中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。

关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及根据名称精确检索已搬运的词条,请点击这里访问辽观网站。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

目录

0. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

羌族,是古羌人的后裔之一,自称尔玛、日麦、弥。羌是一种称呼,羌族称之为‘羊部落’,源于其以羊为标志(图腾)[1],是中国西部的一个少数民族,总人口30万。

They live mainly in a mountainous region in the northwestern part of Sichuan (Szechwan) on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau.[2]

【参考译文】他们主要居住在四川(川)西北部的一个山区,位于青藏高原的东缘。[2]

松潘羌族有自称‘羌合基’,羊部落。

藏族称‘播合基’,牛部落。

有口语,文字失落。羌族至今仍保留自己独特的民族传统、生活文化与巫觋宗教,信奉天神“阿爸”,也兼信别神,信奉天神、地神、山神、山神娘娘和树神、白石、神塔等多神崇拜,使用马、猴、羊等图腾。其语言属于汉藏语系藏缅语族羌语支。

The modern Qiang refer to themselves as Rma (/ɹmæː/ or /ɹmɛː/, 尔玛, erma in Chinese or RRmea in Qiang orthography) or a dialect variant of this word. However, they did not define themselves with the Chinese term “Qiang ethnicity” (Chinese: 羌族) until 1950, when they were officially designated Qiāngzú.[3]

【参考译文】现代羌族人称自己为尔玛(/ɹmæː/ 或 /ɹmɛː/,或羌文正字法中的RRmea)。然而,直到1950年他们被正式指定为羌族(汉语:羌族)之前,他们并没有用汉语术语“羌族”来定义自己。[3]

Qiang has been a term that has historically referred less to a specific community, but more to the fluid western boundary of Han Chinese settlers. Chinese philosophers of the Warring States period also mentioned a ‘Di-Qiang‘ peoples living on the western edge of Han territory. They were known for their customs of cremation.[4]

【参考译文】羌这个词在历史上更多地不是指一个特定的社区,而是指汉族定居者的流动的西部边界。战国时期的中国哲学家也提到了居住在汉族领土西边缘的“氐羌”民族。他们以火葬的习俗而闻名。[4]

1. 历史 | History

更多信息:古羌人 / See also: Qiang (historical people)

1.1 羌族与古羌人

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

“羌人”分为“先古羌”(秦朝之前的古羌人)和“后古羌”(秦朝之后的西羌“胡夷”民族又叫羌族),先古羌在秦统一后,和东部人群融为一体,形成汉族的胚胎[2]。有学者认为:包括夏、周、秦等国家,可能都与古羌人相关。殷商时有用羌人来祭神的习俗,被认为来自于战争俘虏,是频繁接触、摩擦的象征。

People called “Qiang” have been mentioned in ancient Chinese texts since they first appeared in oracle bone inscriptions 3,000 years ago. Recognized as a ‘first ancestor culture’, there is evidence of the Qiang in northwestern China dating back to the 16th-11th centuries B.C., when they were recorded bringing tribute to the Shang Dynasty.[5][6] They were primarily known to practice pastoral nomadism, and resisted westward expansion of the Han Empire, gradually shifting to the south-west of their ancestral lands.

【参考译文】被称为“羌”的人最早出现在3000年前的甲骨文记载中,自古以来的中国文献中就有关于他们的记载。作为“始祖文化”,有证据表明羌族在公元前16世纪至公元前11世纪的中国西北部地区活动,当时他们被记录为向商朝进贡。[5][6]他们主要以游牧为生,抵制汉朝向西的扩张,逐渐从他们的祖居地向西南迁移。

However, the name Qiang has been applied to a variety of groups that might not be the same as the modern Qiang. Many of the people formerly designated as “Qiang” were gradually removed from this category in Chinese texts as they become sinicised or reclassified. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the term “Qiang” denoted only non-Han people living in the upper Min River Valley and Beichuan area, the area now occupied by the modern Qiang.[7] Nonetheless, most modern scholarship assumes that modern Qiang are descended from the historical Qiang people.[8]

【参考译文】然而,“羌”这个名字曾被应用于各种可能并不等同于现代羌族的群体。许多曾被指定为“羌”的人,随着他们逐渐汉化或被重新分类,在中国文献中逐渐被从这个类别中移除。到了明朝和清朝,术语“羌”仅指生活在岷江上游河谷和北川地区的非汉族人民,这个地区现在被现代羌族占据。[7]尽管如此,大多数现代学术研究认为,现代羌族是历史羌族人的后裔。[8]

During the wars centering on the 1580s, the term “Qiang” or less often “Qiang Fan” was increasingly applied to areas in the southern sections of the Upper Min valley that are identified as Qiang today; and in the same materials the term “Fan” was used for areas to the north and east that are today Zang (Tibetan). The ruins reported by Western travellers in the early 20th century testify to the violence of that official repression. We suggest that the origins of the modern Qiang, who for the past four centuries have cast their lot with Chinese rulers more readily than the people of Shar khog, may be sought in the Ming, beginning with Chinese in-migration at Maozhou in the 15th century and culminating in the violence upriver in the 1580s.[9]

— Xiaofei Kang, Donald S. Sutton

【参考译文】在围绕1580年代的战争中,术语“羌”或较少使用的“羌番”越来越多地被应用于今天被识别为羌族的岷江上游南部地区;在同一史料中,“番”这个词被用于指代今天属于藏族(藏)的北部和东部地区。20世纪初西方旅行者报告的废墟证明了那次官方镇压的暴力。我们建议,现代羌族的起源,他们过去四个世纪比Shar khog地区的人民更愿意与中国统治者结盟,可能要追溯到明朝,从15世纪开始在茂州的中国内地移民开始,并在1580年代的上游暴力事件中达到高潮。[9]

——康晓菲,唐纳德·S·萨顿

Analysis of Han and Western (European) scholarly sources reveals that in the first half of the twentieth century, there was no coherent ‘Qiang’ culture in the Upper Min Valley of northwestern Sichuan. Rather, there existed a plethora of inhabited regions with settlers of individual communities identifying themselves as rma. A significant cultural variation was observed even among neighboring communities. In particular, Han and Tibetan influences were prevalent in those rural communities.[4]

【参考译文】分析汉文和西方(欧洲)学术资源显示,在二十世纪上半叶,四川西北部岷江上游地区并不存在一个统一的“羌”文化。相反,那里存在着众多居住区域,各社区定居者自称为rma。即使是相邻的社区之间,也观察到了显著的文化差异。特别是,汉族和藏族的影响在这些农村社区中普遍存在。[4]

后古羌自秦朝以后从西北涌入,发展演变成为今天的部分汉族、羌族以及西南各操藏缅语族语言的少数民族,包括:藏族、彝族、白族、纳西族、普米族、傈僳族、拉祜族、基诺族、阿昌族、景颇族、独龙族、怒族、土家族等。[3]

今天的所称的“羌族”,仅仅是古西羌诸部中的一支。今天的羌族以及古西羌诸后裔民族都经历了多次迁徙。今天的这支古西羌部落“羌族”在进入今天居住的岷江、涪江流域一带之前,自称“子拉族”[4]。“羌戈大战”后自称“尔玛人”。

When Qiang was officially designated an ethnic group in 1950, they numbered only 35,600. Many sought to gain Qiang status due to government policy of prohibition of discrimination as well as economic subsidies for minority nationalities.[7] As a result, the Qiang population has increased due to the reclassification of people.[10] From 1982 to 1990, 75,600 Han people changed their ethnicity to Qiang, and from 1990 to 2000, 96,500 Han people became Qiang. Another 49,200 people reclaimed their Qiang ethnicity from 1982 to 1989. In total, some 200,000 Han people became Qiang. As a result, there were 300,000 Qiang people in 2010, 200,000 of which lived in Sichuan, predominantly in the Ngawa Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, Beichuan Qiang Autonomous County and in the counties of Mao, Wenchuan, Li, Heishui, and Songpan.[11]

【参考译文】1950年,羌族被正式定为一个民族时,他们的人口数量仅为35,600人。由于政府禁止歧视的政策以及对少数民族的经济补贴,许多人寻求获得羌族身份。[7]因此,由于人们的重新分类,羌族人口有所增加。[10]从1982年到1990年,有75,600名汉族人改变了他们的民族成分成为羌族,从1990年到2000年,又有96,500名汉族人成为羌族。另外,从1982年到1989年,有49,200人恢复了他们的羌族身份。总的来说,大约有20万汉族人成为了羌族。因此,到2010年,羌族人口达到了30万人,其中20万人居住在四川,主要分布在阿坝藏族羌族自治州、北川羌族自治县以及茂县、汶川、理县、黑水和松潘等县。[11]

1.2 2008年四川地震 | 2008 Sichuan earthquake

On 12 May 2008, the Qiang people were heavily affected by the 8.0 magnitude 2008 Sichuan earthquake. With 69,142 total deaths, and 17,551 missing,[12] over 30,000 of the people killed were ethnic Qiang (10 percent of the total Qiang population).[13][14] Major restoration efforts were made in the A’er village, one of the few remaining centers of Qiang culture, by the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center (CHP).[6] Specifically, preservation of the Qiang languages (which have no written form) was of concern, and several recording repositories were made to preserve the tales remembered only by the shibi or duangongs restoration attempts were made in consideration of the 1989 UNESCO Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore, and ensured maximum participation of the local inhabitants, the custodians of the culture that was being preserved. The A’er stone tower, of particular significance, was carefully restored in 2012 by the A’er villagers themselves using authentic materials and techniques.[6]

【参考译文】2008年5月12日,羌族人民遭受了8.0级2008年四川地震的严重影响。地震造成69,142人死亡,17,551人失踪。[12]在遇难者中,超过30,000人是羌族(占总羌族人口的10%)。[13][14]北京文化遗产保护中心(CHP)在阿儿村进行了重大修复工作,阿儿村是少数几个仍保留羌文化的中心之一。[6]特别是,由于羌语(没有书面形式)的保护成为关注焦点,因此建立了几个录音资料库来保存只有释比或端公记得的故事。修复工作考虑到了1989年联合国教科文组织关于保护传统文化和民俗的建议,并确保了当地居民,即所保存文化的守护者,最大程度的参与。具有特殊意义的阿儿石塔,在2012年由阿儿村村民自己使用正宗材料和工艺精心修复。[6]

2. 语言 | Languages

The Qiang speak the agglutinative Qiangic languages,[15] a subfamily of the Tibeto-Burman languages.[16] However, Qiang dialects are so different that communication between different Qiang groups is often in Mandarin. There are numerous Qiang dialects; traditionally they are split into two groups, Northern Qiang and Southern Qiang, although in fact the Qiang language complex is made up of a large number of dialectal continua which cannot be easily grouped into Northern or Southern. The education system largely uses Standard Chinese as a medium of instruction for the Qiang people, and as a result of the universal access to schooling and TV, very few Qiang cannot speak Chinese but many Qiang cannot speak Qiangic languages.[17]

【参考译文】羌族人说的是黏着语系的羌语,[15]这是藏缅语系的一个分支。[16]然而,羌语方言之间的差异如此之大,以至于不同羌族群体之间的交流通常使用普通话。羌语方言众多;传统上它们被分为两组,北部羌语和南部羌语,尽管实际上羌语语言复合体由大量无法轻易归入北部或南部的方言连续体组成。教育系统在很大程度上使用标准汉语作为羌族人的教学媒介,由于普遍接受学校和电视的影响,很少有羌族人不会说汉语,但许多羌族人不会说羌语。[17]

Until recently, there was no script for the Qiang language, and the Qiang used a system of carving marks on wood to represent events or communicate.[18] In the late 1980s a writing system was developed for the Qiang language based on the Qugu (曲谷) variety of a Northern dialect using the Latin alphabet.[16] The introduction has not been successful due to the complexities of the Qiang sound system and the concomitant difficulty of its writing system, as well as the diversity of the Qiang dialects and the lack of reading material.[16] The Qiang also use Chinese characters.[citation needed] More recently, a unique script has been developed specifically for Qiang, known as the Qiang or Rma script.

【参考译文】直到最近,羌语还没有书写系统,羌族人使用一种在木头上刻记号的方式来代表事件或进行交流。[18]在20世纪80年代末,基于北部方言的曲谷(Qugu)变体,为羌语开发了一种使用拉丁字母的书写系统。[16]由于羌语声音系统的复杂性及其书写系统的相应难度,以及羌语方言的多样性以及阅读材料的缺乏,这种书写系统的引入并不成功。[16]羌族人还使用汉字。[需要引用]更近一段时间,为羌族专门开发了一种独特的文字,称为羌文或尔玛文。

3. 文化和宗教 | Culture and religion

3.1 宗教信仰

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

As a result of their geographic location on the periphery of Tibetan and Han majorities Qiang culture is a unique amalgamation of their own religions and Han, Tibetan, Muslim, and Christian influences.[5] This attests to the significant intra-diversity of the Qiang people, a phenomenon caused almost exclusively by the linguistic barriers and topographical difficulty of the regions they inhabit.

【参考译文】由于羌族位于藏族和汉族主体民族的边缘地区,羌族文化是其自身宗教与汉、藏、穆斯林和基督教影响的独特融合。[5]这证明了羌人民内部显著的多样性,这种现象几乎完全是由他们所居住地区的语言障碍和地形困难所引起的。

The majority of the Qiang adhere to a pantheistic religion involving guardian mountain deities.[5][4] Several nearby villages may share a higher-level mountain deity out of proximity. These deities served not just as religious idols, but practical protections of resource rights and territorial boundaries in a region of severe resource competition.

【参考译文】大多数羌族人信仰一种涉及守护山神的泛神论宗教。[5][4]几个邻近的村庄可能因为地理位置相近而共享一个更高层次的山神。这些神灵不仅仅是宗教偶像,而且在资源竞争激烈的地区,它们还充当着资源权利和领土界限的实际保护者。

信仰与图腾:

- “羊”文化:羌族从信仰和生活都和羊密切相关,民族标记就是“羊”。羌族祭祀天神用羊、吉祥物是羊;生活上吃、穿、用的都离不开羊。 “白石”文化:羌族对白石情有独钟,认为“神圣而吉祥”。原因之一是对白色的传统崇拜;之二是历史上白石曾经帮助他们打败了敌人而能够在今天的居所(四川岷江、涪江流域)结束长途迁徙和逼迫,终于安顿下来。

- 释比文化:羌族的民族宗教信仰中,作为祖传的神职人员被称为“释比”(音:Rebbi)[来源请求],他们是羌族中的宗教领袖、祭司,也是巫师,担当神和人、人和鬼之间的中介人。他们是羌族中最权威的文化传承者和知识集大成者。释比做法事的职份,一般有如下两种情况:祭司(祭天神、治病、驱鬼、祈福等)、巫师(拜龙和诸地神、打卦占卜、经火等巫术)。在2008年“5.12”大地震后,释比已所剩无几。

Generally, there is a spectrum spanning from the Eastern edge of the historical Tibetan Kingdoms to the Han Empire – those who live nearer to the Tibetans (northwest) exhibit more elements of Tibetan Buddhism, while Han Chinese culture prevails among those living in the south and east.[4] Due to this, the mountain deities worshiped as village guardians became part of the lowest level of the western Tibetan Buddhist pantheon, while Taoism and Chinese Buddhism temples encroached upon the culture to the east. In eastern temples, mountain deities have disappeared entirely, with religious practice practically indistinguishable from the Han Chinese.

【参考译文】通常,存在一个从历史上藏族王国东部边缘到汉族帝国的谱系——那些生活在靠近藏族(西北部)的人展示了更多藏族佛教的元素,而汉族文化在南部和东部居住的人中占主导地位。[4]因此,作为村庄守护神而被崇拜的山神成为了西部藏族佛教万神殿中最低层次的一部分,而道教和汉传佛教寺庙的文化影响向东蔓延。在东部寺庙中,山神已经完全消失,宗教实践实际上与汉族中国人无法区分。

In regards to their local religions, the Qiang practice a form of animism, worshiping nature gods and ancestral spirits, and specific white stones (often placed atop watchtowers) are worshiped as representatives of gods. Villages worship five great deities and twelve lesser ones, though the pantheon consists of gods of equal importance dedicated to almost every social function. However, there is considered to be one supreme Abamubita (God of Heaven).[19]

【参考译文】关于他们的地方宗教,羌族实践一种形式的万物有灵论,崇拜自然神和祖先灵魂,特定的白石(通常放置在瞭望塔顶部)被作为神的代表来崇拜。各村寨崇拜五位大神和十二位较小的神,尽管万神殿由几乎每一个社会功能都有的同等重要的神组成。然而,被认为存在一个至高无上的阿坝姆比塔(天神)。[19]

3.2 端公

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

In Qiang villages, the culture is remembered and practice primarily by the duangong, known as bi in the Qiang language. As keepers of the culture, these village shamans hold great importance in the preservation of Qiang heritage. Though there is no gender limitation, no female duangongs exist currently.[5] They are also keepers of the two most important symbols of Qiang religion, known as the duangong’s tools: the sheepskin drum and a preserved a monkey skull, known as the AbaMullah.[5]

【参考译文】在羌族村寨中,文化主要通过被称为“端公”的人来记忆和实践,羌语中称之为“比”。作为文化的守护者,这些村庄的巫师在保存羌族遗产方面具有极其重要的地位。尽管没有性别限制,但目前没有女性端公存在。[5]他们还是羌族宗教两个最重要的象征的守护者,被称为端公的工具:羊皮鼓和一种被称为阿坝穆拉的保存完好的猴子头骨。[5]

Duangongs function as priests, scholars, medicine men and village elders all rolled into one. Though they live ordinary everyday lives, serving regular social functions as part of the village community, their possession of the duangong tools demarcates their explicit importance to the village’s spiritual culture. Almost all ceremonies, ranging from funerals to healing rituals are performed by the duangong. They are believed to have mysterious powers which allow them to be in constant communication with the world of spirits and ghosts, and thus straddle the line between healer and wizard. Important to note, however, is that the duangong does not earn his living from his status, but as a worker of whatever trade he chooses.[5] Another key difference between duangongs in Qiang culture and the idea of the ‘shaman’ is that while shamans are ‘chosen by the gods’, anyone can become a duangong given the appropriate training.

【参考译文】端公集牧师、学者、药师和村中长者的角色于一身。尽管他们过着普通的日常生活,作为村庄社区的一部分履行常规的社会功能,但他们拥有端公工具,这标志着他们对村庄精神文化的重要性。几乎所有的仪式,从葬礼到治疗仪式,都是由端公来执行的。人们相信他们拥有神秘的力量,可以与灵界和鬼魂世界保持不断的沟通,因此他们在治疗师和巫师之间游走。然而,值得注意的是,端公并不是靠他的地位谋生,而是作为他选择的任何行业的劳动者。[5]羌族文化中的端公与“巫师”概念之间的另一个关键区别在于,虽然巫师是“被神选中的”,但任何经过适当训练的人都可以成为端公。

To become a duangong, one must pass the gaigua, an initiation/graduation ceremony where the individual is confirmed in their position by the village and receives their own set of duangong tools; the monkey skin hat, sheepskin drum, holy stick, and AbaMullah, often handed down over fifteen generations. However, the turbulences of China’s Cultural Revolution led to the disappearance of many tools, with no shaman currently in possession of a full set. These disappearances are primarily attributed to confiscation by Chinese government search teams in pursuit of Chinese national modernization. However, several tools are postulated to have been hidden away by villagers in an attempt to preserve Qiang possession of their historical artifacts.[5]

【参考译文】要成为端公,一个人必须通过盖卦仪式,这是一个启蒙/毕业仪式,个人通过村庄的确认来确立他们的地位,并接收自己的一套端公工具;包括猴皮帽、羊皮鼓、神棍和阿坝穆拉,这些工具通常要传承十五代。然而,中国文化大革命的动荡导致了许多工具的消失,目前没有巫师拥有完整的一套。这些消失主要归因于中国政府搜查队在追求国家现代化的过程中进行的没收。然而,据推测,一些工具被村民们隐藏起来,试图保留羌族对其历史文物的拥有。[5]

For most Qiang villages, consecrated white stones, believed to be imbued with powers of the gods through certain rituals, are placed on the top of towers as a good luck symbols. These squared stone towers are traditionally located on the edge of Qiang villages and on the top of nearby hills as well.[6]

【参考译文】对于大多数羌族村寨来说,通过某些仪式被认为被神力附身的神圣白石被放置在塔顶作为吉祥的象征。这些方形的石塔传统上位于羌族村寨的边缘以及附近山丘的顶部。[6]

4. 生活方式 | Lifestyle

The Qiang today are mountain dwellers. A fortress village, zhai 寨, composed of 30 to 100 households, in general, is the basic social unit beyond the household. An average of two to five fortress villages in a small valley along a mountain stream, known in local Chinese as gou 沟, make up a village cluster (cun 村). The inhabitants of fortress village or village cluster have close contact in social life. In these small valleys, people cultivate narrow fluvial plains along creeks or mountain terraces, hunt animals or collect mushrooms and herbs (for food or medicine) in the neighboring woods, and herd yaks and horses on the mountain-top pastures.[6]

【参考译文】今天的羌族人是山地居民。一般来说,由30到100户家庭组成的堡垒式村庄,即寨,是超越家庭的基本社会单位。沿着山溪的小山谷,当地汉语称为沟,通常由两到五个堡垒村庄组成一个村庄集群(村)。堡垒村庄或村庄集群的居民在社会生活中有着密切的联系。在这些小山谷中,人们沿着小溪或山地梯田耕种狭窄的河流平原,在邻近的树林中狩猎动物或采集蘑菇和草药(用于食用或药用),并在山顶牧场放牧牦牛和马匹。[6]

In terms of subsistence and diet, northwestern displayed greater reliance on animal husbandry than agriculture, thus consuming more dairy and meat products. Meanwhile, southeastern settlers favor agricultural practices, resulting in greater consumption of grains and wheat.[4] This northwest to southwest gradient is observable in many aspects of Qiang culture due to their geographic location between two distinct (relative) majority cultures.

【参考译文】在生计和饮食方面,西北部的羌族表现出对畜牧业的更大依赖,而不是农业,因此他们消费更多的乳制品和肉类产品。与此同时,东南部的定居者更倾向于农业实践,导致他们更多地消费谷物和小麦。[4]由于羌族地理位置介于两个截然不同的(相对)多数文化之间,这种从西北到西南的梯度在羌文化的许多方面都显而易见。

The Qiang constructed watchtowers and houses with thick stone walls and small windows and doors.[3] Each village may have had one or more stone towers in the past, and these Himalayan Towers still survive in some Qiang villages and remain a distinctive feature in these villages.[20] Though Qiang villages historically served as fortified settlements with several defense mechanisms, these functions were lost over time. The Communist government’s 1949 establishment saw the removal of defense installations as part of a national unity policy.[6] Villagers live in granite stone houses generally consisting of two to three stories. The first floor is meant for keeping livestock and poultry, while the second floor is meant for the living quarters, and the third floor for grain storage. If the third floor does not exist, the grains will be kept on the first or second floor instead.[6]

【参考译文】羌族建造了带有厚石墙和小窗户、门的瞭望塔和房屋。[3]过去每个村庄可能都有一座或多座石塔,这些喜马拉雅塔楼在某些羌族村庄中仍然保存下来,并成为这些村庄的一个独特特征。[20]虽然历史上的羌族村庄曾作为带有多种防御机制的设防定居点,但这些功能随着时间的推移而丧失。1949年共产党政府成立后,作为国家统一政策的一部分,拆除了一些防御设施。[6]村民们通常居住在由两到三层组成的花岗岩石头房子里。一楼用于饲养家畜和家禽,二楼用于居住,三楼用于储存粮食。如果不存在第三层,粮食将保存在第一层或第二层。[6]

Sheep are considered particularly sacred in Qiang culture, as they are the source of much of a village’s livelihood. As such, wool is the primary material of which clothing is made. Both the menfolk and womenfolk wear gowns made of gunny cloth, cotton, and silk with sleeveless wool jackets. White is particularly sacred as a color among the Qiang.[4] Due to the harsh climate of their lands, the Qiang have developed clothing to adapt to it. A common dress is the “Yangpi Gua” (a kind of sleeveless jacket made of sheepskin or goatskin), and bind puttees to protect against the cold weather. Additionally, they are known to wear the “Tou Pa” (cloth head coverings) around head, waistband, tie an apron around one’s waist, and wear “Yunyun Shoe” (a sharp-pointed and embroidered shoes with typical Qiang characteristics). The dress, especially, women’s dress, is trimmed with lace and their collars are decorated with silver ornaments.[21]

【参考译文】在羌族文化中,羊被视为尤其神圣,因为它们是村庄生计的主要来源。因此,羊毛是制作衣服的主要材料。羌族的男性和女性都穿着由粗布、棉布和丝绸制成的大衣,并搭配无袖的羊毛夹克。白色在羌族中尤其被视为神圣的颜色。[4]由于他们土地上的恶劣气候,羌族发展出了适应这种气候的服装。一种常见的服饰是“羊皮挂”(一种由羊皮或山羊皮制成的无袖夹克),并且绑上裹腿以抵御寒冷天气。此外,他们还习惯在头部、腰部缠绕“头帕”(布制头饰),在腰间系上围裙,并穿着“云云鞋”(一种具有典型羌族特征的尖头刺绣鞋)。尤其是女性的服饰,边缘饰有蕾丝,领口装饰有银饰。[21]

Millet, highland barley, potatoes, winter wheat, and buckwheat serve as the staple food of the Qiang. Consumption of wine and smoking of orchid leaves are also popular among the Qiang.

【参考译文】羌族的主食包括小米、高原大麦、土豆、冬小麦和荞麦。饮用葡萄酒和吸食兰花叶在羌族中也很流行。

Skilled in construction of roads and bamboo bridges, the Qiang can build them on the rockiest cliffs and swiftest rivers. Using only wooden boards and piers, these bridges can stretch up to 100 meters. Others who are excellent masons are good at digging wells. Especially during poor farming seasons, they will visit neighboring places to do chiseling and digging.

【参考译文】羌族擅长修建道路和竹桥,他们能够在最险峻的悬崖和最湍急的河流上建造。仅使用木板和桥墩,这些桥梁可以延伸至100米。其他擅长石工的羌族人擅长挖井。特别是在农业收成不好的季节,他们会去邻近的地方进行錾刻和挖掘。

Embroidery and drawn work are done extemporaneously without any designs. Traditional songs related to topics such as wine and the mountains are accompanied by dances and the music of traditional instruments such as leather drums.

【参考译文】刺绣和绘图工作是即兴创作的,没有任何设计图样。与酒和山脉等主题相关的传统歌曲,伴随着舞蹈和传统乐器如皮鼓的音乐。

羌族的传统服饰为男女皆穿细麻布长衫、崇尚蓝色、羊皮坎肩,包头帕,束腰带,裹绑腿。羌族妇女挑花刺绣久负盛名。

传统的天然垒石房、高碉、城墙:修建高碉是羌族的特有的传统技艺,也通常是天然石垒砌而成,却十分坚固。羌族的城墙也颇有特色。

佩刀、陶罐与酒文化:制作特色的陶罐,特别是有波纹的双耳罐,是羌族特别是“笮”羌的特长。中华人民共和国成立前,羌族男人几乎人人有佩刀。这和他们多战事有关,也和生活上方便使用有关,比如割肉、砍柴等。“咂酒”是用青稞或麦子做的粮食酒,集体饮用;“醉酒”是羌族的一大特色。羌族不论男女,以“醉”为豪气,常常在聚会时候酩酊大醉。

民族舞蹈:全民同乐之圈舞萨朗舞,与藏族锅庄同。不论男女老幼,羌族都喜欢在一起跳圈圈舞蹈。这种舞蹈围成一圈,表示全村民同心合一敬神、集体和睦同欢之意。羌族文化讲究“阴阳”,有时跳舞会把男女分在圈圈两边。有时会一男一女配搭牵手跳舞。

特别讲礼仪的婚俗:多礼节、蒙盖头。其传说蒙盖头是自羌人传给汉人。

羊皮鼓舞:祭祀天神的舞蹈,以击羊皮与天神沟通。羌语称羊皮鼓“米日木”或“日木”。

春季节:又叫“祭山会”,每年五、六月间谷物初熟季节举行歌舞宴会,杀羊祭天、求神祈福。

秋季节:又叫“羌历年”,每年十、十一月间庄稼收成季节举行歌舞盛会,杀羊谢天、感恩求福。

羌绣

羌红:挂于门框、羊头上以及人身上的吉祥绸带。

羌笛:“羌笛何须怨杨柳,春风不渡玉门关。”

羌族文化在2008年汶川大地震中受严重破坏,亟待抢救,据报道,目前正在论证建立“羌族文化生态保护实验区”的方案。

2024年羌族的“羌年”从急需保护的非物质文化遗产名录转入人类非物质文化遗产代表作名录[7]。

5. 遗传起源 | Genetic origin

Genetic evidence reveals a predominantly Northern Asian-specific component in Qiangic populations, especially in maternal lineages. The Qiangic populations are an admixture of the northward migrations of East Asian initial settlers with Y chromosome haplogroup D (D1-M15 and the later originated D3a-P47) in the late Paleolithic age, and the southward Di-Qiang people with dominant haplogroup O3a2c1*-M134 and O3a2c1a-M117 in the Neolithic Age.[22]

【参考译文】遗传证据揭示了羌族人群中存在主要的北亚特定成分,尤其是在母系血统中。羌族人群是东亚最初定居者向北迁移的混合群体,这些定居者在旧石器时代晚期携带Y染色体单倍群D(D1-M15和后来起源的D3a-P47),以及在新石器时代携带主导单倍群O3a2c1*-M134和O3a2c1a-M117的南下氐羌人群的混合。

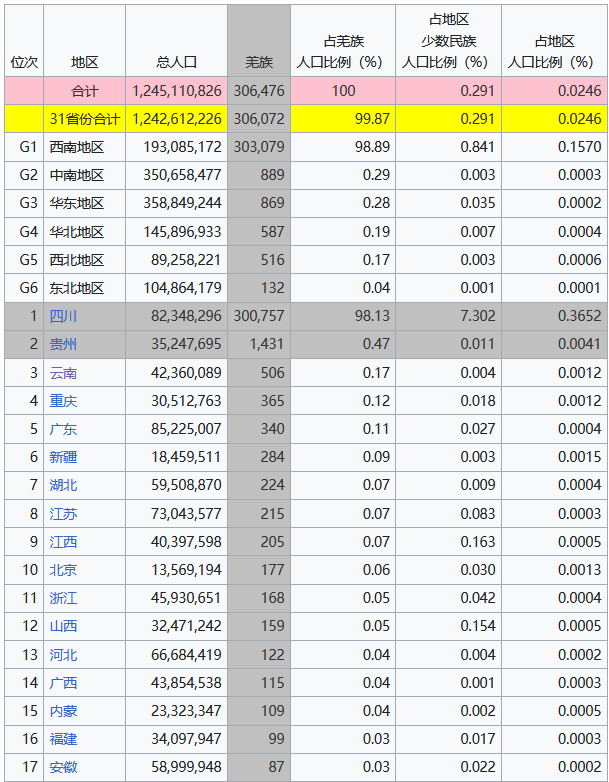

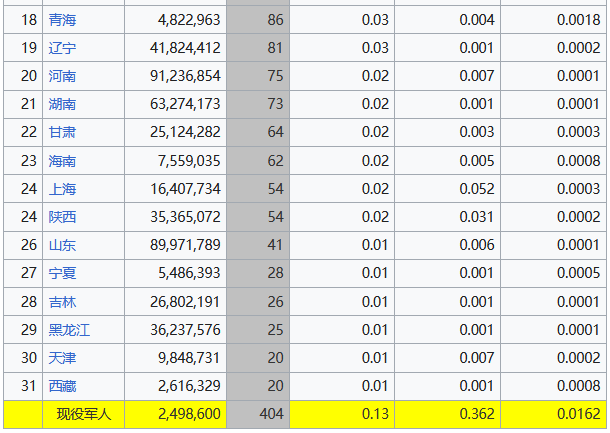

6. 羌族人口分布

中国2000年第五次人口普查各地羌族人口列表(普查时点人口,单位:人)[6]

7. 居住位置及民族自治地方

A. 参见(维基百科的相关词条)| See also

- Northern Qiang language【北部羌语】

- Southern Qiang language【南部羌语】

B. 研究书目

- 王明珂:《游牧者的抉择:面对汉帝国的北亚游牧部族》(桂林:广西师范大学出版社,2008)。

- 王明珂:《羌在汉藏之间:川西羌族的历史人类学研究》 (北京:中华书局,2008)。

- 黎明钊:《悬泉置汉简的羌人问题——以〈归义羌人名籍〉为中心[永久失效链接]》。

- 王明珂:《青稞、荞麦与玉米——一个对羌族“物质文化”的文本与表征分析 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)》。

- 王明珂:《民族考察、民族化与近代羌族社会文化变迁 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)》。

- 马长寿:《氐与羌》(上海:上海人民出版社,1984)。

C. 英文词条参考文献 | References

C1. 引用列表(与文中标号对应)| Citations

- ^ “中华人民共和国国家统计局 >> 第五次人口普查数据”. www.stats.gov.cn. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ LaPolla & Huang (2003), p. 1.

- ^ LaPolla & Huang (2003), p. 6.

- ^ Wang, Ming-KE (2002). “Searching for Qiang Culture in the First Half of the Twentieth Century”. Inner Asia. 4 (1): 131–148. doi:10.1163/146481702793647588. ISSN 1464-8172.

- ^ Zevik, Emma (January 2002). “First Look: The Qiang People of Sichuan”. Asian Anthropology. 1 (1): 195–206. doi:10.1080/1683478X.2002.10552525. ISSN 1683-478X.

- ^ Yunxia, Wang; Prott, Lyndel V. (2016-01-02). “Cultural revitalisation after catastrophe: the Qiang culture in A’er”. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 22 (1): 26–42. doi:10.1080/13527258.2015.1074933. ISSN 1352-7258.

- ^ Wang Ming-ke. “From the Qiang Barbarians to the Qiang Nationality: The Making of a New Chinese Boundary”.

- ^ Wen 2014, p. 70.

- ^ Kang & Sutton 2016, p. 64.

- ^ “Qiang, Cimulin” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007.

- ^ Wen 2014, p. 70-72.

- ^ Han, Li; Berry, John W.; Zheng, Yong (2016-10-14). “The Relationship of Acculturation Strategies to Resilience: The Moderating Impact of Social Support among Qiang Ethnicity following the 2008 Chinese Earthquake”. PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0164484. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1164484H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164484. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5065190. PMID 27741274.

- ^ Mark Magnier and Barbara Demick (May 21, 2008). “Quake threatens a culture’s future”. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Dooley, Ben (11 May 2018). “Nearly wiped out by quake, China’s Qiang minority lives on”. AFP – via France 24.

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 2010. p. 970. ISBN 9780080877754.

- ^ LaPolla & Huang (2003), pp. 2–3.

- ^ LaPolla & Huang (2003), p. 5.

- ^ LaPolla & Huang (2003), pp. 3.

- ^ “Mountain gods – Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia”. tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2024-04-16.

- ^ Daniel McCrohan (19 August 2010). “The inside info on China’s ancient watchtowers”. Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013.

- ^ Li, Jia; Fan, Weijue (August 2016). “Effect Factor Analysis of the Change in Traditional Raiment Culture of the Qiang Nationality”. Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Humanity, Education and Social Science. Atlantis Press. pp. 580–584. doi:10.2991/ichess-16.2016.124. ISBN 978-94-6252-206-0.

- ^ Chuan-Chao Wang; Ling-Xiang Wang; Rukesh Shrestha; Manfei Zhang; Xiu-Yuan Huang; Kang Hu; Li Jin; Hui Li (2014). “Genetic Structure of Qiangic Populations Residing in the Western Sichuan Corridor”. PLOS ONE. 9 (8). e103772. Bibcode:2014PLoSO…9j3772W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103772. PMC 4121179. PMID 25090432.

C2. 来源文献 | Sources

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). “Chapter 9: War With Qiang, 62 BCE”. Wars With the Xiongnu: A Translation from Zizhi Tongjian. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4.

- LaPolla, Randy J.; Huang, Chenglong (2003). A Grammar of Qiang: With Annotated Texts and Glossary. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110178296.

- Kang, Xiaofei; Sutton, Donald S. (2016). Contesting the Yellow Dragon: Ethnicity, Religion, and the State in the Sino-Tibetan Borderland. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31923-3.

- Wen, Maotao (2014). The Creation of the Qiang Ethnicity, its Relation to the Rme People and the Preservation of Rme Language (Master thesis). Duke University.

D. 中文词条参考文献

- ^ 东汉《说文解字》:“羌,西戎牧羊人也。”东汉《风俗通义》:“羌,本西戎卑贱者也,主牧羊。故‘羌’从羊、人,因以为号。”

- ^ 翦伯赞《先秦史》

- ^ 国家民委《羌族简史》

- ^ 庄学本《十年西行记》

- ^ 西羌是隶属于西戎的别支,从事牧羊,《说文》称:“羌,西戎牧羊人也。从人从羊,羊亦声”;《风俗通义》也说:“羌,本西戎卑贱者也,主牧羊。故‘羌’从羊、人,因以为号。”

- ^ 国家统计局:《2000年第五次人口普查数据》. [2010-06-17]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-09).

- ^ 【特稿】人類非遺「羌年」在傳承保護中再現活力. 文汇网.

分享到: