉语系、汉藏语系、印欧语系、澳斯特罗-亚细亚语系),其中没有任何一个语系占据决定性多数。在宗教方面,一些群体信仰万物有灵论,另一些信仰佛教,有些信仰基督教,相当多的群体秉持道教和儒家价值观,回族信仰伊斯兰教,讲库基-钦语的比兴族(Bnei Menashe)信仰犹太教,而大多数社会则呈现出复杂的宗教融合现象。历史上,当地群体之间的争斗和频繁敌对行为证明了文化的多元性。[7]该地区从未实现过政治统一,既未形成帝国,也未成为几个争斗不休的王国共有的空间,甚至未成为政治制度和谐统一的区域。长期以来,一直存在着不同的传统政治组织形式,主要是基于血统的与“封建制”相对的组织形式。[8]

Along with other transnational highlands around the Himalayas and around the world, the Southeast Asian Massif is marginal and fragmented in historical, economic, as well as cultural terms. It may thus be seen as lacking the necessary significance in the larger scheme of things to be proposed as a promising area subdivision of Asian studies. However, it is important to rethink country based research when addressing trans-border and marginal societies.

【参考译文】与喜马拉雅山脉周围和世界各地的其他跨国高地一样,东南亚高地在历史、经济以及文化方面都处于边缘且分散的状态。因此,它可能被视为在亚洲研究这一更广泛的体系中缺乏必要的意义,不能作为一个有前景的地区细分。然而,在研究跨国和边缘社会时,重新思考以国家为基础的研究方法是非常重要的。

Inquiries on the ground throughout the massif show that these peoples share a sense of being different from the national majorities, a sense of geographical remoteness, and a state of marginality that is connected to political and economic distance from regional seats of power. In cultural terms, these highland societies are like a cultural mosaic with contrasting colours, rather than an integrated picture in harmonized shades – what Terry Rambo, talking from a Vietnam perspective, has dubbed “a psychedelic nightmare”.[9]

【参考译文】对整个高地地区的实地调查表明,这些民族有一种不同于国家主体民族的感觉,有一种地理上的偏远感,还有一种与区域权力中心在政治和经济上保持距离的边缘状态。从文化角度来看,这些高地社会就像一幅色彩对比鲜明的文化马赛克,而不是一幅和谐色调组成的完整画面——特里·兰博(Terry Rambo)从越南的角度称之为“迷幻噩梦”。[9]

Historically, these highlands have been used by lowland empires as reserves of resources (including slaves), and as buffer spaces between their domains.[10]

【参考译文】历史上,这些高地被低地帝国用作资源(包括奴隶)储备地,以及它们领土之间的缓冲区。[10]

2. “佐米亚”| Zomia

“Zomia” redirects here. For manga series, see Zomia (manga).

【参考译文】“佐米亚”一词跳转至此。对于同名漫画系列,请参见《佐米亚》(漫画)。

Zomia is a geographical term coined in 2002 by historian Willem van Schendel of the University of Amsterdam[11][12] to refer to the huge mass of mainland Southeast Asia that has historically been beyond the control of governments based in the population centers of the lowlands.[13] It largely overlaps with the geographical extent of the Southeast Asian Massif, although the exact boundaries of Zomia differ among scholars:[14] all would include the highlands of north Indochina (north Vietnam and all Laos), Thailand, the Shan Hills of northern Myanmar, and the mountains of Southwest China; some extend the region as far west as Tibet, Northeast India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. These areas share a common elevated, rugged terrain, and have been the home of ethnic minorities that have preserved their local cultures by residing far from state control and influence. Other scholars have used the term to discuss the similar ways that Southeast Asian governments have handled minority groups.[15]

【参考译文】佐米亚是阿姆斯特丹大学历史学家威廉·范·申德尔(Willem van Schendel)于2002年创造的一个地理术语,[11][12]用以指代历史上一直游离于低地人口中心政府控制之外的东南亚大陆广大地区。[13]它在很大程度上与东南亚高地的地理范围重叠,尽管学者们对佐米亚的确切边界存在分歧:[14]所有人都认为它包括印度支那北部(越南北部和整个老挝)、泰国、缅甸北部的掸邦高原以及中国西南部的山区;一些人则将这一区域向西延伸至西藏、印度东北部、巴基斯坦和阿富汗。这些地区拥有共同的高耸崎岖地形,是少数民族的聚居地,他们远离国家控制和影响,保留了当地文化。其他学者也使用该术语来讨论东南亚政府处理少数民族群体的相似方式。[15]

2.1 词源 | Etymology

The name is from Zomi, a term for highlander common to several related Tibeto-Burman languages spoken in the India-Bangladesh-Burma border area.[16]

【参考译文】该名称来源于“佐米”(Zomi),这是印度-孟加拉国-缅甸边境地区使用的几种相关藏缅语系语言中通用的高地人术语。[16]

2.2 詹姆斯·C·斯科特 | James C. Scott

Professor James C. Scott of Yale University used the concept of Zomia in his 2009 book The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia to argue that the continuity of the ethnic cultures living there provides a counter-narrative to the traditional story about modernity: namely, that once people are exposed to the conveniences of modern technology and the modern state, they will assimilate. Rather, the tribes in Zomia are conscious refugees from state rule and state-centered economies. From his preface:

【参考译文】耶鲁大学教授詹姆斯·C·斯科特(James C. Scott)在其2009年的著作《逃避统治的艺术:东南亚高地的无政府主义历史》中使用了佐米亚的概念,以论证生活在那里的民族文化的连续性为关于现代性的传统叙事提供了一种反叙事:即,一旦人们接触到现代技术和现代国家的便利,他们就会同化。相反,佐米亚的部落是有意识逃离国家统治和以国家为中心的经济体的难民。从他的前言中可以看到:

[Hill tribes] seen from the valley kingdoms as “our living ancestors”, “what we were like before we discovered wet-rice cultivation, Buddhism, and civilization [are on the contrary] best understood as runaway, fugitive, maroon communities who have, over the course of two millennia, been fleeing the oppressions of state-making projects in the valleys—slavery, conscription, taxes, corvée labor, epidemics, and warfare.

【参考译文】“[山谷王国眼中的山地部落]被视为‘我们活着的祖先’,‘我们在发现水稻种植、佛教和文明之前的模样’,但恰恰相反,他们最好被理解为是逃亡者、流浪者和隐居者群体,在过去两千年的时间里,他们一直在逃离山谷中建立国家项目所带来的压迫——奴隶制、征兵、税收、徭役、流行病和战争。”

Scott goes on to add that Zomia is the biggest remaining area of earth whose inhabitants have not been completely absorbed by nation-states, although that time is coming to an end. While Zomia is exceptionally diverse linguistically, the languages spoken in the hills are distinct from those spoken in the plains. Kinship structures, at least formally, also distinguish the hills from the lowlands. Hill societies do produce “a surplus”, but they do not use that surplus to support kings and monks. Distinctions of status and wealth abound in the hills, as in the valleys. The difference is that in the valleys they tend to be enduring, while in the hills they are both unstable and geographically confined.[17]

【参考译文】斯科特接着补充道,佐米亚是地球上最后一片尚未被民族国家完全吞并的广大地区,尽管这一天即将到来。虽然佐米亚在语言上极具多样性,但山地语言与平原语言截然不同。至少在形式上,亲属结构也将山地与低地区分开来。山地社会确实能“产生剩余”,但它们并不会用这些剩余来支持国王和僧侣。与山谷地区一样,山地地区也存在地位和财富的差异。不同之处在于,这些差异在山谷地区往往是持久的,而在山地地区则既不稳定又受地域限制。[17]

2.3 不同观点 | Differing perspectives

Jean Michaud explains the many dilemmas that arise from the language used to address the group of people residing in Zomia in his Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif.[18] The people of Zomia are often referred to as “national minority groups,” and Michaud argues that contention arises with each of these words. In regards to the word “national,” Michaud claims that the peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif are in fact transnational, as many groups span over several countries. According to Michaud, “minority” is not the legitimate way to label the group either, since the populations are so vast. Michaud even claims that the word “group” is problematic because of its connotation with community and “social cohesion” that not all groups share.[19][20]

【参考译文】让·米肖(Jean Michaud)在其著作《东南亚高地民族历史辞典》中解释了用何种语言来称呼居住在佐米亚的人群所带来的诸多困境。[18]佐米亚的居民通常被称为“少数民族”,而米肖认为这些词语中的每一个都存在问题。关于“民族”一词,米肖认为东南亚高地民族实际上是跨国的,因为许多群体跨越了几个国家。据米肖所言,“少数”一词也不是给该群体贴标签的合法方式,因为这些群体的人口数量庞大。米肖甚至声称“群体”一词也有问题,因为它带有“社区”和“社会凝聚力”的含义,而并非所有群体都具备这些特征。[19][20]

In 2010, the Journal of Global History published a special issue, “Zomia and Beyond”.[21] In this issue, contemporary historians and social scientists of Southeast Asia respond to Scott’s arguments. For example, although Southeast Asian expert Victor Lieberman[22] agrees that the highland people crafted their own social worlds in response to the political and natural environments that they encountered, he also finds Scott’s documentation to be very weak, especially its lack of Burmese-language sources, saying that not only does this undermine several of Scott’s key arguments, but it brings some of his other theories about Zomia into question.

【参考译文】2010年,《全球历史杂志》发表了一期特刊,名为“佐米亚及其以外”。[21]在这一期中,当代东南亚历史学家和社会科学家对斯科特的观点进行了回应。例如,尽管东南亚专家维克托·利伯曼(Victor Lieberman)[22]同意高地人民为了应对他们所遇到的政治和自然环境而创造了自己的社会世界,但他也认为斯科特的论据非常薄弱,尤其是缺乏缅甸语资料,并表示这不仅削弱了斯科特的几个关键论点,还使他对佐米亚的一些其他理论受到质疑。

Furthermore, Lieberman argues that Scott is overestimating the importance of manpower as a determinant in military success. While the bulk of Scott’s argument rests on the efforts of lowland states to dominate the highlands, Lieberman shows the importance of maritime commerce as an equally contributing factor.

【参考译文】此外,利伯曼认为斯科特高估了人力作为军事成功决定因素的重要性。虽然斯科特的主要论点建立在低地国家试图统治高地的基础上,但利伯曼指出了海上贸易作为同等重要因素的重要性。

Lieberman also says that examples not included in Scott’s analysis need to be taken into consideration. Scott firmly believes that the culture took shape as a defensive mechanism, as a reaction to surrounding political and social environments. Lieberman, however, argues that the highland peoples of Borneo/Kalimantan had virtually the same cultural characteristics as the Zomians, such as the proliferation of local languages and swidden cultivation, which were all developed without a lowland predatory state.[23]

【参考译文】利伯曼还表示,需要考虑斯科特分析中未包含的例子。斯科特坚信,这种文化是作为防御机制、作为对周围政治和社会环境的反应而形成的。然而,利伯曼认为,婆罗洲/加里曼丹的高地民族几乎具有与佐米亚人相同的文化特征,如当地语言的繁荣和刀耕火种的农业,而这些都是在没有低地掠夺性国家的情况下发展起来的。[23]

More recently, Scott’s claims have been questioned by Tom Brass.[24] Brass maintains that it is incorrect to characterize upland Southeast Asia as “state-repelling” “zones of refuge/asylum” to which people voluntarily migrate. This is, he argues, an idealization consistent with the “new” populist postmodernism, but not supported by ethnographic evidence. The latter suggests that populations neither choose to migrate to upland areas (but go because they are forced off valley land), nor – once there – are they beyond the reach of the lowland State. Consequently, they are anything but empowered and safe in such contexts.

【参考译文】最近,汤姆·布拉斯(Tom Brass)对斯科特的主张提出了质疑。[24]布拉斯认为,将东南亚高地描述为人们自愿迁移的“排斥国家的避难所/庇护区”是不正确的。他认为,这是一种与“新”民粹主义后现代主义相符的理想化说法,但民族志证据并不支持这一点。后者表明,人们既不是因为选择才迁移到高地地区(而是因为被迫离开河谷地带),也并不意味着——一旦到达高地——他们就能逃脱低地国家的控制。因此,在这样的背景下,他们远非强大和安全。

Edward Stringham and Caleb J. Miles analyzed historical and anthropological evidence from societies in Southeast Asia and concluded that they have avoided states for thousands of years. Stringham further analyzes the institutions used to avoid, repel and prevent would-be states. He further concludes that stateless societies like “Zomia” have successfully repelled states using location, specific production methods, and cultural resistance to states.[25]

【参考译文】爱德华·斯特林厄姆(Edward Stringham)和迦勒·J·迈尔斯(Caleb J. Miles)分析了东南亚社会的历史和人类学证据,并得出结论认为,这些社会数千年来一直在避免国家的形成。斯特林厄姆进一步分析了用来避免、排斥和阻止潜在国家的制度。他还得出结论认为,“佐米亚”这样的无国家社会成功地利用地理位置、特定的生产方式以及对国家的文化抵制来排斥国家。[25]

A. 参见(维基百科的相关词条)| See also

- Burma Road【滇缅公路】

- Hill tribe (Thailand)【山地部落(泰国)】

- Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area【大陆东南亚语言区】

- Mandala (political model)【曼陀罗(政治模式)】

- Monthon【行政区(泰国历史上的行政区划单位)】

B. 参考文献 | References

- ^ Michaud, Jean; Meenaxi B. Ruscheweyh; Margaret B. Swain, 2016. Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif. Second Edition. Lanham • Boulder • New York • London, Rowman & Littlefield, 594p.

- ^ Michaud J., 1997, “Economic transformation in a Hmong village of Thailand.” Human Organization 56(2) : 222-232.

- ^ Willem van Schendel, ‘Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance: jumping scale in Southeast Asia’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 20, 6, 2002, pp. 647–68.

- ^ James C. Scott, The art of not being governed: an anarchist history of upland Southeast Asia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

- ^ Michaud, J. 2010, Zomia and Beyond. Journal of Global History, 5(2): 205.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. Berkeley: U. of California Press, 1989.

- ^ Herman, Amid the Clouds and Mist. Robert D. Jenks, Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou. The Miao Rebellion, 1854-1873. Honolulu (HA), U. of Hawaii Press, 1994. Claudine Lombard-Salmon, Un exemple d’acculturation chinoise : la province du Guizhou au XVIIIe siècle. Paris, Publication de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, vol. LXXXIV, 1972 .

- ^ See Michaud J. , 2016 “Seeing the Forest for the Trees: Scale, Magnitude, and Range in the Southeast Asian Massif.” Pp. 1-40 in Michaud, Jean; Meenaxi B. Ruscheweyh; and Margaret B. Swain, Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the South-East Asian Massif. Second Edition. Lanham • Boulder • New York • London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ A.T. Rambo, ‘Development Trends In Vietnam’s Northern Mountain Region’, In D. Donovan, A.T.Rambo, J. Fox And Le Trong Cuc (Eds.) Development Trends In Vietnam’s Northern Mountainous Region. Hanoi: National Political Publishing House, pp.5-52, 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Lim, Territorial Power Domains. Andrew Walker, The Legend of the Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

- ^ “Willem van Schendel”. International Institute of Social History. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ Kratoska, P. H.; Raben, R.; Nordholt, H. S., eds. (2005). Locating Southeast Asia: Geographies of Knowledge and Politics of Space. Singapore University Press. p. v. ISBN 9971-69-288-0.

- ^ van Schendel, W. (2005). “Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance: Jumping scale in Southeast Asia”. In Kratoska, P. H.; Raben, R.; Nordholt, H. S. (eds.). Locating Southeast Asia: Geographies of Knowledge and Politics of Space. Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971-69-288-0.

- ^ Michaud 2010 Archived October 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michaud, J. (2009, February). “Handling Mountain Minorities in China, Burma, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos: From History to Current Concerns.” Asian Ethnicity 10: 25–49.

- ^ Scott, James C. (2009). The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale Agrarian Studies. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-300-15228-9.

Notes to pages 5 – 14: Other explicit proponents of a systematic view from the periphery include Michaud, Turbulent Times and Enduring Peoples, especially the Introduction by Michaud and John McKinnon, 1–25, and Hjorleifur Jonsson, Mien Relations: Mountain Peoples, Ethnography, and State Control (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005). F. K. L. Chit Hlaing [F. K. Lehman], “Some Remarks upon Ethnicity Theory and Southeast Asia, with Special Reference to the Kayah and Kachin,” in Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Burma, ed. Mikael Gravers (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2007), 107–22, esp. 109–10.

- ^ In addition, he maintains that many traits that are viewed in mainstream cultures as “primitive” or “backward” and used to denigrate hill peoples are actually adaptations to avoid state incorporation, such as lack of a written language, shifting messianic religious movements, or nomadism. Their presence is absent from most histories, since, as Scott puts it, “it is the peasants’ job to stay out of the archives.” Nonetheless, in reality he sees the relationship between upland and lowland peoples as reciprocal, since upland peoples are essential as a source of trade. Scott, James C. (2009). The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale Agrarian Studies. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-300-15228-9.

Notes to pages 5–14: Other explicit proponents of a systematic view from the periphery include Michaud, Turbulent Times and Enduring Peoples, especially the Introduction by Michaud and John McKinnon, 1–25; Turner, S., C. Bonnin and J. Michaud (2015) ‘Frontier Livelihoods. Hmong in the Sino-Vietnamese Borderlands’ (Seattle: University of Washington Press); and Hjorleifur Jonsson, Mien Relations: Mountain Peoples, Ethnography, and State Control (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005). F. K. L. Chit Hlaing [F. K. Lehman], “Some Remarks upon Ethnicity Theory and Southeast Asia, with Special Reference to the Kayah and Kachin,” in Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Burma, ed. Mikael Gravers (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2007), 107–22, esp. 109–10.

- ^ “Jean Michaud, Ph. D., Anthropologist”. Université Laval, Québec, Canada. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

Jean Michaud is a social anthropologist and specialises since 1988 on issues of social change among highland populations of Asia.

- ^ Michaud, Jean (April 2006). “Introduction”. Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif. Historical Dictionaries of Peoples and Cultures #4. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8108-5466-6. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

For this dictionary, a compromise solution has been adopted, which was to accept official national ethnonyms but correct mistakes whenever possible and cross-reference to alternative names. Close to 200 ethnonyms thus have their own entries, which is the largest number the relatively humble format of this series allows.

- ^ Michaud, Jean (2010). “Editorial – Zomia and beyond*”. Journal of Global History 5, London School of Economics and Political Science. 5 (2). Université Laval: 187–214. doi:10.1017/S1740022810000057.

This editorial develops two themes. First, it discusses how historical and anthropological approaches can relate to each other, in the field of the highland margins of Asia and beyond. Second, it explores how we might further our understandings of the uplands of Asia by applying different terms such as ‘Haute-Asie’, the ‘Southeast Asian Massif’, the ‘Hindu Kush–Himalayan region’, the ‘Himalayan Massif’, and in particular ‘Zomia’, a neologism gaining popularity with the publication of James C. Scott’s latest book….

- ^ Michaud, Jean (2010). “Journal of Global History”. Journal of Global History. 5 (2). Cambridge Journals Online. ISSN 1740-0228. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

Published for London School of Economics and Political Science

- ^ “Victor B. Lieberman”. Marvin B. Becker Collegiate Professor of Southeast Asia, pre-modern Burma, early modern world history. University of Michigan. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ Little, Daniel; Michael E. Smith; et al. (October 18, 2010). “Zomia reconsidered” (blogspot). web-based monograph. UnderstandingSociety. p. 1. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

[Lieberman’s] most recent volumes, Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800-1830 (v. 1) and Strange Parallels: Volume 2, Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800-1830, are directly relevant to Scott’s analysis.

- ^ Tom Brass (2012), “Scott’s ‘Zomia,’ or a Populist Post-modern History of Nowhere”, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 42:1, 123–33

- ^ Stringham, Edward (2012). “Repelling States: Evidence from Upland Southeast Asia”. Review of Austrian Economics. 25 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1007/s11138-010-0115-3. S2CID 144582680. SSRN 1715223.

C. 延伸阅读 | Further reading

- Drake Bennett (December 6, 2009). “The Mystery of Zomia”. Ideas. Globe Newspaper Company. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

In the lawless mountain realms of Asia, a Yale professor finds a case against civilization

- Bunopas, Sangad; Vella, Paul (November 17–24, 1992). Geotectonics and Geologic Evolution of Thailand (PDF). National Conference on Geologic Resources of Thailand: Potential for Future Development. Department of Mineral Resources, Bangkok. pp. 209–229. ISBN 9789747984415. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 20, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

Thailand consists of Shan–Thai and Indochina microcontinents or terranes welded together by the subsequently deformed Nan Suture…. During the Middle Triassic Shan–Thai sutured nearly simultaneously to Indochina and to South China, the continent–continent collision being a part of the Indosinian Orogeny and Indochina tended to underthrust Shan–Thai.

分享到: