中文词条参见链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):点击这里访问。

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条与原维基百科词条同样遵循CC-BY-SA 4.0协议,在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。文中图片可能遵循不同的共享协议,详见辽观:“辽观百科搬运计划”涉及到的共享协议汇总

目录

0. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

0.1 文字说明

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

华侨华人(英语:Overseas Chinese[30] 或 Chinese diasporas[31]),包括华侨和华人两个概念[32]。其中,华侨一词普遍作为寄居海外中国人的称谓[33]。后指侨居海外,具中华民国国籍或中华人民共和国国籍的公民[34][35]。华裔指华侨华人的后代,具有侨居国国籍。

关于海外华人一词,在中国大陆方面[注 1],根据《中华人民共和国出境入境管理法》,定居境外的华侨应当注销户口[注 2][36],而当华侨加入或取得住在国国籍后,就丧失了中华人民共和国国籍[37],就成为外籍华人[35],也称海外华人,简称华人,在不强调国籍或法律内涵的情况下,华侨、华人有时候会混用,或使用“华侨华人”之综合称谓。在台湾方面[38],因中华民国法律不否认双重国籍,因此中华民国国民加入或取得住在国国籍仍可保留中华民国国籍,被视为华侨[39]或台侨[40][41]。中华民国侨务委员会以“中性包容”为由于2018年在行政规定中开始使用“侨民”来取代“华侨”一词,但表示与传统侨社来住时仍维持“华侨”称呼[42]。中华民国侨务委员会对海外华人的定义为“两岸三地以外之所有旅居海外的华人(包含第一代移民及其后代)”[43]。

注1(中文词条原注):香港、澳门居民因一国两制可有双重国籍。

中国移民史可以上溯到2000多年以前。明清两朝执行“海禁”,出洋谋生被视为非法的行为,因此海外移民被朝廷冠以“逃民”、“罪民”等的消极形象,并不存在真正意义上的华侨。洋务运动之后,清政府对华侨的态度开始转变。中华民国在创立过程中,得到海外华侨的鼎力相助和支持,此后华侨的地位及形象出现了根本性的改变。[44]文化大革命时期,中国大陆有海外关系的人不被信任,又被冠以“特务”、“里通外合”等罪名,也挫伤了海外华侨华人,受到各种歧视、打击和迫害。拨乱反正后,再度为中国的发展做出重大贡献,在人数、文化、政经关系、社会地位均由所恢复提升[45][46]。

鸦片战争前夕,移居国外的中国人达到100万人以上。到20世纪30年代,移居国外的中国人已达1,000万人左右。到1949年中华人民共和国成立时,移居国外的中国人达到1300多万。目前,海外华侨、华人已达数千万人,其中华侨约占10%、外籍华人约占90%,分布在五大洲160多个国家和地区,以东南亚和欧美居多。[37]

0.2 数量及分布

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

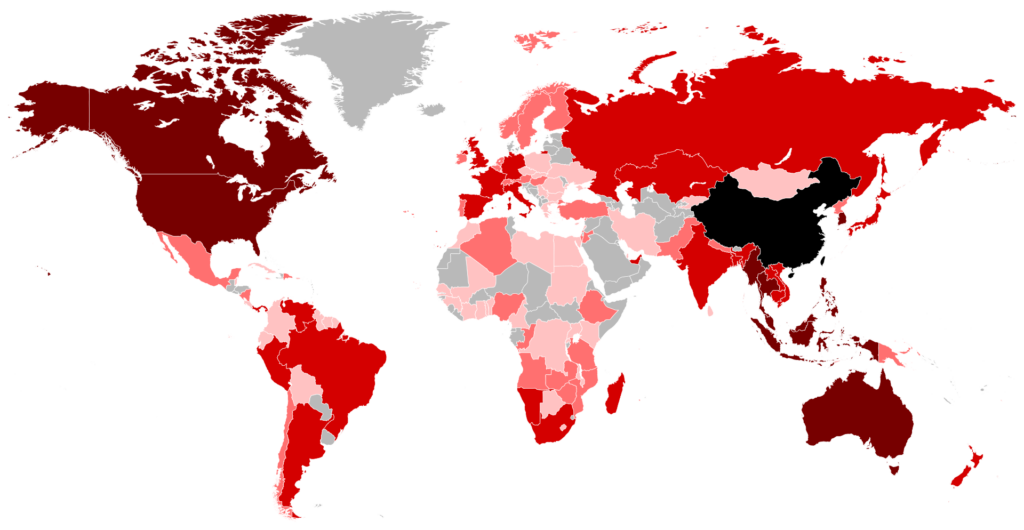

图片题注:Map of the Chinese people around the world. (The map might include people with Chineses ancestries or citizenship) China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau(in black)

参考译文:全球华人地图。(地图上可能包括有中国血统或公民身份的人) 中国、台湾、香港和澳门(图中黑色区域)

图中颜色由深至浅分别代表华人人口数:+ 1,000,000 + 100,000 + 10,000 + 1,000

图片作者:Allice Hunter

| 海外華人 / 海外华人海外中國人 / 海外中国人 | |

|---|---|

| Total population【总人口】 | |

| 60,000,000[1][2][3]【6千万人(2021年)】 | |

| Regions with significant populations【人口众多的地区】 | |

| Thailand【泰国】 | 9,392,792 (2012)[4]【939万(2012年)】 |

| Malaysia【马来西亚】 | 6,884,800 (2022)[5]【688万(2022年)】 |

| United States【美国】 | 5,400,000 (2019)[6]【540万(2019年)】 |

| Indonesia【印度尼西亚】 | 2,832,510 (2010)[7]【283万(2010年)】 |

| Singapore【新加坡】 | 2,675,521 (2020)[8]【267万(2020年)】 |

| Myanmar【缅甸】 | 1,725,794 (2011)[9]【172万(2011年)】 |

| Canada【加拿大】 | 1,715,770 (2021)[10]【171万(2021年)】 |

| Australia【澳大利亚】 | 1,390,639 (2021)[11]【139万(2021年)】 |

| Philippines【菲律宾】 | 1,350,000 (2013)[12]【135万(2013年)】 |

| South Korea【韩国/南朝鲜】 | 1,070,566 (2018)[13]【107万(2018年)】 |

| Vietnam【越南】 | 749,466 (2019)[14]【74万(2019年)】 |

| Japan【日本】 | 744,551 (2022)[15]【74万(2022年)】 |

| Russia【俄罗斯】 | 447,200 (2011)[9]【44万(2011年)】 |

| France【法国】 | 441,750 (2011)[9]【44万(2011年)】 |

| United Kingdom【英国】 | 433,150 (2011)[16]【43万(2011年)】 |

| Italy【意大利】 | 330,495 (2020)[17]【33万(2020年)】 |

| Brazil【巴西】 | 252,250 (2011)[9]【25万(2011年)】 |

| New Zealand【新西兰】 | 247,770 (2018)[18]【24万(2018年)】 |

| Germany【德国】 | 217,000 (2023)[19]【21万(2023年)】 |

| Laos【老挝】 | 176,490 (2011)[9]【17万(2011年)】 |

| Cambodia【柬埔寨】 | 147,020 (2011)[9]【14万(2011年)】 |

| Spain【西班牙】 | 140,620 (2011)[9]【14万(2011年)】 |

| Panama【巴拿马】 | 135,960 (2011)[9]【14万(2011年)】 |

| India【印度】 | 200,000 (2023)[9]【20万(2023年)】 |

| Netherlands【荷兰】 | 111,450 (2011)[9]【11万(2011年)】 |

| South Africa【南非】 | 110,220–400,000 (2011)[9][20]【11万~40万(2011年)】 |

| United Arab Emirates【阿联酋】 | 109,500 (2011)[9]【11万(2011年)】 |

| Saudi Arabia【沙特阿拉伯】 | 14,619 (2022 census) [21][22]【1.5万(2022年普查)】 |

| Brunei【文莱】 | 42,132 (2021)[23]【4.2万(2021年)】 |

| Mauritius【毛里求斯】 | 26,000–39,000【2.6万~3.9万】 |

| Reunion【法属留尼汪】 | 25,000 (2000)【2.5万(2000年)】 |

| Mexico【墨西哥】 | 24,489 (2019)【2.4万(2019年)】 |

| Papua New Guinea 【巴布亚新几内亚】 | 20,000 (2008)[24]【2万(2008年)】 |

| Ireland【爱尔兰】 | 19,447 (2016)【1.9万(2016年)】 |

| Bangladesh【孟加拉国】 | 7,500 |

| Timor Leste【东帝汶】 | 4,000-20,000 (2021)【0.4~2万(2021年)】 |

| Languages | |

| Chinese【汉语/华语/中文】 Cantonese【粤语/广州话】 Hokkien【闽南语】 Hakka【客语/客家话】 Teochew【潮语/潮汕话】 Hainanese【海南话(闽语分支)】 Taishanese【台山话】 etc【其他】 | |

| Religion【宗教信仰】 | |

| Atheism【无神论】 Agnosticism【不可知论】 Taoism【道教】 Buddhism【佛教】 Christianity【基督宗教】 Islam[25]【伊斯兰教】 Other【其他】 | |

| Related ethnic groups【相关族群】 | |

| Chinese people【中华民族】 | |

目前的海外华人主要生活于东南亚、欧洲、北美地区。东南亚因邻近中国,就成为中国移民的目的地。当地为相对多数民族的新加坡及在当地为相对少数民族的马来西亚、泰国、菲律宾、印度尼西亚与越南。这些地区的海外华人,又被称为南洋华侨、南侨,主要来自中国的福建与广东。目前华侨约占10%、各国籍华人约占90%,分布在五大洲160多个国家和地区[66]。其中,东南亚华人约占总数的50%,其次是美洲14.4%,欧洲4.1%,大洋洲1.7%,东亚0.3%,非洲0.3%。中华人民共和国的《世界侨情报告(2020)》蓝皮书称,定居美国的华侨华人数量达508万,日本华侨华人数量突破100万。意大利华侨华人数量持续上升,尤以浙江籍侨胞为多。截止到2018年意大利有华侨华人约30万,西班牙华人约19万。而在2018年有约7000华侨领到了德国签发的“欧盟蓝卡”。[67]

晚清至民国时期,中国移民主要是前往东南亚和北美地区。1940年代海外华侨有1,100万人,其中100万分散在欧美各洲,有1,000万分散在南洋群岛,而这1,000万人中,约有六七百万是广东人,假定广东以3,000万人口计算,每五个人中就有一个是华侨[68];惟而今海外华人总数约为五千万人。

中华人民共和国初期,人口尚可自由流动。其后,人口流动停滞。随着改革开放,自1980年代起,普通民众移民机会增多。随着中国人的收入、教育程度资加,技术移民人数也开始增加,除了欧洲和北美洲,华人人口稀少的澳大利亚、新西兰也成了今天的热门移民地,文化相对近且经济发展的东南亚也有部分移民。而前往遥远非洲、南美洲(如巴西)的也在有所增多[69]。

美加澳新四国华人人口都会区排名

美国数据为2015年资料[91][92],澳大利亚数据为2016年估算资料[93],新西兰为2013年普查数据[94],加拿大为2016年统计数据[95]。

| 都会区主城市 | 华裔人口 | 所占比例 | 所属国 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 纽约 | 739,144 | 3.7% | |

| 多伦多 | 631,045 | 10.8% | |

| 洛杉矶 | 528,248 | 4.0% | |

| 悉尼 | 488,102 | 10.1% | |

| 温哥华 | 474,655 | 19.6% | |

| 旧金山 | 460,252 | 10.2% | |

| 墨尔本 | 356,530 | 7.9% | |

| 圣荷西 | 169,026 | 8.8% | |

| 波士顿 | 133,241 | 2.8% | |

| 奥克兰 | 112,290 | 6.8% | |

| 芝加哥 | 109,046 | 1.1% | |

| 华府 | 105,462 | 1.8% | |

| 布里斯本 | 99,632 | 4.4% | |

| 珀斯 | 99,293 | 5.1% | |

| 西雅图 | 98,949 | 2.7% | |

| 卡加利 | 89,670 | 6.5% | |

| 休士顿 | 86,246 | 1.4% | |

| 蒙特利尔 | 85,925 | 2.2% | |

| 费城 | 82,487 | 1.4% | |

| 沙加缅度 | 61,203 | 2.8% | |

| 埃德蒙顿 | 60,200 | 4.6% | |

| 达拉斯 | 57,325 | 0.8% | |

| 圣地牙哥 | 56,751 | 1.8% | |

| 檀香山 | 53,119 | 5.4% | |

| 河滨市 | 51,628 | 1.2% | |

| 阿德莱德 | 50,247 | 3.9% | |

| 亚特兰大 | 46,859 | 0.8% | |

| 渥太华 | 43,775 | 3.4% | |

| 迈阿密 | 34,210 | 0.6% | |

| 波特兰 | 31,533 | 1.4% | |

| 拉斯维加斯 | 30,329 | 1.5% | |

| 凤凰城 | 28,550 | 0.6% | |

| 明尼阿波利斯 | 24,721 | 0.7% | |

| 底特律 | 24,524 | 0.6% | |

| 巴尔的摩 | 24,092 | 0.9% | |

| 坎京 | 22,486 | 5.7% | |

| 奥斯汀 | 20,182 | 1.1% |

1. 定义(中文)| Terminology

“华”是中国的古称,“华人”在20世纪以前是指汉族,20世纪以来,在狭义上指汉族,广义则包括在文化上与汉族文化具有一体性的人[47]。近代开始,华人、华侨有了法律上的定义,与中国人的含义也有所区别[48]。到1980年代,有将移民中国邻国的少数民族称为“少数民族华侨华人”,有学者统计,约570万少数民族华侨华人目前生活在中国以外的国家和地区。[49]

Huáqiáo (simplified Chinese: 华侨; traditional Chinese: 華僑) or Hoan-kheh (Chinese: 番客; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hoan-kheh) in Hokkien, refers to people of Chinese citizenship residing outside of either the PRC or ROC (Taiwan). The government of China realized that the overseas Chinese could be an asset, a source of foreign investment and a bridge to overseas knowledge; thus, it began to recognize the use of the term Huaqiao.[33]

【参考译文】华侨(简体中文:华侨;繁体中文:華僑)或 Hoan-kheh(中文:番客;白话:Hoan-kheh)在闽南语中指居住在中华人民共和国或中华民国(台湾)以外的中国公民。中国政府意识到海外华人可以成为一笔资产、外国投资的来源和通往海外知识的桥梁;因此,它开始承认使用华侨一词。[33]

Ching-Sue Kuik renders huáqiáo in English as “the Chinese sojourner” and writes that the term is “used to disseminate, reinforce, and perpetuate a monolithic and essentialist Chinese identity” by both the PRC and the ROC.[34]

【参考译文】郭景肃将“华侨”一词译为英文“the Chinese sojourner”(中国的旅居者),并写道,中华人民共和国和中华民国都使用这一术语“来传播、强化和延续单一而本质的华人身份”。[34]

1.1 华侨

“侨”是寄居、客居之意。1878年,清驻美使臣陈兰彬在奏章中把寓居国外的中国人称为“侨民”。1883年郑观应在给李鸿章的奏章中使用了“华侨”一词。1904年,清政府外务部在一份奏请在海外设置领事馆的折子里提到“在海外设领,经费支出无多,而华侨受益甚大。”此后,“华侨”一词就普遍作为寄居海外的中国人尤其是东南亚的中国移民及其后裔的称谓了。[32][33]

1.2 华人

主条目:华人

华人(英语:Ethnic Chinese)除了泛指具有中华民族血统的人士之外,还特指旅居海外不具有中国国籍(大清国籍、中华民国国籍或中华人民共和国国籍)的华裔人士,也称外籍华人或海外华人,例如印尼华人、泰国华人、马来西亚华人、美国华人、加拿大华人、澳大利亚华人等。华裔(英语:Overseas Chinese Descendants)指华人或者华侨在海外(非祖籍国)出生的后代。

图片题注:纽约布鲁克林华埠

图片作者:Eric R. Bechtold

图片题注:日本横滨华埠

图片作者:Aimaimyi

1.3 其他术语

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

The modern informal internet term haigui (simplified Chinese: 海归; traditional Chinese: 海歸) refers to returned overseas Chinese and guīqiáo qiáojuàn (simplified Chinese: 归侨侨眷; traditional Chinese: 歸僑僑眷) to their returning relatives.[35][clarification needed]

【参考译文】现代网络非正式用语“海归”(简体中文:海归;繁体中文:海歸)是指留学回国的中国人,而“归侨侨眷”(简体中文:归侨侨眷;繁体中文:歸僑僑眷)则指这些留学归国人员及其回国后的亲属关系。[35][需澄清]

Huáyì (simplified Chinese: 华裔; traditional Chinese: 華裔; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hôa-è) refers to people of Chinese origin residing outside of China, regardless of citizenship.[36] Another often-used term is 海外華人 (Hǎiwài Huárén) or simply 華人/华人 (Huárén) in Mandarin. It is often used by the Government of the People’s Republic of China to refer to people of Chinese ethnicities who live outside the PRC, regardless of citizenship (they can become citizens of the country outside China by naturalization).

【参考译文】“华裔”是指居住在中国以外地区,不论其国籍如何,具有中国血统的人。另一个常用的术语是海外华人或简称华人,在普通话中通常用华人来表示。这个术语经常被中华人民共和国政府用来指代居住在中国大陆以外的具有中国血统的人,不论其国籍如何(他们可以通过入籍成为中国以外国家的公民)。

Overseas Chinese who are ethnic Han Chinese, such as Cantonese, Hokchew, Hokkien, Hakka or Teochew refer to themselves as 唐人 (Tángrén), pronounced Tòhng yàn in Cantonese, Toung ning in Hokchew, Tn̂g-lâng in Hokkien and Tong nyin in Hakka. Literally, it means Tang people, a reference to Tang dynasty China when it was ruling. This term is commonly used by the Cantonese, Hokchew, Hakka and Hokkien as a colloquial reference to the Chinese people and has little relevance to the ancient dynasty. For example, in the early 1850s when Chinese shops opened on Sacramento St. in San Francisco, California, United States, the Chinese emigrants, mainly from the Pearl River Delta west of Canton, called it Tang People Street (Chinese: 唐人街; pinyin: Tángrén Jiē)[37][38]: 13 and the settlement became known as Tang People Town (Chinese: 唐人埠; pinyin: Tángrén Bù) or Chinatown, which in Cantonese is Tong Yun Fow.[38]: 9–40

【参考译文】海外华人中属于汉族群体的,比如广府人、福清人、闽南人、客家人或潮州人,他们自称为“唐人”(Tángrén),在粤语中发音为Tòhng yàn,福清话中为Toung ning,闽南语读作Tn̂g-lâng,客家话则是Tong nyin。字面意义上,它指的是唐朝时期的人,那时中国正处于强盛的统治时期。这个称呼常被粤语、福清话、客家话及闽南语使用者作为对华人的口语化称谓,实际上与唐朝的历史时代关联不大。例如,在19世纪50年代初,当中国店铺开始在美国加利福尼亚州旧金山的萨克拉门托街上出现时,这些主要来自广州西边珠江三角洲地区的中国移民将其称为“唐人街”(Chinese: 唐人街; pinyin: Tángrén Jiē)[37][38]: 13 ,而这片聚居区随之被称为“唐人埠”(Chinese: 唐人埠; pinyin: Tángrén Bù)或“中国城”,在粤语中即为Tong Yun Fow[38]: 9–40 。

The term shǎoshù mínzú (simplified Chinese: 少数民族; traditional Chinese: 少數民族) is added to the various terms for the overseas Chinese to indicate those who would be considered ethnic minorities in China. The terms shǎoshù mínzú huáqiáo huárén and shǎoshù mínzú hǎiwài qiáobāo (simplified Chinese: 少数民族海外侨胞; traditional Chinese: 少數民族海外僑胞) are all in usage. The Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the PRC does not distinguish between Han and ethnic minority populations for official policy purposes.[35] For example, members of the Tibetan people may travel to China on passes granted to certain people of Chinese descent.[39] Various estimates of the Chinese emigrant minority population include 3.1 million (1993),[40] 3.4 million (2004),[41] 5.7 million (2001, 2010),[42][43] or approximately one tenth of all Chinese emigrants (2006, 2011).[44][45] Cross-border ethnic groups (跨境民族, kuàjìng mínzú) are not considered Chinese emigrant minorities unless they left China after the establishment of an independent state on China’s border.[35]

【参考译文】“少数民族”这一术语会被加入到海外华人的各种称谓中,以标识那些在中国被视为少数族群的人。诸如“少数民族华侨华人”和“少数民族海外侨胞”(简化字:少数民族海外侨胞;繁体字:少數民族海外僑胞)这样的表述均被广泛使用。中华人民共和国国务院侨务办公室在官方政策层面上并不区分汉族与少数民族人群。[35]例如,藏族成员可能凭据给予某些华裔人士的通行证前往中国。[39]对于海外少数民族华人人口的各种估算包括了310万(1993年),[40]340万(2004年),[41]570万(2001年、2010年),[42][43]或是大约占所有海外华人十分之一的比例(2006年、2011年)。[44][45]跨境民族(跨界民族,kuàjìng mínzú)若非在中国边境独立国家成立后离开中国,则不被视为海外华人少数民族。[35]

Some ethnic groups who have historic connections with China, such as the Hmong, may not or may identify themselves as Chinese.[46]

【参考译文】一些与中国有历史渊源的民族,如(海外的)苗族,可能不认为自己是中国人,或者可能认为自己是中国人。[46]

2. 历史 | History

主条目:华人移民史

Main article: Chinese emigration【主条目:中国的向外移民】

The Chinese people have a long history of migrating overseas, as far back as the 10th century. One of the migrations dates back to the Ming dynasty when Zheng He (1371–1435) became the envoy of Ming. He sent people – many of them Cantonese and Hokkien – to explore and trade in the South China Sea and in the Indian Ocean.

【参考译文】中国人民拥有悠久的海外移民历史,远可追溯至10世纪。其中一次大迁移发生在明朝,当时郑和(1371-1435年)成为明朝的使节。他派遣了许多人——其中很多是广府人和闽南人——去探索并在中国南海和印度洋进行贸易。

2.1 古代

中国移民史可以上溯到2000多年以前。据历史记载,汉朝日南郡朱吾县居民不满县吏苛政,逃至屈都昆(今马来西亚登嘉楼)[52]。唐朝贞观年间,僧人孟怀业到佛逝国取经,后留恋佛逝不回故乡[53]。五代时苏门答腊就有中国人耕种,其中巨港华人最多。他们是黄巢起义失败后逃亡至苏门答腊的华侨。宋嘉佑年间,安南虏走大批中国人到安南[54]。中世纪时,有三名中国妇女在东欧定居,并与阿什肯纳兹犹太人结婚[55]。

元朝航海家汪大渊所著《岛夷志略》记载单马锡有华侨定居[56]。唐人到真腊国居住经商会娶真腊女子为妻[57]。洪武三十年(1397年),时旅居三佛齐的华侨一千多人拥戴广东南海人梁道明为三佛齐国王[58]。嘉靖年间,潮州江洋大盗林道干聚集二千余人攻占北大年,因助暹罗王破安南,受暹罗王嘉奖,赐其女与之成婚[59]。

清雍正年间,广东澄海华富里(今汕头市澄海区上华镇)人郑达,南渡暹罗,其子郑昭为暹罗王[60]。婆罗洲戴燕国王吴元盛、昆甸国王罗大均是广东嘉应人[61]。乾隆年间华人罗芳伯在婆罗洲岛上(今加里曼丹西部)成立了“兰芳共和国”。

2.2 清朝中后期

参见:华工

第二次鸦片战争后,清朝的国门被迫打开,加上航运也比古代提高了不少,华人人口开始较大规模地迁徙到世界各地。清代钱庄为长途汇款的便利,需要派驻职员长居海外[62]。

In the mid-1800s, outbound migration from China increased as a result of the European colonial powers opening up treaty ports.[47]: 137 The British colonization of Hong Kong further created the opportunity for Chinese labor to be exported to plantations and mines.[47]: 137

【参考译文】19 世纪中叶,由于欧洲殖民国家开放通商口岸,中国出境移民数量增加。[47]: 137 英国对香港的殖民进一步为中国劳动力输出到种植园和矿山创造了机会。[47]: 137

During the era of European colonialism, many overseas Chinese were coolie laborers.[47]: 123 Chinese capitalists overseas often functioned as economic and political intermediaries between colonial rulers and colonial populations.[47]: 123

【参考译文】欧洲殖民时期,许多海外华人都是苦力。[47]: 123 海外的中国资本家经常充当殖民统治者和殖民地人口之间的经济和政治中间人。[47]: 123

19世纪,华人开始移居东南亚从事金融贸易生意。越南的移民被称为明乡(Minh Hương)或华(Hoa)及不同名称。新加坡最古老的华人墓葬能追溯到1833年,此时华人只占小部分。[63]在康雍乾年间的福建与广东的华裔移民主要是做金融贸易生意为主。由于失业率上升,劳动力过剩,不少广东和福建的失业人口远赴海外谋生,当中广东四邑人多选择移居印度、英国、美国、加拿大、澳洲、新西兰等地。

广东土客冲突时期,很多广东人更成为了契约华工,被卖到美洲的秘鲁、巴拿马、墨西哥、古巴一带。淘金热时期,有人被卖往北美洲、南美洲、大洋洲、南非等地从事危险的工作,如开采金矿与铁路工程等。根据记载,被卖往中美洲的契约华工死亡人数逾半数以上,当中许多人被骗,契约到期也不得回家。在这段时期,成功变得富有的契约华工仅为少数,例如广东的开平碉楼便是契约华工衣锦还乡出资兴建。[64]

The area of Taishan, Guangdong Province was the source for many of economic migrants.[36] In the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong in China, there was a surge in emigration as a result of the poverty and village ruin.[48]

【参考译文】广东省台山地区是许多经济移民的源头。[36] 在中国福建和广东省,由于贫困和村庄破败,移民人数激增。[48]

San Francisco and California was an early American destination in the mid-1800s because of the California Gold Rush. Many settled in San Francisco forming one of the earliest Chinatowns. For the countries in North America and Australia saw great numbers of Chinese gold diggers finding gold in the gold mining and railway construction. Widespread famine in Guangdong impelled many Cantonese to work in these countries to improve the living conditions of their relatives.

【参考译文】19 世纪中期,由于加州淘金热的兴起,旧金山和加州成为美国早期的移民目的地。许多人定居在旧金山,形成了最早的唐人街之一。北美和澳大利亚的黄金开采和铁路建设中,大量中国淘金者发现了黄金。广东的大规模饥荒迫使许多广东人到这些国家工作,以改善亲属的生活条件。

From 1853 until the end of the 19th century, about 18,000 Chinese were brought as indentured workers to the British West Indies, mainly to British Guiana (now Guyana), Trinidad and Jamaica.[49] Their descendants today are found among the current populations of these countries, but also among the migrant communities with Anglo-Caribbean origins residing mainly in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.

【参考译文】从 1853 年到 19 世纪末,约有 18,000 名中国人作为契约劳工被带到英属西印度群岛,主要到英属圭亚那(现圭亚那)、特立尼达和牙买加。[49] 如今,他们的后裔不仅在这些国家的现有人口中发现,而且也在主要居住在英国、美国和加拿大的盎格鲁-加勒比血统的移民群体中发现。

1912年中华民国成立以前,定居在海外的汉族,在书籍上多以“唐人”的名称出现。中华民国成立后,始用“华人”、“华侨”或“海外华人”等。在海外一直以来以均称为唐人,在官话上则称为华人,一些华埠的正式名称为唐人街。迁移海外福建人和广东人因为语言不通,难以交谈良久,遂皆需倚靠各自的会馆和语言群来生存。

Research conducted in 2008 by German researchers who wanted to show the correlation between economic development and height, used a small dataset of 159 male labourers from Guangdong who were sent to the Dutch colony of Suriname to illustrate their point. They stated that the Chinese labourers were between 161 to 164 cm in height for males.[50] Their study did not account for factors other than economic conditions and acknowledge the limitations of such a small sample.

【参考译文】2008 年,德国研究人员进行了一项研究,旨在说明经济发展与身高之间的相关性。他们使用了 159 名广东男性劳工(这些劳工被派往荷属苏里南殖民地)的小型数据集来说明他们的观点。他们指出,中国男性劳工的身高在 161 至 164 厘米之间。[50]他们的研究没有考虑经济条件以外的其他因素,并承认样本量如此之小存在局限性。

The Lanfang Republic (Chinese: 蘭芳共和國; pinyin: Lánfāng Gònghéguó) in West Kalimantan was established by overseas Chinese.

【参考译文】兰芳共和国(中文:蘭芳共和國;拼音:Lánfāng Gònghéguó)位于西加里曼丹,由华侨建立。

In 1909, the Qing dynasty established the first Nationality Law of China.[47]: 138 It granted Chinese citizenship to anyone born to a Chinese parent.[47]: 138 It permitted dual citizenship.[47]: 138

【参考译文】1909 年,清朝制定了中国第一部国籍法。[47]: 138 它授予任何出生在中国人家庭的人中国国籍。[47]: 138 它允许双重国籍。[47]: 138

2.3 中华民国 | Republic of China

辛亥革命成功依靠大量海外华人支持。中华民国《国籍法》接受双重国籍身份,将华裔定义为只要血统上具有华人血缘者,皆为华裔,接受海外华人入籍为中华民国国民,造成了印尼华人国籍问题。

In the first half of the 20th Century, war and revolution accelerated the pace of migration out of China.[47]: 127 The Kuomintang and the Communist Party competed for political support from overseas Chinese.[47]: 127–128

【参考译文】20世纪上半叶,战争与革命加速了海外华侨移民的步伐。[47]: 127 国民党和共产党争夺海外华人的政治支持。[47]: 127–128

Under the Republicans economic growth froze and many migrated outside the Republic of China, mostly through the coastal regions via the ports of Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan and Shanghai. These migrations are considered to be among the largest in China’s history. Many nationals of the Republic of China fled and settled down overseas mainly between the years 1911–1949 before the Nationalist government led by Kuomintang lost the mainland to Communist revolutionaries and relocated. Most of the nationalist and neutral refugees fled mainland China to North America while others fled to Southeast Asia (Singapore, Brunei, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines) as well as Taiwan (Republic of China).[51]

【参考译文】共和时期,经济增长停滞,许多人移居到民国境外,主要通过沿海地区,途径福建、广东、海南和上海等港口。这些移民被认为是中国历史上规模最大的移民之一。许多中华民国国民逃亡并定居海外,主要是在 1911 年至 1949 年之间,之后国民党领导的国民政府将大陆拱手让给共产党革命者,他们不得不重新定居。大多数民族主义者和中立派难民从中国大陆逃往北美,其他人则逃往东南亚(新加坡、文莱、泰国、马来西亚、印度尼西亚和菲律宾)以及台湾(中华民国)。[51]

Those who fled during 1912–1949 and settled down in Singapore and Malaysia and automatically gained citizenship in 1957 and 1963 as these countries gained independence.[52][53] Kuomintang members who settled in Malaysia and Singapore played a major role in the establishment of the Malaysian Chinese Association and their meeting hall at Sun Yat Sen Villa. There was evidence that some intended to reclaim mainland China from the CCP by funding the Kuomintang.[54][55]

【参考译文】1912 年至 1949 年间逃亡的国民党成员在新加坡和马来西亚定居,并在 1957 年和 1963 年这两个国家独立后自动获得公民身份。[52][53] 定居在马来西亚和新加坡的国民党成员在马来西亚华人协会及其位于孙中山别墅的会议厅的建立中发挥了重要作用。有证据表明,一些人打算通过资助国民党从中共手中夺回中国大陆。[54][55]

After their defeat in the Chinese Civil War, parts of the Nationalist army retreated south and crossed the border into Burma as the People’s Liberation Army entered Yunnan.[47]: 65 The United States supported these Nationalist forces because the United States hoped they would harass the People’s Republic of China from the southwest, thereby diverting Chinese resources from the Korean War.[47]: 65 The Burmese government protested and international pressure increased.[47]: 65 Beginning in 1953, several rounds of withdrawals of the Nationalist forces and their families were carried out.[47]: 65 In 1960, joint military action by China and Burma expelled the remaining Nationalist forces from Burma, although some went on to settle in the Burma-Thailand borderlands.[47]: 65–66

【参考译文】国民党军队在中国内战中失败后,部分部队向南撤退,并在人民解放军进入云南时越过边境进入缅甸。[47]: 65 美国支持这些国民党军队,因为美国希望他们从西南骚扰中华人民共和国,从而分散中国在朝鲜战争中的资源。[47]: 65 缅甸政府提出抗议,国际压力也随之增加。[47]: 65 从 1953 年开始,国民党军队及其家属进行了多轮撤离。[47]: 65 1960 年,中缅联合军事行动将剩余的国民党军队驱逐出缅甸,但其中一些人继续在缅泰边境定居。[47]: 65–66

2.4 中华人民共和国

1955年,首任中华人民共和国国务院总理周恩来在参加第一届亚非会议(万隆会议)期间,中国和印度尼西亚签订了《中华人民共和国和印度尼西亚共和国关于双重国籍问题的条约》以期解决印尼华人国籍问题,条约容许持有双重国籍的华人,在条约签署后20年内,成年时选择印尼国籍或中国国籍[65]。1980年颁布的《中华人民共和国国籍法》规定,中华人民共和国不承认中国公民具有双重国籍。1984年起香港前途问题引发香港移民潮。1989年的天安门事件也引发了移民潮。移民潮在1997年香港特别行政区成立之后逐渐平息,而不少移民外国的香港人已回流香港。许多香港原居民和香港人为了改善生活而移居至英国、荷兰等国。

During the 1950s and 1960s, the ROC tended to seek the support of overseas Chinese communities through branches of the Kuomintang based on Sun Yat-sen‘s use of expatriate Chinese communities to raise money for his revolution. During this period, the People’s Republic of China tended to view overseas Chinese with suspicion as possible capitalist infiltrators and tended to value relationships with Southeast Asian nations as more important than gaining support of overseas Chinese, and in the Bandung declaration explicitly stated[where?] that overseas Chinese owed primary loyalty to their home nation.[dubious – discuss]

【参考译文】1950 年代至 1960 年代,中华民国倾向于通过国民党分支机构寻求海外华人社区的支持,这源于孙中山利用海外华人社区为他的革命筹集资金的做法。在此期间,中华人民共和国倾向于怀疑海外华人可能是资本主义渗透者,倾向于重视与东南亚国家的关系,而不是获得海外华人的支持,并在万隆宣言中明确指出[哪里?]海外华人对祖国负有首要的忠诚。[可疑 – 讨论]

From the mid-20th century onward, emigration has been directed primarily to Western countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada, Brazil, The United Kingdom, New Zealand, Argentina and the nations of Western Europe; as well as to Peru, Panama, and to a lesser extent to Mexico. Many of these emigrants who entered Western countries were themselves overseas Chinese, particularly from the 1950s to the 1980s, a period during which the PRC placed severe restrictions on the movement of its citizens.

【参考译文】自 20 世纪中叶以来,移民主要集中于西方国家,如美国、澳大利亚、加拿大、巴西、英国、新西兰、阿根廷和西欧国家,以及秘鲁、巴拿马和墨西哥(数量较少)。这些进入西方国家的移民中,许多本身就是海外华人,尤其是在 1950 年代至 1980 年代,当时中华人民共和国对其公民的流动实行了严格的限制。

Due to the political dynamics of the Cold War, there was relatively little migration from the People’s Republic of China to southeast Asia from the 1950s until the mid-1970s.[47]: 117

【参考译文】由于冷战的政治动态,从 20 世纪 50 年代到 70 年代中期,从中华人民共和国到东南亚的移民相对较少。[47]: 117

In 1984, Britain agreed to transfer the sovereignty of Hong Kong to the PRC; this triggered another wave of migration to the United Kingdom (mainly England), Australia, Canada, US, South America, Europe and other parts of the world. The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre further accelerated the migration. The wave calmed after Hong Kong’s transfer of sovereignty in 1997. In addition, many citizens of Hong Kong hold citizenships or have current visas in other countries so if the need arises, they can leave Hong Kong at short notice.[citation needed]

【参考译文】1984 年,英国同意将香港主权移交给中华人民共和国;这引发了另一波移民潮,移民目的地包括英国(主要是英格兰)、澳大利亚、加拿大、美国、南美、欧洲和世界其他地区。1989 年的天安门广场抗议和屠杀进一步加速了移民潮。1997 年香港主权移交后,移民潮逐渐平息。此外,许多香港公民拥有其他国家的公民身份或有效签证,因此,如果有需要,他们可以在短时间内离开香港。[需要引证]

In recent years, the People’s Republic of China has built increasingly stronger ties with African nations. In 2014, author Howard French estimated that over one million Chinese have moved in the past 20 years to Africa.[56]

【参考译文】近年来,中华人民共和国与非洲国家的关系日益密切。2014 年,作家霍华德·弗伦奇估计,过去 20 年间,已有超过一百万中国人移居非洲。[56]

More recent Chinese presences have developed in Europe, where they number well over 1 million, and in Russia, they number over 200,000, concentrated in the Russian Far East. Russia’s main Pacific port and naval base of Vladivostok, once closed to foreigners and belonged to China until the late 19th century, as of 2010 bristles with Chinese markets, restaurants and trade houses. A growing Chinese community in Germany consists of around 76,000 people as of 2010.[57] An estimated 15,000 to 30,000 Chinese live in Austria.[58]

【参考译文】近来,华人在欧洲发展迅速,人数超过 100 万;在俄罗斯,华人人数超过 20 万,主要集中在俄罗斯远东地区。俄罗斯太平洋主要港口和海军基地符拉迪沃斯托克曾对外国人关闭,直到 19 世纪末才归属中国,但截至 2010 年,这里遍布中国市场、餐馆和贸易公司。截至 2010 年,德国华人群体不断壮大,约有 76,000 人。[57] 据估计,奥地利有 15,000 至 30,000 名华人。[58]

3. 各地华社及侨商商会

3.1 华团

亚洲

- 英属印度

- 广府商至英属印度,和等国就有华团。

- 泰国

- 泰国中华会馆,主席:李那隆

- 马来西亚

- 马来西亚华人公会(政党),主席:联邦交通部长拿督斯里魏家祥

- 砂拉越人民联合党(华基政党),主席:砂地方政府与房屋部长拿督沈桂贤

- 马来西亚中华大会堂总会(华总),总会长:丹斯里吴添泉

- 董教总(教育)

- 马来西亚华校董事联合会总会(董总),主席:陈大锦

- 马来西亚华校教师会总会(教总),主席:拿督王超群

- 马来西亚华人姓氏总会联合会,总会长:拿督斯里洪来喜

- 七大乡团协调委员会[100],主席:拿督张润安

- 福联会

- 客联会

- 潮联会

- 广联会

- 海南联会

- 广西总会

- 三江总会

- 马来西亚留台校友会联合总会,主席:拿督陈绍厚

- 44处属会[101]

- 马来西亚象棋总会,会长:拿督陈川正

- 马来西亚居銮客家公会,会长:拿督张麟言,财政:曾祥忠

| 名称 | 创立时间 | 说明 |

|---|---|---|

| 马来西亚华人公会 | 1949年 | 一个代表马来西亚华人的马来西亚政党[102] |

| 砂拉越人民联合党 | 1959年 | 马来西亚政党 |

| 马来西亚华校教师会总会 | 1951年 | 马来西亚华文教育组织[103] |

| 马来西亚华校董事联合会总会 | 1954年 | 马来西亚华文教育组织[104] |

美洲

- 美国

- 美国亚裔社团联合总会(亚总会)

- 百人会

| 名称 | 创立时间 | 说明 |

|---|---|---|

| 致公堂 | 1848年 | |

| 秉公堂 | 1874年 | 源于洪门致公堂,是旧金山华埠五大侨团之一[105]。 |

| 中华公所 | 1882年 | |

| 安良堂 | 1893年 | 在全美20余个城市设有分会,有超过三万名注册成员,大多数具有商业或工业背景。[106] |

| 布禄仑华人协会 | 1988年 | 位于纽约布鲁克林唐人街的一个非牟利机构,有300多名员工。 |

| 百人会 | 1990年 | 由贝聿铭创立成员来自商界、政界、学术界及文化界[107]。 |

| 美国香港总商会 | 1997年 | 原名“美国香港旅美华人总商会”,美国籍公民成员数量增加,2014年经决议后改称为“美国香港总商会”[108]。 |

欧洲

- 英国

- 英国华侨华人专业人士联合总会

- 意大利

- 意大利旅意福建华侨华人同乡总会,会长:刘炳资

3.2 商会

亚洲[109]

- 泰国中华总商会,主席:陈振治

- 香港中华总商会,会长:蔡冠深

- 日本中华总商会,会长:严浩

- 韩国中华总商会,会长:宋国平

- 菲华商联总会,理事长:黄年荣

- 缅甸中华总商会,会长:吴继垣

- 马来西亚中华总商会(中总),总会长:丹斯里戴良业

- 新加坡中华总商会,会长:黄山忠

- 印尼中华总商会,总主席:纪辉琦[110]

美洲

欧洲

- 英国福清商会,会长:林强

- 西班牙华商协会,会长:杜林飞

大洋洲

- 澳洲维州中华总商会,会长:苏其源[109]

4. 海外境遇 | Overseas Chinese experience

英属印度和东南亚国家的海外华人们已经奠定了他们的商业与财政地位。在北美洲、欧洲与大洋洲,华人所从事的职业则多样化,范围从餐饮业到重要类别如医学、会计、投资、法律、艺术与教育等专业。

华人在各地组织建立了许多华社及侨商商会[109],较知名的有世界福州十邑同乡总会、马来西亚华人公会、砂拉越人民联合党、董教总、马来西亚华校董事联合会总会、马来西亚华校教师会总会、美国亚裔社团联合总会、百人会、美国香港总商会等。

4.1 商业成功 | Commercial success

Main article: Bamboo network【主条目:竹网】

Chinese emigrants are estimated to control US$2 trillion in liquid assets and have considerable amounts of wealth to stimulate economic power in China.[59][60] The Chinese business community of Southeast Asia, known as the bamboo network, has a prominent role in the region’s private sectors.[61][62] In Europe, North America and Oceania, occupations are diverse and impossible to generalize; ranging from catering to significant ranks in medicine, the arts and academia.

【参考译文】据估计,中国移民控制着 2 万亿美元的流动资产,拥有可观的财富来刺激中国的经济实力。[59][60] 东南亚的华人商界被称为“竹网”,在该地区的私营部门发挥着重要作用。[61][62] 在欧洲、北美和大洋洲,华人的职业多种多样,无法一概而论;从餐饮业到医学、艺术和学术界的重要职位。

Overseas Chinese often send remittances back home to family members to help better them financially and socioeconomically. China ranks second after India of top remittance-receiving countries in 2018 with over US$67 billion sent.[63]

【参考译文】海外华人经常向国内家人汇款,帮助他们改善经济和社会经济状况。2018 年,中国是汇款接收国中第二大国家,仅次于印度,汇款金额超过 670 亿美元。[63]

4.2 同化 | Assimilation

Overseas Chinese communities vary widely as to their degree of assimilation, their interactions with the surrounding communities (see Chinatown), and their relationship with China.

【参考译文】海外华人社区在同化程度、与周边社区的互动(见唐人街)以及与中国的关系方面存在很大差异。

Thailand has the largest overseas Chinese community and is also the most successful case of assimilation, with many claiming Thai identity. For over 400 years, descendants of Thai Chinese have largely intermarried and/or assimilated with their compatriots. The present royal house of Thailand, the Chakri dynasty, was founded by King Rama I who himself was partly of Chinese ancestry. His predecessor, King Taksin of the Thonburi Kingdom, was the son of a Chinese immigrant from Guangdong Province and was born with a Chinese name. His mother, Lady Nok-iang (Thai: นกเอี้ยง), was Thai (and was later awarded the noble title of Somdet Krom Phra Phithak Thephamat).

【参考译文】泰国是海外华人最多的国家,也是同化最成功的案例,许多华人都自称泰国人。400 多年来,泰国华人的后裔大多与同胞通婚或同化。泰国现今的王室,即却克里王朝,是由有部分中国血统的拉玛一世建立的。他的前任吞武里王国的郑信国王是一位来自广东的中国移民的儿子,生来就有中文名字。他的母亲诺娇夫人(泰语:นกเอี้ยง)是泰国人(后来被授予 Somdet Krom Phra Phithak Thephamat 贵族头衔)。

英属印度和欧洲外,泰国的一些混血华裔多认同泰国人的身份,没有华人的味道。

在菲律宾,很多年轻的海外华人被彻底同化,然而老一辈的华人则倾向被视为“外国人”。

In the Philippines, the Chinese, known as the Sangley, from Fujian and Guangdong were already migrating to the islands as early as 9th century, where many have largely intermarried with both native Filipinos and Spanish Filipinos (Tornatrás). Early presence of Chinatowns in overseas communities start to appear in Spanish colonial Philippines around 16th century in the form of Parians in Manila, where Chinese merchants were allowed to reside and flourish as commercial centers, thus Binondo, a historical district of Manila, has become the world’s oldest Chinatown.[64]

【参考译文】在菲律宾,来自福建和广东的华人,被称为“Sangley”,早在9世纪就开始迁移到这些岛屿上,其中许多人已与本地菲律宾人及西班牙裔菲律宾人(Tornatrás)广泛通婚。海外华人社区中唐人街的早期形态,大约在16世纪西班牙殖民时期的菲律宾就已显现,表现为马尼拉的帕里安区,那里允许中国商人居住并繁荣发展为商业中心,因此,马尼拉的历史区域——岷伦洛,成为了世界上最古老的唐人街。[64]

Under Spanish colonial policy of Christianization, assimilation and intermarriage, their colonial mixed descendants would eventually form the bulk of the middle class which would later rise to the Principalía and illustrado intelligentsia, which carried over and fueled the elite ruling classes of the American period and later independent Philippines. Chinese Filipinos play a considerable role in the economy of the Philippines[65][66][67][68] and descendants of Sangley compose a considerable part of the Philippine population.[68][69] Ferdinand Marcos, the former president of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos was of Chinese descent, as were many others.[70]

【参考译文】根据西班牙殖民时期的基督教化、同化和通婚政策,这些殖民地混血后代最终形成了中产阶级的主体,他们随后崛起成为显赫的Principalía阶层和illustrado知识精英,这一群体的影响延续到了美国统治时期及后来独立的菲律宾,并支撑着精英统治阶级。[64]菲律宾华人对菲律宾经济起着相当大的作用,[65][66][67][68]而Sangley的后代也构成了菲律宾人口的相当一部分。[68][69]菲律宾前总统费迪南德·马科斯及其他许多人都是华人后裔。[70]

在缅甸,华人很少与当地人通婚(甚至不与讲其它方言的华人通婚),在接受缅甸文化的同时维持华人传统文化。

Myanmar shares. a long border with China so ethnic minorities of both countries have cross-border settlements. These include the Kachin, Shan, Wa, and Ta’ang.[71]

【参考译文】缅甸与中国有漫长的边界,因此两国的少数民族都有跨境定居点。这些少数民族包括克钦族、掸族、佤族和德昂族。[71]

In Cambodia, between 1965 and 1993, people with Chinese names were prevented from finding governmental employment, leading to a large number of people changing their names to a local, Cambodian name. Ethnic Chinese were one of the minority groups targeted by Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian genocide.[72]

【参考译文】在柬埔寨,1965 年至 1993 年间,有中文名字的人无法找到政府工作,导致大量人将自己的名字改为柬埔寨本地名字。华裔是柬埔寨种族灭绝期间波尔布特领导的红色高棉所针对的少数民族之一。[72]

Indonesia forced Chinese people to adopt Indonesian names after the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66.[73]

【参考译文】1965-66 年印尼大屠杀之后,印尼强迫华人采用印尼名字。[73]

华人也为一些国家带来中华文化的影响力,如保留部分中华文化的越南;越战结束后,大批人口逃往海外,未返中国。[112]

In Vietnam, all Chinese names can be pronounced by Sino-Vietnamese readings. For example, the name of the previous paramount leader Hú Jǐntāo (胡錦濤) would be spelled as “Hồ Cẩm Đào” in Vietnamese. There are also great similarities between Vietnamese and Chinese traditions such as the use Lunar New Year, philosophy such as Confucianism, Taoism and ancestor worship; leads to some Hoa people adopt easily to Vietnamese culture, however many Hoa still prefer to maintain Chinese cultural background. The official census from 2009 accounted the Hoa population at some 823,000 individuals and ranked 6th in terms of its population size. 70% of the Hoa live in cities and towns, mostly in Ho Chi Minh city while the rests live in the southern provinces.[74]

【参考译文】在越南,所有中文名字都可以用汉越语读音。例如,前任最高领导人胡锦涛的名字在越南语中拼写为“Hồ Cẩm Đào”。越南和中国的传统也有很大相似之处,例如使用农历新年、儒教、道教和祖先崇拜等哲学;这导致一些华人很容易融入越南文化,但许多华人仍然喜欢保持中国文化背景。2009 年官方人口普查显示,华人人口约为 823,000 人,在人口规模方面排名第六。70% 的华人居住在城镇,主要在胡志明市,其余人居住在南部省份。[74]

马来西亚华人则维持公开的华人身份,并且接受华文教育和保有民间信仰。换句话说,马来西亚华人始终坚持自己的根源,并无被当地人同化。[111]虽然他们有极少数因转变信仰(伊斯兰教)而受同化,但此情况并不常见。

与马来西亚仅有一水之隔的新加坡,华人在当地占大多数。新加坡华人语言以英语和华语为主,并与马来西亚华人一样,保留不少中华文化。

In East Timor, a large fraction of Chinese are of Hakka descent.

【参考译文】在东帝汶,华人中客家人占很大比例。

In Western countries, the overseas Chinese generally use romanised versions of their Chinese names, and the use of local first names is also common.

【参考译文】在西方国家,海外华人一般使用罗马拼音的中文名字,使用当地名字也很常见。

4.3 语言

主条目:海外华人语言 / Main article: Language and overseas Chinese communities

参见:汉姓罗马字标注

海外华人使用的语言除了官话及各种汉语外,也会使用居住国的当地语言。西方国家早期的华人移民通常使用粤语,而近期的华人新移民则使用官话居多。在东南亚,南方汉语(主要为闽南语、潮汕语、粤语、客家话、福州语、四邑话等)则最常被使用。印尼与缅甸皆禁止国民以外文(包括华文)命名;尤其于印尼,华人进入政府工作的前提是懂得印尼语及不通华文。惟至2003年,印尼政府同意海外华人在出生证明上用他们的华文名字或华文姓氏。在越南,华文姓名以越南文拼写。大多数情况越南人与华人姓名没有明显差别。在西方国家,华人普遍使用罗马字母来拼写中文姓名,或加上英文名称(如Amy Chu),而名字使用所在国通用的名字的情况也很普遍。

The usage of Chinese by the overseas Chinese has been determined by a large number of factors, including their ancestry, their migrant ancestors’ “regime of origin”, assimilation through generational changes, and official policies of their country of residence. The general trend is that more established Chinese populations in the Western world and in many regions of Asia have Cantonese as either the dominant variety or as a common community vernacular, while Standard Chinese is much more prevalent among new arrivals, making it increasingly common in many Chinatowns.[104][105]

【参考译文】海外华人使用中文的方式取决于多种因素,包括他们的血统、移民祖先的“原籍制度”、代际同化以及居住国的官方政策。总体趋势是,西方世界和亚洲许多地区较为成熟的华人以粤语为主导或作为社区通用语言,而标准汉语在新移民中更为普遍,在许多唐人街越来越普遍。[104][105]

4.4 歧视 | Discrimination

See also: Sinophobia【另请参阅:恐华症】

主条目:反华情绪

Overseas Chinese have often experienced hostility and discrimination. In countries with small ethnic Chinese minorities, the economic disparity can be remarkable. For example, in 1998, ethnic Chinese made up just 1% of the population of the Philippines and 4% of the population in Indonesia, but have wide influence in the Philippine and Indonesian private economies.[75] The book World on Fire, describing the Chinese as a “market-dominant minority“, notes that “Chinese market dominance and intense resentment amongst the indigenous majority is characteristic of virtually every country in Southeast Asia except Thailand and Singapore”.[76]

【参考译文】海外华人经常遭受敌意和歧视。在华人少数国家,经济差距可能非常显著。例如,1998 年,华人仅占菲律宾人口的 1%,占印度尼西亚人口的 4%,但在菲律宾和印度尼西亚的私营经济中却具有广泛影响力。[75]《世界在火》一书将华人描述为“市场主导的少数群体”,并指出“华人市场主导地位和本土多数群体的强烈不满几乎是除泰国和新加坡外所有东南亚国家的特征”。[76]

This asymmetrical economic position has incited anti-Chinese sentiment among the poorer majorities. Sometimes the anti-Chinese attitudes turn violent, such as the 13 May Incident in Malaysia in 1969 and the Jakarta riots of May 1998 in Indonesia, in which more than 2,000 people died, mostly rioters burned to death in a shopping mall.[77]

【参考译文】这种不对称的经济地位激起了贫穷的大多数人的反华情绪。有时反华情绪会演变成暴力,例如 1969 年马来西亚的 5 月 13 日事件和 1998 年印度尼西亚的雅加达骚乱,当时有超过 2,000 人丧生,其中大部分是购物中心内被烧死的暴徒。[77]

During the Indonesian killings of 1965–66, in which more than 500,000 people died,[78] ethnic Chinese Hakkas were killed and their properties looted and burned as a result of anti-Chinese racism on the excuse that Dipa “Amat” Aidit had brought the PKI closer to China.[79][80] The anti-Chinese legislation was in the Indonesian constitution until 1998.

【参考译文】1965 年至 1966 年,印尼发生大屠杀,造成 50 多万人死亡[78]。作为反华种族主义的产物,客家人华人遭到杀害,财产被抢劫、焚烧,而反华种族主义的借口正是迪帕·“艾买提”·艾迪特让印尼共产党更接近中国。[79][80] 反华立法一直写入印尼宪法,直到 1998 年。

The state of the Chinese Cambodians during the Khmer Rouge regime has been described as “the worst disaster ever to befall any ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia.” At the beginning of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1975, there were 425,000 ethnic Chinese in Cambodia; by the end of 1979 there were just 200,000.[81]

【参考译文】红色高棉政权统治期间柬埔寨华人的境况,被形容为“东南亚华人史上最严重的灾难”。1975 年红色高棉政权统治初期,柬埔寨华人有 42.5 万,而到 1979 年底,只剩下 20 万。[81]

It is commonly held that a major point of friction is the apparent tendency of overseas Chinese to segregate themselves into a subculture.[82][failed verification] For example, the anti-Chinese Kuala Lumpur Racial Riots of 13 May 1969 and Jakarta Riots of May 1998 were believed to have been motivated by these racially biased perceptions.[83] This analysis has been questioned by some historians, notably Dr. Kua Kia Soong, who has put forward the controversial argument that the 13 May Incident was a pre-meditated attempt by sections of the ruling Malay elite to incite racial hostility in preparation for a coup.[84][85] In 2006, rioters damaged shops owned by Chinese-Tongans in Nukuʻalofa.[86] Chinese migrants were evacuated from the riot-torn Solomon Islands.[87]

【参考译文】人们普遍认为,主要的摩擦点是海外华人明显倾向于将自己隔离成一个亚文化群。[82][未能核实]例如,人们认为 1969 年 5 月 13 日的吉隆坡反华种族骚乱和 1998 年 5 月的雅加达骚乱就是受种族偏见驱使。[83]一些历史学家对这种分析提出质疑,尤其是柯嘉宋博士,他提出了一个有争议的论点,即 5 月 13 日事件是马来统治精英的部分人士有预谋的煽动种族敌意,为政变做准备。[84][85]2006 年,暴徒破坏了努库阿洛法的华裔汤加人开设的商店。[86]中国移民被疏散出饱受骚乱蹂躏的所罗门群岛。[87]

Ethnic politics can be found to motivate both sides of the debate. In Malaysia, many “Bumiputra” (“native sons”) Malays oppose equal or meritocratic treatment towards Chinese and Indians, fearing they would dominate too many aspects of the country.[88][89] The question of to what extent ethnic Malays, Chinese, or others are “native” to Malaysia is a sensitive political one. It is currently a taboo for Chinese politicians to raise the issue of Bumiputra protections in parliament, as this would be deemed ethnic incitement.[90]

【参考译文】种族政治是双方争论的动机。在马来西亚,许多“土著”(Bumiputra)马来人反对对华人和印度人实行平等或精英化待遇,担心他们会主宰国家太多方面。[88][89] 马来人、华人或其他族裔在多大程度上是马来西亚的“原住民”,这是一个敏感的政治问题。目前,华裔政客在议会提出保护土著人的问题是一种禁忌,因为这将被视为种族煽动。[90]

Many of the overseas Chinese emigrants who worked on railways in North America in the 19th century suffered from racial discrimination in Canada and the United States. Although discriminatory laws have been repealed or are no longer enforced today, both countries had at one time introduced statutes that barred Chinese from entering the country, for example the United States Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (repealed 1943) or the Canadian Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 (repealed 1947). In both the United States and Canada, further acts were required to fully remove immigration restrictions (namely United States’ Immigration and Nationality Acts of 1952 and 1965, in addition to Canada’s)

【参考译文】19 世纪在北美铁路工作的华侨移民中,许多在加拿大和美国遭受种族歧视。虽然歧视性的法律已被废除或不再执行,但这两个国家都曾一度出台禁止华人入境的法规,例如 1882 年的美国《排华法案》(1943 年废除)和 1923 年的加拿大《华人移民法》(1947 年废除)。美国和加拿大都需要进一步的法案来完全取消移民限制(即美国 1952 年和 1965 年的《移民和国籍法》,以及加拿大的《移民和国籍法》)

In Australia, Chinese were targeted by a system of discriminatory laws known as the ‘White Australia Policy‘ which was enshrined in the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901. The policy was formally abolished in 1973, and in recent years Australians of Chinese background have publicly called for an apology from the Australian Federal Government[91] similar to that given to the ‘stolen generations’ of indigenous people in 2007 by the then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

【参考译文】在澳大利亚,华人成为“白澳政策”歧视性法律体系的目标,该政策被写入 1901 年的《移民限制法》。该政策于 1973 年正式废除,近年来,华裔澳大利亚人公开要求澳大利亚联邦政府道歉[91],类似于 2007 年时任总理陆克文向“被偷走的一代”土著人所致的道歉。

In South Korea, the relatively low social and economic statuses of ethnic Korean-Chinese have played a role in local hostility towards them.[92] Such hatred had been formed since their early settlement years, where many Chinese-Koreans hailing from rural areas were accused of misbehaviour such as spitting on streets and littering.[92] More recently, they have also been targets of hate speech for their association with violent crime,[93][94] despite the Korean Justice Ministry recording a lower crime rate for Chinese in the country compared to native South Koreans in 2010.[95]

【参考译文】在韩国,朝鲜族华人相对较低的社会和经济地位是导致当地人对他们怀有敌意的原因之一。[92] 这种仇恨从他们定居的早期就开始形成了,当时许多来自农村的华裔朝鲜族被指控有随地吐痰和乱扔垃圾等不当行为。[92] 最近,他们还因与暴力犯罪有关联而成为仇恨言论的目标,[93][94] 尽管韩国法务部 2010 年记录显示,该国华人的犯罪率低于韩国本地人。[95]

5. 与中国的关系 | Relationship with China

See also: United front (China) and Ethnic interest group【另请参阅:统一战线(中国)和民族利益集团】

华侨政策以1860年为界可分为前、后两个时期:前期禁止中国人移居国外,限制华侨归国,对海外华侨进行防范与漠视;后期抛弃消极放任政策,对华侨实行保护和监督政策[113]。中华民国与中华人民共和国皆与海外华人有着高度且复杂的关系,皆成立中央部会(侨务委员会及国务院侨务办公室)来处理海外华人事务。中华全国归国华侨联合会是由中华人民共和国归侨、侨眷组成的全国性人民团体和非政府组织,是参加中国人民政治协商会议的人民团体[114]。

Before 2018, the PRC’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Office (OCAO) under the State Council was responsible for liaising with overseas Chinese.[47]: 132 In 2018, the office was merged into the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.[96][47]: 132

【参考译文】2018 年之前,中国国务院侨务办公室负责与海外华侨华人的联络。[47]: 132 2018 年,该办公室并入中共中央统战部。[96][47]: 132

Throughout its existence but particularly during the Xi Jinping administration, the PRC makes patriotic appeals to overseas Chinese to assist the country’s political and economic needs.[47]: 132 In a July 2022 meeting with the United Front Work Department, Xi encouraged overseas Chinese to support China’s rejuvenation and stated that domestic and overseas Chinese should pool their strengths to realize the Chinese Dream.[47]: 132 In the PRC’s view, overseas Chinese are an asset to demonstrating a positive image of China internationally.[47]: 133

【参考译文】中华人民共和国成立以来,特别是在习近平执政期间,一直向海外华人发出爱国呼吁,呼吁他们协助国家的政治和经济需要。[47]: 132 在 2022 年 7 月与统战部举行的会议上,习近平鼓励海外华人支持中国的复兴,并表示国内外华人应该汇聚力量,实现中国梦。[47]: 132 在中华人民共和国看来,海外华人是在国际上展示中国正面形象的宝贵财富。[47]: 133

5.1 公民身份 | Citizenship status

The Nationality Law of the People’s Republic of China, which does not recognise dual citizenship, provides for automatic loss of PRC citizenship when a former PRC citizen both settles in another country and acquires foreign citizenship. For children born overseas of a PRC citizen, whether the child receives PRC citizenship at birth depends on whether the PRC parent has settled overseas: “Any person born abroad whose parents are both Chinese nationals or one of whose parents is a Chinese national shall have Chinese nationality. But a person whose parents are both Chinese nationals and have both settled abroad, or one of whose parents is a Chinese national and has settled abroad, and who has acquired foreign nationality at birth shall not have Chinese nationality” (Article 5).[97]

【参考译文】《中华人民共和国国籍法》不承认双重国籍,规定如果前中华人民共和国公民定居其他国家并获得外国国籍,则自动丧失中华人民共和国国籍。对于中华人民共和国公民在海外出生的子女,该子女是否在出生时获得中华人民共和国国籍取决于其中国父母是否定居海外:“父母双方均为中国公民,或父母一方为中国公民,而本人出生在海外的,具有中国国籍。父母双方均为中国公民定居在海外的,或父母一方为中国公民定居在海外的,本人出生时取得外国国籍的,不具有中国国籍”(第 5 条)。[97]

By contrast, the Nationality Law of the Republic of China, which both permits and recognises dual citizenship, considers such persons to be citizens of the ROC (if their parents have household registration in Taiwan).

【参考译文】相比之下,《中华民国国籍法》既允许也承认双重国籍,并认为此类人是中华民国公民(如果其父母在台湾有户口)。

5.2 侨汇

主条目:侨汇

侨汇是指国际移民将其在国外所得的部分收入向来源国家庭或社区进行的财务或实物转移。侨汇收入曾经是中国外汇的重要来源渠道之一。华侨在1911年为辛亥革命供应了绝大部分革命资金。据海关关册统计,1868~1936年中国外贸入超额累计50亿美元,而同期侨汇总数为24.4亿美元,接近外贸入超额的一半[115]。二战时期,海外华人也提供了中华民国大量财力,支持抗日事业。如1937年侨汇4.74亿元国币,外贸入超1.15亿元,侨汇占入超411%;1938年侨汇6.44亿元,外贸入超1.24 亿元,侨汇占入超521%。这种状况持续到1941年底太平洋战争爆发南洋沦陷前。国民政府依靠侨汇弥补了外贸入超,还利用这些外汇购买军火等战略物资用于抗日[116]。然而由于国共内战,恶性通货膨胀,外汇价格一日数变华侨汇款回国,常遭25%~50%的损失。据统计,1946年中国银行和广东省银行收入侨汇总数约3000万美元,1947年降至1000多万美元,1948年不足500万美元,1949年侨汇几乎断绝[117]。

中华人民共和国成立后,经济条件很差,侨汇是外汇收入的主要来源之一。但出于对中国共产党的疑虑和恐慌,侨汇在1951年达到1.86亿美元后不断减少,在1962年下降至0.5亿多美元,达到历史最低点。为扭转侨汇严重下降局面,中国政府连续颁布多个文件争取侨汇,侨汇因此从60年代中后期到70年代末一直呈上升趋势[118]。到20世纪末,进入中国的外资中60~70%是港台资本,直接来自东南亚华人的资本不到4%[119]。2007年以来,侨汇规模相当于外资规模的50%左右[120]。《世界移民报告2020》称,中国2018年接收的侨汇金额超过670亿美元,成为继印度之后全世界第二大侨汇汇入国。来自中国的移民数量是继来自印度和墨西哥的移民数量之后,世界第三大出生于居住国以外地区的移民群体。[121]

5.3 归侨和再次移民 | Returning and re-emigration

Main article: Haigui【主条目:海归】

主条目:归国华侨

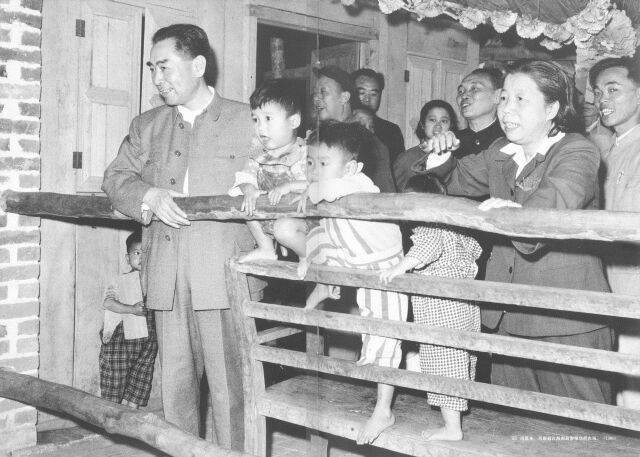

图片题注:1960年2月,周恩来、邓颖超参观海南兴隆华侨农场

归国华侨简称归侨是指海外华侨回到中国作为自己的长期或终身居住地。二战时期有数万华侨回国参战。当时中华民国空军战斗机飞行员中华侨后裔几乎占了四分之三,中华人民共和国开国上将叶飞即是菲律宾归侨,曾参与指挥车桥战役[122]。

中华民国保障海外华侨在立法机关的席次与华侨(侨居国外国民)的选举名额。这些名额由中华民国各个政党在立法院选举(国会改选)时之“政党票”获得的票数比例来分配(侨选立委席次计入全国不分区,两者共选出34席)。大多数当选人具有双重国籍,惟于上任前必须放弃外国国籍,成为完全中华民国国民。

1950~70年代,东南亚华侨为躲避当地排华政策的危害,纷纷返回中国。中国政府成立“华侨事务委员会”,协调与海外华人关系密切的广东、福建、广西、云南等地,新建、扩建了多个华侨农场以紧急安置华侨。[123]

In the case of Indonesia and Burma, political strife and ethnic tensions has caused a significant number of people of Chinese origins to re-emigrate back to China. In other Southeast Asian countries with large Chinese communities, such as Malaysia, the economic rise of People’s Republic of China has made the PRC an attractive destination for many Malaysian Chinese to re-emigrate. As the Chinese economy opens up, Malaysian Chinese act as a bridge because many Malaysian Chinese are educated in the United States or Britain but can also understand the Chinese language and culture making it easier for potential entrepreneurial and business to be done between the people among the two countries.[99]

【参考译文】在印度尼西亚和缅甸,政治纷争和种族紧张导致大量华裔移民回国。在其他拥有大量华人社区的东南亚国家,如马来西亚,中华人民共和国的经济崛起使中国成为许多马来西亚华人重新移民的理想目的地。随着中国经济的开放,马来西亚华人充当了桥梁的作用,因为许多马来西亚华人在美国或英国接受教育,但也能理解中文和中国文化,这使得两国人民之间潜在的创业和商业往来更加容易。[99]

With China’s growing economic strength, many of the overseas Chinese have begun to migrate back to China, even though many mainland Chinese millionaires are considering emigrating out of the nation for better opportunities.[98]

【参考译文】随着中国经济实力的不断增强,许多海外华人开始返回中国,尽管许多中国大陆的百万富翁也在考虑移居国外,寻求更好的机会。[98]

归侨在中华人民共和国占有重要地位,实业家陈嘉庚曾出任中华人民共和国政协副主席一职。不过,中华人民共和国到了文革时期,与海外华人的联系受到严重影响,当时有海外关系甚至会受批斗,许多归侨都受到不公正的待遇。改革开放后,对海外华人的政策恢复到原有水准并得到加强。在1980年代,中华人民共和国尝试积极地在其它方面寻求海外华人的支持,寻求他们的技术与资金来帮助发展。现在,很多海外华人投资中国大陆,提供了包括财政来源、社会与文化网络、互相交流与机会。今日在中华人民共和国,全国人民代表大会设有归国华侨的席次。

After the Deng Xiaoping reforms, the attitude of the PRC toward the overseas Chinese changed dramatically. Rather than being seen with suspicion, they were seen as people who could aid PRC development via their skills and capital. During the 1980s, the PRC actively attempted to court the support of overseas Chinese by among other things, returning properties that had been confiscated after the 1949 revolution. More recently PRC policy has attempted to maintain the support of recently emigrated Chinese, who consist largely of Chinese students seeking undergraduate and graduate education in the West. Many of the Chinese diaspora are now investing in People’s Republic of China providing financial resources, social and cultural networks, contacts and opportunities.[100][101]

【参考译文】邓小平改革开放后,中国对海外华人的态度发生了巨大变化。他们不再被怀疑,而是被视为能够通过技能和资本帮助中国发展的人。20 世纪 80 年代,中国积极争取海外华人的支持,其中包括归还 1949 年革命后被没收的财产。最近,中国的政策试图维持新移民的支持,这些移民主要是寻求在西方接受本科和研究生教育的中国学生。许多海外华人现在正在投资中华人民共和国,提供金融资源、社会和文化网络、联系和机会。[100][101]

The Chinese government estimates that of the 1,200,000 Chinese people who have gone overseas to study in the thirty years since China’s economic reforms beginning in 1978; three-quarters of those who left have not returned to China.[102]

【参考译文】中国政府估计,自 1978 年中国实行经济改革以来的 30 年里,有 120 万中国人出国留学,其中四分之三没有再回国。[102]

Beijing is attracting overseas-trained academics back home, in an attempt to internationalise its universities. However, some professors educated to the PhD level in the West have reported feeling “marginalised” when they return to China due in large part to the country’s “lack of international academic peer review and tenure track mechanisms”.[103]

【参考译文】北京正在吸引海外受训学者回国,试图使大学国际化。然而,一些在西方获得博士学位的教授表示,他们回国后感到“被边缘化”,这在很大程度上是由于中国“缺乏国际学术同行评审和终身教授职位机制”。[103]

A. 参见(维基百科的相关词条)| See also

- 唐人街

- Chinese folk religion & Chinese folk religion in Southeast Asia【中国民间宗教与东南亚中国民间宗教】

- Chinatown, the article and Category:Chinatowns the international category list【唐人街,文章 和 类别:唐人街 国际类别列表】

- Chinese kin, Kongsi & Ancestral shrine【中国亲属、公司和祖祠】

- Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association【中华慈善总会】

- Chinese Americans【华裔美国人】

- Chinese Indonesians【华裔印度尼西亚人】

- Chinese people in India【在印度的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Japan【在日本的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Kenya【在肯尼亚的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Korea【在韩国的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Madagascar【在马达加斯加的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Myanmar【在缅甸的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in New York City【在纽约市的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Nigeria【在尼日利亚的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Papua New Guinea【在巴布亚新几内亚的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Portugal【在葡萄牙的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Spain【在西班牙的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Sri Lanka【在斯里兰卡的华人华侨】

- Chinese people in Turkey【在土耳其的华人华侨】

- Chin Haw【秦霍(来自云南的东南亚移民)】

- List of overseas Chinese【海外中国人/华人列表】

- Migration in China【中国的进出移民】

- Kapitan Cina【華人甲必丹】

- List of politicians of Chinese descent【华裔政治人物列表】

- Overseas Chinese banks【海外的中国银行】

- Legislation on Chinese Indonesians【有关印度尼西亚华人的立法】

- Chinese Exclusion Act (Scott Act, 1888 & Geary Act, 1892) in United States【美国排华法案(1888 年斯科特法案和 1892 年吉里法案)】

- Chinese Immigration Act, 1885 & Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 in Canada【加拿大 1885 年华人移民法和 1923 年华人移民法】

- Chinese head tax & 1886 Vancouver anti-Chinese riots【华人人头税与 1886 年温哥华反华暴乱】

- Lost Years: A People’s Struggle for Justice【《失去的岁月:人民争取正义的斗争》】

- Overseas Chinese Affairs Office【侨务办公室】

B. 参考文献 | References

B1. 英文词条

- ^ “Chinese education companies scramble to teach overseas children to learn Chinese language”. GETChina Insights. 2021 [December 2, 2021].

- ^ Zhuang, Guotu (2021). “The Overseas Chinese: A Long History”. UNESDOC. p. 24.

- ^ Suryadinata, Leo (2017). “Blurring the Distinction between Huaqiao and Huaren: China’s Changing Policy towards the Chinese Overseas”. Southeast Asian Affairs. 2017 (1). Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute: 109. JSTOR pdf/26492596.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ac19f5fdd9d010b9985b476a20a2a8bdd. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ “Chinese Diaspora”. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Current Population Estimates, Malaysia 2022 (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. August 2022. p. 61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ “Chinese in the U.S. Fact Sheet”. ABBY BUDIMAN. April 2021. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ “Jumlah dan Persentase Penduduk menurut Kelompok Suku Bangsa” (PDF). media.neliti.com (in Indonesian). Kewarganegaraan, suku bangsa, agama dan bahasa sehari-hari penduduk Indonesia. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ “Census 2020” (PDF). Singapore Department of Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m Poston, Dudley; Wong, Juyin (2016). “The Chinese diaspora: The current distribution of the overseas Chinese population”. Chinese Journal of Sociology. 2 (3): 356–360. doi:10.1177/2057150X16655077. S2CID 157718431.

- ^ “Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population – Canada [Country] – Visible minority”. Statistics Canada. 15 December 2022. Chinese. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “2021 Australian Census – Quickstats – Australia”. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Macrohon, Pilar (21 January 2013). “Senate declares Chinese New Year as special working holiday” (Press release). PRIB, Office of the Senate Secretary, Senate of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “국내 체류 외국인 236만명…전년比 8.6% 증가”, Yonhap News, 28 May 2019, archived from the original on 27 September 2021, retrieved 1 February 2020

- ^ Jump up to:a b General Statistics Office of Vietnam. “Completed results of the 2019 Viet Nam population and housing census” (PDF) (in Vietnamese). PDF frame 44/842 (within multipaged “43”) Table 2 row “Hoa”. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023. (description page: Completed results of the 2019 Viet Nam population and housing census Archived 21 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ “令和4年6月末現在における在留外国人数について | 出入国在留管理庁”. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ 2011 Census: KS201UK Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom ONS Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ National Institute of Statistics (Italy): I cittadini non comunitari regolarmente soggiornanti Archived November 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 January 2015.17

- ^ “National ethnic population projections, by age and sex, 2018(base)-2043 Information on table”. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ “Statistischer Bericht – Mikrozensus – Bevölkerung nach Migrationshintergrund – Erstergebnisse 2022”. 20 April 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Liao, Wenhui; He, Qicai (2015). “Tenth World Conference of Overseas Chinese: Annual International Symposium on Regional Academic Activities Report (translated)”. The International Journal of Diasporic Chinese Studies. 7 (2): 85–89.

- ^ “Saudi Arabia 2022 Census” (PDF). General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Han Chinese, Mandarin in Saudi Arabia”. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ “Population by Religion, Sex and Census Year”. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ “Papua New Guinea – World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples”. 19 June 2015.

- ^ Ngeow a, Chow Bing; Ma b, Hailong (2018). “More Islamic, no less Chinese: explorations into overseas Chinese Muslim identities in Malaysia”. Chinese Minorities at Home and Abroad. pp. 30–50. doi:10.4324/9781315225159-2. ISBN 978-1-315-22515-9. S2CID 239781552.

- ^ Goodkind, Daniel. “The Chinese Diaspora: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Trends” (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ “Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2”. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ “Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2”. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ “Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010 Supplemental Table 2”. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ John Marzulli (9 May 2011). “Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities”. New York: NY Daily News.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ “Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing”. QueensBuzz.com. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ “SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA Chinese alone”. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Wang, Gungwu (19 December 1994). “Upgrading the migrant: neither huaqiao nor huaren”. Chinese America: History and Perspectives 1996. Chinese Historical Society of America. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-9614198-9-9.

In its own way, it [Chinese government] has upgraded its migrants from a ragbag of malcontents, adventurers, and desperately poor laborers to the status of respectable and valued nationals whose loyalty was greatly appreciated.

- ^ Kuik, Ching-Sue (Gossamer) (2013). “Introduction” (PDF). Un/Becoming Chinese: Huaqiao, The Non-perishable Sojourner Reinvented, and Alterity of Chineseness (PhD thesis). University of Washington. p. 2. OCLC 879349650. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Barabantseva, Elena (2012). “Who Are ‘Overseas Chinese Ethnic Minorities’? China’s Search for Transnational Ethnic Unity”. Modern China. 31 (1): 78–109. doi:10.1177/0097700411424565. S2CID 145221912.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pan, Lynn, ed. (April 1999). “Huaqiao”. The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674252101. LCCN 98035466. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ Hoy, William J (1943). “Chinatown derives its own street names”. California Folklore Quarterly. 2 (April): 71–75. doi:10.2307/1495551. JSTOR 1495551.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Yung, Judy and the Chinese Historical Society of America (2006). San Francisco’s Chinatown. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-07385-3130-4.

- ^ Blondeau, Anne-Marie; Buffetrille, Katia; Wei Jing (2008). Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China’s 100 Questions. University of California Press. p. 127.

- ^ Xiang, Biao (2003). “Emigration from China: a sending country perspective”. International Migration. 41 (3): 21–48. doi:10.1111/1468-2435.00240.

- ^ Zhao, Heman (2004). 少數民族華僑華人研究 [A Study of Overseas Chinese Ethnic Minorities]. Beijing: 華僑出版社.

- ^ Li, Anshan (2001). ‘華人移民社群的移民身份與少數民族’研討會綜述 [Symposium on the Migrant Statuses of Chinese Migrant Communities and Ethnic Minorities]. 華僑華人歷史研究 (in Chinese). 4: 77–78.

- ^ Shi, Canjin; Yu, Linlin (2010). 少數民族華僑華人對我國構建’和諧邊疆’的影響及對策分析 [Analysis of the Influence of and Strategy Towards Overseas Chinese Ethnic Minorities in the Implementation of “Harmonious Borders”]. 甘肅社會科學 (in Chinese). 1: 136–39.

- ^ Ding, Hong (1999). 東干文化研究 [The study of Dungan culture] (in Chinese). Beijing: 中央民族學院出版社. p. 63.

- ^ 在資金和財力上支持對海外少數民族僑胞宣傳 [On finances and resources to support information dissemination towards overseas Chinese ethnic minorities] (in Chinese). 人民網. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ “A study of Southeast Asian youth in Philadelphia: A final report”. Oac.cdlib.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Han, Enze (2024). The Ripple Effect: China’s Complex Presence in Southeast Asia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-769659-0.

- ^ The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present, by Henry K. Norton. 7th ed. Chicago, A.C. McClurg & Co., 1924. Chapter XXIV, pp. 283–96.

- ^ Displacements and Diaspora. Rutgers University Press. 2005. ISBN 9780813536101. JSTOR j.ctt5hj582.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (November 2008). “Anthropometric Trends in Southern China, 1830-1864”. Australian Economic History Review. 43 (3): 209–226. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8446.2008.00238.x.

- ^ “Chiang Kai Shiek”. Sarawakiana. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Yong, Ching Fatt. “The Kuomintang Movement in British Malaya, 1912–1949”. University of Hawaii Press. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ Tan, Kah Kee (2013). The Making of an Overseas Chinese Legend. World Scientific Publishing Company. doi:10.1142/8692. ISBN 978-981-4447-89-8.

- ^ Jan Voon, Cham (2002). “Kuomintang’s influence on Sarawak Chinese”. Sarawak Chinese political thinking : 1911–1963 (master thesis). University of Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS). Retrieved 28 August 2012. [permanent dead link]

- ^ Wong, Coleen (10 July 2013). “The KMT Soldiers Who Stayed Behind In China”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ French, Howard (November 2014). “China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa”. Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ “Deutsch-Chinesisches Kulturnetz”. De-cn.net (in German). Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ “Heimat süßsauer” (PDF). Eu-china.net (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Bartlett, David (1997). The Political Economy of Dual Transformations: Market Reform and Democratization in Hungary. University of Michigan Press. p. 280. ISBN 9780472107940.

- ^ Fukuda, Kazuo John (1998). Japan and China: The Meeting of Asia’s Economic Giants. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7890-0417-8. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Murray L Weidenbaum (1 January 1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia. Martin Kessler Books, Free Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-684-82289-1.

- ^ “The world’s successful diasporas”. Worldbusinesslive.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ “India to retain top position in remittances with $80 billion: World Bank”. The Economic Times. 8 December 2018. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ See, Stanley Baldwin O. (17 November 2014). “Binondo: New discoveries in the world’s oldest Chinatown”. GMA News Online. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. pp. 3, 6. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- ^ Gambe, Annabelle (2000). Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 33. ISBN 978-0312234966.

- ^ Folk, Brian (2003). Ethnic Business: Chinese Capitalism in Southeast Asia. Routledge. p. 93. ISBN 978-1138811072.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Chirot, Daniel; Reid, Anthony (1997). Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. University of Washington Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780295800264. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ “Genographic Project – Reference Populations – Geno 2.0 Next Generation”. National Geographic. 13 April 2005. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019.

- ^ Tan, Antonio S. (1986). “The Chinese Mestizos and the Formation of the Filipino Nationality”. Archipel. 32 (1): 141–162. doi:10.3406/arch.1986.2316.

- ^ “Ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia’s Borderland: Assessing Chinese Nationalism in Upper Shan State”. LSE Southeast Asia Blog. 14 March 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ “Khmer Rouge | Facts, Leadership, Genocide, & Death Toll | Britannica”. www.britannica.com. 11 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Post, The Jakarta. “More Chinese-Indonesians using online services to find their Chinese names – Community”. The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ General Statistics Office of Vietnam. “Kết quả toàn bộ Tổng điều tra Dân số và Nhà ở Việt Nam năm 2009–Phần I: Biểu Tổng hợp” [The 2009 Vietnam Population and Housing census: Completed results] (PDF) (in Vietnamese). p. 134/882. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2012. (description page: The 2009 Vietnam Population and Housing census: Completed results Archived 15 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Amy Chua, “World on Fire”, 2003, Doubleday, pp. 3, 43.

- ^ Amy Chua, “World on Fire”, 2003, Doubleday, p. 61.

- ^ Malaysia’s race rules Archived 10 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Economist Newspaper Limited (25 August 2005). Requires login.

- ^ Indonesian academics fight burning of books on 1965 coup Archived 10 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Sydney Morning Herald

- ^ Vickers (2005), p. 158

- ^ “Analysis – Indonesia: Why ethnic Chinese are afraid”. BBC. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–314.

- ^ Palona, Iryna (2010). “Asian Megatrends and Management Education of Overseas Chinese” (PDF). International Education Studies. 3. United Kingdom: 58–65. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2017 – via Education Resources Information Center.

- ^ Michael Shari (9 October 2000). “Wages of Hatred”. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 11 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Baradan Kuppusamy (14 May 2007). “Politicians linked to Malaysia’s May 13 riots”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022.

- ^ “May 13 by Kua Kia Soong”. Littlespeck.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ “Editorial: Racist moves will rebound on Tonga”. The New Zealand Herald. 23 November 2001. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Spiller, Penny: “Riots highlight Chinese tensions Archived 2 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine“, BBC, 21 April 2006

- ^ Chin, James (27 August 2015). “Opinion | The Costs of Malay Supremacy”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Ian Buruma (11 May 2009). “Eastern Promises”. The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Vijay Joshi (31 August 2007). “Race clouds Malaysian birthday festivities”. Independent Online. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ The World Today Barbara Miller (30 June 2011). “Chinese Australians want apology for discrimination”. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hyun-ju, Ock (24 September 2017). “[Feature] Ethnic Korean-Chinese fight ‘criminal’ stigma in Korea”. The Korea Herald. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020.

- ^ “Anti Chinese-Korean Sentiment on Rise in Wake of Fresh Attack”. KoreaBANG. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021.

- ^ “Hate Speech against Immigrants in Korea: A Text Mining Analysis of Comments on News about Foreign Migrant Workers and Korean Chinese Residents* (page 281)” (PDF). Seoul National University. Ritsumeikan University. January 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2020.

- ^ Ramstad, Evan (23 August 2011). “Foreigner Crime in South Korea: The Data”. Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022.

- ^ Joske, Alex (9 May 2019). “Reorganizing the United Front Work Department: New Structures for a New Era of Diaspora and Religious Affairs Work”. Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ “Nationality Law of the People’s Republic of China”. china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ “Report: Half of China’s millionaires want to leave”. CNN. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012.

- ^ “Will China’s rise shape Malaysian Chinese community?”. BBC. 30 December 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ JIEH-YUNG LO (6 March 2018). “Beijing’s welcome mat for overseas Chinese”. Lowy Institute. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Richard D. Lewis (2003). The Cultural Imperative. Intercultural Press. ISBN 9780585434902. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Zhou, Wanfeng (17 December 2008). “China goes on the road to lure ‘sea turtles’ home”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ Lau, Joyce (21 August 2020). “Returning Chinese scholars ‘marginalised’ at home and abroad”. Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022.

- ^ West (2010), pp. 289–90

- ^ Pierson, David (31 March 2006). “Dragon Roars in San Gabriel”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ 張明愛 (11 March 2012). “Reforms urged to attract overseas Chinese”. China.org.cn. Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ “President meets leaders of overseas Chinese organizations”. English.gov.cn. 9 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Wang, Huiyao (24 May 201). “China’s Competition for Global Talents: Strategy, Policy and Recommendations” (PDF). Asia Pacific. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Liao, Wenhui; He, Qicai (2015). “Tenth World Conference of Overseas Chinese: Annual International Symposium on Regional Academic Activities Report (translated)”. The International Journal of Diasporic Chinese Studies. 7 (2): 85–89.

- ^ Tremann, Cornelia (December 2013). “Temporary Chinese Migration to Madagascar: Local Perceptions, Economic Impacts, and Human Capital Flows” (PDF). African Review of Economics and Finance. 5 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ “Zambia has 13,000 Chinese”. Zambia Daily Mail News. 21 March 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Cook, Seth; Lu, Jixia; Tugendhat, Henry; Alemu, Dawit (May 2016). “Chinese Migrants in Africa: Facts and Fictions from the Agri-Food Sector in Ethiopia and Ghana”. World Development. 81: 61–70. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.011.

- ^ “China empowers a million Ethiopians: ambassador”. Africa News Agency. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ “Chinese Businesses Quit Angola After ‘Disastrous’ Currency Blow”. Bloomberg. 20 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ “China-Nigeria’s trade volume declining very fast –Chinese Ambassador”. The Sun. 20 February 2017. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ “Marutians of Chinese Origins”. mychinaroots. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Chinese, Algerians fight in Algiers – witnesses Archived 26 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters. 4 August 2009.

- ^ Tagy, Mwakawago (14 January 2013). “Dar-Beijing for improved diplomatic-ties”. Daily News. Dar es Salaam. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ “reunion statistics”. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, September 22). Réunion. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2000. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Horta, Loro. “China, Mozambique: old friends, new business”. International Relations and Security Network. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Lo, Kinling (17 November 2017). “How Chinese living in Zimbabwe reacted to Mugabe’s downfall: ‘it’s the most hopeful moment in 20 years'”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Sautman, Barry; Yan Hairong (December 2007). “Friends and Interests: China’s Distinctive Links with Africa” (PDF). African Studies Review. 50 (3): 89. doi:10.1353/arw.2008.0014. S2CID 132593326. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2014.

- ^ Situma, Evelyn (7 November 2013). “Kenya savours, rues China moment”. Business Daily. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Jaramogi, Pattrick (18 February 2013), Uganda: Chinese Investments in Uganda Now At Sh1.5 Trillion, archived from the original on 29 December 2014, retrieved 20 February 2013

- ^ ‘The Oriental Post’: the new China–Africa weekly, France 24, 10 July 2009, archived from the original on 15 July 2009, retrieved 26 August 2009

- ^ “Somalis in Soweto and Nairobi, Chinese in Congo and Zambia, local anger in Africa targets foreigners”. Mail & Guardian. 25 January 2015. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Aurégan, Xavier (February 2012). “Les “communautés” chinoises en Côte d’Ivoire”. Working Papers, Working Atlas. Institut Français de Géopolitique. doi:10.58079/p05i. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ “China–Mali relationship: Finding mutual benefit between unequal partners” (PDF). Centre for Chinese Studies Policy Briefing. January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Horta, Loro (2 January 2008). “China in Cape Verde: the Dragon’s African Paradise”. Online Africa Policy Forum. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ “Chinese in Rwanda”. Public Radio International. 17 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ “Chinese traders shake up Moroccan vendors”. Agence France-Presse. 24 September 2004. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ “1999 年底非洲國家和地區華僑、華人人口數 (1999 year-end statistics on Chinese expatriate and overseas Chinese population numbers in African countries and territories)”. Chinese Language Educational Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ “508 Chinese evacuated from Libya”. Xinhua News Agency. 2 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014.

- ^ West, Barbara A. (2009), Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, Facts on File, p. 794, ISBN 978-1438119137

- ^ Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010. Badan Pusat Statistik. 2011. ISBN 9789790644175. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ “Population in Brief 2015” (PDF). Singapore Government. September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ “International Migrant Stock 2020”. United Nations. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

This figure includes people who are of Chinese origin in Singapore, not including the Taiwanese population in Singapore

- ^ “Burma”. The World Factbook. Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ “Burma”. State.gov. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ “PRIB: Senate declares Chinese New Year as special working holiday”. Senate.gov.ph. 21 January 2013. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ “在日华人统计人口达92万创历史新高”. rbzwdb.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Nhean, Moeun. “Chinese New Year: family, food and prosperity for the year ahead”. www.phnompenhpost.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “The World Factbook”. Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ “Chinese expats in Dubai”. Time Out Dubai. 3 August 2008. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ “Chinese influence outpaces influx”. Dawn. 22 January 2018. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ “Economic Planning And Development, Prime Minister’s Office”. Prime Minister’s Office, Brunei Darussalam. 2015. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ “Appeal to international organisations – Stop the China-Israel migrant worker scam!” (Press release). Kav La’Oved. 21 December 2001. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2006.

- ^ “Chinese in N. Korea ‘Face Repression'”. Chosun Ilbo. 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 October 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ “僑委會全球資訊網”. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011.

- ^ “Qatar’s population by nationality”. Bq Magazine. 12 July 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Huber, Juliette (1 September 2021). “Chapter 2 At the Periphery of Nanyang: The Hakka Community of Timor-Leste”. Chinese Overseas. 20pages=52–90. doi:10.1163/9789004473263_004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ “Chinese population statistics – Countries compared”. NationMaster. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ 馬敏/Ma Min (1 April 2009), “新疆《哈薩克斯坦華僑報》通過哈方註冊 4月底創刊/Xinjiang ‘Kazakhstan Overseas Chinese Newspaper’ Passes Kazakhstan Registration; To Begin Publishing at Month’s end”, Xinhua News, archived from the original on 20 July 2011, retrieved 17 April 2009

- ^ Population and Housing Census 2009. Chapter 3.1. Resident population by nationality (PDF) (in Russian), Bishkek: National Committee on Statistics, 2010, archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2016, retrieved 14 December 2021

- ^ Ousselin, Edward, ed. (2018). La France: histoire, société, culture. Toronto: Canadian Scholars. p. 229. ISBN 9781773380643. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ “Italy: foreign residents by country of origin”. Statista. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ “Spain: foreign population by nationality 2022”. Statista. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ “Federal Statistical Office Germany – GENESIS-Online”. www-genesis.destatis.de. 26 April 2021. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ “Utrikes födda efter födelseland – Hong Kong + China + Taiwan”. SCB Statistikdatabasen. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ “НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ СОСТАВ НАСЕЛЕНИЯ” [National Composition of the Population] (PDF) (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2021.

- ^ “Relatório de Imigração, Fronteiras e Asilo” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ “Ausländerstatistik Juni 2019”. sem.admin.ch. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ “Census of Population 2016 – Profile 8 Irish Travellers, Ethnicity and Religion”. Cso.ie. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ “Overseas Chinese Associations in Austria”. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Tilastokeskus. “Tilastokeskus”. www.stat.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ “Population by nationalities in detail 2011 – 2020”. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ “Η ζωή στην China Town της Θεσσαλονίκης” [Life in China Town, Thessaloniki]. 8 September 2017. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ “Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији: Становништво према националној припадности – “Остали” етничке заједнице са мање од 2000 припадника и двојако изјашњени” (PDF). Webrzs.stat.gov.rs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Statistikaamet (31 December 2011). Population by Ethnic Nationality, Sex and Place of Residence. Statistikaamet. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.