辽观搬运和翻译的英文维基百科词条。与原维基百科词条同样遵循CC-BY-SA 4.0协议,在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。

中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。

本文基于英文词条线索,补充加入来自中文词条的内容。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目(点击这里了解更多),其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。 辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。 文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

目录

- 0. 概述

- 1. 发展历程 | Development

- 2. 设计 | Design

- 3. 子型号 | Variants

- 4. 运营者 | Operators

- 5. 意外和故障 | Accidents and incidents

- 6. 在展飞机 | Aircraft on display

- 7. 技术指标 | Specifications

- 8. 文化影响 | Cultural impact

- 9. 参见 / 相关条目

- 10. 参考文献

- 11. 延伸阅读 Further Reading

- 12. 外部链接

0. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

| Role 类型 | Wide-body jet airliner 宽体喷气式客机 |

|---|---|

| National origin 来源国 | United States 美国 |

| Manufacturer 制造商 | Boeing Commercial Airplanes 波音商用飞机公司 |

| First flight 首飞 | February 9, 1969 1969年2月9日 |

| Introduction 发布 | January 22, 1970, with Pan Am 1970年1月22日,由泛美航空执飞 |

| Status 现状 | In service (已停产),服役中 |

| Primary users 主要用户 | Atlas Air 阿特拉斯航空 Lufthansa 汉莎航空 Cargolux 卢森堡货运航空 UPS Airlines UPS航空 |

| Produced 在产年份 | 1968–2023 |

| Number built 生产数量 | 1,574 (including prototype) 1574,包括原型机 |

| Variants 子型号 | Boeing 747SP Boeing 747-400 Boeing 747-8 Boeing VC-25 Boeing E-4 747 Supertanker |

| Developed into 发展为 | Boeing Dreamlifter Boeing YAL-1 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft SOFIA |

波音747,又称为“珍宝客机”(Jumbo Jet)[6][7],是全世界首款生产出的宽体民航飞机,由美国波音民用飞机集团制造。波音747雏型的大小是1960年代被广泛使用的波音707的两倍[8]。1970年至2007年(A380投入服务)期间,波音747保持全世界载客量最高飞机的纪录长达37年。

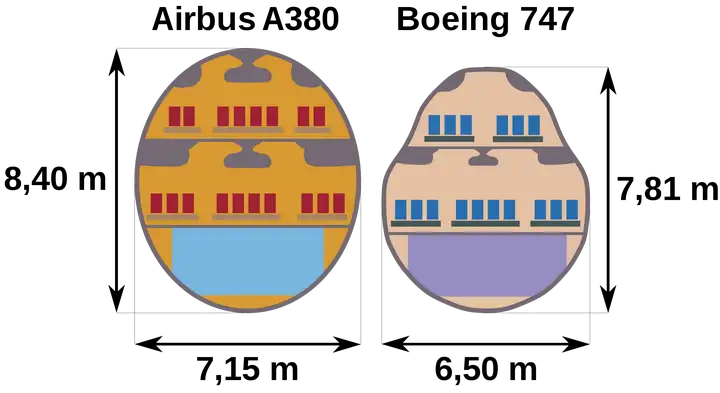

维基百科的图片说明:A380与波音747横截面对比

图片作者:法语维基百科的Steff

波音747是一款半双层四发动机飞机,可用于载客、载货、军事或其它用途,例如作为美国总统指挥专机和空军司令部。747上层甲板的设计令它的货机型号能够在机首加装货舱门,客机型号则可以增加额外座位,使得三级座舱设计(即是分为经济,商务和头等舱)的载客量达到416人,而双级舱设计的载客量则高达524人。747这种宽体客机在1969年横空出世,令民航载客量显著的增加,并降低了机票成本与价格,普罗大众环游世界也成为了可能,对于世界产生了巨大的影响。

The Boeing 747 is a large, long-range wide-body airliner designed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes in the United States between 1968 and 2023. After introducing the 707 in October 1958, Pan Am wanted a jet 2+1⁄2 times its size, to reduce its seat cost by 30%. In 1965, Joe Sutter left the 737 development program to design the 747. In April 1966, Pan Am ordered 25 Boeing 747-100 aircraft, and in late 1966, Pratt & Whitney agreed to develop the JT9D engine, a high-bypass turbofan. On September 30, 1968, the first 747 was rolled out of the custom-built Everett Plant, the world’s largest building by volume. The first flight took place on February 9, 1969, and the 747 was certified in December of that year. It entered service with Pan Am on January 22, 1970. The 747 was the first airplane called a “Jumbo Jet” as the first wide-body airliner.

参考译文:波音747是美国波音商用飞机公司在1968年至2023年间设计和制造的一款大型、远程宽体客机。在1958年10月推出707后,泛美航空公司希望拥有一款尺寸为707的2.5倍的喷气式飞机,以降低其座位成本30%。1965年,Joe Sutter离开737开发项目,开始设计747。1966年4月,泛美航空公司订购了25架波音747-100型飞机,同年晚些时候,普惠公司同意开发JT9D发动机,这是一种高涵道涡轮风扇发动机。1968年9月30日,第一架747从世界上最大的建筑——定制建造的埃弗雷特工厂驶出。第一次飞行发生在1969年2月9日,747于同年12月获得认证。它于1970年1月22日与泛美航空公司一起投入使用。由于是第一款宽体客机,747被称为“珍宝喷气机”。

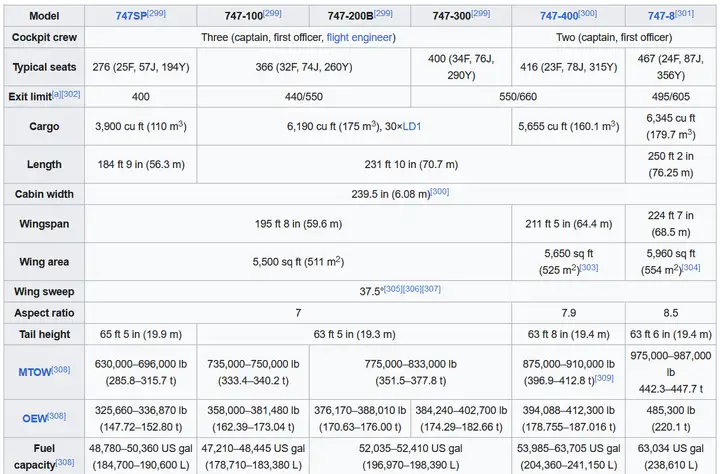

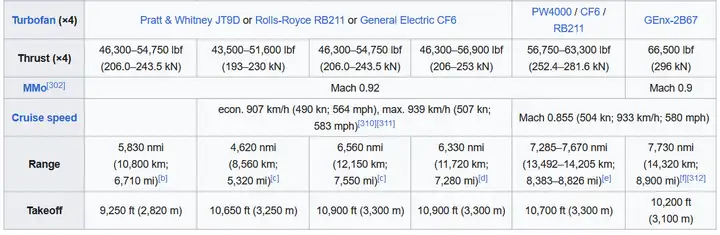

The 747 is a four-engined jet aircraft, initially powered by Pratt & Whitney JT9D turbofanengines, then General Electric CF6 and Rolls-Royce RB211 engines for the original variants. With a ten-abreast economy seating, it typically accommodates 366 passengers in three travel classes. It has a pronounced 37.5° wing sweep, allowing a Mach 0.85 (490 kn; 900 km/h) cruise speed, and its heavy weight is supported by four main landing gear legs, each with a four-wheel bogie. The partial double-deck aircraft was designed with a raised cockpit so it could be converted to a freighter airplane by installing a front cargo door, as it was initially thought that it would eventually be superseded by supersonic transports.

参考译文:波音747是一款四引擎喷气式飞机,最初由普惠JT9D涡轮风扇发动机提供动力,后来为原始版本配备了通用电气CF6和劳斯莱斯RB211发动机。它采用十排经济舱布局,通常可容纳366名乘客,分为三个旅行等级。它具有明显的37.5°翼展,可实现0.85马赫(490 kn; 900 km/h)的巡航速度,其沉重的重量由四个主起落架支撑,每个起落架上都有四个轮子。这款部分双层飞机的设计带有抬高的驾驶舱,因此可以通过安装前部货舱门将其转换为货运飞机,因为最初认为它最终将被超音速运输机取代。

Boeing introduced the -200 in 1971, with more powerful engines for a heavier maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) of 833,000 pounds (378 t) from the initial 735,000 pounds (333 t), increasing the maximum range from 4,620 to 6,560 nautical miles [nmi] (8,560 to 12,150 km; 5,320 to 7,550 mi). It was shortened for the longer-range 747SP in 1976, and the 747-300 followed in 1983 with a stretched upper deck for up to 400 seats in three classes. The heavier 747-400 with improved RB211 and CF6 engines or the new PW4000 engine (the JT9D successor), and a two-crew glass cockpit, was introduced in 1989 and is the most common variant. After several studies, the stretched 747-8 was launched on November 14, 2005, with new General Electric GEnx engines, and was first delivered in October 2011.

参考译文:波音公司在1971年推出了波音747-200型,其最大起飞重量(MTOW)从最初的735,000磅(333吨)增加到833,000磅(378吨),配备了更强大的发动机,最大航程从4,620海里(8,560公里或5,320英里)增加到6,560海里(12,150公里或7,550英里)。为了适应更长航程的波音747SP,1976年对飞机进行了缩短,1983年推出了波音747-300型,上层甲板加长,可容纳三个等级的最多400个座位。1989年推出的波音747-400型配备了改进的RB211和CF6发动机或新的PW4000发动机(JT9D的继任者),以及双人玻璃驾驶舱,是最常见的变体。经过多次研究,2005年11月14日推出了延长型的波音747-8,配备了新的通用电气GEnx发动机,并于2011年10月首次交付。

The 747 is the basis for several government and military variants, such as the VC-25 (Air Force One), E-4 Emergency Airborne Command Post, Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, and some experimental testbeds such as the YAL-1 and SOFIA airborne observatory.

参考译文:波音747还是几种政府和军用变体的基础,例如VC-25(空军一号)、E-4紧急空中指挥所、航天飞机运输机等。此外,还有一些实验性测试台,如YAL-1和SOFIA航空观测站。

80年代随着超音速客机的问世及持续发展,部分业界人士估计波音747将会慢慢退役[9],但直到1993年,波音747累计超过1,000架的订单使他们的预测落空[10]。停产前,1,574架波音747已被生产。[2]。波音747更推出最新型号747-8,已在2011年正式投入服务[11]。虽然747的载客量至2010年代为止非常兴盛,但因为双发动机中宽体客机带来的经济效益更好,加上四发动机的燃油效益仍然过低,2017年6月波音就宣布即将停产客运用的747-8,但仍继续生产货运用的747-8F及特殊型号(如空军一号、波音商务客机)。[12]

由于2019冠状病毒病疫情,导致航空运输需求锐减,波音于2020年7月宣布决定于2022年停产所有747系列飞机,并于2023年1月31日交付最后一架747-8F至亚特拉斯航空后正式停产,结束其长达54年的生产历史[13][14]。

Initial competition came from the smaller trijet widebodies: the Lockheed L-1011 (introduced in 1972), McDonnell Douglas DC-10 (1971) and later MD-11 (1990). Airbus competed with later variants with the heaviest versions of the A340 until surpassing the 747 in size with the A380, delivered between 2007 and 2021. Freighter variants of the 747 remain popular with cargo airlines. The final 747 was delivered to Atlas Air in January 2023 after a 54-year production run, with 1,574 aircraft built. As of January 2023, 64 Boeing 747s (4.1%) have been lost in accidents and incidents, in which a total of 3,746 people have died.

参考译文:最初的竞争来自较小的三喷气式宽体飞机:洛克希德L-1011(1972年推出)、麦道DC-10(1971年)和后来的MD-11(1990年)。空客公司与A340的最重版本竞争,直到A380在尺寸上超越747(2007年至2021年交付)。货运航空公司仍然喜欢使用747货机。最后一架747于2023年1月交付给Atlas Air,经过54年的生产线,共生产了1,574架飞机。截至2023年1月,共有64架波音747(占4.1%)在事故和事件中损失,总共造成3,746人死亡。

1. 发展历程 | Development

1.1 背景 | Background

图片题注:AirBridgeCargo Airlines Boeing 747-200F nose loading door open and cargo loader at Sheremetyevo International Airport

图片作者:Aleksandr Markin-点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:Sheremetyevo国际机场的AirBridgeCargo航空公司波音747- 200F型飞机的机头装卸门打开,货运装载机

在1963年,美国空军为开发一种宽体战略运输机而展开一连串的研究。虽然美国已经开始购入C-141“运输星”,但当局认为需要一款体积更大、性能更强的运输机,能够携带当时所有运输机都无法负载的特宽体货物。研究最终衍生出“CX-X”(Cargo, Experimental, no number,货运、实验性的、无编号)设计,载重量达180,000磅,速度达0.75马赫(500英里或805千米),载重115,000磅的航程达5,000海里(9,260千米),载货空间为宽17英尺(5.18米)、高13.5英尺(4.11米)和长100英尺(30.5米)。

CX-X早期的设计,是由六台发动机提供推力,但是CX-X的设计相比C-141,未显得有任何大进步而值得开发,于是一款称为“重型后勤系统”(Heavy Logistics System, CX-HLS)的飞机计划在1964年4月27日诞生。CX-HLS由四台发动机提供推力,增加了发动机推力,并提升了燃油效率。1964年5月18日,机身提案到达了波音、道格拉斯、洛克希德、通用动力和马丁·玛丽埃塔公司手上,经过筛选后,波音、道格拉斯和洛克希德给予关于机身的附加合约,发动机由普惠或通用电气航空公司提供。[15]

三间公司的提案各有一些共通特色,其中一个与747外型有点相似。CX-HLS的设计可以携带重型货物,但是驾驶舱位于传统位置,当飞机坠毁时,货物会向前推而压伤飞行员。三家公司都因这问题而困扰,于是道格拉斯公司便在机翼前上方增加一个小吊舱;洛克希德公司的设计是把驾驶舱放在上层,采用高单翼设计,四台发动机吊挂在主翼下;波音公司的设计便是增加一个较大的吊舱。[16]

1965年,洛克希德公司的设计和通用电气的发动机成功地夺得美国空军的订单,成为后来的C-5“银河”运输机。[17]

1.2 客机方案 | Airliner proposal

The 747 was conceived while air travel was increasing in the 1960s.[5] The era of commercial jet transportation, led by the enormous popularity of the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8, had revolutionized long-distance travel.[5][6] In this growing jet age, Juan Trippe, president of Pan Am, one of Boeing’s most important airline customers, asked for a new jet airliner 2+1⁄2 times size of the 707, with a 30% lower cost per unit of passenger-distance and the capability to offer mass air travel on international routes.[7] Trippe also thought that airport congestion could be addressed by a larger new aircraft.[8]

参考译文:在20世纪60年代,随着航空旅行需求的增长,波音747应运而生。当时,商业喷气式飞机交通时代已经到来,波音707和道格拉斯DC-8的广泛受欢迎为长途旅行带来了革命性的变革。在这个不断发展的喷气式飞机时代,泛美航空公司(Pan Am)总裁胡安·特里普(Juan Trippe)向波音公司提出了一个要求,他希望这种新型喷气式客机的尺寸是波音707的2.5倍,每单位乘客距离的成本降低30%,并具备在国际航线上提供大规模空中旅行的能力。特里普还认为,大型新飞机可以解决机场拥堵问题。

图片题注:The cockpit of Iran Air Boeing 747-200 as seen on approach to Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport at night.

图片作者:Shahram Sharifi-点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:伊朗航空公司波音747-200的驾驶舱在夜间降落德黑兰梅赫拉巴德机场时的景象。

In 1965, Joe Sutter was transferred from Boeing’s 737 development team to manage the design studies for the new airliner, already assigned the model number 747.[9] Sutter began a design study with Pan Am and other airlines to better understand their requirements. At the time, many thought that long-range subsonic airliners would eventually be superseded by supersonic transport aircraft.[10] Boeing responded by designing the 747 so it could be adapted easily to carry freight and remain in production even if sales of the passenger version declined.

参考译文:1965年,乔·萨特(Joe Sutter)从波音737开发团队调任,负责新客机的设计研究,该客机已被分配了747的型号。[9] 萨特开始与泛美航空和其他航空公司进行设计研究,以更好地了解他们的需求。当时,许多人认为长程亚音速客机最终将被超音速运输机取代。[10] 波音对此的回应是设计747,以便它可以方便地改装以运载货物,即使乘客版本销售下降,也可以继续生产。

1965年,乔·萨特(Joe Sutter)由波音737开发小组调至管理波音747的开发计划[20],他与泛美航空等公司接洽,并了解他们对新飞机的需求。业界认为,波音747最终会被超音速客机取代[21],于是波音公司便回应,即使747不受旅客欢迎,也可以用来运载货物。波音747的货运角色,明确地显示它能支援一般船只所用的标准货柜(TEU)尺寸为前方8×8尺、长20或40尺,能够支援2x2x2或2x2x3货柜,此货柜款式与CX-HLS计划相似。

1966年4月,泛美航空订购了25架波音747-100,总共价值5亿2500万美元,签署仪式在西雅图举行,刚好正是波音公司成立50周年,泛美航空总裁胡安·特里普说:“相比起洲际弹道导弹,波音747是人类的和平武器”,此话是根据当时波音747项目的高层马尔科姆·斯塔姆帕(Malcolm T. Stamper),在受访时所说[22]。因为泛美航空是波音747启动客户之一[1][23],因此泛美航空有能力改变747的设计和发展[24]。

1.3 设计工作 | Design effort

维基百科的图片说明:早期波音747的上层空间多用作头等舱乘客休息室

图片作者:Clemens Vasters from Viersen, Germany-点击这里访问原图链接

Ultimately, the high-winged CX-HLS Boeing design was not used for the 747, although technologies developed for their bid had an influence.[17] The original design included a full-length double-deck fuselage with eight-across seating and two aisles on the lower deck and seven-across seating and two aisles on the upper deck.[18][19]

参考译文:最终,波音公司并未采用高翼设计的CX-HLS作为747的设计,尽管他们为竞标开发的一些技术产生了影响。[17]最初的设计包括一个全长双层机身,下层有八排座位和两条走道,上层有七排座位和两条走道。[18][19]

However, concern over evacuation routes and limited cargo-carrying capability caused this idea to be scrapped in early 1966 in favor of a wider single deck design.[14] The cockpit was therefore placed on a shortened upper deck so that a freight-loading door could be included in the nose cone; this design feature produced the 747’s distinctive “hump”.[20] In early models, what to do with the small space in the pod behind the cockpit was not clear, and this was initially specified as a “lounge” area with no permanent seating.[21] (A different configuration that had been considered to keep the flight deck out of the way for freight loading had the pilots below the passengers, and was dubbed the “anteater”.)[22]

参考译文:然而,对疏散路线的担忧和有限的货运能力导致这个想法在1966年初被废弃,转而采用更宽的单层设计。[14]因此,驾驶舱被放置在缩短的上层,以便在机头锥体中包括一个货物装载门;这个设计特征产生了747独特的”驼峰”。[20]在早期的模型中,如何处理驾驶舱后面的小空间并不明确,最初被指定为一个没有固定座位的”休息室”区域。[21](另一种考虑将飞行甲板移开以便于货物装载的配置让飞行员位于乘客下方,被称为”食蚁兽”。)[22]

而在747之前采用上层驾驶舱隆起设计的飞机还有20世纪60年代初的ATL-98运输机及AW660大商船运输机。

图片题注:A Pratt & Whitney JT9Dturbofan on the wing of the Boeing 747 prototype.

图片作者:Mgw89

参考译文:波音747原型机翼上的普惠JT9D涡轮风扇发动机。

波音747是采用高涵道比涡轮风扇发动机[28],这种发动机的耗油量较低,推力亦较大。通用电气公司虽然是高涵道比涡扇发动机的先驱者,却因为专注于C-5银河的发动机的开发而没有参与波音747发动机的开发[29][30],而普惠公司也一样要专注于C-5银河的发动机的开发,可是在1966年出现了转机,普惠公司与泛美航空同意研发一款新的发动机,称为JT9D,作为波音747的发动机[30]。

The project was designed with a new methodology called fault tree analysis, which allowed the effects of a failure of a single part to be studied to determine its impact on other systems.[14] To address concerns about safety and flyability, the 747’s design included structural redundancy, redundant hydraulicsystems, quadruple main landing gear and dual control surfaces.[26] Additionally, some of the most advanced high-lift devices used in the industry were included in the new design, to allow it to operate from existing airports. These included Krueger flaps running almost the entire length of the wing’s leading edge, as well as complex three-part slotted flaps along the trailing edge of the wing.[27][28] The wing’s complex three-part flaps increase wing area by 21% and lift by 90% when fully deployed compared to their non-deployed configuration.[29]

参考译文:该项目采用了一种名为故障树分析的新方法进行设计,该方法允许研究单个部件失效的影响,以确定其对其他系统的影响。[14]为了解决安全和飞行性能方面的问题,747的设计包括结构冗余、冗余液压系统、四轮主起落架和双控制面。[26]此外,新设计中还包括了业界最先进的高升力装置,使其能够从现有机场起降。这些装置包括几乎覆盖整个机翼前缘的克鲁格襟翼,以及沿机翼后缘的复杂三段开缝襟翼。[27][28]与非展开构型相比,机翼的复杂三段襟翼在完全展开时可将机翼面积增加21%,升力增加90%。[29]

Boeing agreed to deliver the first 747 to Pan Am by the end of 1969. The delivery date left 28 months to design the aircraft, which was two-thirds of the normal time.[30] The schedule was so fast-paced that the people who worked on it were given the nickname “The Incredibles”.[31]Developing the aircraft was such a technical and financial challenge that management was said to have “bet the company” when it started the project.[14] Due to its massive size, Boeing subcontracted the assembly of subcomponents to other manufacturers, most notably Northrop and Grumman (later merged into Northrop Grumman in 1994) for fuselage parts and trailing edge flaps respectively, Fairchild for tailplane ailerons,[32] and Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV) for the empennage.[33][34]

参考译文:波音公司同意在1969年底前向泛美航空公司交付首架747飞机。这个交付日期给飞机设计留下了28个月的时间,这相当于正常时间的三分之二。[30]由于进度非常快,参与这个项目的人被戏称为“超人”。[31]开发这款飞机在技术和财务上都是一个巨大的挑战,据说管理层在启动项目时已经“押上了公司的赌注”。[14]由于其巨大的尺寸,波音将子组件的组装分包给其他制造商,最著名的是诺斯罗普和格鲁门(后来于1994年合并为诺斯罗普·格鲁曼),分别负责机身部件和后缘襟翼,费尔柴尔德负责尾翼副翼,[32]以及LTV公司负责尾部结构。[33][34]

波音747计划对波音公司来说是一项赌注,是金钱和科技的赌注[1]。1967年,波音公司同意于1969年末把首架747交付给泛美航空,但波音距离交付时间只剩下28个月[32],需要加快进度完成,因此人们给此工程别名为“不可思议”(The Incredibles)[33]。

1.4 生产工厂 | Production plant

图片题注:Interior of Boeing Factory, Seattle

图片作者:Meutia Chaerani / Indradi Soemardjan – 点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:西雅图波音工厂内部

波音公司并没有足够的地方生产这款宽体飞机,因此波音公司需要建造一个新厂房,新厂房地点将会在50个侯选城市中的其中一个[34]。1966年,波音公司于华盛顿州西雅图以北约30英里处的艾佛里特佩恩机场[35]买了一块780英亩(约3.156平方千米)的土地作为新厂房[36],新厂房是全世界最大的飞机厂房[35],而整平新厂房的地基是需要移动超过310万立方米土地[37]。

Developing the 747 had been a major challenge, and building its assembly plant was also a huge undertaking. Boeing president William M. Allen asked Malcolm T. Stamper, then head of the company’s turbine division, to oversee construction of the Everett factory and to start production of the 747.[38] To level the site, more than four million cubic yards (three million cubic meters) of earth had to be moved.[39] Time was so short that the 747’s full-scale mock-up was built before the factory roof above it was finished.[40] The plant is the largest building by volume ever built, and has been substantially expanded several times to permit construction of other models of Boeing wide-body commercial jets.[36]

参考译文:开发747飞机是一项重大挑战,建造其组装厂也是一项巨大的工程。波音公司总裁威廉·M·艾伦(William M. Allen)要求当时负责公司涡轮部门工作的马尔科姆·T·斯坦普(Malcolm T. Stamper)监督埃弗雷特工厂的建设并开始生产747飞机。[38]为了平整场地,需要移动超过400万立方码(300万立方米)的土壤。[39]由于时间紧迫,747飞机的全尺寸模型在工厂屋顶完工之前就已经建成。[40]该工厂是有史以来建造的最大建筑物,已经多次大幅扩建,以允许建造其他型号的波音宽体商用喷气式飞机。[36]

1.5 飞行测试 | Flight testing

图片题注:The Boeing 747, being displayed to the public for the first time

图片来源:SAS Scandinavian Airlines–点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:首次向公众展示的波音747飞机。

在首架波音747完成装配之前,已经展开了测试工作。其中一项重要的测试是逃生测试,560人需要在限定时间内全部从模拟机舱撤离。首次逃生测试用了2分半钟,比美国联邦航空局要求的90秒慢许多,当中有些人更受了伤,随后的测试虽然达到联邦航空局的要求,但招来的是有更多人受伤,伤者大多是从上层甲板逃生的[40]。

当747仍在建造时,波音公司设计一项特别的训练计划称为“韦德尔的马车”(Waddell’s Wagon,一名747测试飞行员杰克·韦德尔为它命名)的模拟驾驶舱,该计划允许飞行员模拟在驾驶舱练习滑行此宽体飞机[41]。

In 1968, the program cost was US$1 billion[43] (equivalent to $6 billion in 2021 dollars). On September 30, 1968, the first 747 was rolled out of the Everett assembly building before the world’s press and representatives of the 26 airlines that had ordered the airliner.[44]

参考译文:1968年,该项目的成本为10亿美元(相当于2021年的60亿美元)。1968年9月30日,第一架747在埃弗里特组装厂前推出了世界媒体和已订购该客机的26家航空公司的代表。[44]

接下来的数个月,波音公司要准备747的飞行测试。波音747于1969年2月9日首飞,由杰克·韦德尔(Jack Waddell)和布里恩·威格(Brien Wygle)操作[43][44],杰斯·沃利克(Jess Wallick)担任飞行工程师。尽管襟翼出现了一个小问题,不过整个飞行过程是十分良好,且不会出现“荷兰滚”情况[45][需要解释]。

1.6 问题、推迟和认证 | Issues, delays and certification

维基百科的图片说明:The 747’s 16-wheel main landing gear

图片作者:Arpingstone-Photographed by Adrian Pingstone in August 2002 and released to the public domain.

参考译文:747的16轮主起落架

图片题注:Wing and fuselage undercarriages on aSingapore AirlinesBoeing 747-400landing atLondon Heathrow Airport, England. The last three letters of the registration (9V-SMT) can just be seen on the fuselage in the lower left.

参考译文:一架新加坡航空公司的波音747-400降落在伦敦希思罗机场,机翼和机身底部的起落架清晰可见。在机身左下方可以看到注册编号的最后三个字母(9V-SMT)。

During later stages of the flight test program, flutter testing showed that the wings suffered oscillation under certain conditions. This difficulty was partly solved by reducing the stiffness of some wing components. However, a particularly severe high-speed flutter problem was solved only by inserting depleted uranium counterweights as ballast in the outboard engine nacelles of the early 747s.[48] This measure caused anxiety when these aircraft crashed, for example El Al Flight 1862 at Amsterdam in 1992 with 622 pounds (282 kg) of uranium in the tailplane (horizontal stabilizer).[49][50]

参考译文:在飞行测试计划的后期阶段,颤振测试显示,在某些条件下,机翼会出现振荡。这个问题部分通过降低某些机翼组件的刚度得到解决。然而,一个特别严重的高速颤振问题,只能通过在早期747的外侧发动机舱内插入贫化铀配重作为压舱物来解决。[48]当这些飞机坠毁时,这种措施引起了人们的焦虑,例如1992年在阿姆斯特丹发生的El Al 1862航班,尾翼(水平稳定器)中有622磅(282公斤)的铀。[49][50]

747的飞行测试计划因为JT9D发动机出现问题而受阻,其中的困难包括因油门高速移动而引致发动机熄火和涡轮机壳在短期使用后即出现变形。[49]这些问题令波音747的交付延期数月,并使30多架等待安装新发动机的客机在厂房停滞。后来五架测试飞机中的一架在尝试降落波音公司位于伦顿的厂房──伦顿市机场──时严重受损,747的测试计划因此再度延迟;当时飞机的测试装备被移除并改装为客舱,降落时在短跑道外提前接地,起落架飞脱。[50]这些问题未能阻止波音公司的747飞机去参加1969年的巴黎航空展,该航空展令波音747首次公开亮相[51]。1969年12月,波音747完成了美国联邦航空局的测试,表示它能正式投入服务[52]。

The huge cost of developing the 747 and building the Everett factory meant that Boeing had to borrow heavily from a banking syndicate. During the final months before delivery of the first aircraft, the company had to repeatedly request additional funding to complete the project. Had this been refused, Boeing’s survival would have been threatened.[15][57] The firm’s debt exceeded $2 billion, with the $1.2 billion owed to the banks setting a record for all companies. Allen later said, “It was really too large a project for us.”[58] Ultimately, the gamble succeeded, and Boeing held a monopoly in very large passenger aircraft production for many years.[59]

参考译文:开发747和建造埃弗雷特工厂的巨大成本意味着波音公司不得不大量向银行财团借款。在交付首架飞机之前的最后几个月,该公司不得不多次请求额外资金以完成项目。如果被拒绝,波音的生存将受到威胁。[15][57] 公司的债务超过20亿美元,其中欠银行的12亿美元创下了所有公司的历史记录。艾伦后来表示:“这对我们来说确实是一个规模太大的项目。”[58] 最终,这场赌博成功了,波音公司在大型客机生产方面垄断了多年。[59]

1.7 投入服务 | Entry into service

图片题注:First Lady Pat Nixon christens the first Boeing 747, Clipper Young America, Reg# N736PA, at Dulles Airport, January 1970. This aircraft would later be destroyed in the Tenerife Airport disaster. WHPO 2749-18

图片来源:White House Photo Office-US government, Executive Office of the PresidenT

参考译文:第一夫人帕特·尼克松于1970年1月在杜勒斯机场为首架波音747客机“年轻的美洲号”(Clipper Young America,注册号N736PA)主持命名仪式。这架飞机后来在特内里费机场灾难中被摧毁。WHPO 2749-18

在1970年1月15日,美国第一夫人帕特·尼克松(Pat Nixon)在华盛顿杜勒斯国际机场(Dulles International Airport)主持泛美航空首架747的命名仪式,该飞机在一星期后投入服务,负责纽约–伦敦航线[55]。该次飞行原定是在1月21日进行,但由于负责该趟飞行的747发动机过热不能参与,所以足足耽误了六小时才由另一架747负责飞行,而原本故障的747则回厂检修[56]。

747投入服务的过程十分顺利,事循证明了规模较小的机场也一样可以容纳747[57],虽然出现了些技术小问题,但都很快地解决了[58]。自泛美航空的747投入服务后,其它订购了747的航空公司争相投入服务,以提高自己的竞争力[59][60]。波音估计逾半订购747早期型号的航空公司,都是把它们用作首席执行官途航线,而非高载客量的航线[61]。虽然波音747的人均运营成本相对较低,但要高载客率才有利可图,根据计算,一架70%载客率的747的燃油耗量是一架全满747的95%[62]。

维基百科的图片说明:波音747-100和-200型的楼梯是采用螺旋型设计

图片作者:Akradecki

Nonetheless, many flag-carriers purchased the 747 due to its prestige “even if it made no sense economically” to operate. During the 1970s and 1980s, over 30 regularly scheduled 747s could often be seen at John F. Kennedy International Airport.[69]

参考译文:尽管如此,许多航空公司仍然购买747,因为它的声望“即使从经济上讲没有意义”,也可以运营。在1970年代和1980年代,经常可以看到超过30架定期的747飞机停在约翰·肯尼迪国际机场。[69]

The recession of 1969–1970, despite having been characterized as relatively mild, greatly affected Boeing. For the year and a half after September 1970, it only sold two 747s in the world, both to Irish flag carrier Aer Lingus.[70][71] No 747s were sold to any American carrier for almost three years.[58]

参考译文:1969年至1970年的衰退,尽管被描述为相对温和,但对波音公司产生了巨大影响。在1970年9月之后的一年半时间里,波音公司仅在全球售出了两架747飞机,这两架飞机都卖给了爱尔兰的旗舰航空公司爱尔兰航空。[70][71]在接下来的近三年时间里,波音公司没有向任何美国航空公司出售过747飞机。[58]

1973年,石油危机爆发,随着运营成本上升,一些航空公司发现747的运营对他们来说几乎无利可图,于是便使用同期的DC-10、L-1011或较后期的波音767和A300代替747[63],有些航空公司虽然继续使用747,但他们会拆去一些座位,改装成为酒吧等,美国航空在1983年把747改装成为货机,并用自己的747与泛美航空的DC-10交换[64],而达美航空亦在数年后把747除役[65]。

Later, Delta acquired 747s again in 2008 as part of its merger with Northwest Airlines, although it retired the Boeing 747-400fleet in December 2017.[75]

参考译文:后来,达美航空公司在2008年收购了747飞机,作为其与西北航空公司合并的一部分,尽管它在2017年12月退役了波音747-400机队。 [75]

International flights bypassing traditional hub airports and landing at smaller cities became more common throughout the 1980s, thus eroding the 747’s original market.[76] Many international carriers continued to use the 747 on Pacific routes.[77] In Japan, 747s on domestic routes were configured to carry nearly the maximum passenger capacity.[78]

参考译文:在20世纪80年代,绕过传统枢纽机场并在较小城市降落的国际航班变得越来越普遍,从而侵蚀了747的原始市场。[76]许多国际航空公司继续在太平洋航线上使用747。[77]在日本,国内航线上的747被配置为承载近最大乘客容量。[78]

1980年代,国际航班经传统转运站而到达其它小城市越来越普及[66],这趋势虽然削弱了747的竞争力,但仍有许多航空公司继续使用747来运营太平洋航线[67];在国内线需求极高的日本,747是日本国内线的主力机队[68]。

由于波音747的高知名度与广泛运用,经常被用作为电影(尤其是空难电影)的背景或道具,曾经有747入镜的影片不计其数,例在1996年上映的电影《747绝地悍将》(Executive Decision)[69]、1997年上映的电影《空军一号》(Air Force One)[70]、2006年上映的电影《毒蛇吓机》(Snakes on a Plane)[71]和2007年上映的电影《死亡客机》(Flight of the Living Dead: Outbreak on a Plane)。除了电影,在不少欧美、日韩动漫影视和游戏作品里面,都有747的身影出现。在著名第一人称射击游戏《反恐精英》之中有3张相关地图(cs_747、zm_747、dm_747)。在奇幻系轻小说《Fate/Apocrypha》中被黑之阵营大量用以追击夺走大圣杯的红之阵营。在3D动画电影《赛车总动员2》里面,闪电麦昆和朋友们乘坐那架客机也是747拟人化而来。在《名侦探柯南》剧场版《银翼的魔术师》、《业火的向日葵》中的飞机也是波音747。而波音也曾经在著名的社交平台新浪微博发起一条名为“寻找747”的微博,引起广大航空爱好者的强烈关注。

1.8 升级的747版本 | Improved 747 versions

维基百科的图片说明:Stretched upper deck cabin of later 747s with six-abreast seating

图片作者:Alex Beltyukov – RuSpotters Team-点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:后期747客机的上层甲板舱宽敞,可容纳六人并排就座。

波音开发完了747-100之后,再开发一款拥有较高起飞重量的-100B和高载客量的短程型-SR(多用于日本国内航线,同时因频繁的起落次数而加强了起落架)[72],最大起飞重量提高表示能够装载更多燃料飞行得更远,相当于今天的-ER(波音/麦道)/IGW(麦道)/HGW(空客)[73]。后期还有-100SUD(延长上层甲板用于载客)型可供改造。-200型在1971年投入服务,采用更高效率的发动机和提高了最大起飞重量,该型号的用途可仔细分为客运、货运(-F),客货转换(-C)和客货混合(M,即Combi)[72]。747-200同样可以改造为-200SUD。1970年代中期,波音公司又开发了一款缩短机身但航程较远的-SP(SpecialPerformance)[74]。

1980年波音公司又开发了-300型,主要是增加了载客量,计划代号为747SUD,意即“延长上层甲板”(StretchedUpperDeck)[75],但此代号很快地更名为747EUD(ExtendedUpperDeck)[76],名称虽然不同,意思仍旧一样。首架747-300在1983年建造,除了延长上层甲板,还提高航速和载客量,并设有客运、客货混合、SR和后期改造的货运型号[72]。

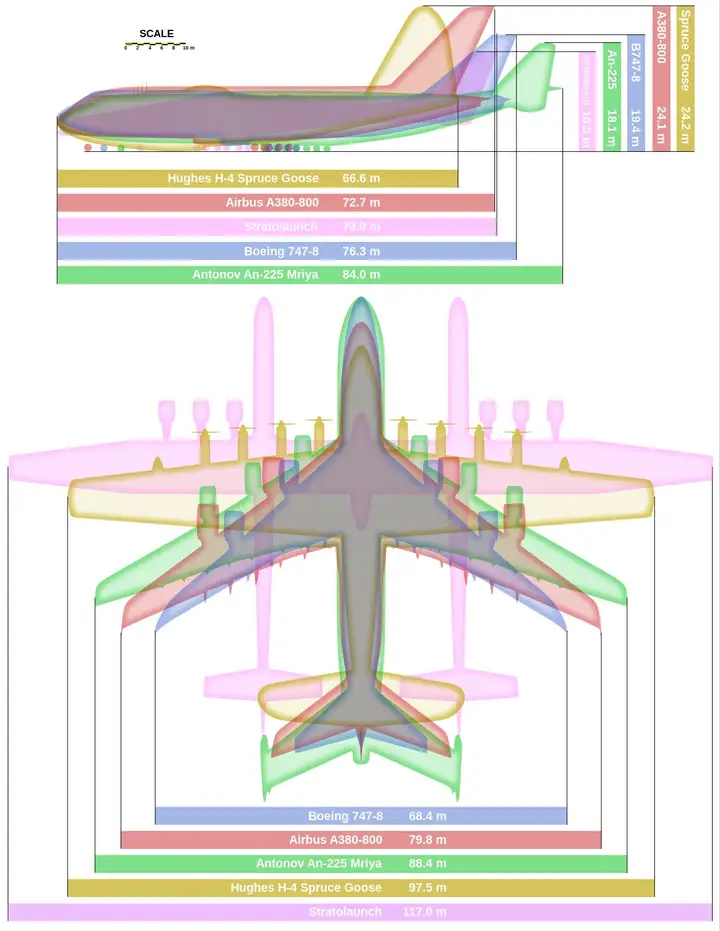

图片题注:史上四种最大巨型飞机迭合比较图:休斯H-4 Spruce Goose大力士型运输机(具最大翼展)、安托诺夫An-225运输机(最大体积)、波音747-8洲际飞机(最大款式之波音747空中巨无霸)、以及空中客车A380-800型客机(现今最大型客机)。

图片作者:Clem Tillier(clem AT tillier.net)

维基百科的图片说明:Launch Customer Northwest Airlines introduced the 747-400 in 1989.

图片作者:Paul Spijkers-点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:启动用户西北航空公司于1989年引进了747-400。

1985年,波音公司再度开发一款新型号名为747-400[77],该型号配备玻璃座舱[78],需要的飞行员由三人减少至两人。随着研发成本上升,应航空公司要求而加入的新技术,再加上员工经验不足使飞机延期[1],使-400型在1989年才能投入服务[79]

In 1991, a record-breaking 1,087 passengers were flown in a 747 during a covert operation to airlift Ethiopian Jews to Israel.[88] Generally, the 747-400 held between 416 and 524 passengers.[89] The 747 remained the heaviest commercial aircraft in regular service until the debut of the Antonov An-124Ruslan in 1982; variants of the 747-400 surpassed the An-124’s weight in 2000. The Antonov An-225 Mriya cargo transport, which debuted in 1988, remains the world’s largest aircraft by several measures (including the most accepted measures of maximum takeoff weight and length); one aircraft has been completed and was in service until 2022. The Scaled Composites Stratolaunchis currently the largest aircraft by wingspan.[90]

参考译文:1991年,在一次秘密行动中,一架波音747客机以创纪录的1087名乘客数量,将埃塞俄比亚犹太人空运到以色列。[88]一般来说,波音747-400的载客量在416至524人之间。[89]直到1982年安东诺夫An-124鲁斯兰运输机问世之前,波音747一直是常规服务中最重的商用飞机;747-400的各种型号在2000年超过了An-124的重量。安东诺夫An-225 Mriya货运飞机于1988年首次亮相,根据多项指标(包括最大起飞重量和长度),它仍然是世界上最大的飞机;其中一架飞机已经完成并一直使用到2022年。目前,Scaled Composites Stratolaunch是翼展最大的飞机。[90]

1.9 进一步发展 | Further developments

维基百科的图片说明:747-400 main deck economy class seating in 3–4–3 layout

图片作者:Altair78

参考译文:747-400主甲板经济舱采用3-4-3布局。

继B747-400之后,波音公司有意再延长747。1996年,波音公司宣布波音747-500X和波音747-600X计划[80],新计划需要约50亿美元去开发[80],但因为航空公司不感兴趣而没有执行该计划[81]。在2000年,波音公司再度宣布新的747X和747X衍生型号以回应空中客车的A3XX,同样地因航空公司不感兴趣而没有执行,波音便在2001年宣布开发音速巡航者以代替747X[82],但航空公司不感兴趣而停止开发,取而代之的是波音787[83];然而,那些计划亦不是一无是处,有些概念应用在波音747-400ER上[84]。波音放弃多个计划后,有业界对波音公司的新飞机计划有点担忧[85],但在2004年,波音宣布一个新的747计划,该计划终于被波音采用了,新747计划与747-X相似,当中有些技术更是改良自波音787技术。

图片题注:Lufthansa Boeing 747-8

图片作者:Kiefer.from Frankfurt, Germany-点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:汉莎航空波音747-8

On November 14, 2005, Boeing announced it was launching the 747 Advanced as the Boeing 747-8.[98]The last 747-400s were completed in 2009.[99] As of 2011, most orders of the 747-8 were for the freighter variant. On February 8, 2010, the 747-8 Freighter made its maiden flight.[100] The first delivery of the 747-8 went to Cargolux in 2011.[101][102] The first 747-8 Intercontinental passenger variant was delivered to Lufthansa on May 5, 2012.[103] The 1,500th Boeing 747 was delivered in June 2014 to Lufthansa.[104]

参考译文:2005年11月14日,波音公司宣布推出747-8,即747升级版。[98]最后一架747-400于2009年完成。[99]截至2011年,747-8的大部分订单是货机版本。2010年2月8日,747-8货机进行了首次试飞。[100] 747-8的首次交付是在2011年交付给Cargolux航空公司。[101][102]第一个747-8洲际客运版本于2012年5月5日交付给德国汉莎航空公司。[103]第1500架波音747于2014年6月交付给德国汉莎航空公司。[104]

在2005年11月14日,波音宣布新开发747-8[86],而波音亦希望对手A380延期交付会使747-8的订单有所增长。两家空中客车买家与波音公司附加合约订购747-8[87][88],两家订购了A380的公司宣布取消A380订单,但亦有少数航空公司会接受A380延期交付或考虑订购747-8或B777F[89][90]。

In January 2016, Boeing stated it was reducing 747-8 production to six a year beginning in September 2016, incurring a $569 million post-tax charge against its fourth-quarter 2015 profits. At the end of 2015, the company had 20 orders outstanding.[105][106] On January 29, 2016, Boeing announced that it had begun the preliminary work on the modifications to a commercial 747-8 for the next Air Force One presidential aircraft, then expected to be operational by 2020.[107]

参考译文:2016年1月,波音公司表示,从2016年9月开始,将把747-8的生产量减少到每年6架,这将使其2015年第四季度的利润减少5.69亿美元。截至2015年底,该公司仍有20个订单未完成。[105][106] 2016年1月29日,波音公司宣布已开始对下一架空军一号总统飞机的商业747-8进行修改的初步工作,预计将于2020年投入使用。[107]

On July 12, 2016, Boeing announced that it had finalized an order from Volga-Dnepr Group for 20 747-8 freighters, valued at $7.58 billion (~$8.49 billion in 2021) at list prices. Four aircraft were delivered beginning in 2012. Volga-Dnepr Group is the parent of three major Russian air-freight carriers – Volga-Dnepr Airlines, AirBridgeCargo Airlines and Atran Airlines. The new 747-8 freighters would replace AirBridgeCargo’s current 747-400 aircraft and expand the airline’s fleet and will be acquired through a mix of direct purchases and leasing over the next six years, Boeing said.[108]

参考译文:2016年7月12日,波音公司宣布已完成伏尔加-第聂伯集团订购的20架747-8货机的订单,按标价计算价值为75.8亿美元(约合2021年的84.9亿美元)。四架飞机于2012年开始交付。伏尔加-第聂伯集团是俄罗斯三大航空货运公司的母公司,分别是伏尔加-第聂伯航空公司、AirBridgeCargo航空公司和Atran航空公司。波音公司表示,新的747-8货机将取代AirBridgeCargo目前的747-400飞机,并扩大该航空公司的机队规模。这些新飞机将在未来六年内通过直接购买和租赁的方式获得。[108]

在2007年A380投入服务之前,波音747曾是全世界载客量最高的飞机[91],在1991年的所罗门行动中,一架以色列航空波音747破纪录地运送了1087名乘客[92]。波音747曾是全世界最重的飞机直至1982年An-124运输机的出现。至于拥有翼展最长的飞机,则是由只飞行过一次的休斯H-4大力神在长期占据此名誉[93],但未来将被波音777X系列代替成为翼展最长的飞机。

一些747被改装用作特别用途,通用电气公司拥有1架747-100(编号N747GE,已退役)用作测试自己的发动机[94][95],一架由长青国际航空改装的747用作救火之用[94]。波音747客机停产后将由Y3计划取代。

1.10 停产 | End of production

虽然波音747这种超大载客量珍宝客机曾经带来商业飞行的革命,但基于较大油耗和乘客量不佳等因素,而且现代更符合燃油效益的双发动机飞机不断推陈出新,波音公司终于在2017年6月宣布,被誉为“空中女王”的747飞机将全面退出客机市场,并全面由波音777、787替代,只留下货机和特殊用途飞机,如空军一号[96]。

On July 27, 2016, in its quarterly report to the Securities and Exchange Commission, Boeing discussed the potential termination of 747 production due to insufficient demand and market for the aircraft.[109] With a firm order backlog of 21 aircraft and a production rate of six per year, program accounting had been reduced to 1,555 aircraft.[110] In October 2016, UPS Airlines ordered 14 -8Fs to add capacity, along with 14 options, which it took in February 2018 to increase the total to 28 -8Fs on order.[111][112] The backlog then stood at 25 aircraft, though several of these were orders from airlines that no longer intended to take delivery.[113]

参考译文:2016年7月27日,波音公司在向美国证券交易委员会提交的季度报告中,讨论了由于飞机需求和市场不足可能导致747停产的问题。[109] 当时,波音公司有21架飞机的订单积压,每年生产6架飞机,项目核算已减少到1,555架飞机。[110] 2016年10月,UPS航空公司订购了14架-8F以增加运力,并在2018年2月选择了14架飞机,将其总数增加到28架-8F。[111][112] 当时的订单积压为25架飞机,尽管其中有几笔是来自不再打算接收交付的航空公司的订单。[113]

受新冠肺炎疫情影响,部分航空公司将部分747客机全数退役,亦有部分将全数747-8客机封存直至航空业恢复正常。2020年7月6日,波音正式宣布将停产747(包括目前仍在生产的747-8系列),最后一架747于2022年出厂。

On July 2, 2020, it was reported that Boeing planned to end 747 production in 2022 upon delivery of the remaining jets on order to UPS and the Volga-Dnepr Group due to low demand.[114] On July 29, 2020, Boeing confirmed that the final 747 would be delivered in 2022 as a result of “current market dynamics and outlook” stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, according to CEO David Calhoun.[115] The last aircraft, a 747-8F for Atlas Air, rolled off the production line on December 6, 2022,[116] and was delivered on January 31, 2023.[117] Boeing hosted an event at the Everett factory for thousands of workers as well as industry executives to commemorate the delivery.[118]

参考译文:2020年7月2日,据报道,由于需求低迷,波音计划在2022年向UPS和伏尔加-第聂伯集团交付剩余的747订单后停产。[114] 2020年7月29日,波音首席执行官大卫·卡尔霍恩确认,由于COVID-19大流行导致的“当前市场动态和前景”,最后一架747将于2022年交付。[115] 最后一架747-8F飞机于2022年12月6日下线,并于2023年1月31日交付给Atlas Air航空公司。[116][117] 波音在埃弗雷特工厂举办了一场活动,邀请了数千名工人和行业高管参加,以纪念这一时刻。[118]

2. 设计 | Design

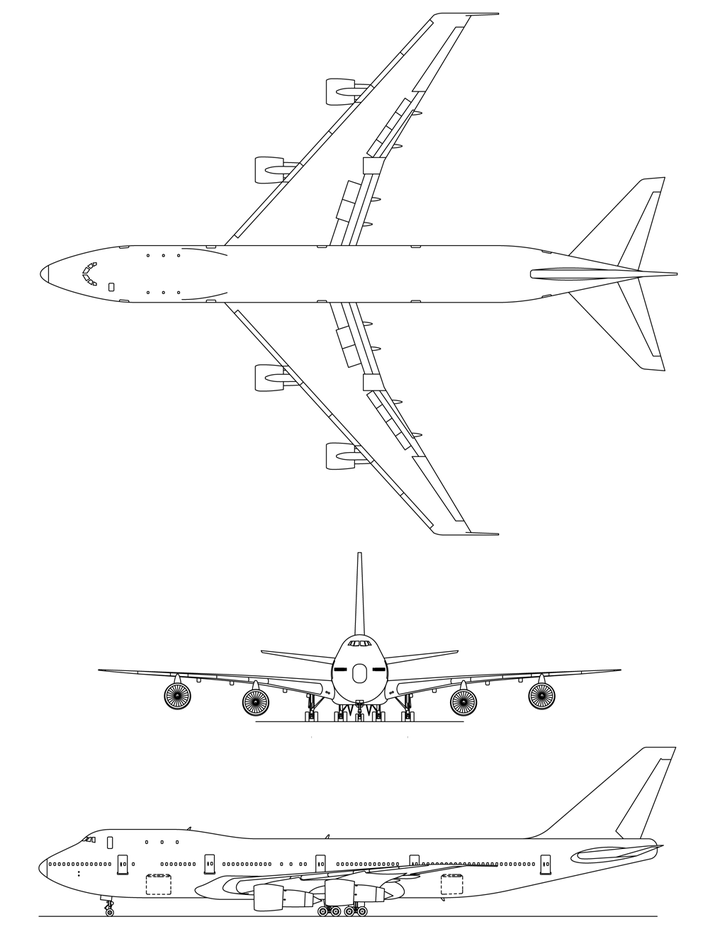

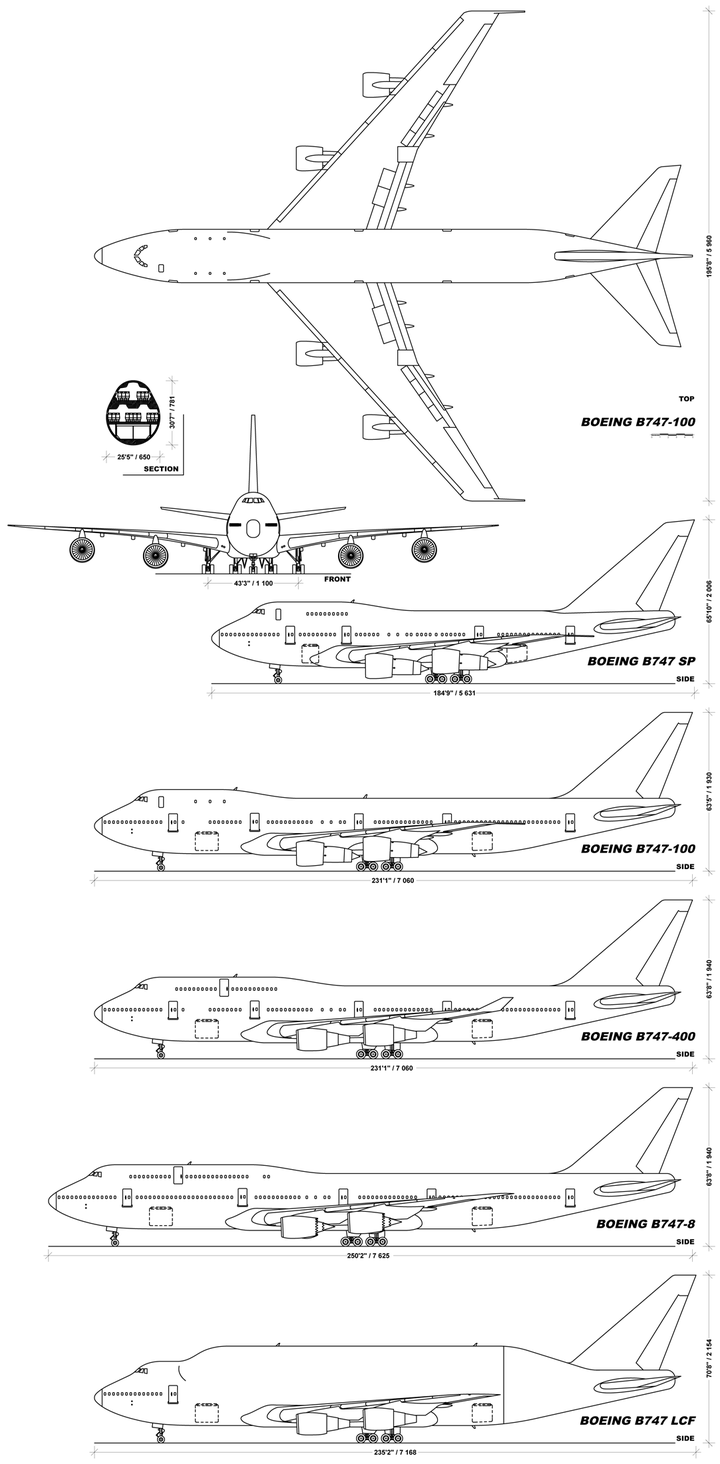

图片题注:3-view drawing of the Boeing 747-100 airliner.

图片作者:Julien.scavini derivative work: MLWatts-This file was derived from:Boeing 747 family v1.0.png

参考译文:波音747-100客机的三视图。

波音747是一款双层、宽体、双通道、四发动机的飞机,其机翼后掠角为37.5度,此角度是为了提高巡航速度之用[27],最佳巡航速度为0.84-0.88马赫(视型号而定),且能够停泊在飞机棚[98]。如果747客舱主层的经济舱座位以3-4-3和头等舱1-2-1的排列,上层以2-2排列方式,747的载客量会超过366人[99]。

波音747的驾驶舱位于上层甲板,驾驶舱后面的空间可以用作客舱或机员休息室,货机型号有可掀起的机鼻舱门[27]。

The “stretched upper deck” became available as an alternative on the 747-100B variant and later as standard beginning on the 747-300. The upper deck was stretched more on the 747-8. The 747 cockpit roof section also has an escape hatch from which crew can exit during the events of an emergency if they cannot do so through the cabin.

参考译文:”伸展式上层甲板”在747-100B版本中作为替代方案出现,后来从747-300开始成为标准配置。上层甲板在747-8上被进一步伸展。747驾驶舱顶部还有一个逃生舱口,如果机组人员无法通过客舱逃生,可以在紧急情况下从此处撤离。

图片题注:Landing gear of a Lufthansa Boeing 747-400

图片来源信息:Photo taken by Michael Krahe, Summer 2002. Licensed under the GFDL.

参考译文:一架汉莎航空波音747-400飞机的起落架

747的最大起飞重量由73万5千磅(334,000千克,-100型)至97万磅(439,985千克,-8型)不等,航程由5,300海里(6,100英里、9,800千米,-100型)至8,000海里(9,210英里、14,815千米,-8I型)不等[100][101]。

因此波音747拥有4套液压系统、多重结构备用装置、18个机轮以支撑如此笨重的飞机,当机轮爆胎时,也能确保飞机可以顺利滑行;而747拥有多组机轮是为了确保当降落时两组坏了,余下的都能够支撑整架飞机[102];而分离式控制面板及精密的三槽式襟翼能够降低降落速度,以确保跑道有足够长度去容纳飞机,减少飞机滑行距离[103]。早期747型号能够在发动机与机身之间、在机翼下增加第五个吊舱以容纳一个不会运作的发动机,用作运送后备发动机[104][105]

The 747’s maximum takeoff weight ranges from 735,000 pounds (333 t) for the -100 to 970,000 pounds (440 t) for the -8. Its range has increased from 5,300 nautical miles (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) on the -100 to 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) on the -8I.[121][122]

参考译文:747的最大起飞重量范围从-100型的735,000磅(333吨)到-8型的970,000磅(440吨)。其航程已从-100型的5,300海里(9,800公里;6,100英里)增加到-8I型的8,000海里(15,000公里;9,200英里)。[121][122]

维基百科的图片说明:Front view showing the triple-slotted trailing edge flaps

图片作者:Adrian Pingstone

参考译文:前视图显示三开槽后缘襟翼

图片题注:Air New Zealand Boeing 747-400 (ZK-SUH) arrives London Heathrow, England. The triple-slotted trailing edge flaps are well displayed.

参考译文:新西兰航空公司波音747-400 (ZK-SUH)抵达英国伦敦希思罗机场。三开槽后缘襟翼得到了很好的展示。

The 747 has redundant structures along with four redundant hydraulic systems and four main landing gears each with four wheels; these provide a good spread of support on the ground and safety in case of tire blow-outs. The main gear are redundant so that landing can be performed on two opposing landing gears if the others are not functioning properly.[123] The 747 also has split control surfaces and was designed with sophisticated triple-slotted flaps that minimize landing speeds and allow the 747 to use standard-length runways.[124]

参考译文:747飞机具有冗余结构,以及四个冗余液压系统和四个主起落架,每个起落架上有四个轮子;这些设计在地面上提供了良好的支撑,并在轮胎爆裂时保证了安全。主起落架也是冗余的,因此如果其他起落架无法正常工作,可以在两个相对的起落架上进行着陆。[123] 747还具有分裂式控制面,并采用复杂的三槽襟翼设计,以最小化着陆速度并允许747使用标准长度的跑道。[124]

For transportation of spare engines, the 747 can accommodate a non-functioning fifth-pod engine under the aircraft’s port wing between the inner functioning engine and the fuselage.[125][126] The fifth engine mount point is also used by Virgin Orbit‘s LauncherOne program to carry an orbital-class rocket to cruise altitude where it is deployed.[127][128]

参考译文:对于备用引擎的运输,747可以在飞机的左机翼下方容纳一个不工作的第五个引擎,位于内部工作引擎和机身之间。[125][126] 第五个引擎安装点还被维珍轨道公司的LauncherOne计划用于携带轨道级火箭到达巡航高度,然后进行部署。[127][128]

3. 子型号 | Variants

波音747-100是747的原始型号,在1966年开发,747-200在1968年接到订单后便进行开发,而747-300和747-400分别在1980年和1985年开发,而最新型号747-8是在2005年宣布开发。每款747都有其衍生型号。在早期747型号中有许多都是同期生产的。

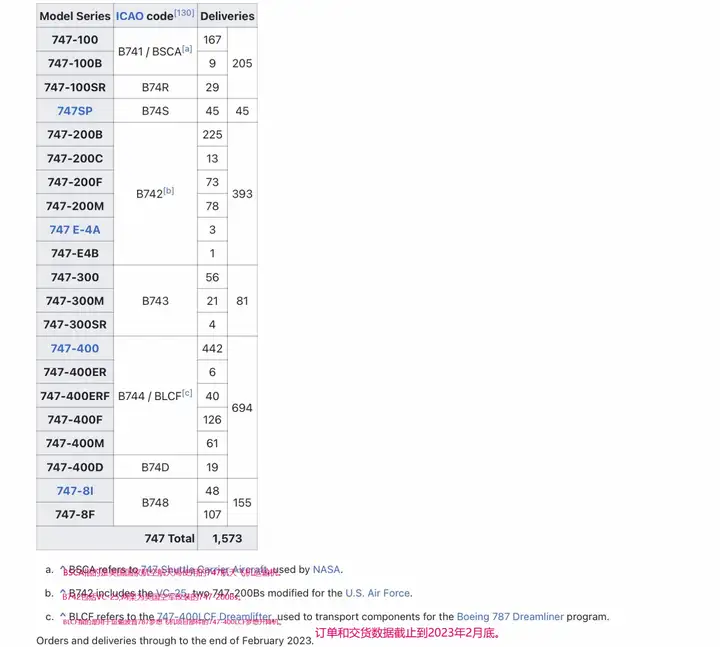

The International Civil Aviation Organization(ICAO) classifies variants using a shortened code formed by combining the model number and the variant designator (e.g. “B741” for all -100 models).[130]

参考译文:国际民用航空组织(ICAO)使用由型号和变体指示器组合而成的缩国际民用航空组织(ICAO)使用由型号和变体指示器组合而成的缩写代码对变体进行分类(例如,所有-100型号的“B741”)。[130]

3.1 747-100

维基百科的图片说明:The original 747-100 has a short upper deck with three windows per side;Pan Amintroduced it on January 22, 1970

图片作者:Aldo Bidini-点击这里访问原图链接

参考译文:最初的747-100型上层甲板较短,每侧有3个窗口;泛美航空公司于1970年1月22日推出

维基百科的图片说明:泛美航空为波音747的启动用户

图片作者:Arthur Tress

The first 747-100s were built with six upper deck windows (three per side) to accommodate upstairs lounge areas. Later, as airlines began to use the upper deck for premium passenger seating instead of lounge space, Boeing offered an upper deck with ten windows on either side as an option. Some early -100s were retrofitted with the new configuration.[131] The -100 was equipped with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-3A engines. No freighter version of this model was developed, but many 747-100s were converted into freighters as 747-100(SF).[132] The first 747-100(SF) was delivered to Flying Tiger Line in 1974.[133]A total of 168 747-100s were built; 167 were delivered to customers, while Boeing kept the prototype, City of Everett.[134] In 1972, its unit cost was US$24M[135] (167.9M today).

参考译文:最初的747-100型号飞机在上层甲板设有六个窗户(每侧三个),以容纳楼上的休息区。最初的747-100型飞机有六个上层甲板窗户(每侧三个),以容纳楼上的休息区。后来,随着航空公司开始将上层甲板用于高级乘客座位而不是休息空间,波音提供了一种每侧有十个窗户的上层甲板作为选项。一些早期的-100型飞机被改装成新的配置。[131] -100型飞机配备了普惠JT9D-3A发动机。没有开发这种型号的货机版本,但许多747-100型飞机被改装成货机,即747-100(SF)。[132]第一架747-100(SF)于1974年交付给飞虎航空公司。[133]共生产了168架747-100型飞机;其中167架交付给客户,而波音保留了原型机埃弗雷特城。[134]1972年,其单位成本为2400万美元[135](相当于今天的1.679亿美元)。

3.2 747SR

维基百科的图片说明:日本航空旗下的747-146B/SR/SUD(JA8170,另一架为JA8176)

图片作者:japjap

维基百科的图片说明:全日本空输的747SR(使用通用电气CF6-45A2引擎;当时全日空以达·芬奇设计的直升机为标志)

图片作者:John Wheatley

Responding to requests from Japanese airlines for a high-capacity aircraft to serve domestic routes between major cities, Boeing developed the 747SR as a short-range version of the 747-100 with lower fuel capacity and greater payload capability. With increased economy class seating, up to 498 passengers could be carried in early versions and up to 550 in later models.[79]

参考译文:为满足日本航空公司在主要城市之间国内航线的大容量飞机需求,波音公司为满足日本航空公司在主要城市之间国内航线的大容量飞机需求,波音公司开发了747SR,这是747-100的短程版本,具有较低的燃油容量和更大的载重能力。随着经济舱座位的增加,早期版本最多可搭载498名乘客,后期版本最多可搭载550名乘客。[79]

The 747SR had an economic design life objective of 52,000 flights during 20 years of operation, compared to 24,600 flights in 20 years for the standard 747.[136] The initial 747SR model, the -100SR, had a strengthened body structure and landing gear to accommodate the added stress accumulated from a greater number of takeoffs and landings.[137] Extra structural support was built into the wings, fuselage, and the landing gear along with a 20% reduction in fuel capacity.[138]

参考译文:747SR的经济设计使用寿命目标为20年内飞行52,000次,而标准747为20年内飞行24,600次。[136] 最初的747SR型号,即-100SR,其机身结构和起落架经过加强,以适应因更多起飞和降落而产生的额外应力。[137] 机翼、机身和起落架上都增加了额外的结构支撑,同时燃油容量减少了20%。[138]

维基百科的图片说明:One of the two 747-100BSR with the stretched upper deck (SUD) made for JAL

参考译文:这架为日本航空公司制造的两架747-100BSR之一,采用了拉伸上层甲板(SUD)设计。图片题注:Japan Airlines had some of their late-build B747-100’s built with the -300 series stretched upper deck for use on high density domestic services. KLM were the only other airline to have some of their B747-200’s modified to ‘SUD’ standard.

图片作者:Ken Fielding

参考译文:日本航空公司的一些后期建造的B747-100型飞机采用了-300系列的拉伸上层甲板,用于高密度国内服务。荷兰皇家航空公司是唯一一家将其部分B747-200型飞机改装为“SUD”标准的航空公司。

波音公司按日本航空公司的要求而在747-100的基础上研发一款短程用客机747-100SR(Short Range),增强了机体结构以抵受频密的起降次数,减少了燃料缸并增加载客量至498人,后期更可高达550人(全经济舱)[72]。由于747-100SR的燃油负载量少了20%,因此多出的空量能够强化机翼、机身和机轮结构[112]。747-100SR在1973年10月7日投入服务[36],至1975年共生产7架。这七架747SR的最大起飞重量为520,000英磅(240,000千克),发动机为推力减至43,000英磅力(190,000牛顿)的JT9D-7A,全部交付给日本航空。

1978年,波音在747-100SR的基础上推出结构加强、最大起飞重量更大的747-100BSR,该型号于1978年11月3日首飞,首两架同年12月交付给全日本空输,全日空也成为-100BSR的主要用户,自1979年1月25日至2006年3月10日共计运营17架该型机[113],且全部使用CF6-45A2发动机,而日航也曾运营3架装有JT9D发动机的-100BSR。后来波音公司更研制出747-300SR和747-400D,皆是日本国内线专用的特殊规格机种[114]。

ANA operated this variant on domestic Japanese routes with 455 or 456 seats until retiring its last aircraft in March 2006.[141]

参考译文:全日空航空公司运营这种变种的国内日本航线,有455或456个座位,直到2006年3月退役其最后一架。

波音公司共交付了两架747-100SUD(上层客舱增长并增加了一对逃生门,后来747-300/400标准版均沿用了该设计)来给日本航空以容纳更多乘客[115][116]。日本航空作运营的747-100SR/SUD的载客量高达563人,最后一架在2006年第三季退役。而全日空曾运营不少747SR,载客量为455至456人,最后一架在2006年3月10日退役[117]。日本航空和日线航空曾运营747-300SR,主要负责国内线和部分亚洲航线,已于2009年7月退役。一架747-100SR(原日航JA8117)由美国NASA改装为可背负航天飞机飞行的SCA(航天飞机运输机)。

3.3 747-100B

图片题注:Iran Air Boeing 747-100B

图片作者:Chris Lofting

参考译文:伊朗航空的波音747-100B

The 747-100B model was developed from the -100SR, using its stronger airframe and landing gear design. The type had an increased fuel capacity of 48,070 US gal (182,000 L), allowing for a 5,000-nautical-mile (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) range with a typical 452-passenger payload, and an increased MTOW of 750,000 lb (340 t) was offered. The first -100B order, one aircraft for Iran Air, was announced on June 1, 1978. This version first flew on June 20, 1979, received FAA certification on August 1, 1979, and was delivered the next day.[144]

参考译文:波音747-1波音747-100B型飞机是由-100SR型号发展而来,采用了更强大的机身和起落架设计。该型号的燃油容量增加了48,070美国加仑(182,000升),使得在典型的452名乘客载荷下,航程可达5,000海里(9,300公里;5,800英里),最大起飞重量增加到750,000磅(340吨)。1978年6月1日,首架-100B订单(一架供伊朗航空使用)宣布。这一版本于1979年6月20日首次飞行,于1979年8月1日获得联邦航空管理局认证,并于次日交付。[144]

Nine -100Bs were built, one for Iran Air and eight for Saudi Arabian Airlines.[145][146] Unlike the original -100, the -100B was offered with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7A, CF6-50, or Rolls-Royce RB211-524 engines. However, only RB211-524 (Saudia) and JT9D-7A (Iran Air) engines were ordered.[147] The last 747-100B, EP-IAM was retired by Iran Air in 2014, the last commercial operator of the 747-100 and -100B.[148]

参考译文:共生产了九架-100B,一架供伊朗航空使用,八架供沙特阿拉伯航空公司使用。[145][146]与最初的-100不同,-100B提供普惠JT9D-7A、CF6-50或劳斯莱斯RB211-524发动机。然而,只有RB211-524(沙特阿拉伯)和JT9D-7A(伊朗航空)发动机被订购。[147]最后一架747-100B,EP-IAM于2014年由伊朗航空退役,是最后一家使用747-100和-100B的商业运营商。[148]

3.4 747SP

Main article: Boeing 747SP

图片题注:Boeing 747SP of Korean Air Lines at Basle Airport

图片作者:Eduard Marmet

参考译文:大韩航空的波音747SP在巴塞尔机场

The development of the 747SP stemmed from a joint request between Pan American World Airways and Iran Air, who were looking for a high-capacity airliner with enough range to cover Pan Am’s New York–Middle Eastern routes and Iran Air’s planned Tehran–New York route. The Tehran–New York route, when launched, was the longest non-stop commercial flight in the world. The 747SP is 48 feet 4 inches (14.73 m) shorter than the 747-100. Fuselage sections were eliminated fore and aft of the wing, and the center section of the fuselage was redesigned to fit mating fuselage sections. The SP’s flaps used a simplified single-slotted configuration.[149][150]

参考译文:747SP的发展源于泛美世界航空公司和伊朗航空公司的共同需求,他们希望找到一种高容量的客机,其航程足以覆盖泛美的纽约至中东航线以及伊朗航空计划的德黑兰至纽约航线。当这条航线启动时,它是世界上最长的直飞商业航班。747SP比747-100短48英尺4英寸(14.73米)。机身前后部分被取消,机身中部被重新设计以适应匹配的机身部分。SP的襟翼采用了简化的单槽配置。[149][150]

The 747SP, compared to earlier variants, had a tapering of the aft upper fuselage into the empennage, a double-hinged rudder, and longer vertical and horizontal stabilizers.[151] Power was provided by Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7(A/F/J/FW) or Rolls-Royce RB211-524 engines.[152]

参考译文:与早期版本相比,747SP的后上机身逐渐变细到尾翼,双铰接方向舵,以及更长的垂直和水平稳定器。[151]动力由普惠JT9D-7(A/F/J/FW)或劳斯莱斯RB211-524发动机提供。[152]

图片题注:An Air Namibia Boeing 747SP-44 at Frankfurt Airport (FRA/EDDF)

图片作者:Torsten Maiwald

参考译文:一架纳米比亚航空公司波音747SP-44在法兰克福机场(FRA/EDDF)

The 747SP was granted a type certificate on February 4, 1976, and entered service with launch customers Pan Am and Iran Air that same year.[150] The aircraft was chosen by airlines wishing to serve major airports with short runways.[153] A total of 45 747SPs were built,[134] with the 44th 747SP delivered on August 30, 1982. In 1987, Boeing re-opened the 747SP production line after five years to build one last 747SP for an order by the United Arab Emirates government.[150] In addition to airline use, one 747SP was modified for the NASA/German Aerospace Center SOFIA experiment.[154] Iran Air is the last civil operator of the type; its final 747-SP (EP-IAC) was to be retired in June 2016.[155][156]

参考译文:747SP于1976年2月4日获得型号证书,并于同年与启动客户泛美航空公司和伊朗航空公司一起投入使用。[150] 航空公司希望为主要机场提供服务,这些机场跑道较短,因此选择了这种飞机。[153] 共生产了45架747SP,[134] 第44架747SP于1982年8月30日交付。1987年,波音公司在五年后重新开放了747SP生产线,为阿拉伯联合酋长国政府的一项订单建造了最后一架747SP。[150] 除了航空公司的使用外,还有一架747SP被修改用于美国国家航空航天局/德国航空航天中心的SOFIA实验。[154] Iran Air是该型号的最后一个民用运营商;其最后一架747-SP(EP-IAC)计划于2016年6月退役。[155][156]

3.5 747-200

图片题注:Most 747-200s had ten windows per side on the upper deck

图片作者:Aldo Bidini

参考译文:大多数747-200型飞机在上层甲板每侧有10个窗户。

维基百科的图片说明:1976年,北欧航空一架波音747-283B在斯德哥尔摩阿兰达机场,注意其上层窗口仍为每边3个

图片作者:原上传者为英语维基百科的Brorsson

维基百科的图片说明:北欧航空的波音747-200BM客货混合机,图中飞机为波音公司制造的第500架747

图片作者:Jon Proctor

While the 747-100 powered by Pratt & Whitney JT9D-3A engines offered enough payload and range for medium-haul operations, it was marginal for long-haul route sectors. The demand for longer range aircraft with increased payload quickly led to the improved -200, which featured more powerful engines, increased MTOW, and greater range than the -100. A few early -200s retained the three-window configuration of the -100 on the upper deck, but most were built with a ten-window configuration on each side.[157] The 747-200 was produced in passenger (-200B), freighter (-200F), convertible (-200C), and combi (-200M) versions.[158]

参考译文:虽然由普惠JT9D-3A发动机驱动的747-100型飞机在中程运营中提供了足够的载荷和航程,但对于长途航线来说却有些勉强。对具有更长航程和更大载荷的飞机的需求迅速导致了改进的-200型飞机的出现,它配备了更强大的发动机,增加了最大起飞重量(MTOW),并且比-100型飞机具有更大的航程。一些早期的-200型飞机保留了-100型飞机上层甲板的三窗配置,但大多数都采用了每侧十窗的配置。[157] 747-200型飞机有客运(-200B)、货运(-200F)、可转换(-200C)和组合(-200M)版本。[158]

The 747-200B was the basic passenger version, with increased fuel capacity and more powerful engines; it entered service in February 1971.[83] In its first three years of production, the -200 was equipped with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7 engines (initially the only engine available). Range with a full passenger load started at over 5,000 nmi (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) and increased to 6,000 nmi (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) with later engines. Most -200Bs had an internally stretched upper deck, allowing for up to 16 passenger seats.[159] The freighter model, the 747-200F, had a hinged nose cargo door and could be fitted with an optional side cargo door,[83] and had a capacity of 105 tons (95.3 tonnes) and an MTOW of up to 833,000 pounds (378 t). It entered service in 1972 with Lufthansa.[160] The convertible version, the 747-200C, could be converted between a passenger and a freighter or used in mixed configurations,[79] and featured removable seats and a nose cargo door.[83] The -200C could also be outfitted with an optional side cargo door on the main deck.[161]

参考译文:747-200B是基本客运版本,具有更大的燃油容量和更强大的发动机;它于1971年2月投入使用。[83]在最初的三年生产中,-200配备了普惠JT9D-7发动机(最初是唯一可用的发动机)。满载乘客时,航程从5,000海里(9,300公里;5,800英里)开始,后来的发动机增加到6,000海里(11,000公里;6,900英里)。大多数-200Bs有一个内部延伸的上层甲板,最多可容纳16个乘客座位。[159]货运型号747-200F有一个铰链式鼻子货舱门,并可以安装可选的侧货舱门,[83]容量为105吨(95.3吨),最大起飞重量可达833,000磅(378吨)。它于1972年与德国汉莎航空公司一起投入使用。[160]转换型747-200C可以在客运和货运之间转换或用于混合配置,[79]并具有可拆卸座椅和鼻子货舱门。[83] -200C还可以在主甲板上安装可选的侧货舱门。[161]

维基百科的图片说明:香港华民航空的波音747-200F

图片作者:Torsten Maiwald

维基百科的图片说明:伊朗航空的波音747-200C;该机属于后期型747-200,故HF天线已移位

图片作者:N509FZ

The combi aircraft model, the 747-200M (originally designated 747-200BC), could carry freight in the rear section of the main deck via a side cargo door. A removable partition on the main deck separated the cargo area at the rear from the passengers at the front. The -200M could carry up to 238 passengers in a three-class configuration with cargo carried on the main deck. The model was also known as the 747-200 Combi.[83] As on the -100, a stretched upper deck (SUD) modification was later offered. A total of 10 747-200s operated by KLM were converted.[83] Union de Transports Aériens (UTA) also had two aircraft converted.[162][163]

参考译文:747-200M(最初被指定为747-200BC)是一款组合飞机模型,可以通过侧货舱门在主甲板后部携带货物。主甲板上的可移动隔板将后部的货物区域与前部的乘客分开。在三舱配置下,747-200M最多可以搭载238名乘客,并在主甲板上携带货物。该型号也被称为747-200 Combi。[83] 与-100一样,后来还提供了延长的上层甲板(SUD)改装。荷兰皇家航空公司运营的10架747-200中,有10架进行了改装。[83] 法国航空运输联盟(UTA)也有两架飞机进行了改装。[162][163]

After launching the -200 with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7 engines, on August 1, 1972, Boeing announced that it had reached an agreement with General Electric to certify the 747 with CF6-50 series engines to increase the aircraft’s market potential. Rolls-Royce followed 747 engine production with a launch order from British Airways for four aircraft. The option of RB211-524B engines was announced on June 17, 1975.[147]The -200 was the first 747 to provide a choice of powerplant from the three major engine manufacturers.[164] In 1976, its unit cost was US$39M (200.6M today).

参考译文:在1972年8月1日推出装有普惠JT9D-7发动机的-200型飞机后,波音公司宣布与通用电气达成协议,对747进行CF6-50系列发动机认证,以增加该飞机的市场潜力。劳斯莱斯紧随其后,接到英国航空公司的四架飞机订单。1975年6月17日宣布了RB211-524B发动机选项。[147] -200型是第一款提供三家主要发动机制造商动力装置选择的747飞机。[164] 1976年,其单位成本为3900万美元(相当于今天的2.006亿美元)。

A total of 393 of the 747-200 versions had been built when production ended in 1991.[165] Of these, 225 were -200B, 73 were -200F, 13 were -200C, 78 were -200M, and 4 were military.[166] Iran Air retired the last passenger 747-200 in May 2016, 36 years after it was delivered.[167]As of July 2019, five 747-200s remain in service as freighters.[168]

参考译文:在1991年停产时,共生产了747-200型飞机393架。其中,225架是-200B型,73架是-200F型,13架是-200C型,78架是-200M型,还有4架是军用型。伊朗航空公司于2016年5月退役了最后一架747-200客机,距离该机交付已经过去了36年。截至2019年7月,仍有5架747-200型飞机作为货机继续服役。

3.6 747-300

维基百科的图片说明:新加坡航空的波音747-300BIG TOP客机

图片作者:Communi core by S.Fujioka

维基百科的图片说明:日线航空的747-346SR(后易手俄罗斯洲际航空)

图片作者:Shacho0822

The 747-300 features a 23-foot-4-inch-longer (7.11 m) upper deck than the -200.[84] The stretched upper deck (SUD) has two emergency exit doors and is the most visible difference between the -300 and previous models.[169] After being made standard on the 747-300, the SUD was offered as a retrofit, and as an option to earlier variants still in-production. An example for a retrofit were two UTA -200 Combis being converted in 1986, and an example for the option were two brand-new JAL -100 aircraft (designated -100BSR SUD), the first of which was delivered on March 24, 1986.[82]: 68, 92

参考译文:波音747-300型飞机的上层甲板比747-200型长23英尺4英寸(7.11米)。[84] 延长的上层甲板(SUD)有两个紧急出口门,这是747-300型与之前型号最明显的区别。[169] 在747-300型上成为标准配置后,SUD作为改装选项提供,也可以用于仍在生产的早期版本。1986年,两架UTA-200 Combis进行了改装,这是一个改装的例子;还有两个全新的日航-100飞机(被指定为-100BSR SUD),第一架于1986年3月24日交付,这是选择SUD选项的例子。[82]: 68, 92

The 747-300 introduced a new straight stairway to the upper deck, instead of a spiral staircase on earlier variants, which creates room above and below for more seats.[79] Minor aerodynamic changes allowed the -300’s cruise speed to reach Mach 0.85 compared with Mach 0.84 on the -200 and -100 models, while retaining the same takeoff weight.[84] The -300 could be equipped with the same Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce powerplants as on the -200, as well as updated General Electric CF6-80C2B1 engines.[79]

参考译文:波音747-300型飞机引入了一个新的直波音747-300型飞机引入了一个新的直梯到上层甲板,而不是早期变种的螺旋楼梯,这在上下创造了更多的座位空间。[79]轻微的空气动力学变化使得-300型的巡航速度达到了马赫0.85,而-200和-100型号的巡航速度为马赫0.84,同时保持了相同的起飞重量。[84] -300型可以使用与-200型相同的普惠和劳斯莱斯动力装置,以及更新的通用电气CF6-80C2B1发动机。[79]

Swissair placed the first order for the 747-300 on June 11, 1980.[170] The variant revived the 747-300 designation, which had been previously used on a design study that did not reach production. The 747-300 first flew on October 5, 1982, and the type’s first delivery went to Swissair on March 23, 1983.[37] In 1982, its unit cost was US$83M (251.7M today). Besides the passenger model, two other versions (-300M, -300SR) were produced.

参考译文:瑞士航空公司于1980年6月11日首次订购了747-300型飞机。[170]这种变体重新启用了747-300的命名,此前该名称曾用于一项未投产的设计研究。747-300于1982年10月5日首次飞行,并于1983年3月23日交付给瑞士航空公司。[37] 1982年,其单位成本为8300万美元(相当于今天的2.517亿美元)。除了客运型号外,还生产了另外两种型号(-300M和-300SR)。

维基百科的图片说明:A 747-300, with its stretched upper deck, flying-by the Matterhorn. Swissair took the first

图片作者:de:Georg Gerster, Swissair

参考译文:一架747-300,带着它加长的上层甲板,飞过马特洪峰。瑞士航空公司是第一个

The 747-300M features cargo capacity on the rear portion of the main deck, similar to the -200M, but with the stretched upper deck it can carry more passengers.[152][171] The 747-300SR, a short range, high-capacity domestic model, was produced for Japanese markets with a maximum seating for 584.[172] No production freighter version of the 747-300 was built, but Boeing began modifications of used passenger -300 models into freighters in 2000.[173]

参考译文:747-300M在主甲板的后部具有类似-200M的货运能力,但由于延长了上层甲板,它可以容纳更多的乘客。[152][171] 747-300SR是一种短程、高容量的国内型号,专为日本市场生产,最多可容纳584名乘客。[172]没有生产过747-300型的货运飞机,但波音公司在2000年开始将使用的-300型客机改装成货机。[173]

A total of 81 747-300 series aircraft were delivered, 56 for passenger use, 21 -300M and 4 -300SR versions.[174] In 1985, just two years after the -300 entered service, the type was superseded by the announcement of the more advanced 747-400.[175] The last 747-300 was delivered in September 1990 to Sabena.[79][176] While some -300 customers continued operating the type, several large carriers replaced their 747-300s with 747-400s. Air France, Air India, Pakistan International Airlines, and Qantas were some of the last major carriers to operate the 747-300.

参考译文:共有81架747-300系列飞机交付,其中56架用于客运,21架为-300M版本,4架为-300SR版本。[174] 1985年,即-300开始服役仅两年后,波音公司宣布了更先进的747-400型飞机,取代了747-300。[175] 最后一架747-300于1990年9月交付给Sabena航空公司。[79][176] 尽管一些747-300客户继续运营这种型号,但几家大型航空公司将其747-300替换为747-400。法国航空、印度航空、巴基斯坦国际航空公司和澳航是最后几家运营747-300的大型航空公司。

On December 29, 2008, Qantas flew its last scheduled 747-300 service, operating from Melbourne to Los Angeles via Auckland.[177] In July 2015, Pakistan International Airlines retired their final 747-300 after 30 years of service.[178] As of July 2019, only two 747-300s remain in commercial service, with Mahan Air (1) and TransAVIAexport Airlines (1).[168]

参考译文:2008年12月29日,澳航在其最后一趟计划中的747-300服务中从墨尔本飞往洛杉矶经奥克兰。[177] 2015年7月,巴基斯坦国际航空公司在服役30年后退役了其最后一架747-300。[178] 截至2019年7月,只有两架747-300仍在商业运营中,分别是Mahan Air(1架)和TransAVIAexport Airlines(1架)。[168]

3.7 747-400

Main article: Boeing 747-400

主条目:波音747-400

维基百科的图片说明:The improved 747-400, featuring canted winglets, entered service in February 1989 with Northwest Airlines

图片作者:Cory W. Watts from Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America

参考译文:改进型747-400以倾斜小翼为特色,于1989年2月在西北航空公司投入使用

图片题注:British Airways Boeing 747-400 (G-BNLE) takes off from London Heathrow Airport, England. The undercarriages are retracting.

图片作者:Adrian Pingstone

参考译文:英国航空公司的波音747-400(G-BNLE)从英格兰伦敦希思罗机场起飞。起落架正在收回。

The 747-400 is an improved model with increased range. It has wingtip extensions of 6 ft (1.8 m) and winglets of 6 ft (1.8 m), which improve the type’s fuel efficiency by four percent compared to previous 747 versions.[179] The 747-400 introduced a new glass cockpit designed for a flight crew of two instead of three, with a reduction in the number of dials, gauges and knobs from 971 to 365 through the use of electronics. The type also features tail fuel tanks, revised engines, and a new interior. The longer range has been used by some airlines to bypass traditional fuel stops, such as Anchorage.[180]

参考译文:波音747-400是一款改进型飞机,具有更长的航程。它的翼尖延伸了6英尺(1.8米),机翼尖部有6英尺(1.8米)的翼尖小翼,与之前的747型号相比,这种设计将燃油效率提高了4%。[179] 747-400引入了一个全新的玻璃驾驶舱,设计为两名乘务员而不是三名,通过使用电子设备将仪表、仪表盘和旋钮的数量从971个减少到365个。这款飞机还配备了尾置油箱、改进的发动机和全新的内饰。一些航空公司利用其更长的航程来绕过传统的燃油补给站,如安克雷奇。[180]

A 747-400 loaded with 126,000 pounds (57,000 kg) of fuel flying 3,500 miles (3,000 nmi; 5,600 km) consumes an average of 5 US gallons per mile (12 L/km).[181][182] Powerplants include the Pratt & Whitney PW4062, General Electric CF6-80C2, and Rolls-Royce RB211-524.[183] As a result of the Boeing 767 development overlapping with the 747-400’s development, both aircraft can use the same three powerplants and are even interchangeable between the two aircraft models.[184]

参考译文:一架满载126,000磅(57,000公斤)燃油、飞行3,500英里(3,000海里;5,600公里)的747-400平均消耗5加仑/英里(12升/公里)的燃油。[181][182] 动力装置包括普惠PW4062、通用电气CF6-80C2和劳斯莱斯RB211-524。[183] 由于波音767的开发与747-400的开发重叠,这两种飞机都可以使用相同的三种动力装置,甚至可以在两种飞机型号之间互换。[184]

The -400 was offered in passenger (-400), freighter (-400F), combi (-400M), domestic (-400D), extended range passenger (-400ER), and extended range freighter (-400ERF) versions. Passenger versions retain the same upper deck as the -300, while the freighter version does not have an extended upper deck.[185] The 747-400D was built for short-range operations with maximum seating for 624. Winglets were not included, but they can be retrofitted.[186][187] Cruising speed is up to Mach 0.855 on different versions of the 747-400.[183]

参考译文:747-400提供乘客(-400)、货运(-400F)、组合(-400M)、国内(-400D)、延长航程乘客(-400ER)和延长航程货运(-400ERF)版本。乘客版本保留了与-300相同的上层甲板,而货运版本没有延长的上层甲板。[185] 747-400D是为短程运营而建造的,最多可容纳624人。机翼尖没有被包括在内,但可以改装。[186][187] 不同版本的747-400巡航速度高达0.855马赫。[183]

The passenger version first entered service in February 1989 with launch customer Northwest Airlines on the Minneapolis to Phoenix route.[188] The combi version entered service in September 1989 with KLM, while the freighter version entered service in November 1993 with Cargolux. The 747-400ERF entered service with Air France in October 2002, while the 747-400ER entered service with Qantas,[189] its sole customer, in November 2002. In January 2004, Boeing and Cathay Pacific launched the Boeing 747-400 Special Freighter program,[190] later referred to as the Boeing Converted Freighter (BCF), to modify passenger 747-400s for cargo use. The first 747-400BCF was redelivered in December 2005.[191]

参考译文:1989年2月,波音747-400客机版本首次投入使用,首个客户是美国西北航空公司,用于明尼阿波利斯至菲尼克斯航线。[188] 1989年9月,KLM航空公司开始使用747-400货机版本,而货运版本于1993年11月与Cargolux航空公司一起投入使用。747-400ERF于2002年10月由法国航空公司投入使用,而747-400ER于2002年11月由其唯一客户澳洲航空投入使用。2004年1月,波音公司和国泰航空启动了波音747-400特殊货运项目(后来被称为波音改装货机),以将乘客747-400改装为货运用途。第一架747-400BCF于2005年12月重新交付。[191]

In March 2007, Boeing announced that it had no plans to produce further passenger versions of the -400.[192] However, orders for 36 -400F and -400ERF freighters were already in place at the time of the announcement.[192] The last passenger version of the 747-400 was delivered in April 2005 to China Airlines. Some of the last built 747-400s were delivered with Dreamliner livery along with the modern Signature interior from the Boeing 777. A total of 694 of the 747-400 series aircraft were delivered.[134] At various times, the largest 747-400 operator has included Singapore Airlines,[193] Japan Airlines,[193] and British Airways.[194][195] As of July 2019, 331 Boeing 747-400s were in service;[168]there were only 10 Boeing 747-400s in passenger service as of September 2021.[196]

参考译文:2007年3月,波音公司宣布其没有计划进一步生产747-400的客运版本。[192]然而,当时已有36架-400F和-400ERF货机的订单。[192]最后一架747-400的客运版本于2005年4月交付给中华航空公司。一些最后生产的747-400配备了梦幻客机涂装和来自波音777的现代Signature内饰。747-400系列飞机共交付了694架。[134]新加坡航空公司、日本航空公司和英国航空公司等都曾是最大的747-400运营商。[193][195]截至2019年7月,有331架波音747-400在服役;[168]截至2021年9月,只有10架波音747-400用于客运服务。[196]

3.8 747 LCF Dreamlifter

Main article: Boeing Dreamlifter

主条目:波音Dreamlifter

维基百科的图片说明:波音747 LCF

图片作者:Nathan Coats from Seattle, WA, United States of America

波音747梦幻货机[147](Dreamlifter,原称Large Cargo Freighter或LCF[148])是一款以747-400和747SP为基础,由波音公司设计,长荣航太科技将747-400与747SP组合为747 LCF,用来运送波音787的机身组件[149]。747 LCF在2006年9月9日首飞[150],该飞机的适航证书只是供飞机运货之用,不设客运[151],截至2010年前已经改装了四架[148]。

3.9 747-8

Main article: Boeing 747-8

主条目:波音747-8

维基百科的图片说明:汉莎航空的波音747-8I,可见舷窗已经由747-400的方形改为与777同样的圆形

图片作者:Paul Nelhams from Shannon, Ireland

维基百科的图片说明:英国航空的波音747-8F(由亚特拉斯航空旗下子公司Global Supply Systems营运)

图片作者:Milad A380 (talk)

图片题注:置于广州民航职业技术学院花都赤坭校区图书馆的波音747-8结构图

图片作者:橙子木

Boeing announced a new 747 variant, the 747-8, on November 14, 2005. Referred to as the 747 Advanced prior to its launch, the 747-8 uses similar General Electric GEnx engines and cockpit technology to the 787. The variant is designed to be quieter, more economical, and more environmentally friendly. The 747-8’s fuselage is lengthened from 232 feet (71 m) to 251 feet (77 m),[202]marking the first stretch variant of the aircraft.

参考译文:波音公司在200波音公司在2005年11月14日宣布了一款新的747变种机型,即747-8。在发布之前,这款飞机被称为747先进型,它使用了与787类似的通用电气GEnx发动机和驾驶舱技术。这款变种机型旨在更加安静、经济和环保。747-8的机身长度从232英尺(71米)延长到251英尺(77米),成为该系列飞机的第一个延伸变种。

The 747-8 Freighter, or 747-8F, has 16% more payload capacity than its predecessor, allowing it to carry seven more standard air cargo containers, with a maximum payload capacity 154 tons (140 tonnes) of cargo.[203] As on previous 747 freighters, the 747-8F features a flip up nose-door, a side-door on the main deck, and a side-door on the lower deck (“belly”) to aid loading and unloading. The 747-8F made its maiden flight on February 8, 2010.[204][205] The variant received its amended type certificate jointly from the FAA and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) on August 19, 2011.[206] The -8F was first delivered to Cargolux on October 12, 2011.[207]

参考译文:波音747-8货机(747-8F)的载货能力比其前身增加了16%,使其能够多装载7个标准航空集装箱,最大载货能力为154吨(140公吨)货物。[203] 与之前的747货机一样,747-8F配备了可翻转的机头门、主甲板上的侧门和下甲板(“腹部”)上的侧门,以便于装卸货物。747-8F于2010年2月8日进行了首次试飞。[204][205] 该型号飞机于2011年8月19日获得了美国联邦航空管理局(FAA)和欧洲航空安全局(EASA)联合颁发的修订型证书。[206] 747-8F于2011年10月12日首次交付给Cargolux航空公司。[207]

The passenger version, named 747-8 Intercontinental or 747-8I, is designed to carry up to 467 passengers in a 3-class configuration and fly more than 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at Mach 0.855. As a derivative of the already common 747-400, the 747-8I has the economic benefit of similar training and interchangeable parts.[208] The type’s first test flight occurred on March 20, 2011.[209] The 747-8 has surpassed the Airbus A340-600 as the world’s longest airliner, a record it would hold until the 777X, which first flew in 2020. The first -8I was delivered in May 2012 to Lufthansa.[210] The 747-8 has received 155 total orders, including 106 for the -8F and 47 for the -8I as of June 2021.[134] The final 747-8F was delivered to Atlas Air on January 31, 2023.[117]

参考译文:这款名为747-8洲际或747-8I的客运版本,设计最多可搭载467名乘客,采用3舱配置,在0.855马赫速度下飞行超过8000海里(15000公里;9200英里)。作为已经常见的747-400的衍生型号,747-8I具有相似的培训和经济性以及可互换部件的优势。[208]该型号于2011年3月20日进行了首次试飞。[209] 747-8已经超过空客A340-600成为世界上最长的客机,这一纪录一直保持到2020年首飞的波音777X。第一架747-8I于2012年5月交付给德国汉莎航空公司。[210]截至2021年6月,747-8共获得了155个订单,其中包括106架747-8F和47架747-8I。[134]最后一架747-8F于2023年1月31日交付给Atlas Air。[117]

3.10 政府、军事及其它子型号 | Government, military, and other variants

一些747用作国家政府行政专机,包括中国、韩国、土耳其、摩洛哥、埃及、汶莱、科威特、巴林、卡塔尔、沙乌地阿拉伯、阿联、阿曼。

维基百科的图片说明:机尾号码29000的VC-25A,改装自747-200B,自1990年起便成为美国总统的专机

图片作者:SSGT Alex Lloyd, USAF

VC-25:原本是747-200B,由美国空军操作,用来运载美国总统等重量级人物。目前美国空军有两架VC-25A,机尾编号为28000和29000,它们便是著名的空军一号,空军一号是对搭载美国总统的任何美国空军飞机的称呼。虽然飞机改装自747-200B,但机上有很多改良技术是都属于波音747-400的,例如驾驶舱和发动机。部份飞机在艾佛瑞特生产完成后,便飞往威奇托(辽观注:波音军事公司所在地),进行最后组装,而不是在艾佛瑞特进行。美国空军最近宣布,将以新款747-8取代机龄达到30年的VC-25A作为新一代“空军一号”,并命名为VC-25B。

维基百科的图片说明:E-4B:国家空中指挥中心

图片作者:Juke Schweizer

E-4B – This is an airborne command post designed for use in nuclear war. Three E-4As, based on the 747-200B, with a fourth aircraft, with more powerful engines and upgraded systems delivered in 1979 as a E-4B, with the three E-4As upgraded to this standard.[214][215] Formerly known as the National Emergency Airborne Command Post (referred to colloquially as “Kneecap”), this type is now referred to as the National Airborne Operations Center (NAOC).[215][216]

参考译文:E-4B——这是一架为应对核战争而设计的空中指挥所。三架基于波音747-200B的E-4A,第四架飞机配备了更强大的发动机和升级系统,于1979年交付,作为E-4B,并将前三架E-4A升级到这一标准。[214][215]这架飞机以前被称为国家应急空中指挥所(俗称“膝盖盖”),现在被称为国家空中作战中心(NAOC)。[215][216]

YAL-1 – This was the experimental Airborne Laser, a planned component of the U.S. National Missile Defense.[217]

参考译文:YAL-1——这是实验性的机载激光,是美国国家导弹防御计划的一部分。[217]

维基百科的图片说明:改装为太空梭(航天飞机)运输机的美国航空波音747-100(N905NA),并搭载企业号穿梭机(航天飞机)

Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) – Two 747s were modified to carry the Space Shuttle orbiter. The first was a 747-100 (N905NA), and the other was a 747-100SR (N911NA). The first SCA carried the prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Tests in the late 1970s. The two SCA later carried all five operational Space Shuttle orbiters.[218]

参考译文:航天飞机运输机(SCA)——两架747被改装为运载航天飞机轨道器。第一架是747-100(N905NA),另一架是747-100SR(N911NA)。第一架SCA在20世纪70年代末携带原型企业号进行进场和着陆测试。这两架SCA后来携带了所有五架运营中的航天飞机轨道器。[218]

C-33:美军有意扩充其C-17机队,于是便向波音提案以747-400为基础开发C-33。后来美军改订C-17,C-33计划被取消了。

维基百科的图片说明:波音KC-747空中加油机为伊朗空军的波音747加油

图片作者:iiaf

KC-25/33 – A proposed 747-200F was also adapted as an aerial refueling tanker and was bid against the DC-10-30 during the 1970s Advanced Cargo Transport Aircraft (ACTA) program that produced the KC-10 Extender. Before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Iran bought four 747-100 aircraft with air-refueling boom conversions to support its fleet of F-4 Phantoms.[220] There is a report of the Iranians using a 747 Tanker in H-3 airstrike during Iran–Iraq War.[221] It is unknown whether these aircraft remain usable as tankers. Since then there have been proposals to use a 747-400 for that role.[222]

参考译文:KC-25/33——在20世纪70年代的先进货运运输机(ACTA)项目中,一架拟议中的747-200F也被改装为空中加油机,并在DC-10-30的竞标中产生。在1979年伊朗革命之前,伊朗购买了四架747-100飞机,并进行了空中加油杆改装,以支持其F-4幽灵舰队。[220]有报道称,伊朗人在伊朗-伊拉克战争中使用747加油机进行H-3空袭。[221]目前尚不清楚这些飞机是否仍可作为加油机使用。此后,有人提议使用747-400来执行这一任务。[222]

KC-33A(KC-747):世界最大的一款空中加油机,在美国空军的“先进空中加油及运输机计划”(ATCA)竞标中,因价格昂贵及不能在较短跑道起飞,败给了麦道公司的KC-10,波音急于将其对外出售以挽回亏损,而伊朗巴列维王朝正准备给F-4战斗机配套一种强大的空中加油机,于是便买下了KC-747的所有两架原型机,注册号为5-8113及5-8114。[160][161][160]该等飞机曾于1991及1996年先后改装为民用机,于萨哈航空服役,但最后仍分别于2016及2020年退回伊朗空军,并再次用作加油机[162]。至2000年代,由于澳洲皇家空军的波音707加油机日渐老化,因此向空中巴士订购A330 MRTT,成为该型号加油机的启动客户。其后,有军事专家建议当局改装波音747-400为更大型的加油机,以满足A330 MRTT所无法承担的任务,但提议最后不获接纳。

747F Airlifter – Proposed US military transport version of the 747-200F intended as an alternative to further purchases of the C-5 Galaxy. This 747 would have had a special nose jack to lower the sill height for the nose door. System tested in 1980 on a Flying Tiger Line 747-200F.[223]

参考译文:747F Airlifter——这是747-200F的美国军方运输机版本,旨在替代进一步购买C-5银河。这架747将有一个特殊的鼻子千斤顶,以降低前门的门槛高度。该系统于1980年在飞虎航空公司的747-200F上进行了测试。[223]

747 CMCA – This “Cruise Missile Carrier Aircraft” variant was considered by the U.S. Air Force during the development of the B-1 Lancerstrategic bomber. It would have been equipped with 50 to 100 AGM-86 ALCM cruise missiles on rotary launchers. This plan was abandoned in favor of more conventional strategic bombers.[224]

参考译文:747 CMCA——这种“巡航导弹载机”变体在美国空军开发B-1 Lancer战略轰炸机期间曾被考虑过。它将配备50至100枚AGM-86 ALCM巡航导弹在旋转发射器上。该计划被放弃,转而采用更传统的战略轰炸机。[224]

747 AAC – A Boeing study under contract from the USAF for an “airborne aircraft carrier” for up to 10 Boeing Model 985-121 “microfighters” with the ability to launch, retrieve, re-arm, and refuel. Boeing believed that the scheme would be able to deliver a flexible and fast carrier platform with global reach, particularly where other bases were not available. Modified versions of the 747-200 and Lockheed C-5A were considered as the base aircraft. The concept, which included a complementary 747 AWACS version with two reconnaissance “microfighters”, was considered technically feasible in 1973.[225]

参考译文:波音747 AAC -美国空军与美国波音公司签订合同,研究一种能够搭载10架波音985-121“微型战斗机”的“空中航空母舰”,这些战斗机具备发射、回收、重新装备和加油的能力。波音公司认为,该方案将能够提供一个灵活、快速的全球性航母平台,尤其是在其他基地无法使用的情况下。747-200和洛克希德C-5A的改进型被认为是基本飞机。这个概念包括一个配备两架侦察“微型战斗机”的互补747预警机版本,在1973年被认为是技术上可行的。[225]

Evergreen 747 Supertanker – A Boeing 747-200 modified as an aerial application platform for fire fighting using 20,000 US gallons (76,000 L) of firefighting chemicals.[226]

参考译文:“长青”747超级水箱 – 波音747-200改装为空中消防平台,使用20,000美国加仑(76,000升)的消防化学品。[226]

Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) – A former Pan Am Boeing 747SP modified to carry a large infrared-sensitive telescope, in a joint venture of NASA and DLR. High altitudes are needed for infrared astronomy, to rise above infrared-absorbing water vapor in the atmosphere.[227][228]

参考译文:平流层红外天文台(SOFIA)-美国国家航空航天局和德国航空航天中心合作,将一架泛美航空公司的波音747SP改装成一架大型红外敏感望远镜。红外天文学需要高空观测,以超越大气中吸收红外线的水蒸气。[227][228]

3.11 未开发的子型号 | Undeveloped variants

Boeing has studied a number of 747 variants that have not gone beyond the concept stage.

参考译文:波音公司研究了一些747变体,但它们都没有超越概念阶段。

3.11.1 三发款 | 747 trijet

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Boeing studied the development of a shorter 747 with three engines, to compete with the smaller Lockheed L-1011 TriStar and McDonnell Douglas DC-10. The center engine would have been fitted in the tail with an S-duct intake similar to the L-1011’s. Overall, the 747 trijet would have had more payload, range, and passenger capacity than both of them. However, engineering studies showed that a major redesign of the 747 wing would be necessary. Maintaining the same 747 handling characteristics would be important to minimize pilot retraining. Boeing decided instead to pursue a shortened four-engine 747, resulting in the 747SP.[230]

参考译文:在20世纪60年代末和70年代初,波音公司研究了一种较短的三引擎747飞机的开发,以与较小的洛克希德L-1011三星(TriStar)和麦克唐纳道格拉斯DC-10竞争。中央发动机将安装在尾部,带有类似于L-1011的S型管道进气口。总的来说,747三喷气式飞机将比两者具有更多的有效载荷、航程和乘客容量。然而,工程研究表明,对747机翼进行重大重新设计是必要的。保持相同的747操作特性对于最小化飞行员再培训至关重要。波音公司决定改为研发一种缩短的四引擎747,最终产生了747SP。[230]

3.11.2 747-500

In January 1986, Boeing outlined preliminary studies to build a larger, ultra-long haul version named the 747-500, which would enter service in the mid- to late-1990s. The aircraft derivative would use engines evolved from unducted fan (UDF) (propfan) technology by General Electric, but the engines would have shrouds, sport a bypass ratio of 15–20, and have a propfan diameter of 10–12 feet (3.0–3.7 m).[231] The aircraft would be stretched (including the upper deck section) to a capacity of 500 seats, have a new wing to reduce drag, cruise at a faster speed to reduce flight times, and have a range of at least 8,700 nmi; 16,000 km, which would allow airlines to fly nonstop between London, England and Sydney, Australia.[232]

参考译文:1986年1月,波音公司提出了初步研究,计划制造一款更大、超长航程的飞机,命名为747-500,该飞机将于20世纪90年代中期至晚期投入使用。这款飞机衍生型号将使用由通用电气公司研发的无导管风扇(UDF)(推进风扇)技术改进的发动机,但该发动机将配备罩盖,具有15-20的旁路比,推进风扇直径为10-12英尺(3.0-3.7米)。[231] 该飞机将被拉长(包括上层甲板部分),可容纳500名乘客,配备新型机翼以减少阻力,以更快的速度巡航以减少飞行时间,并且航程至少为8,700海里;16,000公里,这将使航空公司能够在伦敦和悉尼之间直飞。[232]

3.11.3 747 ASB

Boeing announced the 747 ASB (Advanced Short Body) in 1986 as a response to the Airbus A340 and the McDonnell Douglas MD-11. This aircraft design would have combined the advanced technology used on the 747-400 with the foreshortened 747SP fuselage. The aircraft was to carry 295 passengers over a range of 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi).[233] However, airlines were not interested in the project and it was canceled in 1988 in favor of the 777.

参考译文:波音公司在1986年宣布了747 ASB(先进短机身)以回应空中客车A340和麦克唐纳道格拉斯MD-11。这款飞机设计将结合747-400使用的先进技术和缩短的747SP机身。该飞机计划在8,000海里(15,000公里;9,200英里)范围内搭载295名乘客。[233]然而,航空公司对该项目不感兴趣,因此于1988年取消,转而支持777项目。

3.11.4 747-500X, -600X, and -700X

波音公司在1996年的法恩博洛航空展中宣布将会开发747-500X和-600X[80],新飞机的机翼衍生自波音777的机翼,翼展达251英尺(77米),结合前期747的客舱,发动机推力更大和增加了机轮,鼻轮由2个增加至4个,而主机轮则由16个增加至20个[165]。

The 747-500X concept featured a fuselage length increased by 18 feet (5.5 m) to 250 feet (76 m), and the aircraft was to carry 462 passengers over a range up to 8,700 nautical miles (16,100 km; 10,000 mi), with a gross weight of over 1.0 Mlb (450 tonnes).[234] The 747-600X concept featured a greater stretch to 279 feet (85 m) with seating for 548 passengers, a range of up to 7,700 nmi (14,300 km; 8,900 mi), and a gross weight of 1.2 Mlb (540 tonnes).[234]

参考译文:747-500X概念飞机的机身长度增加了18英尺(5.5米),达到250英尺(76米),最大载客量为462人,航程可达8,700海里(16,100公里;10,000英里),总重超过1.0 Mlb(450吨)。[234] 747-600X概念飞机的机身进一步加长至279英尺(85米),可容纳548名乘客,航程可达7,700海里(14,300公里;8,900英里),总重为1.2 Mlb(540吨)。[234]

A third study concept, the 747-700X, would have combined the wing of the 747-600X with a widened fuselage, allowing it to carry 650 passengers over the same range as a 747-400.[91] The cost of the changes from previous 747 models, in particular the new wing for the 747-500X and -600X, was estimated to be more than US$5 billion.[91] Boeing was not able to attract enough interest to launch the aircraft.[92]

参考译文:第三种研究概念是747-700X,它将747-600X的机翼与加宽的机身相结合,使其能够搭载650名乘客,航程与747-400相同。[91] 从之前的747型号进行改进的成本,特别是747-500X和-600X的新机翼,估计超过50亿美元。[91] 波音未能吸引足够的兴趣来推出这款飞机。[92]

3.11.5 747X and 747X Stretch(延长)

As Airbus progressed with its A3XX study, Boeing offered a 747 derivative as an alternative in 2000; a more modest proposal than the previous -500X and -600X that retained the 747’s overall wing design and add a segment at the root, increasing the span to 229 ft (69.8 m).[235] Power would have been supplied by either the Engine Alliance GP7172 or the Rolls-Royce Trent 600, which were also proposed for the 767-400ERX.[236]

参考译文:随着空客A3XX研究的进展,波音在2000年提出了一款747衍生机型作为替代方案;这款方案相较于之前的-500X和-600X更为保守,保留了747的整体机翼设计,并在根部增加了一段,使翼展增加到229英尺(69.8米)。[235]动力将由Engine Alliance GP7172或劳斯莱斯Trent 600提供,这两款发动机也曾被提议用于767-400ERX。[236]

A new flight deck based on the 777’s would be used. The 747X aircraft was to carry 430 passengers over ranges of up to 8,700 nmi (16,100 km; 10,000 mi). The 747X Stretch would be extended to 263 ft (80.2 m) long, allowing it to carry 500 passengers over ranges of up to 7,800 nmi (14,400 km; 9,000 mi).[235] Both would feature an interior based on the 777.[237] Freighter versions of the 747X and 747X Stretch were also studied.[238]

参考译文:新的飞行甲板将基于777的设计。747X飞机将能搭载430名乘客,航程可达8,700海里(16,100公里;10,000英里)。747X Stretch将被延长至263英尺(80.2米)长,使其能够搭载500名乘客,航程可达7,800海里(14,400公里;9,000英里)。[235]两者都将采用基于777的内部设计。[237]747X和747X Stretch的货运版本也进行了研究。[238]

Like its predecessor, the 747X family was unable to garner enough interest to justify production, and it was shelved along with the 767-400ERX in March 2001, when Boeing announced the Sonic Cruiserconcept.[93] Though the 747X design was less costly than the 747-500X and -600X, it was criticized for not offering a sufficient advance from the existing 747-400. The 747X did not make it beyond the drawing board, but the 747-400X being developed concurrently moved into production to become the 747-400ER.[239]

参考译文:与前身类似,747X系列未能吸引足够的兴趣来证明生产是合理的,并于2001年3月与767-400ERX一起搁置,当时波音宣布了Sonic Cruiser概念。[93]尽管747X设计的成本低于747-500X和-600X,但它因未能提供与现有747-400的足够进步而受到批评。747X没有超越绘图板,但同时开发的747-400X进入生产,成为747-400ER。[239]

3.11.6 747-400XQLR

After the end of the 747X program, Boeing continued to study improvements that could be made to the 747. The 747-400XQLR (Quiet Long Range) was meant to have an increased range of 7,980 nmi (14,780 km; 9,180 mi), with improvements to boost efficiency and reduce noise.[240][241] Improvements studied included raked wingtips similar to those used on the 767-400ER and a sawtooth engine nacelle for noise reduction.[242] Although the 747-400XQLR did not move to production, many of its features were used for the 747 Advanced, which was launched as the 747-8 in 2005.[243]

参考译文:在747X项目结束后,波音继续研究对747的改进。747-400XQLR(静音远程)旨在将航程增加到7980海里(14780公里;9180英里),同时提高燃油效率并降低噪音。[240][241]研究的改进包括类似于767-400ER使用的倾斜翼尖和锯齿形发动机舱以降低噪音。[242]尽管747-400XQLR没有投入生产,但其许多功能被用于2005年推出的747 Advanced,即747-8。[243]

4. 运营者 | Operators

Main article: List of Boeing 747 operators

主条目:波音747运营商列表

In 1979, Qantas became the first airline in the world to operate an all Boeing 747 fleet, with seventeen aircraft.[244]

参考译文:1979年,澳洲航空公司成为世界上首家运营全波音747机队的航空公司,共有17架飞机。 [244]

As of July 2019, there were 462 Boeing 747s in airline service, with Atlas Air and British Airways being the largest operators with 33 747-400s each.[245]

参考译文:截至2019年7月,共有462架波音747型飞机在航空公司服役,其中阿特拉斯航空公司和英国航空公司是最大的运营商,分别拥有33架747-400型飞机。[245]

The last US passenger Boeing 747 was retired from Delta Air Lines in December 2017, after it flew for every American major carrier since its 1970 introduction.[246] Delta flew three of its last four aircraft on a farewell tour, from Seattle to Atlanta on December 19 then to Los Angeles and Minneapolis/St Paul on December 20.[247]

参考译文:美国最后一架波音747客机于2017年12月从达美航空公司退役,此前自1970年推出以来,它一直为美国所有主要航空公司服务。[246] 达美航空在其最后四架飞机中的三架进行了告别之旅,12月19日从西雅图飞往亚特兰大,然后于12月20日飞往洛杉矶和明尼阿波利斯/圣保罗。[247]

As the IATA forecast an increase in air freight from 4% to 5% in 2018 fueled by booming trade for time-sensitive goods, from smartphones to fresh flowers, demand for freighters is strong while passenger 747s are phased out. Of the 1,544 produced, 890 are retired; as of 2018, a small subset of those which were intended to be parted-out got $3 million D-checks before flying again. Young -400s were sold for 320 million yuan ($50 million) and Boeing stopped converting freighters, which used to cost nearly $30 million. This comeback helped the airframer financing arm Boeing Capital to shrink its exposure to the 747-8 from $1.07 billion in 2017 to $481 million in 2018.[248]

参考译文:国际航空运输协会预测,由于对时间敏感商品(从智能手机到鲜花)的贸易繁荣,2018年空运货物量将增长4%至5%,因此货机需求强劲,而客机747则逐步退出市场。在生产的1544架747中,有890架已退役;截至2018年,其中一小部分原本计划拆解的飞机在再次飞行前获得了300万美元的D-checks。年轻一代的747-8售价为3.2亿元人民币(合5000万美元),波音公司停止了将货机改装成客机的做法,因为改装成本接近3000万美元。这一复出帮助飞机制造商融资部门波音资本公司将其对747-8的风险敞口从2017年的10.7亿美元降至2018年的4.81亿美元。[248]

In July 2020, British Airways announced that it was retiring its 747 fleet.[249][250] The final British Airways 747 flights departed London Heathrow on October 8, 2020.[251][252]

参考译文:2020年7月,英国航空公司宣布退役其747机队。[249][250] 最后一架英国航空公司的747航班于2020年10月8日从伦敦希思罗机场起飞。[251][252]

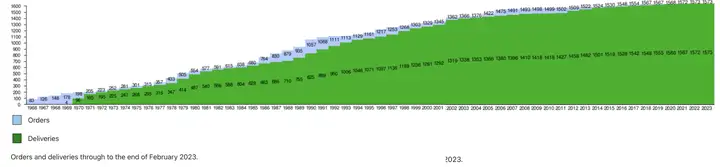

4.1 订单和交付数据 | Orders and deliveries

4.1.1 按年统计(不累加)[1]

4.1.2 历年累加订单和交付量 | Boeing 747 orders and deliveries (cumulative, by year):

4.1.3 分型号统计 | Model summary

5. 意外和故障 | Accidents and incidents

(英文词条)Main article: Boeing 747 hull losses

(中文词条)主条目:波音747飞行事故列表

维基百科的图片说明:波音首架制成的波音747-400客机(N661US),曾担任波音747-400的试验机,试验后卖给作为启始客户的西北航空。于2002年在白令海上发生严重故障,但最终成功迫降安克雷奇国际机场,全机乘员生还。(详情见西北航空85号班机事故)

图片作者:Ken Fielding

As of January 2023, the 747 has been involved in 173 aviation accidents and incidents,[253] including 64 hull loss accidents[254] causing 3,746 fatalities.[255] There have been several hijackings of Boeing 747s, such as Pan Am Flight 73, a 747-100 hijacked by four terrorists, causing 20 deaths.[256]

参考译文:截至2023年1月,波音747已经涉及173起航空事故和事件,其中包括64起机身损失事故,共造成3746人死亡。波音747还发生了几起劫机事件,例如泛美航空公司73号航班,一架747-100型飞机被四名恐怖分子劫持,导致20人死亡。

人为原因引起:

- 1977年的特内里费空难起因是飞行员操作错误、空管员操作错误和沟通问题。造成583人死亡,成为飞航史第一大空难。

- 1985年的日本航空123号班机空难起因是维修不当。世界上涉及单一飞机的空难中死伤人数最多者,也是飞航史上第二大严重空难。

- 2002年的中华航空611号班机空难起因是维修不当。

- 1983年的大韩航空007号班机空难起因是机长的大意,加上苏联战斗机驾驶员对形势的错误判断,还有整条航线上空管的失职导致偏航误入苏联领空而被战机击落,使美国总统里根宣布开放部分的GPS给民间使用。

设计缺陷引起:

- 1989年2月24日的联合航空811号班机起因是货舱门设计错误而在飞行途中打开引致空中爆炸。

- 1996年7月17日的环球航空800号班机空难的空中爆炸,使美国联邦航空局要求大飞机需要在中央油缸加入惰化系统(向油箱充入氮气)。

Few crashes have been attributed to 747 design flaws. The Tenerife airport disaster resulted from pilot error and communications failure, while the Japan Airlines Flight 123 and China Airlines Flight 611 crashes stemmed from improper aircraft repair. United Airlines Flight 811, which suffered an explosive decompression mid-flight on February 24, 1989, led the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to issue a recommendation that the Boeing 747-100 and 747-200 cargo doors similar to those on the Flight 811 aircraft be modified to those featured on the Boeing 747-400. Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was shot down by a Soviet fighter aircraft in 1983 after it had strayed into Soviet territory, causing US President Ronald Reagan to authorize the then-strictly-military global positioning system (GPS) for civilian use.[257]

参考译文:747的设计缺陷导致的坠机事件很少。特内里费机场灾难是由于飞行员失误和通信故障造成的,而日本航空公司123航班和中国航空公司611航班的坠机则是由于飞机维修不当造成的。1989年2月24日,联合航空公司811航班在飞行途中发生爆炸性减压,导致美国国家运输安全委员会(NTSB)建议将波音747-100和747-200货舱门修改为类似于811航班飞机上的货舱门,这些货舱门与波音747-400上的货舱门相似。1983年,大韩航空007航班误入苏联领空后被一架苏联战斗机击落,这导致美国总统罗纳德·里根授权当时严格用于军事的全球定位系统(GPS)用于民用。[257]

Accidents due to design deficiencies included TWA Flight 800, where a 747-100 exploded in mid-air on July 17, 1996, probably due to sparking electrical wires inside the fuel tank.[258] This finding led the FAA to adopt a rule in July 2008 requiring installation of an inerting system in the center fuel tank of most large aircraft, after years of research into solutions. At the time, the new safety system was expected to cost US$100,000 to $450,000 per aircraft and weigh approximately 200 pounds (91 kg).[259] El Al Flight 1862 crashed after the fuse pins for an engine broke off shortly after take-off due to metal fatigue. Instead of simply dropping away from the wing, the engine knocked off the adjacent engine and damaged the wing.[260]