中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原文连接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。

关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及其他已搬运的词条,请点击这里了解更多。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

目录

- 0. 导言

- 1. 概况 | Overview

- 2. 现代争论 | Modern debates

- 3. 思想史 | Intellectual history

- 4. 国际组织 | International organizations

- 5. 在各国的历史 | History by country

- 5.1 非洲 | Africa

- 5.2 美洲 | Americas

- 5.3 亚洲 | Asia

- 5.4 欧洲 | Europe

- 5.4.1 亚美尼亚 | Armenia

- 5.4.2 克罗地亚 | Croatia

- 5.4.3 爱沙尼亚 | Estonia

- 5.4.4 芬兰 | Finland

- 5.4.5 法国 | France

- 5.4.6 德国 | Germany

- 5.4.7 希腊 | Greece

- 5.4.8 意大利 | Italy

- 4.3.9 荷兰 | Netherlands

- 5.4.10 波兰 | Poland

- 5.4.11 罗马尼亚 | Romania

- 5.4.12 俄罗斯 | Russia

- 5.4.13 塞尔维亚 | Serbia

- 5.4.14 斯洛文尼亚 | Slovenia

- 5.4.15 西班牙 | Spain

- 5.4.16 英国 | United Kingdom

- 5.4.16 其他国家和地区

- 5.5 大洋洲 | Oceania

- 5.6 泛民族主义 | Pan-national

- 6. 在网络上 | Online

- 7. 右翼恐怖主义 | Right-wing terrorism

- 8. 原各地组织

- 参见、参考文献、外部链接

0. 导言

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

图片题注:Prominent far-rightists during the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Pictured are rally participants carrying Confederate battle flags, Gadsden flags, and a Nazi flag.

参考译文:2017 年弗吉尼亚州夏洛茨维尔“团结右翼”集会上著名的极右翼分子。图中是集会参与者携带邦联战旗、盖兹登旗和纳粹旗。

图片来源:Anthony Crider

极右派(英语:Far-right politics),又称极右翼,是指其政治立场位于政治光谱最右端的人士或组织。“极右”也常被许多政治评论家用来描述一些难以归入传统右派的政治团体、运动和政党。[1]促进和持有极端保守主义、极端民族主义和威权主义的立场或言论的运动或政党也被描述为极右翼。 [2]

Historically, “far-right politics” has been used to describe the experiences of fascism, Nazism, and Falangism. Contemporary definitions now include neo-fascism, neo-Nazism, the Third Position, the alt-right, racial supremacism and other ideologies or organizations that feature aspects of authoritarian, ultra-nationalist, chauvinist, xenophobic, theocratic, racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, or reactionary views.[2]

【参考译文】历史上,“极右政治”曾被用来描述法西斯主义、纳粹主义和长枪党主义的经历。当代定义现在还包括新法西斯主义、新纳粹主义、第三位置主义、另类右翼、种族至上主义以及其他具有权威主义、极端民族主义、沙文主义、仇外心理、神权政治、种族主义、性别歧视、恐同、跨性别恐惧或反动观点等特点的意识形态或组织。[2]

一些学者使用“极端右派”(Extreme Right)或“偏激右派”(Ultra Right)来讨论位于传统选举政治范围以外的右派政治团体,通常有革命右派份子、好战的种族至上主义者和宗教极端主义者、新法西斯主义者、新纳粹主义者和三K党员等。在这种用法中,该名词与不好战的极右派或右派民粹主义者等其他形式的极右派有所区别。[1][3]

倾向改革的右派运动或保守派政党中的右翼派系,他们常被称为“不同政见的右派”(Dissident Right)、“行动主义右派”(Activist Right)或“右翼民粹主义”(Right-wing Populism)。他们的立场介于传统保守派和极端右派之间。这些人士位于主流选举政治之外,但他们一般是发起改革运动,而非革命。一些被认为的“极右派”的政党则是因为与原主流中间偏右保守主义政党意见不合,认为他们的政策和理念已偏离原来的右派路线,如英国独立党。

Far-right politics have led to oppression, political violence, forced assimilation, ethnic cleansing, and genocide against groups of people based on their supposed inferiority or their perceived threat to the native ethnic group, nation, state, national religion, dominant culture, or conservative social institutions.[3]

【参考译文】极右政治导致了针对某些群体的压迫、政治暴力、强制同化、种族清洗和种族灭绝,这些行为基于对这些群体所谓的低劣性或他们对本土族群、国家、民族、国家宗教、主流文化或保守社会制度构成的威胁的认知。[3]

新法西斯主义者与新纳粹主义者时常被视为“极右派”或“偏激右派”。这些团体通常具有反革命性质。新法西斯和新纳粹也意指他们来自二战之后的时代。

由于这些分类尚未普遍被接受,以及还有其他的用法存在,因此让“极右派”的用法较为复杂。

1. 概况 | Overview

1.1 概念与世界观 | Concept and worldview

图片题注:Benito Mussolini, dictator and founder of Italian Fascism, a far-right ideology

参考译文:贝尼托·墨索里尼,意大利法西斯主义的独裁者与创始人,法西斯主义是一种极右意识形态

According to scholars Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg, the core of the far right’s worldview is organicism, the idea that society functions as a complete, organized and homogeneous living being. Adapted to the community they wish to constitute or reconstitute (whether based on ethnicity, nationality, religion or race), the concept leads them to reject every form of universalism in favor of autophilia and alterophobia, or in other words the idealization of a “we” excluding a “they”.[4] The far right tends to absolutize differences between nations, races, individuals or cultures since they disrupt their efforts towards the utopian dream of the “closed” and naturally organized society, perceived as the condition to ensure the rebirth of a community finally reconnected to its quasi-eternal nature and re-established on firm metaphysical foundations.[5][6]

【参考译文】根据学者让-伊夫·加缪和尼古拉斯·勒布尔的说法,极右翼世界观的核心是有机论,即社会作为一个完整、有组织、同质的生物体而运作。根据他们希望建立或重建的社区(无论是基于种族、国籍、宗教还是种族),这一概念使他们拒绝一切形式的普遍主义,转而支持自恋和异化恐惧症,换句话说,理想化“我们”而排除“他们”。[4] 极右翼倾向于将国家、种族、个人或文化之间的差异绝对化,因为这会破坏他们实现“封闭”和自然组织社会的乌托邦梦想的努力,而乌托邦梦想被视为确保社区重生的条件,最终重新与其准永恒性质联系起来,并在坚实的形而上学基础上重建。[5][6]

As they view their community in a state of decay facilitated by the ruling elites, far-right members portray themselves as a natural, sane and alternative elite, with the redemptive mission of saving society from its promised doom. They reject both their national political system and the global geopolitical order (including their institutions and values, e.g. political liberalism and egalitarian humanism) which are presented as needing to be abandoned or purged of their impurities, so that the “redemptive community” can eventually leave the current phase of liminal crisis to usher in the new era.[4][6] The community itself is idealized through great archetypal figures (the Golden Age, the savior, decadence and global conspiracy theories) as they glorify non-rationalistic and non-materialistic values such as the youth or the cult of the dead.[4]

【参考译文】极右翼成员认为,他们的社区正处于统治精英的腐朽状态,因此将自己描绘成一个自然、理智和另类的精英,肩负着拯救社会免于毁灭的救赎使命。他们拒绝接受国家政治制度和全球地缘政治秩序(包括他们的制度和价值观,例如政治自由主义和平等人文主义),认为这些制度和价值观需要被抛弃或清除其中的杂质,以便“救赎社区”最终能够摆脱当前的危机阶段,迎来新时代。[4][6] 社区本身通过伟大的原型人物(黄金时代、救世主、颓废和全球阴谋论)被理想化,因为他们美化了非理性主义和非物质主义的价值观,例如青春或死者崇拜。[4]

Political scientist Cas Mudde argues that the far right can be viewed as a combination of four broadly defined concepts, namely exclusivism (e.g. racism, xenophobia, ethnocentrism, ethnopluralism, chauvinism, including welfare chauvinism), anti-democratic and non-individualist traits (e.g. cult of personality, hierarchism, monism, populism, anti-particracy, an organicist view of the state), a traditionalist value system lamenting the disappearance of historic frames of reference (e.g. law and order, the family, the ethnic, linguistic and religious community and nation as well as the natural environment[7]) and a socioeconomic program associating corporatism, state control of certain sectors, agrarianism, and a varying degree of belief in the free play of socially Darwinistic market forces. Mudde then proposes a subdivision of the far-right nebula into moderate and radical leanings, according to their degree of exclusionism and essentialism.[8][9]

【参考译文】政治学家卡斯·穆德认为,极右翼可以看作是四个广义概念的结合,即排他主义(例如种族主义、仇外心理、民族中心主义、民族多元主义、沙文主义,包括福利沙文主义)、反民主和非个人主义特征(例如个人崇拜、等级制度、一元论、民粹主义、反政党政治、有机主义的国家观)、哀叹历史参照框架消失的传统主义价值体系(例如法律和秩序、家庭、民族、语言和宗教社区和国家以及自然环境[7])和将社团主义、国家对某些部门的控制、农业主义和不同程度地相信社会达尔文主义市场力量的自由发挥联系起来的社会经济计划。随后,穆德根据排他主义和本质主义的程度,将极右翼星云细分为温和派和激进派。[8][9]

1.2 定义与比较分析 | Definition and comparative analysis

The Encyclopedia of Politics: The Left and the Right states that far-right politics include “persons or groups who hold extreme nationalist, xenophobic, homophobic, racist, religious fundamentalist, or other reactionary views.” While the term far right is typically applied to fascists and neo-Nazis, it has also been used to refer to those to the right of mainstream right-wing politics.[10]

【参考译文】《政治百科全书:左翼与右翼》指出,极右翼政治包括“持有极端民族主义、仇外主义、恐同主义、种族主义、宗教原教旨主义或其他反动观点的个人或团体”。虽然极右翼一词通常适用于法西斯分子和新纳粹分子,但它也被用来指代主流右翼政治的右侧人士。[10]

According to political scientist Lubomír Kopeček, “[t]he best working definition of the contemporary far right may be the four-element combination of nationalism, xenophobia, law and order, and welfare chauvinism proposed for the Western European environment by Cas Mudde.”[11] Relying on those concepts, far-right politics includes yet is not limited to aspects of authoritarianism, anti-communism[11] and nativism.[12] Claims that superior people should have greater rights than inferior people are often associated with the far right, as they have historically favored a social Darwinistic or elitist hierarchy based on the belief in the legitimacy of the rule of a supposed superior minority over the inferior masses.[13] Regarding the socio-cultural dimension of nationality, culture and migration, one far-right position is the view that certain ethnic, racial or religious groups should stay separate, based on the belief that the interests of one’s own group should be prioritized.[14]

【参考译文】政治学家卢博米尔·科佩切克认为,“当代极右翼的最佳定义可能是卡斯·穆德为西欧环境提出的民族主义、仇外心理、法律和秩序以及福利沙文主义四要素组合”。[11] 依据这些概念,极右翼政治包括但不限于威权主义、反共产主义[11] 和本土主义[12] 等方面。极右翼经常声称优等生应该比劣等生享有更大的权利,因为他们历来主张社会达尔文主义或精英主义等级制度,这种等级制度基于对所谓优等少数群体统治劣等大众的合法性的信仰。[13] 关于国籍、文化和移民的社会文化维度,极右翼的一种立场是,某些族裔、种族或宗教群体应该保持独立,因为他们相信应该优先考虑自己群体的利益。[14]

In western Europe, far right parties have been associated with anti-immigrant policies, as well as opposition to globalism and European integration. They often make nationalist and xenophobic appeals which make allusions to ethnic nationalism rather than civic nationalism (or liberal nationalism). Some have at their core illiberal policies such as removing checks on executive authority, and protections for minorities from majority (multipluralism). In the 1990s, the “winning formula” was often to attract anti-immigrant blue collar workers and white collar workers who wanted less state intervention in the economy, but in the 2000s, this switched to welfare chauvinism.[15]

【参考译文】在西欧,极右翼政党一直与反移民政策以及反对全球化和欧洲一体化有关。他们经常发表民族主义和仇外主义的呼吁,这些呼吁暗指民族主义而非公民民族主义(或自由民族主义)。有些政党的核心政策是非自由主义,例如取消对行政权力的制约,以及保护少数群体免受多数群体的侵害(多元主义)。在 1990 年代,“制胜法宝”通常是吸引反移民的蓝领工人和白领工人,他们希望国家减少对经济的干预,但在 2000 年代,这转向了福利沙文主义。[15]

In comparing the Western European and post-Communist Central European far-right, Kopeček writes that “[t]he Central European far right was also typified by a strong anti-Communism, much more markedly than in Western Europe”, allowing for “a basic ideological classification within a unified party family, despite the heterogeneity of the far right parties.” Kopeček concludes that a comparison of Central European far-right parties with those of Western Europe shows that “these four elements are present in Central Europe as well, though in a somewhat modified form, despite differing political, economic, and social influences.”[11] In the American and more general Anglo-Saxon environment, the most common term is “radical right“, which has a broader meaning than the European radical right.[16][11] Mudde defines the American radical right as an “old school of nativism, populism, and hostility to central government [which] was said to have developed into the post-World War II combination of ultranationalism and anti-communism, Christian fundamentalism, militaristic orientation, and anti-alien sentiment.”[16]

【参考译文】在比较西欧和后共产主义中欧极右翼时,科佩切克写道:“中欧极右翼也具有强烈的反共产主义特征,比西欧更为明显”,允许“在统一的政党家族中,尽管极右翼政党之间存在异质性,但存在基本的意识形态分类。” 科佩切克的结论是,将中欧极右翼政党与西欧极右翼政党进行比较,可以发现“这四个要素在中欧也存在,尽管形式略有修改,但政治、经济和社会影响不同。”[11] 在美国和更广泛的盎格鲁-撒克逊环境中,最常见的术语是“激进右翼”,其含义比欧洲激进右翼更广泛。[16][11]穆德将美国激进右翼定义为“本土主义、民粹主义和对中央政府的敌意的老派,据说在二战后发展成为极端民族主义和反共产主义、基督教原教旨主义、军国主义倾向和反外星人情绪的结合。”[16]

Jodi Dean argues that “the rise of far-right anti-communism in many parts of the world” should be interpreted “as a politics of fear, which utilizes the disaffection and anger generated by capitalism. […] Partisans of far right-wing organizations, in turn, use anti-communism to challenge every political current which is not embedded in a clearly exposed nationalist and racist agenda. For them, both the USSR and the European Union, leftist liberals, ecologists, and supranational corporations – all of these may be called ‘communist’ for the sake of their expediency.”[17]

【参考译文】乔迪·迪恩认为,“世界许多地方极右翼反共产主义的兴起”应该被解读为“一种恐惧政治,它利用了资本主义引发的不满和愤怒。[…] 极右翼组织的支持者则利用反共产主义来挑战每一种没有明确民族主义和种族主义议程的政治潮流。对他们来说,无论是苏联还是欧盟、左翼自由主义者、生态学家还是超国家公司——所有这些都可以为了方便而被称为‘共产主义’。”[17]

In Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right, Cynthia Miller-Idriss examines the far-right as a global movement and representing a cluster of overlapping “antidemocratic, antiegalitarian, white supremacist” beliefs that are “embedded in solutions like authoritarianism, ethnic cleansing or ethnic migration, and the establishment of separate ethno-states or enclaves along racial and ethnic lines”.[18]

【参考译文】在《祖国的仇恨:新的全球极右翼》一书中,辛西娅·米勒-伊德里斯将极右翼视为一场全球运动,代表了一组相互重叠的“反民主、反平等、白人至上主义”信仰,这些信仰“根植于独裁主义、种族清洗或族裔迁移等解决方案,以及建立沿着种族和族裔界限的独立民族国家或飞地”。[18]

2. 现代争论 | Modern debates

2.1 术语 | Terminology

According to Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg, the modern ambiguities in the definition of far-right politics lie in the fact that the concept is generally used by political adversaries to “disqualify and stigmatize all forms of partisan nationalism by reducing them to the historical experiments of Italian Fascism [and] German National Socialism.”[19] Mudde agrees and notes that “the term is not only used for scientific purposes but also for political purposes. Several authors define right-wing extremism as a sort of anti-thesis against their own beliefs.”[20] While the existence of such a political position is widely accepted among scholars, figures associated with the far-right rarely accept this denomination, preferring terms like “national movement” or “national right”.[19] There is also debate about how appropriate the labels neo-fascist or neo-Nazi are. In the words of Mudde, “the labels Neo-Nazi and to a lesser extent neo-Fascism are now used exclusively for parties and groups that explicitly state a desire to restore the Third Reich or quote historical National Socialism as their ideological influence.”[21]

【参考译文】根据让-伊夫·加缪 (Jean-Yves Camus) 和尼古拉斯·勒布尔 (Nicolas Lebourg) 的说法,现代极右翼政治定义中的模糊性在于,这一概念通常被政治对手用来“将所有形式的党派民族主义贬低为意大利法西斯主义和德国国家社会主义的历史实验,从而否定和污蔑它们”。[19] 穆德表示同意,并指出“该术语不仅用于科学目的,也用于政治目的。一些作者将右翼极端主义定义为与他们自己信仰相反的一种观点。”[20] 虽然学者们普遍接受这种政治立场的存在,但与极右翼有关的人物很少接受这一称呼,他们更喜欢使用“民族运动”或“民族右翼”等术语。[19] 关于新法西斯主义者或新纳粹分子的标签是否合适也存在争议。用穆德的话来说,“新纳粹主义和程度较小的新法西斯主义的标签,现在专门用于那些明确表示希望恢复第三帝国,或引用历史上的国家社会主义作为其意识形态影响的政党和团体。”[21]

One issue is whether parties should be labelled radical or extreme, a distinction that is made by the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany when determining whether or not a party should be banned.[nb 1] Within the broader family of the far right, the extreme right is revolutionary, opposing popular sovereignty and majority rule, and sometimes supporting violence, whereas the radical right is reformist, accepting free elections, but opposing fundamental elements of liberal democracy such as minority rights, rule of law, or separation of powers.[22]

【参考译文】一个问题是,政党是否应被贴上激进或极端的标签,这是德国联邦宪法法院在决定是否应禁止某个政党时所作的区分。[注、nb 1] 在极右翼的大家庭中,极右翼是革命性的,反对人民主权和多数人统治,有时支持暴力;而激进右翼是改革派,接受自由选举,但反对自由民主的基本要素,如少数人权利、法治或三权分立。[22]

【nb1 注释】Mudde 2002, p. 12: “Simply stated, the difference between radicalism and extremism is that the former is verfassungswidrig (opposed to the constitution), whereas the latter is verfassungsfeindlich (hostile towards the constitution). This difference is of the utmost practical importance for the political parties involved, as extremist parties are extensively watched by the (federal and state) Verfassungsschutz and can even be banned, whereas radical parties are free from this control.”

【参考译文】Mudde 2002,第 12 页:“简单地说,激进主义和极端主义的区别在于,前者是 verfassungswidrig(反对宪法),而后者是 verfassungsfeindlich(敌视宪法)。这一区别对于相关政党而言具有极为重要的实际意义,因为极端主义政党受到(联邦和州)宪法保卫局的严格监视,甚至可能被取缔,而激进政党则不受这种控制。”

After a survey of the academic literature, Mudde concluded in 2002 that the terms “right-wing extremism”, “right-wing populism“, “national populism”, or “neo-populism” were often used as synonyms by scholars (or, nonetheless, terms with “striking similarities”), except notably among a few authors studying the extremist-theoretical tradition.[nb 2]

【参考译文】在对学术文献进行调查后,穆德于 2002 年得出结论,“右翼极端主义”、“右翼民粹主义”、“民族民粹主义”或“新民粹主义”这些术语经常被学者用作同义词(或具有“惊人相似性”的术语),但研究极端主义理论传统的少数作者除外。[nb 2]

【nb 2注释】Mudde 2002, p. 13: “All in all, most definitions of (whatever) populism do not differ that much in content from the definitions of right-wing extremism. […] When the whole range of different terms and definitions used in the field is surveyed, there are striking similarities, with the various terms often being used synonymously and without any clear intention. Only a few authors, most notably those working within the extremist-theoretical tradition, clearly distinguish between the various terms.”

【参考译文】Mudde 2002,第 13 页:“总而言之,大多数民粹主义的定义在内容上与右翼极端主义的定义并没有太大区别。[…] 当对该领域使用的各种不同术语和定义进行调查时,会发现惊人的相似之处,各种术语经常被同义使用,没有任何明确的意图。只有少数作者,尤其是那些在极端主义理论传统中工作的作者,清楚地区分了各种术语。”

2.2 与右翼的关系 | Relation to right-wing politics

Italian philosopher and political scientist Norberto Bobbio argues that attitudes towards equality are primarily what distinguish left-wing politics from right-wing politics on the political spectrum:[23] “the left considers the key inequalities between people to be artificial and negative, which should be overcome by an active state, whereas the right believes that inequalities between people are natural and positive, and should be either defended or left alone by the state.”[24]

【参考译文】意大利哲学家、政治学家诺贝托·博比奥 (Norberto Bobbio) 认为,对平等的态度是政治光谱上左翼政治与右翼政治的主要区别:[23]“左翼认为人与人之间主要的不平等是人为的、消极的,应由积极的国家来克服;而右翼则认为人与人之间的不平等是自然的、积极的,国家应该予以捍卫或放任不管。”[24]

Aspects of far-right ideology can be identified in the agenda of some contemporary right-wing parties: in particular, the idea that superior persons should dominate society while undesirable elements should be purged, which in extreme cases has resulted in genocides.[25] Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform in London, distinguishes between fascism and right-wing nationalist parties which are often described as far right such as the National Front in France.[26] Mudde notes that the most successful European far-right parties in 2019 were “former mainstream right-wing parties that have turned into populist radical right ones.”[27] According to historian Mark Sedgwick, “[t]here is no general agreement as to where the mainstream ends and the extreme starts, and if there ever had been agreement on this, the recent shift in the mainstream would challenge it.”[28]

【参考译文】一些当代右翼政党的议程中可以看到极右翼意识形态的某些方面:特别是优越者应该统治社会,而不良分子应该被清除的想法,在极端情况下,这种想法导致了种族灭绝。[25] 伦敦欧洲改革中心主任查尔斯·格兰特 (Charles Grant) 将法西斯主义与右翼民族主义政党区分开来,后者通常被描述为极右翼,例如法国国民阵线。[26] 穆德指出,2019 年最成功的欧洲极右翼政党是“前主流右翼政党,现已转变为民粹主义极右翼政党”。[27] 根据历史学家马克·塞奇威克 (Mark Sedgwick) 的说法,“对于主流在哪里结束、极端在哪里开始,并没有普遍的共识,如果曾经就此达成过共识,那么最近主流的转变将对其提出挑战。”[28]

Proponents of the horseshoe theory interpretation of the left–right political spectrum identify the far left and the far right as having more in common with each other as extremists than each of them has with centrists or moderates.[29] This theory has received criticism,[30][31][32] including the argument that it has been centrists who have supported far-right and fascist regimes over socialist ones.[33]

【参考译文】马蹄铁理论对左右翼政治光谱的解释是,支持这一理论的人认为,极左翼和极右翼作为极端主义者,彼此之间的共同点比他们与中间派或温和派之间的共同点更多。[29] 这一理论受到了批评,[30][31][32] 包括有观点认为,中间派支持极右翼和法西斯政权,而非社会主义政权。[33]

Nature of support

Jens Rydgren describes a number of theories as to why individuals support far-right political parties and the academic literature on this topic distinguishes between demand-side theories that have changed the “interests, emotions, attitudes and preferences of voters” and supply-side theories which focus on the programmes of parties, their organization and the opportunity structures within individual political systems.[34] The most common demand-side theories are the social breakdown thesis, the relative deprivation thesis, the modernization losers thesis and the ethnic competition thesis.[35]

【参考译文】延斯·吕德格伦 (Jens Rydgren) 介绍了多种理论来解释个人为何支持极右翼政党,有关该主题的学术文献将需求方理论与供给方理论区分开来。需求方理论改变了“选民的利益、情感、态度和偏好”,而供给方理论则关注政党的纲领、组织和各个政治体系中的机会结构。[34] 最常见的需求方理论是社会崩溃论、相对剥夺论、现代化失败者论和种族竞争论。[35]

The rise of far-right parties has also been viewed as a rejection of post-materialist values on the part of some voters. This theory which is known as the reverse post-material thesis blames both left-wing and progressive parties for embracing a post-material agenda (including feminism and environmentalism) that alienates traditional working class voters.[36][37] Another study argues that individuals who join far-right parties determine whether those parties develop into major political players or whether they remain marginalized.[38]

【参考译文】极右翼政党的崛起也被视为部分选民对后物质主义价值观的拒绝。这一理论被称为“后物质主义的反向论题”,指责左翼和进步党派拥护后物质主义议程(包括女权主义和环保主义),疏远了传统的工人阶级选民。[36][37] 另一项研究认为,加入极右翼政党的个人决定了这些政党是发展成为主要政治参与者还是继续被边缘化。[38]

Early academic studies adopted psychoanalytical explanations for the far right’s support. The 1933 publication The Mass Psychology of Fascism by Wilhelm Reich argued the theory that fascists came to power in Germany as a result of sexual repression. For some far-right parties in Western Europe, the issue of immigration has become the dominant issue among them, so much so that some scholars refer to these parties as “anti-immigrant” parties.[39]

【参考译文】早期学术研究采用心理分析来解释极右翼的支持。威廉·赖希在 1933 年出版的《法西斯主义的大众心理学》提出了这样的理论:法西斯分子在德国掌权是因为性压抑。对于西欧的一些极右翼政党来说,移民问题已成为他们之间的主导问题,以至于一些学者将这些政党称为“反移民”政党。[39]

3. 思想史 | Intellectual history

3.1 背景 | Background

The French Revolution in 1789 created a major shift in political thought by challenging the established ideas supporting hierarchy with new ones about universal equality and freedom.[40] The modern left–right political spectrum also emerged during this period. Democrats and proponents of universal suffrage were located on the left side of the elected French Assembly, while monarchists seated farthest to the right.[19]

【参考译文】1789 年的法国大革命引发了政治思想的重大转变,它用关于普遍平等和自由的新思想挑战了支持等级制度的既定思想。[40] 现代左右翼政治光谱也在这一时期出现。民主党人和普选权的支持者位于法国民选议会的左侧,而君主主义者则坐在最右边。[19]

The strongest opponents of liberalism and democracy during the 19th century, such as Joseph de Maistre and Friedrich Nietzsche, were highly critical of the French Revolution.[41] Those who advocated a return to the absolute monarchy during the 19th century called themselves “ultra-monarchists” and embraced a “mystic” and “providentialist” vision of the world where royal dynasties were seen as the “repositories of divine will”. The opposition to liberal modernity was based on the belief that hierarchy and rootedness are more important than equality and liberty, with the latter two being dehumanizing.[42]

【参考译文】19 世纪自由主义和民主的最强烈反对者,如约瑟夫·德·迈斯特和弗里德里希·尼采,对法国大革命持强烈批评态度。[41] 那些主张在 19 世纪恢复绝对君主制的人自称是“极端君主主义者”,他们信奉“神秘主义”和“天意主义”的世界观,认为王朝是“神意的宝库”。反对自由现代性是基于这样的信念:等级制度和根基比平等和自由更重要,后两者是不人道的。[42]

3.2 生成 | Emergence

图片题注:Leon Trotsky was an early observer on the rise of far-right phenomenon such as Nazi Germany during his final years in exile[43] and advocated for the tactic of a united front.[44]

参考译文:列夫·托洛茨基在流亡的最后几年里,早期观察了纳粹德国等极右翼现象的崛起[43],并主张统一战线的策略。[44]

In the French public debate following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, far right was used to describe the strongest opponents of the far left, those who supported the events occurring in Russia.[5] A number of thinkers on the far right nonetheless claimed an influence from an anti-Marxist and anti-egalitarian interpretation of socialism, based on a military comradeship that rejected Marxist class analysis, or what Oswald Spengler had called a “socialism of the blood”, which is sometimes described by scholars as a form of “socialist revisionism“.[45] They included Charles Maurras, Benito Mussolini, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Ernst Niekisch.[46][47][48] Those thinkers eventually split along nationalist lines from the original communist movement, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels contradicting nationalist theories with the idea that “the working men [had] no country.”[49] The main reason for that ideological confusion can be found in the consequences of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, which according to Swiss historian Philippe Burrin had completely redesigned the political landscape in Europe by diffusing the idea of an anti-individualistic concept of “national unity” rising above the right and left division.[48]

【参考译文】在 1917 年布尔什维克革命后的法国公开辩论中,极右翼被用来形容极左翼最强烈的反对者,即那些支持俄国正在发生的事件的人。[5] 尽管如此,一些极右翼思想家声称自己受到了反马克思主义和反平等主义的社会主义解读的影响,这种解读基于拒绝马克思主义阶级分析的军事情谊,或奥斯瓦尔德·斯宾格勒所说的“血腥社会主义”,学者们有时将其描述为一种“社会主义修正主义”。[45] 其中包括夏尔·莫拉斯、贝尼托·墨索里尼、亚瑟·莫勒·范登布鲁克和恩斯特·尼基施。[46][47][48]这些思想家最终沿着民族主义的路线与最初的共产主义运动分道扬镳,卡尔·马克思和弗里德里希·恩格斯用“工人没有国家”的观点来反驳民族主义理论。[49] 这种意识形态混乱的主要原因可以追溯到 1870 年普法战争的后果,根据瑞士历史学家菲利普·伯林的说法,这场战争通过传播一种超越左右两翼分歧的反个人主义“民族团结”概念,彻底改变了欧洲的政治格局。[48]

As the concept of “the masses” was introduced into the political debate through industrialization and the universal suffrage, a new right-wing founded on national and social ideas began to emerge, what Zeev Sternhell has called the “revolutionary right” and a foreshadowing of fascism. The rift between the left and nationalists was furthermore accentuated by the emergence of anti-militarist and anti-patriotic movements like anarchism or syndicalism, which shared even fewer similarities with the far right.[49] The latter began to develop a “nationalist mysticism” entirely different from that on the left, and antisemitism turned into a credo of the far right, marking a break from the traditional economic “anti-Judaism” defended by parts of the far left, in favour of a racial and pseudo-scientific notion of alterity. Various nationalist leagues began to form across Europe like the Pan-German League or the Ligue des Patriotes, with the common goal of a uniting the masses beyond social divisions.[50][51]

【参考译文】随着“群众”的概念通过工业化和普选被引入政治辩论,一个以民族和社会理念为基础的新右翼开始出现,泽夫·斯特恩赫尔称之为“革命右翼”,是法西斯主义的预兆。左翼与民族主义者之间的裂痕因无政府主义或工团主义等反军国主义和反爱国主义运动的出现而进一步加剧,这些运动与极右翼几乎没有相似之处。[49] 后者开始发展一种与左翼完全不同的“民族主义神秘主义”,反犹太主义成为极右翼的信条,标志着极右翼与部分极左翼所捍卫的传统经济“反犹太主义”决裂,转而支持种族主义和伪科学的他性概念。欧洲各地开始形成各种民族主义联盟,如泛德联盟或爱国者联盟,其共同目标是团结超越社会分歧的群众。[50][51]

3.3 民族主义和革命右翼 | Völkisch and revolutionary right

图片题注:Spanish Falangist volunteer forces of the Blue Division entrain at San Sebastián, 1942

参考译文:1942 年,西班牙法西斯党志愿部队蓝色师团在圣塞巴斯蒂安登车

图片来源:Pascual Marín

The Völkisch movement emerged in the late 19th century, drawing inspiration from German Romanticism and its fascination for a medieval Reich supposedly organized into a harmonious hierarchical order. Erected on the idea of “blood and soil“, it was a racialist, populist, agrarian, romantic nationalist and an antisemitic movement from the 1900s onward as a consequence of a growing exclusive and racial connotation.[52] They idealized the myth of an “original nation”, that still could be found at their times in the rural regions of Germany, a form of “primitive democracy freely subjected to their natural elites.”[47] Thinkers led by Arthur de Gobineau, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Alexis Carrel and Georges Vacher de Lapouge distorted Darwin‘s theory of evolution to advocate a “race struggle” and an hygienist vision of the world. The purity of the bio-mystical and primordial nation theorized by the Völkischen then began to be seen as corrupted by foreign elements, Jewish in particular.[52]

【参考译文】民族主义运动兴起于 19 世纪末,其灵感来自德国浪漫主义,以及对中世纪帝国的迷恋,该帝国据称组织成一个和谐的等级秩序。民族主义运动建立在“血与土”的理念之上,是一场种族主义、民粹主义、农业主义、浪漫民族主义和反犹太主义运动,自 20 世纪初以来,由于排他性和种族内涵的日益加深而发展起来。[52] 他们理想化了“原始民族”的神话,这种神话在当时的德国农村地区仍然可以找到,是一种“自由地服从于自然精英的原始民主”。[47] 以阿瑟·戈比诺、休斯顿·斯图尔特·张伯伦、亚历克西斯·卡雷尔和乔治斯·瓦谢·德·拉普格为首的思想家歪曲了达尔文的进化论,提倡“种族斗争”和卫生主义的世界观。民族主义者理论中的生物神秘主义和原始民族的纯洁性开始被视为受到外来因素(尤其是犹太人)的腐蚀。[52]

Translated in Maurice Barrès‘ concept of “the earth and the dead”, these ideas influenced the pre-fascist “revolutionary right” across Europe. The latter had its origin in the fin de siècle intellectual crisis and it was, in the words of Fritz Stern, the deep “cultural despair” of thinkers feeling uprooted within the rationalism and scientism of the modern world.[53] It was characterized by a rejection of the established social order, with revolutionary tendencies and anti-capitalist stances, a populist and plebiscitary dimension, the advocacy of violence as a means of action and a call for individual and collective palingenesis (“regeneration, rebirth”).[54]

【参考译文】这些思想被转化成莫里斯·巴雷斯的“大地与死者”概念,影响了整个欧洲前法西斯主义的“革命右翼”。后者起源于世纪末的知识危机,用弗里茨·斯特恩的话来说,这是思想家在现代世界的理性主义和科学主义中感到被连根拔起的深刻“文化绝望”。[53] 它的特点是拒绝既定的社会秩序,具有革命倾向和反资本主义立场,具有民粹主义和公民投票的维度,提倡以暴力为行动手段,呼吁个人和集体的再生(“再生、重生”)。[54]

3.4 当代思想 | Contemporary thought

The key thinkers of contemporary far-right politics are claimed by Mark Sedgwick to share four key elements, namely apocalyptism, fear of global elites, belief in Carl Schmitt‘s friend–enemy distinction and the idea of metapolitics.[55] The apocalyptic strain of thought begins in Oswald Spengler‘s The Decline of the West and is shared by Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist. It continues in The Death of the West by Pat Buchanan as well as in fears over Islamization of Europe.[55] Ernst Jünger was concerned about rootless cosmopolitan elites while de Benoist and Buchanan oppose the managerial state and Curtis Yarvin is against “the Cathedral”.[55] Schmitt’s friend–enemy distinction has inspired the French Nouvelle Droite idea of ethnopluralism.[55]

【参考译文】马克·塞奇威克认为,当代极右翼政治的主要思想家具有四个共同的关键要素,即末世论、对全球精英的恐惧、对卡尔·施密特敌友区分的信仰以及元政治思想。[55] 末世论思想始于奥斯瓦尔德·斯宾格勒的《西方的没落》,尤利乌斯·埃沃拉和阿兰·德·贝诺伊斯特也持有这种思想。这种思想延续到了帕特·布坎南的《西方之死》以及对欧洲伊斯兰化的恐惧中。[55] 恩斯特·荣格担心无根的世界主义精英,而德·贝诺伊斯特和布坎南反对管理国家,柯蒂斯·雅文反对“大教堂”。[55] 施密特的敌友区分启发了法国新右派的民族多元主义思想。[55]

图片题注:CasaPound rally in Naples

参考译文:CasaPound 在那不勒斯举行集会

图片来源:Cassatonante

In a 1961 book deemed influential in the European far-right at large, French neo-fascist writer Maurice Bardèche introduced the idea that fascism could survive the 20th century under a new metapolitical guise adapted to the changes of the times. Rather than trying to revive doomed regimes with their single party, secret police or public display of Caesarism, Bardèche argued that its theorists should promote the core philosophical idea of fascism regardless of its framework,[6] i.e. the concept that only a minority, “the physically saner, the morally purer, the most conscious of national interest”, can represent best the community and serve the less gifted in what Bardèche calls a new “feudal contract”.[56]

【参考译文】1961 年,法国新法西斯主义作家莫里斯·巴代什 (Maurice Bardèche) 出版了一本在欧洲极右翼中颇具影响力的书,书中提出了这样一种观点:法西斯主义可以在适应时代变化的新元政治幌子下在 20 世纪生存下来。巴代什认为,法西斯主义的理论家不应该试图通过单一政党、秘密警察或公开展示凯撒主义来复兴注定要失败的政权,而应该推广法西斯主义的核心哲学思想,而不管其框架如何,[6] 即只有少数人,“身体更健康、道德更纯洁、最有国家利益意识的人”,才能最好地代表社区,为天赋较差的人服务,这就是巴代什所说的新的“封建契约”。[56]

Another influence on contemporary far-right thought has been the Traditionalist School, which included Julius Evola, and has influenced Steve Bannon and Aleksandr Dugin, advisors to Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin as well as the Jobbik party in Hungary.[57]

【参考译文】传统主义学派也是当代极右翼思想的一个影响因素,该学派包括尤利乌斯·埃沃拉 (Julius Evola),并影响了唐纳德·特朗普 (Donald Trump) 和弗拉基米尔·普京 (Vladimir Putin) 的顾问史蒂夫·班农 (Steve Bannon) 和亚历山大·杜金 (Aleksandr Dugin),以及匈牙利的 Jobbik 党。[57]

4. 国际组织 | International organizations

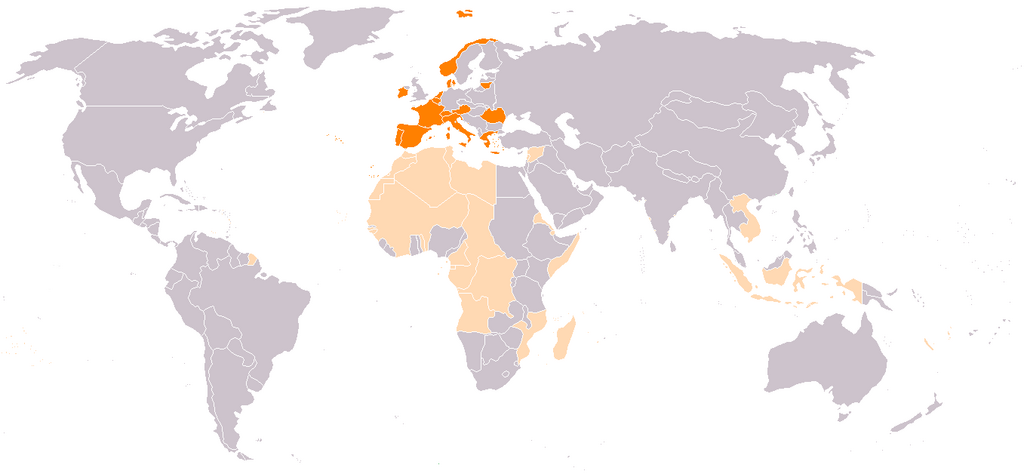

图片题注:National origins of Fascist International Congress participants in 1934

参考译文:1934 年法西斯国际代表大会与会者的国籍

图片来源:Apollodoro at Italian Wikipedia

During the rise of Nazi Germany, far-right international organizations began to emerge in the 1930s with the International Conference of Fascist Parties in 1932 and the Fascist International Congress in 1934.[58] During the 1934 Fascist International Conference, the Comitati d’Azione per l’Universalità di Roma [it] (CAUR; English: Action Committees for the Universality of Rome), created by Benito Mussolini‘s Fascist Regime to create a network for a “Fascist International”, representatives from far-right groups gathered in Montreux, Switzerland, including Romania‘s Iron Guard, Norway‘s Nasjonal Samling, the Greek National Socialist Party, Spain‘s Falange movement, Ireland’s Blueshirts, France‘s Mouvement Franciste and Portugal‘s União Nacional, among others.[59][60] However, no international group was fully established before the outbreak of World War II.[58]

【参考译文】在纳粹德国崛起期间,20世纪30年代开始涌现出极右翼国际组织,其中包括1932年的法西斯政党国际会议和1934年的法西斯国际大会。[58]在1934年的法西斯国际大会上,由贝尼托·墨索里尼的法西斯政权创立的行动委员会旨在建立一个“法西斯国际”网络,即罗马普遍性行动委员会(CAUR),来自极右翼团体的代表在瑞士蒙特勒聚集,其中包括罗马尼亚的铁卫军、挪威的民族统一党、希腊民族社会主义党、西班牙的法朗运动、爱尔兰的蓝衫军、法国的法兰西民族运动以及葡萄牙的国家联盟等。[59][60]然而,在第二次世界大战爆发前,没有任何国际组织得以完全建立。[58]

Following World War II, other far-right organizations attempted to establish themselves, such as the European organizations of Nouvel Ordre Européen, European Social Movement and Circulo Español de Amigos de Europa or the further-reaching World Union of National Socialists and the League for Pan-Nordic Friendship.[61] Beginning in the 1980s, far-right groups began to solidify themselves through official political avenues.[61]

【参考译文】第二次世界大战后,其他极右翼组织也试图建立自己的组织,如欧洲的新欧洲秩序组织、欧洲社会运动、西班牙欧洲之友圈,以及影响力更大的世界国家社会主义者联盟和泛北欧友谊联盟。[61]从20世纪80年代开始,极右翼团体开始通过官方政治途径巩固自己的地位。[61]

With the founding of the European Union in 1993, far-right groups began to espouse Euroscepticism, nationalist and anti-migrant beliefs.[58] By 2010, the Eurosceptic group European Alliance for Freedom emerged and saw some prominence during the 2014 European Parliament election.[58][61] The majority of far-right groups in the 2010s began to establish international contacts with right-wing coalitions to develop a solidified platform.[58] In 2017, Steve Bannon would create The Movement, an organization to create an international far-right group based on Aleksandr Dugin‘s The Fourth Political Theory, for the 2019 European Parliament election.[62][63] The European Alliance for Freedom would also reorganize into Identity and Democracy for the 2019 European Parliament election.[61]

【参考译文】随着1993年欧洲联盟的成立,极右翼团体开始宣扬疑欧主义、民族主义以及反移民的信仰。[58]到2010年,疑欧派团体“欧洲自由联盟”崭露头角,并在2014年欧洲议会选举期间获得了一定的关注度。[58][61]2010年代,大多数极右翼团体开始与右翼联盟建立国际联系,以发展一个稳固的平台。[58]2017年,史蒂夫·班农为2019年欧洲议会选举创建了“运动”组织,该组织旨在基于亚历山大·杜金的“第四政治理论”建立一个国际极右翼团体。[62][63]“欧洲自由联盟”也在为2019年欧洲议会选举做准备的过程中重组为“身份与民主”团体。[61]

The far-right Spanish party Vox initially introduced the Madrid Charter project, a planned group to denounce left-wing groups in Ibero-America, to the government of United States president Donald Trump while visiting the United States in February 2019, with Santiago Abascal and Rafael Bardají using their good relations with the administration to build support within the Republican Party and establishing strong ties with American contacts.[63][64][65] In March 2019, Abascal tweeted an image of himself wearing a morion similar to a conquistador, with ABC writing in an article detailing the document that this event provided a narrative that “symbolizes in part the expansionist mood of Vox and its ideology far from Spain”.[66] The charter subsequently grew to include signers that had little to no relation to Latin America and Spanish-speaking areas.[67] Vox has advised Javier Milei in Argentina, the Bolsonaro family in Brazil, José Antonio Kast in Chile and Keiko Fujimori in Peru.[68]

【参考译文】2019年2月,极右翼西班牙政党“声音党”在访问美国期间,向时任美国总统特朗普的政府提出了《马德里宪章》项目,该项目计划谴责伊比利亚美洲的左翼团体。圣地亚哥·阿巴斯卡尔和拉斐尔·巴尔达吉利用他们与美国政府之间的良好关系,在共和党内部建立支持,并与美国的联系人建立了牢固的关系。[63][64][65]2019年3月,阿巴斯卡尔在推特上发布了一张自己戴着类似征服者所戴的莫里恩头盔的照片,《ABC报》在一篇详细介绍该文件的文章中写道,这一事件“部分象征着声音党的扩张情绪及其远离西班牙的意识形态”。[66]随后,《宪章》的签署者队伍不断扩大,其中一些人与拉丁美洲和西班牙语地区几乎没有或根本没有关系。[67]声音党为阿根廷的哈维尔·米莱、巴西的博索纳罗家族、智利的何塞·安东尼奥·卡斯特和秘鲁的芙吉香里·藤森提供了建议。[68]

Nationalists from Europe and the United States met at a Holiday Inn in St. Petersburg on March 22, 2015, for first convention of the International Russian Conservative Forum organized by pro-Putin Rodina-party. The event was attended by fringe right-wing extremists like Nordic Resistance Movement from Scandinavia but also by more mainstream MEPs from Golden Dawn and National Democratic Party of Germany. In addition to Rodina, Russian neo-Nazis from Russian Imperial Movement and Rusich Group were also in attendance. From the US the event was attended by Jared Taylor and Brandon Russell.[69][70][71][72][73]

【参考译文】2015年3月22日,来自欧洲和美国的民族主义者齐聚圣彼得堡的一家假日酒店,参加由亲普京的“祖国党”组织的首届国际俄罗斯保守论坛。出席此次活动的有北欧抵抗运动等边缘右翼极端分子,也有来自希腊金色黎明党和德国国家民主党等更主流的成员。除了“祖国党”外,来自俄罗斯帝国运动和鲁斯奇集团的俄罗斯新纳粹分子也出席了会议。来自美国的参与者包括杰瑞德·泰勒和布兰登·罗素。[69][70][71][72][73]

5. 在各国的历史 | History by country

5.1 非洲 | Africa

5.1.1 摩洛哥 | Morocco

Morocco saw a spread of ultranationalism, antifeminism, and opposition to immigration themes in digital spaces.[74]

【参考译文】摩洛哥的数字空间出现了极端民族主义、反女权主义和反对移民主题的蔓延。[74]

5.1.2 卢旺达 | Rwanda

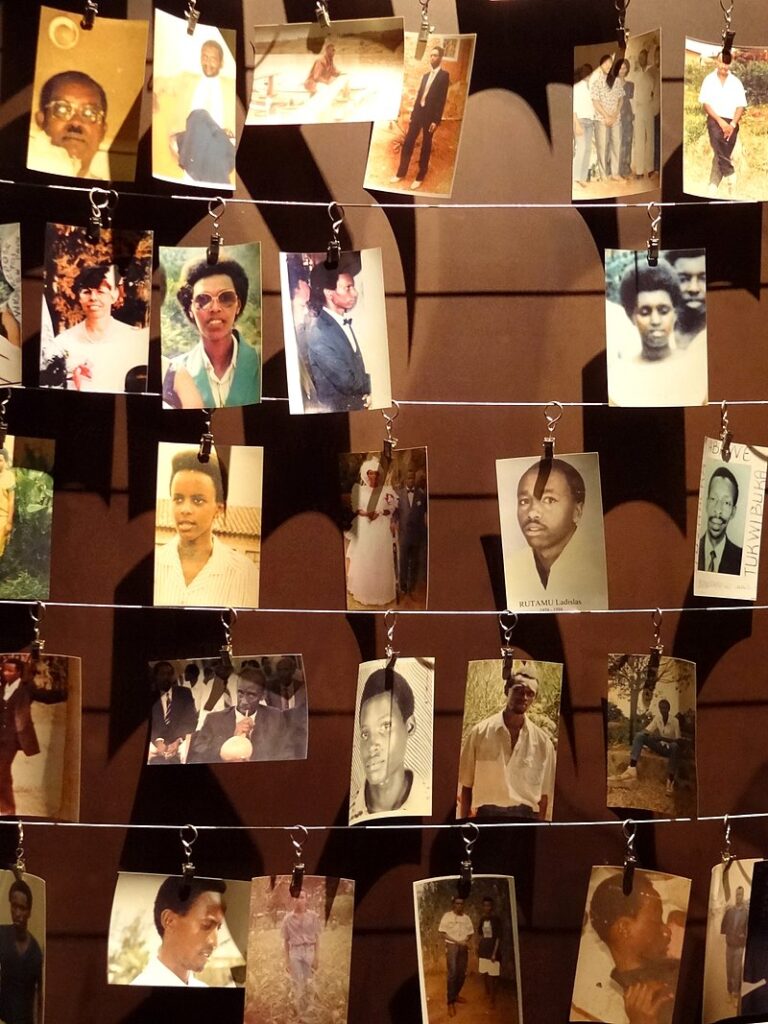

图片题注:Photographs of genocide victims displayed at the Genocide Memorial Center in Kigali

参考译文:基加利种族灭绝纪念中心展出的种族灭绝受害者照片

图片来源:Adam Jones, Ph.D

A number of far-right extremist and paramilitary groups carried out the Rwandan genocide under the racial supremacist ideology of Hutu Power, developed by journalist and Hutu supremacist Hassan Ngeze.[75] On 5 July 1975, exactly two years after the 1973 Rwandan coup d’état, the far right National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND) was founded under president Juvénal Habyarimana. Between 1975 and 1991, the MRND was the only legal political party in the country. It was dominated by Hutus, particularly from Habyarimana’s home region of Northern Rwanda. An elite group of MRND party members who were known to have influence on the President and his wife Agathe Habyarimana are known as the akazu, an informal organization of Hutu extremists whose members planned and lead the 1994 Rwandan genocide.[76][77] Prominent Hutu businessman and member of the akazu, Félicien Kabuga was one of the genocides main financiers, providing thousands of machetes which were used to commit the genocide.[78] Kabuga also founded Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, used to broadcast propaganda and direct the génocidaires. Kabuga was arrested in France on 16 May 2020, and charged with crimes against humanity.[79]

【参考译文】在记者兼胡图族至上主义者哈桑·恩杰泽提出的胡图族权力种族至上主义意识形态下,一些极右翼极端主义分子和准军事组织实施了卢旺达种族屠杀。[75]1975年7月5日,即在1973年卢旺达政变两年后,极右翼的民主与发展全国共和运动(MRND)在总统朱韦纳尔·哈比亚利马纳的领导下成立。1975年至1991年间,MRND是该国唯一的合法政党。该政党由胡图族人主导,尤其是来自哈比亚利马纳家乡卢旺达北部的胡图族人。MRND政党内部有一个精英团体,被称为“阿卡祖”,他们对总统及其妻子阿加莎·哈比亚利马纳有很大影响力。阿卡祖是一个由胡图族极端分子组成的非正式组织,其成员策划并领导了1994年的卢旺达种族屠杀。[76][77]著名的胡图族商人兼阿卡祖成员费利西安·卡布加是种族屠杀的主要资助者之一,他提供了数千把用于实施种族屠杀的马切特刀。[78]卡布加还创办了自由千山广播电台,用于传播宣传和指挥种族屠杀者。2020年5月16日,卡布加在法国被捕,并被控反人类罪。[79]

(1)伊图拉穆韦 | Interahamwe

Main article: Interahamwe【主条目:伊图拉穆韦】

The Interahamwe was formed around 1990 as the youth wing of the MRND and enjoyed the backing of the Hutu Power government. The Interahamwe were driven out of Rwanda after Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front victory in the Rwandan Civil War in July 1994 and are considered a terrorist organisation by many African and Western governments. The Interahamwe and splinter groups such as the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda continue to wage an insurgency against Rwanda from neighboring countries, where they are also involved in local conflicts and terrorism. The Interahamwe were the main perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide, during which an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 Tutsi, Twa and moderate Hutus were killed from April to July 1994 and the term Interahamwe was widened to mean any civilian bands killing Tutsi.[80][81]

【参考译文】伊图拉穆韦大约于1990年成立,是民主与发展全国共和运动(MRND)的青年组织,并得到了胡图族权力政府的支持。1994年7月,图西族领导的卢旺达爱国阵线在卢旺达内战中取得胜利后,伊图拉穆韦被驱逐出卢旺达,并被许多非洲和西方国家政府视为恐怖组织。伊图拉穆韦及其分裂组织,如解放卢旺达民主力量,继续从邻国对卢旺达发动叛乱,同时参与当地冲突和恐怖主义活动。伊图拉穆韦是卢旺达种族屠杀的主要肇事者,在1994年4月至7月期间,估计有50万至100万图西人、特瓦人和温和的胡图人被杀害,伊图拉穆韦一词也被泛指为杀害图西人的任何平民团伙。[80][81]

(2)保卫共和国联盟 | Coalition for the Defence of the Republic

Main article: Coalition for the Defence of the Republic【主条目:保卫共和国联盟】

Other far-right groups and paramilitaries involved included the anti-democratic segregationist Coalition for the Defence of the Republic (CDR), which called for complete segregation of Hutus from Tutsis. The CDR had a paramilitary wing known as the Impuzamugambi. Together with the Interahamwe militia, the Impuzamugambi played a central role in the Rwandan genocide.[82][75]

【参考译文】

其他参与的极右翼团体和准军事组织包括反民主的种族隔离主义组织保卫共和国联盟(CDR),该组织呼吁将胡图人与图西人完全隔离。保卫共和国联盟有一个准军事组织,被称为“Impuzamugambi”。Impuzamugambi与伊图拉穆韦民兵一起,在卢旺达种族屠杀中发挥了核心作用。[82][75]

5.1.3 南非 | South Africa

(1)重建国家党 | Herstigte Nasionale Party

Main article: Herstigte Nasionale Party【主条目:重建国家党】

The far right in South Africa emerged as the Herstigte Nasionale Party (HNP) in 1969, formed by Albert Hertzog as breakaway from the predominant right-wing South African National Party, an Afrikaner ethno-nationalist party that implemented the racist, segregationist program of apartheid, the legal system of political, economic and social separation of the races intended to maintain and extend political and economic control of South Africa by the White minority.[83][84][85] The HNP was formed after the South African National Party re-established diplomatic relations with Malawi and legislated to allow Māori players and spectators to enter the country during the 1970 New Zealand rugby union team tour in South Africa.[86] The HNP advocated for a Calvinist, racially segregated and Afrikaans-speaking nation.[87]

【参考译文】南非极右翼政党“南非国民党”于 1969 年成立,由阿尔伯特·赫佐格从当时占主导地位的右翼政党南非民族党中分离出来。南非民族党是一个阿非利卡人民族主义政党,推行种族隔离政策,即在政治、经济和社会上对种族进行分离的法律制度,旨在维持和扩大白人少数群体对南非的政治和经济控制。[83][84][85] 南非国民党在与马拉维重建外交关系后成立,并立法允许毛利球员和观众在 1970 年新西兰橄榄球联盟队南非巡回赛期间入境。[86] 南非国民党主张建立一个加尔文主义、种族隔离和讲南非荷兰语的国家。[87]

(2)南非荷兰人抵抗运动 | Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging

Main article: Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging【主条目:南非荷兰人抵抗运动】

In 1973, Eugène Terre’Blanche, a former police officer founded the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (Afrikaner Resistance Movement), a South African neo-Nazi paramilitary organisation, often described as a white supremacist group.[88][89][90] Since its founding in 1973 by Eugène Terre’Blanche and six other far-right Afrikaners, it has been dedicated to secessionist Afrikaner nationalism and the creation of an independent Boer-Afrikaner republic in part of South Africa. During negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa in the early 1990s, the organization terrorized and killed black South Africans.[91]

【参考译文】1973 年,前警官尤金·特雷布兰奇 (Eugène Terre’Blanche) 创立了南非新纳粹准军事组织阿非利卡人抵抗运动 (Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging),该组织经常被描述为白人至上主义团体。[88][89][90] 自 1973 年尤金·特雷布兰奇和其他六名极右翼阿非利卡人创立以来,该组织一直致力于分离主义阿非利卡人民族主义和在南非部分地区建立独立的布尔-阿非利卡人共和国。在 1990 年代初结束南非种族隔离的谈判期间,该组织恐吓并杀害了南非黑人。[91]

5.1.4 多哥 | Togo

Main article: Human rights in Togo【主条目:多哥的人权】

Togo has been ruled by members of the Gnassingbé family and the far-right military dictatorship formerly known as the Rally of the Togolese People since 1969. Despite the legalisation of political parties in 1991 and the ratification of a democratic constitution in 1992, the regime continues to be regarded as oppressive. In 1993, the European Union cut off aid in reaction to the regime’s human-rights offenses. After’s Eyadema’s death in 2005, his son Faure Gnassingbe took over, then stood down and was re-elected in elections that were widely described as fraudulent and occasioned violence that resulted in as many as 600 deaths and the flight from Togo of 40,000 refugees.[92] In 2012, Faure Gnassingbe dissolved the RTP and created the Union for the Republic.[93][94][95]

【参考译文】多哥自 1969 年以来一直由纳辛贝家族成员和极右翼军事独裁政权统治,该政权前身为多哥人民联盟。尽管 1991 年政党合法化,1992 年批准了民主宪法,但该政权仍然被视为压迫性的。1993 年,欧盟因该政权侵犯人权而切断了援助。2005 年埃亚德马去世后,他的儿子福雷·纳辛贝接任,然后辞职并再次当选,但选举被广泛描述为欺诈并引发暴力事件,导致多达 600 人死亡,40,000 名难民逃离多哥。[92] 2012 年,福雷·纳辛贝解散了 RTP,并创建了共和国联盟。[93][94][95]

Throughout the reign of the Gnassingbé family, Togo has been extremely oppressive. According to a United States Department of State report based on conditions in 2010, human rights abuses are common and include “security force use of excessive force, including torture, which resulted in deaths and injuries; official impunity; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrests and detention; lengthy pretrial detention; executive influence over the judiciary; infringement of citizens’ privacy rights; restrictions on freedoms of press, assembly, and movement; official corruption; discrimination and violence against women; child abuse, including female genital mutilation (FGM), and sexual exploitation of children; regional and ethnic discrimination; trafficking in persons, especially women and children; societal discrimination against persons with disabilities; official and societal discrimination against homosexual persons; societal discrimination against persons with HIV; and forced labor, including by children.”[96]

【参考译文】在纳辛贝家族统治期间,多哥一直非常压抑。根据美国国务院基于 2010 年情况的报告,侵犯人权行为很常见,包括“安全部队过度使用武力,包括酷刑,导致人员伤亡;官员有罪不罚;监狱条件恶劣,危及生命;任意逮捕和拘留;长期审前拘留;行政部门对司法部门的影响;侵犯公民隐私权;限制新闻、集会和行动自由;官员腐败;歧视和暴力侵害妇女;虐待儿童,包括女性生殖器切割 (FGM) 和对儿童的性剥削;地区和种族歧视;贩卖人口,特别是妇女和儿童;社会歧视残疾人;官员和社会歧视同性恋者;社会歧视艾滋病毒感染者;强迫劳动,包括儿童劳动。”[96]

5.1.5 其他国家和地区

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

5.2 美洲 | Americas

See also: Fascism in North America and Fascism in South America

【另请参阅:北美法西斯主义和南美法西斯主义】

5.2.1 巴西 | Brazil

图片题注:Children make the Nazi salute in Presidente Bernardes, São Paulo, circa 1935.

参考译文:1935 年左右,圣保罗伯纳德斯总统府,孩子们行纳粹礼。

During the 1920s and 1930s, a local brand of religious fascism appeared known as Brazilian Integralism, coalescing around the party known as Brazilian Integralist Action. It adopted many characteristics of European fascist movements, including a green-shirted paramilitary organization with uniformed ranks, highly regimented street demonstrations and rhetoric against Marxism and liberalism.[97]

【参考译文】20世纪20年代和30年代,一种名为巴西整体主义(Brazilian Integralism)的地方宗教法西斯主义思潮出现,其以巴西整体主义行动党为中心。它采纳了许多欧洲法西斯运动的特点,包括身穿绿色衬衫的准军事组织,设有统一军衔,组织高度严谨的街头示威活动,以及反对马克思主义和自由主义的言论。[97]

Prior to World War II, the Nazi Party had been making and distributing propaganda among ethnic Germans in Brazil. The Nazi regime built close ties with Brazil through the estimated 100 thousand native Germans and 1 million German descendants living in Brazil at the time.[98] In 1928, the Brazilian section of the Nazi Party was founded in Timbó, Santa Catarina. This section reached 2,822 members and was the largest section of the Nazi Party outside Germany.[99][100] About 100 thousand born Germans and about one million descendants lived in Brazil at that time.[101]

【参考译文】在第二次世界大战爆发前,纳粹党一直在巴西的德裔人群中制作和传播宣传品。纳粹政权通过当时生活在巴西的约10万德国本土人和100万德国后裔,与巴西建立了密切联系。[98]1928年,纳粹党巴西支部在圣卡塔琳娜州的廷博成立。该支部拥有2822名成员,是纳粹党在德国以外最大的支部。[99][100]当时,巴西约有10万德裔出生者和约100万德裔后裔。[101]

After Germany’s defeat in World War II, many Nazi war criminals fled to Brazil and hid among the German-Brazilian communities. The most notable example of this was Josef Mengele, a Nazi SS officer and physician known as the “Angel of Death” for his deadly experiments on prisoners at the Auschwitz II (Birkenau) concentration camp, who fled first to Argentina, then Paraguay, before finally settling in Brazil in 1960. Mengele eventually drowned in 1979 in Bertioga, on the coast of São Paulo state, without ever having been recognized in his 19 years in Brazil.[102]

【参考译文】第二次世界大战德国战败后,许多纳粹战犯逃往巴西,并藏匿于德裔巴西人社区中。其中最著名的例子是纳粹党卫军军官兼医生约瑟夫·门格尔,他因在奥斯维辛二号(比克瑙)集中营对囚犯进行致命实验而被称为“死亡天使”。门格尔先是逃到阿根廷,再逃到巴拉圭,最后于1960年定居巴西。门格尔最终在1979年于圣保罗州的海滨城市贝尔蒂奥加溺水身亡,在巴西隐居的19年里,他的身份一直没有被识破。[102]

The far right has continued to operate throughout Brazil[103] and a number of far-right parties existed in the modern era including Patriota, the Brazilian Labour Renewal Party, the Party of the Reconstruction of the National Order, the National Renewal Alliance and the Social Liberal Party as well as death squads such as the Command for Hunting Communists. Former President of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro was a member of the Alliance for Brazil, a far-right nationalist political group that aimed to become a political party, until 2022, when the party was disbanded. Since 2022, he is a member of the Liberal Party.[104][105][106] Bolsonaro has been widely described by numerous media organizations as far right.[107]

【参考译文】极右翼势力一直在巴西活动[103],现代巴西存在着多个极右翼政党,包括爱国者党、巴西劳工复兴党、国家秩序重建党、国家复兴联盟和社会自由党,以及诸如“共产主义者猎杀突击队”等死亡小队。巴西前总统雅伊尔·博索纳罗曾是极右翼民族主义政治团体“巴西联盟”的成员,该团体旨在成为一个政党,直到2022年被解散。自2022年起,博索纳罗成为自由党成员。[104][105][106]多家媒体组织广泛认为博索纳罗是极右翼人士。[107]

5.2.2 危地马拉 | Guatemala

Main article: National Liberation Movement (Guatemala)【主条目:民族解放运动 (危地马拉)】

In Guatemala, the far-right[108][109] government of Carlos Castillo Armas utilized death squads after coming to power in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état.[108][109] Along with other far-right extremists, Castillo Armas started the National Liberation Movement (Movimiento de Liberación Nacional, or MLN). The founders of the party described it as the “party of organized violence”.[110] The new government promptly reversed the democratic reforms initiated during the Guatemalan Revolution and the agrarian reform program (Decree 900) that was the main project of president Jacobo Arbenz Guzman and which directly impacted the interests of both the United Fruit Company and the Guatemalan landowners.[111]

【参考译文】在危地马拉,极右翼[108][109]政府领导人卡洛斯·卡斯蒂略·阿马斯在1954年危地马拉政变上台后,动用了死亡小队。[108][109]卡斯蒂略·阿马斯与其他极右翼极端分子一起,创立了民族解放运动(西班牙语:Movimiento de Liberación Nacional,简称MLN)。该党的创始人将其描述为“有组织暴力的政党”。[110]新政府迅速推翻了危地马拉革命期间发起的民主改革和土地改革计划(第900号法令),这是雅各布·阿本斯·古兹曼总统的主要项目,直接影响了联合果品公司和危地马拉地主的利益。[111]

Mano Blanca, otherwise known as the Movement of Organized Nationalist Action, was set up in 1966 as a front for the MLN to carry out its more violent activities,[112][113] along with many other similar groups, including the New Anticommunist Organization and the Anticommunist Council of Guatemala.[110][114] Mano Blanca was active during the governments of colonel Carlos Arana Osorio and general Kjell Laugerud García and was dissolved by general Fernando Romeo Lucas Garcia in 1978.[115]

【参考译文】“白手运动”(Mano Blanca),又称有组织民族行动运动,于1966年成立,是MLN进行更暴力活动的前线组织,[112][113]以及其他许多类似组织,包括新反共组织和危地马拉反共理事会。[110][114]“白手运动”在卡洛斯·阿拉纳·奥索里奥上校和凯尔·劳格德·加西亚将军执政期间很活跃,1978年被费尔南多·罗密欧·卢卡斯·加西亚将军解散。[115]

Armed with the support and coordination of the Guatemalan Armed Forces, Mano Blanca began a campaign described by the United States Department of State as one of “kidnappings, torture, and summary execution.”[113] One of the main targets of Mano Blanca was the Revolutionary Party, an anti-communist group that was the only major reform oriented party allowed to operate under the military-dominated regime. Other targets included the banned leftist parties.[113] Human rights activist Blase Bonpane described the activities of Mano Blanca as being an integral part of the policy of the Guatemalan government and by extension the policy of the United States government and the Central Intelligence Agency.[111][116] Overall, Mano Blanca was responsible for thousands of murders and kidnappings, leading travel writer Paul Theroux to refer to them as “Guatemala’s version of a volunteer Gestapo unit”.[117]

【参考译文】在危地马拉武装部队的支持和协调下,“白手运动”开始了一场美国国务院描述为“绑架、酷刑和即决处决”的运动。[113]“白手运动”的主要目标之一是革命党,这是一个反共组织,也是军事独裁统治下唯一被允许运作的主要改革政党。其他目标还包括被禁止的左翼政党。[113]人权活动家布莱斯·邦潘认为,“白手运动”的活动是危地马拉政府政策不可或缺的一部分,进而也是美国政府和中央情报局政策的一部分。[111][116]总体而言,“白手运动”对数千起谋杀和绑架事件负有责任,旅游作家保罗·西罗克斯称之为“危地马拉版的志愿盖世太保部队”。[117]

5.2.3 智利 | Chile

图片题注:Dictator of Chile Augusto Pinochet meeting with United States President George H. W. Bush in 1990

参考译文:智利独裁者奥古斯托·皮诺切特于1990年会见美国总统乔治·H·W·布什

图片来源:Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile

The National Socialist Movement of Chile (MNSCH) was created in the 1930s with the funding from the German population in Chile.[118] In 1938, the MNSCH was dissolved after it attempted a coup and recreated itself as the Popular Freedom Alliance party, later merging with the Agrarian Party to create the Agrarian Labor Party (PAL).[119] PAL would go through various mergers to become the Partido Nacional Popular (Chile) [es], then National Action and finally the National Party.

【参考译文】智利民族社会主义运动(MNSCH)于20世纪30年代在智利德国人的资助下创立。[118]1938年,MNSCH在发动政变未遂后被解散,随后重组为人民自由联盟党,后来与农业党合并成立了农业劳动党(PAL)。[119]PAL经过多次合并,最终成为智利人民党(Partido Nacional Popular),然后是国家行动党,最终成为民族党。

Following the fall of Nazi Germany, many Nazis fled to Chile.[120] The National Party supported the 1973 Chilean coup d’état that established the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet with many members assuming positions in Pinochet’s government. Pinochet headed a far-right dictatorship in Chile from 1973 to 1990.[121][122] According to author Peter Levenda, Pinochet was “openly pro-Nazi” and used former Gestapo members to train his own Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA) personnel.[120] Pinochet’s DINA sent political prisoners to the Chilean-German town of Colonia Dignidad, with the town’s actions being defended by the Pinochet government.[120][123][124] The Central Intelligence Agency and Simon Wiesenthal also provided evidence of Josef Mengele – the infamous Nazi concentration camp doctor known as the “Angel of Death” for his lethal experiments on human subjects – being present in Colonia Dignidad.[120][124] Former DINA member Michael Townley also stated that biological warfare weapons experiments occurred at the colony.[125]

【参考译文】纳粹德国倒台后,许多纳粹分子逃往智利。[120]民族党支持1973年智利政变,建立了奥古斯托·皮诺切特的军事独裁政权,许多成员在皮诺切特政府中担任要职。皮诺切特于1973年至1990年期间领导智利极右翼独裁政权。[121][122]据作家彼得·莱文达称,皮诺切特“公开支持纳粹”,并雇用前盖世太保成员来培训他的国家情报局(DINA)人员。[120]皮诺切特的DINA将政治犯送往智利与德国交界处的尊严殖民地镇,皮诺切特政府为该镇的行为辩护。[120][123][124]中央情报局和西蒙·维森塔尔也提供证据,表明臭名昭著的纳粹集中营医生约瑟夫·门格勒(因其对人体进行致命实验而被称为“死亡天使”)曾在尊严殖民地镇。[120][124]前DINA成员迈克尔·汤利也证实,该殖民地进行过生物战武器实验。[125]

Following the end of Pinochet’s government, the National Party would split to become the more centrist National Renewal (RN), while individuals who supported Pinochet organized Independent Democratic Union (UDI). UDI is a far-right political party that was formed by former Pinochet officials.[126][127][128][129] In 2019, the far-right Republican Party was founded by José Antonio Kast, a UDI politician who believed his former party criticized Pinochet too often.[130][131][132][133] According to Cox and Blanco, the Republican Party appeared in Chilean politics in a similar manner to Spain’s Vox party, with both parties splitting off from an existing right wing party to collect disillusioned voters.[134]

【参考译文】皮诺切特政府结束后,民族党分裂为更加中立的民族复兴党(RN),而支持皮诺切特的人则组织了独立民主联盟(UDI)。UDI是一个由前皮诺切特官员组成的极右翼政党。[126][127][128][129]2019年,由UDI政客何塞·安东尼奥·卡斯特创立的极右翼共和党成立,卡斯特认为其前党对皮诺切特的批评过于频繁。[130][131][132][133]据考克斯和布兰科称,共和党在智利政治中的出现方式与西班牙的Vox党相似,两个政党都是从现有的右翼政党中分裂出来,以争取那些感到失望的选民。[134]

5.2.4 萨尔瓦多 | El Salvador

Main article: Death squads in El Salvador【主条目:萨尔瓦多行刑队(死亡之队)】

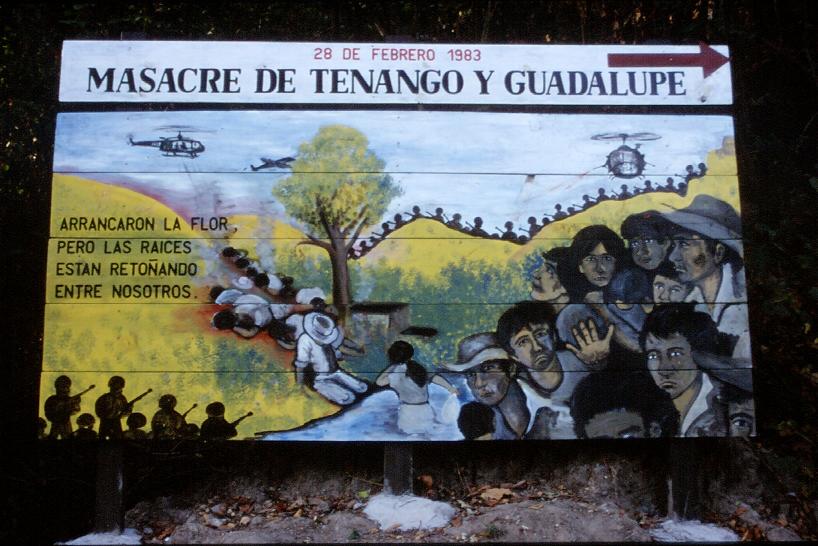

图片题注:A billboard serving as a reminder of one of many massacres in El Salvador that occurred during the civil war

参考译文:一块广告牌提醒着人们萨尔瓦多内战期间发生的众多大屠杀事件之一

图片来源:Dave Watson

During the Salvadoran Civil War, far-right death squads known in Spanish by the name of Escuadrón de la Muerte, literally “Squadron of Death, achieved notoriety when a sniper assassinated Archbishop Óscar Romero while he was saying mass in March 1980. In December 1980, three American nuns and a lay worker were gangraped and murdered by a military unit later found to have been acting on specific orders. Death squads were instrumental in killing thousands of peasants and activists. Funding for the squads came primarily from right-wing Salvadoran businessmen and landowners.[135]

【参考译文】在萨尔瓦多内战期间,一个名为“Escuadrón de la Muerte”(意为“死亡之队”)的极右翼武装部队臭名昭著,1980年3月,他们在奥斯卡·罗梅罗大主教主持弥撒时将其暗杀。1980年12月,三名美国修女和一名世俗工作人员被一支后来发现是执行特定命令的军队轮奸并杀害。死亡之队在杀害数千名农民和活动分子方面发挥了重要作用。这些部队的资金主要来自萨尔瓦多的右翼商人和地主。[135]

El Salvadorian death squads indirectly received arms, funding, training and advice during the Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations.[136] Some death squads such as Sombra Negra are still operating in El Salvador.[137]

【参考译文】在吉米·卡特、罗纳德·里根和乔治·H·W·布什执政期间,萨尔瓦多的死亡之队间接获得了武器、资金、训练和咨询。[136]一些死亡之队,如“黑色阴影”,至今仍在萨尔瓦多活动。[137]

5.2.5 洪都拉斯 | Honduras

Main article: Death squads in Honduras【主条目:洪都拉斯行刑队(死亡之队)】

Honduras also had far-right death squads active through the 1980s, the most notorious of which was Battalion 3–16. Hundreds of people, teachers, politicians and union bosses were assassinated by government-backed forces. Battalion 316 received substantial support and training from the United States through the Central Intelligence Agency.[138] At least nineteen members were School of the Americas graduates.[139][140] As of mid-2006, seven members, including Billy Joya, later played important roles in the administration of President Manuel Zelaya.[141]

【参考译文】20世纪80年代,洪都拉斯也有极右翼死亡之队活动,其中最臭名昭著的是3-16营。数百名教师、政治家和工会领袖被政府支持的部队暗杀。316营通过中央情报局获得了美国的大力支持和培训。[138]其中至少有19名成员是美洲学校毕业生。[139][140]截至2006年中,包括比利·乔亚在内的7名成员后来在总统曼努埃尔·塞拉亚的政府中发挥了重要作用。[141]

Following the 2009 Honduran constitutional crisis, former Battalion 3–16 member Nelson Willy Mejía Mejía became Director-General of Immigration[142][143] and Billy Joya was de facto President Roberto Micheletti‘s security advisor.[144] Napoleón Nassar Herrera, another former Battalion 3–16 member,[141][145] was high Commissioner of Police for the north-west region under Zelaya and under Micheletti, even becoming a Secretary of Security spokesperson “for dialogue” under Micheletti.[146][147] Zelaya claimed that Joya had reactivated the death squad, with dozens of government opponents having been murdered since the ascent of the Michiletti and Lobo governments.[144]

【参考译文】2009年洪都拉斯宪法危机后,前3-16营成员内尔森·威利·梅西亚·梅西亚成为移民总局局长[142][143],而比利·乔亚则成为总统罗伯托·米切莱蒂事实上的安全顾问。[144]另一名前3-16营成员拿破仑·纳萨尔·埃雷拉[141][145],在塞拉亚和米切莱蒂执政期间担任西北地区的警察高级专员,甚至在米切莱蒂执政期间成为安全部发言人,负责“对话”。[146][147]塞拉亚声称,乔亚重新激活了死亡之队,自米切莱蒂和洛博政府上台以来,已有数十名政府反对者被杀。[144]

5.2.6 墨西哥 | Mexico

(1)国家民族联合主义党 | National Synarchist Union

Main article: National Synarchist Union【主条目:国家民族联合主义党】

The largest far-right party in Mexico is the National Synarchist Union. It was historically a movement of the Roman Catholic extreme right, in some ways akin to clerical fascism and Falangism, strongly opposed to the left-wing and secularist policies of the Institutional Revolutionary Party and its predecessors that governed Mexico from 1929 to 2000 and 2012 to 2018.[148][149]

【参考译文】墨西哥最大的极右翼政党是国家民族联合主义党。从历史上看,它是一个罗马天主教极右翼运动,在某些方面类似于神权法西斯主义和法郎主义,强烈反对墨西哥革命制度党及其前身(从1929年至2000年以及2012年至2018年执政)的左翼和世俗政策。[148][149]

5.2.7 秘鲁 | Peru

(1)藤森主义 | Fujimorism

Further information: Fujimorism【更多信息:藤森主义】

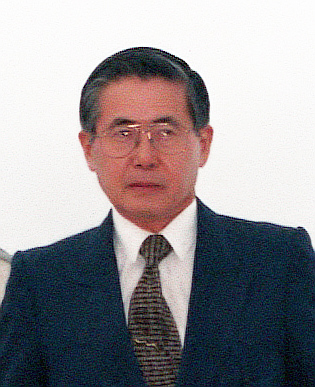

图片题注:Alberto Fujimori, the creator of Fujimorism

参考译文:藤森主义的创立者——阿尔韦托·藤森

图片来源:Staff Sergeant Karen L. Sanders, United States Air Force

During the internal conflict in Peru and a struggling presidency of Alan García, the Peruvian Armed Forces created Plan Verde, initially a coup plan that involved establishing a government that would carry out the genocide of impoverished and indigenous Peruvians, the control or censorship of media and the establishment of a neoliberal economy controlled by a military junta in Peru.[150][151][152] Military planners also decided against the coup as they expected Mario Vargas Llosa, a neoliberal candidate, to be elected in the 1990 Peruvian general election.[153][154] Vargas Llosa later reported that Anthony C. E. Quainton, the United States Ambassador to Peru, personally told him that allegedly leaked documents of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) purportedly being supportive of his opponent Alberto Fujimori were authentic, reportedly due to Fujimori’s relationship with Vladimiro Montesinos, a former National Intelligence Service (SIN) officer who was tasked with spying on the Peruvian military for the CIA.[155][156]

【参考译文】在秘鲁国内冲突和总统阿兰·加西亚执政困难时期,秘鲁武装部队制定了“绿色计划”,最初这是一个政变计划,旨在建立一个政府,对贫困和土著秘鲁人进行种族灭绝,控制或审查媒体,并在秘鲁建立一个由军政府控制的新自由主义经济。[150][151][152]军事策划者还决定不发动政变,因为他们预计新自由主义候选人马里奥·巴尔加斯·略萨将在1990年秘鲁大选中当选。[153][154]巴尔加斯·略萨后来报告说,美国驻秘鲁大使安东尼·C·E·昆顿亲自告诉他,据称中央情报局(CIA)泄露的文件支持他的对手阿尔韦托·藤森,这些文件是真实的,据说这是因为藤森与前国家情报局(SIN)官员弗拉迪米罗·蒙特西诺斯的关系,蒙特西诺斯的任务是为中央情报局监视秘鲁军队。[155][156]

An agreement was ultimately adopted between the armed forces and Fujimori after he was inaugurated president,[153] with the Fujimori implementing many of the objectives outlined in Plan Verde.[156][153] Fujimori then established Fujimorism, an ideology with authoritarian[157] and conservative traits[158][159] that is still prevalent throughout Peru’s institutions,[160] leading Peru through the 1992 Peruvian coup d’état until he fled to Japan in 2000 during the Vladivideos scandal. Following Alberto Fujimori’s arrest and trial, his daughter Keiko Fujimori assumed leadership of the Fujimorist movement and established Popular Force, a far-right political party.[161][162][163] The 2016 Peruvian general election resulted with the party holding the most power in the Congress of Peru from 2016 to 2019, marking the beginning of a political crisis. Following the 2021 Peruvian general election, far-right politician Rafael López Aliaga and his party Popular Renewal rose in popularity[164][165][166][167][168][169] and a far-right Congress – with the body’s largest far-right bloc being Popular Force, Popular Renewal and Advance Country[170] – was elected into office.[171] Following the election, La Resistencia Dios, Patria y Familia, a neofascist militant organization would promote Fujimorism and oppose President Pedro Castillo.[172][173][174]

【参考译文】藤森就任总统后,武装部队和藤森之间最终达成了一项协议,[153]藤森实施了“绿色计划”中概述的许多目标。[156][153]然后,藤森创立了藤森主义,这是一种具有权威主义[157]和保守主义特征[158][159]的意识形态,至今仍在秘鲁的各个机构中盛行,[160]藤森主义引领秘鲁度过了1992年秘鲁政变,直到藤森在2000年“录像门”丑闻期间逃往日本。在阿尔韦托·藤森被捕并接受审判后,他的女儿基科·藤森接过了藤森主义运动的领导权,并成立了极右翼政党“人民力量”。[161][162][163]2016年秘鲁大选的结果是,该党在2016年至2019年期间成为秘鲁国会中势力最大的政党,这标志着政治危机的开始。2021年秘鲁大选后,极右翼政治家拉斐尔·洛佩斯·阿里亚加和他的政党“人民复兴”人气飙升[164][165][166][167][168][169],一个极右翼国会当选,其中最大的极右翼集团包括“人民力量”、“人民复兴”和“前进国家”[170]。[171]大选后,新法西斯主义武装组织“抵抗—上帝、祖国和家庭”将宣传藤森主义,并反对总统佩德罗·卡斯蒂略。[172][173][174]

5.2.8 美国 | United States

See also: Fascism in the United States【参见:美国的法西斯主义】

In United States politics, the terms “extreme right”, “far-right”, and “ultra-right” are labels used to describe “militant forms of insurgent revolutionary right ideology and separatist ethnocentric nationalism”, according to The Public Eye.[175] The terms are used for groups and movements such as Christian Identity,[175] the Creativity Movement,[175] the Ku Klux Klan,[175] the National Socialist Movement,[175][176][177] the National Alliance,[175] the Joy of Satan Ministries,[176][177] and the Order of Nine Angles.[178] These far-right groups share conspiracist views of power which are overwhelmingly anti-Semitic and reject pluralist democracy in favour of an organic oligarchy that would unite the perceived homogeneously racial Völkish nation.[175][178] The far-right in the United States is composed of various neo-fascist, neo-Nazi, white nationalist, and white supremacist organizations and networks who have been known to refer to an “acceleration” of racial conflict through violent means such as assassinations, murders, terrorist attacks, and societal collapse, in order to achieve the building of a white ethnostate.[179]

【参考译文】据《公众之眼》报道,在美国政治中,“极端右翼”、“极右翼”和“超右翼”这些术语被用来描述“激进革命右翼意识形态和分裂的种族中心主义民族主义的军事形式”。[175]这些术语用于描述基督教身份论[175]、创造力运动[175]、三K党[175]、国家社会主义运动[175][176][177]、国家联盟[175]、撒旦喜悦事工[176][177]和九角秩序[178]等团体和运动。这些极右翼团体持有阴谋论的权力观,他们大多是反犹太主义的,拒绝多元民主,而支持有机寡头统治,以联合他们眼中同质化的种族民族国家。[175][178]美国的极右翼由各种新法西斯主义、新纳粹主义、白人至上主义和白人种族主义组织及网络组成,他们通过暗杀、谋杀、恐怖袭击和社会崩溃等暴力手段“加速”种族冲突,以建立白人种族国家,这是人所共知的。[179]

(1)激进右翼 | Radical right

Main article: Radical right (United States)【主条目:美国的激进右翼】

图片题注:Ku Klux Klan parade in Washington, D.C., September 1926

参考译文:1926 年 9 月,三 K 党在华盛顿特区的游行

图片来源:National Photo Company Collection

Starting in the 1870s and continuing through the late 19th century, numerous white supremacist paramilitary groups operated in the South, with the goal of organizing against and intimidating supporters of the Republican Party. Examples of such groups included the Red Shirts and the White League. The Second Ku Klux Klan, which was formed in 1915, combined Protestant fundamentalism and moralism with right-wing extremism. Its major support came from the urban South, the Midwest, and the Pacific Coast.[180] While the Klan initially drew upper middle class support, its bigotry and violence alienated these members and it came to be dominated by less educated and poorer members.[181]

【参考译文】从 19 世纪 70 年代开始,一直到 19 世纪末,南方出现了许多白人至上主义的准军事组织,他们的目标是组织起来对抗并恐吓共和党的支持者。这样的组织包括红衫军和白人联盟等。1915 年成立的三 K 党(第二次)将新教原教旨主义和道德主义与右翼极端主义相结合。它的主要支持者来自南方城市、中西部和太平洋沿岸。[180] 虽然三 K 党最初获得了中上阶层的支持,但其偏执和暴力行为使这些成员疏远,后来该组织主要由受教育程度较低和较贫穷的成员所主导。[181]

Between the 1920s and the 1930s, the Ku Klux Klan developed an explicitly nativist, pro-Anglo-Saxon Protestant, anti-Catholic, anti-Irish, anti-Italian, and anti-Jewish stance in relation to the growing political, economic, and social uncertainty related to the arrival of European immigrants on the American soil, predominantly composed of Irish people, Italians, and Eastern European Jews.[182] The Ku Klux Klan claimed that there was a secret Catholic army within the United States loyal to the Pope, that one million Knights of Columbus were arming themselves, and that Irish-American policemen would shoot Protestants as heretics. Their sensationalistic claims eventually developed into full-blown political conspiracy theories, to the point that the Klan claimed that Roman Catholics were planning to take Washington and put the Vatican in power and that all presidential assassinations had been carried out by Roman Catholics.[183][184]

【参考译文】20 世纪 20 年代至 30 年代,随着欧洲移民(主要是爱尔兰人、意大利人和东欧犹太人)大量涌入美国,导致美国政治、经济和社会不确定性加剧,三 K 党发展出了一种明确的本土主义、亲盎格鲁-撒克逊新教、反天主教、反爱尔兰、反意大利和反犹太的立场。[182]三 K 党声称,美国国内有一支效忠于教皇的天主教秘密军队,一百万名哥伦布骑士团成员正在武装自己,爱尔兰裔美国警察会射杀新教徒,视其为异端。他们耸人听闻的说法最终演变成了全面的政治阴谋论,以至于三 K 党声称天主教徒正计划占领华盛顿并让梵蒂冈掌权,而且所有总统遇刺事件都是天主教徒所为。[183][184]

The prominent Klan leader D. C. Stephenson believed in the antisemitic canard of Jewish control of finance, claiming that international Jewish bankers were behind the World War I and planned to destroy economic opportunities for Christians. Other Klansmen believed in the Jewish Bolshevism conspiracy theory and claimed that the Russian Revolution and communism were orchestrated by the Jews. They frequently reprinted parts of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and New York City was condemned as an evil city controlled by Jews and Roman Catholics. The objects of the Klan fear tended to vary by locale and included African Americans as well as American Roman Catholics, Jews, labour unions, liquor, Orientals, and Wobblies. They were also anti-elitist and attacked “the intellectuals”, seeing themselves as egalitarian defenders of the common man.[185] During the Great Depression, there were a large number of small nativist groups, whose ideologies and bases of support were similar to those of earlier nativist groups. However, proto-fascist movements such as Huey Long‘s Share Our Wealth and Charles Coughlin‘s National Union for Social Justice emerged which differed from other right-wing groups by attacking big business, calling for economic reforms, and rejecting nativism. Coughlin’s group later developed a racist ideology.[186]

【参考译文】著名的三 K 党领袖 D.C. 斯蒂芬森信奉反犹太主义的谣言,即犹太人控制金融,他声称第一次世界大战是由国际犹太银行家策划的,他们计划剥夺基督徒的经济机会。其他三 K 党员则相信犹太布尔什维克阴谋论,声称俄国革命和共产主义是由犹太人策划的。他们经常重印《锡安长老会纪要》的部分内容,并谴责纽约市是一座被犹太人和天主教徒控制的邪恶城市。三 K 党的恐惧对象往往因地区而异,包括非裔美国人以及美国的天主教徒、犹太人、工会、酒类、东方人和游荡无产者(Wobblies,即世界产业工人联合会成员)。他们还反对精英主义,攻击“知识分子”,将自己视为普通民众的平等主义者捍卫者。[185]在大萧条期间,出现了许多小型本土主义团体,他们的意识形态和支持基础与早期的本土主义团体相似。然而,也出现了如休伊·朗的“共享我们的财富”运动和查尔斯·库格林的“国家社会正义联盟”等准法西斯运动,它们与其他右翼团体的不同之处在于,它们攻击大企业,呼吁经济改革,并反对本土主义。库格林的团体后来发展出了种族主义意识形态。[186]

During the Cold War and the Red Scares, the far right “saw spies and communists influencing government and entertainment. Thus, despite bipartisan anticommunism in the United States, it was the right that mainly fought the great ideological battle against the communists.”[187] The John Birch Society, founded in 1958, is a prominent example of a far-right organization mainly concerned with anti-communism and the perceived threat of communism. Neo-Nazi militant Robert Jay Matthews of the White supremacist group The Order came to support the John Birch Society, especially when conservative icon Barry Goldwater from Arizona ran for the presidency on the Republican Party ticket. Far-right conservatives consider John Birch to be the first casualty of the Cold War.[188] In the 1990s, many conservatives turned against then-President George H. W. Bush, who pleasured neither the Republican Party’s more moderate and far-right wings. As a result, Bush was primared by Pat Buchanan. In the 2000s, critics of President George W. Bush‘s conservative unilateralism argued it can be traced to both Vice President Dick Cheney who embraced the policy since the early 1990s and to far-right Congressmen who won their seats during the conservative revolution of 1994.[11]

【参考译文】在冷战和红色恐慌期间,极右翼“看到间谍和共产主义者影响政府和娱乐业。因此,尽管美国两党都反对共产主义,但主要是右翼在与共产主义进行伟大的意识形态斗争”。[187]成立于 1958 年的约翰·伯奇协会是一个典型的极右翼组织,主要关注反共产主义和所谓的共产主义威胁。白人至上主义团体“秩序”的新纳粹武装分子罗伯特·杰伊·马修斯开始支持约翰·伯奇协会,尤其是当来自亚利桑那州的保守派偶像巴里·戈德华特以共和党候选人的身份竞选总统时。极右翼保守派认为约翰·伯奇是冷战的第一个牺牲品。[188]在 20 世纪 90 年代,许多保守派转而反对当时的总统乔治·H·W·布什,因为他既不能让共和党的温和派满意,也不能让极右翼满意。因此,布什在党内初选中败给了帕特·布坎南。在 21 世纪初,批评乔治·W·布什总统保守单边主义的人认为,这种单边主义可以追溯到自 20 世纪 90 年代初就支持该政策的副总统迪克·切尼,以及 1994 年保守主义革命期间当选的极右翼国会议员。[11]

Although small voluntary militias had existed in the United States throughout the latter half of the 20th century, the groups became more popular during the early 1990s, after a series of standoffs between armed citizens and federal government agents, such as the 1992 Ruby Ridge siege and 1993 Waco Siege. These groups expressed concern for what they perceived as government tyranny within the United States and generally held constitutionalist, libertarian, and right-libertarian political views, with a strong focus on the Second Amendment gun rights and tax protest. They also embraced many of the same conspiracy theories as predecessor groups on the radical right, particularly the New World Order conspiracy theory. Examples of such groups are the patriot and militia movements Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters. A minority of militia groups, such as the Aryan Nations and the Posse Comitatus, were White nationalists and saw militia and patriot movements as a form of White resistance against what they perceived to be a liberal and multiculturalist government. Militia and patriot organizations were involved in the 2014 Bundy standoff[189][190] and the 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.[191][192]

【参考译文】尽管 20 世纪后半叶,美国一直存在着小型的自愿民兵组织,但在 20 世纪 90 年代初的一系列武装公民与联邦政府特工的对峙事件之后,如 1992 年的鲁比岭围困事件和 1993 年的瓦科围困事件,这些组织变得更加流行。这些组织对他们认为的美国政府暴政表示担忧,并普遍持有宪法主义、自由主义和右翼自由主义的政治观点,强烈关注第二修正案规定的枪支权利和税收抗议。他们还接受了极端右翼前辈组织的许多相同的阴谋论,特别是新世界秩序的阴谋论。这类组织的例子包括爱国者运动和民兵组织“誓言守护者”和“百分之三者”。少数民兵组织,如雅利安民族和波西·科米塔图斯,是白人民族主义者,他们认为民兵和爱国者运动是对他们所认为的自由和多文化主义政府的一种白人抵抗形式。民兵和爱国者组织参与了 2014 年的邦迪对峙事件[189][190]和 2016 年马卢尔国家野生动物保护区占领事件[191][192]。

图片题注:National Socialist Movement rally on the west lawn of the US Capitol, Washington, DC, 2008

参考译文:2008 年美国华盛顿特区国会大厦西草坪上的国家社会主义运动集会

图片来源:Utilisateur bootbeardbc de flickr

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the counter-jihad movement, supported by groups such as Stop Islamization of America and individuals such as Frank Gaffney and Pamela Geller, began to gain traction among the American right. The counter-jihad members were widely dubbed “Islamophobic” for their vocal criticism of the Islamic religion and its founder Muhammad,[193] and their belief that there was a significant threat posed by Muslims living in America.[193] Its proponents believed that the United States was under threat from “Islamic supremacism”, accusing the Council on American-Islamic Relations and even prominent conservatives such as Suhail A. Khan and Grover Norquist of supporting radical Islamist groups and organizations, such as the Muslim Brotherhood. The alt-right emerged during the 2016 United States presidential election cycle in support of the Donald Trump‘s presidential campaign (see: Trumpism). It draws influence from paleoconservatism, paleolibertarianism, white nationalism, the manosphere, and the Identitarian and neoreactionary movements. The alt-right differs from previous radical right movements due to its heavy internet presence on websites such as 4chan.[194]

【参考译文】2001 年 9 月 11 日袭击事件之后,在美国阻止伊斯兰化组织(Stop Islamization of America)以及弗兰克·加夫尼(Frank Gaffney)和帕梅拉·盖勒(Pamela Geller)等人的支持下,反圣战运动开始在美国右翼中逐渐获得支持。反圣战成员因其公开批判伊斯兰教及其创始人穆罕默德,[193]并认为居住在美国的穆斯林构成了重大威胁,[193]而被广泛称为“伊斯兰恐惧症者”。该运动的支持者认为美国正面临“伊斯兰至上主义”的威胁,指责美国伊斯兰关系理事会,甚至指责苏海尔·A·可汗(Suhail A. Khan)和格罗弗·诺奎斯特(Grover Norquist)等著名保守派人士支持穆斯林兄弟会等激进伊斯兰组织。另类右翼(alt-right)在 2016 年美国总统大选期间出现,以支持唐纳德·特朗普(Donald Trump)的总统竞选活动(见:特朗普主义)。它受到古保守主义、古自由意志主义、白人民族主义、男性领域以及身份认同主义和新反动主义运动的影响。另类右翼与之前的极端右翼运动不同,因为它在 4chan 等网站上的网络影响力很大。[194]

Chetan Bhatt, in White Extinction: Metaphysical Elements of Contemporary Western Fascism, says that “The ‘fear of white extinction’, and related ideas of population eugenics, have travelled far and represent a wider political anxiety about ‘white displacement’ in the US, UK, and Europe that has fuelled the right-wing phenomena referred to by that sanitizing word ‘populism‘, a term that neatly evades attention to the racism and white majoritarianism that energizes it.”[195]

【参考译文】切坦·巴特(Chetan Bhatt)在《白人灭绝:当代西方法西斯主义的形而上学元素》一书中说,“‘对白人灭绝的恐惧’以及与之相关的人口优生学观念流传甚广,代表了美国、英国和欧洲对‘白人被取代’的更广泛的政治焦虑,这种焦虑助长了用‘民粹主义’这一粉饰之词所指称的右翼现象,该词巧妙地避开了对其背后的种族主义和白人至上主义的关注,而正是这些因素为其注入了活力。”[195]

5.2.9 其他国家和地区

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

5.3 亚洲 | Asia

See also: Fascism in Asia【参见:亚洲的法西斯主义】

5.3.1 中国 | China

In the 21st century, far-right Chinese nationalism has been criticized for being used to justify oppression of the Xinjiang, Hong Kong region and a lack of human rights improvement,[196][197] but full-scale ultranationalism is deemed to be unlikely.[198] The Chinese Communist Party and its general secretary Xi Jinping have also tolerated or moved closer toward ultraconservative[199] and Han-centric values.[200][201]

【参考译文】21 世纪,极右翼中国民族主义被批评为压迫新疆、香港地区和人权状况欠佳的借口,[196][197] 但全面极端民族主义不太可能出现。[198] 中国共产党及其总书记习近平也容忍或更接近极端保守主义[199] 和汉族中心主义价值观。[200][201]

Jiang Shigong is considered a major promoter of the ideas of Carl Schmitt and neoauthoritarianism in China.[202] Some intellectuals “flirted” with neoconservatism and its “fascistic-like characteristics”, but they have not gained wide appeal.[203]

{参考译文】强世功被认为是卡尔·施密特思想和中国新威权主义的主要推动者。[202] 一些知识分子“调情”新保守主义及其“法西斯主义特征”,但他们并没有获得广泛的吸引力。[203]

5.3.2 印度 | India

Bharatiya Janata Party in India has been claimed to combine economic nationalism with religious nationalism.[204]

【参考译文】印度人民党据称将经济民族主义与宗教民族主义相结合。[204]

5.3.3 印度尼西亚 | Indonesia

Some islamists in Indonesia are far-right.[205]

【参考译文】印度尼西亚的一些伊斯兰主义者是极右翼人士。[205]

5.3.4 以色列 | Israel

Main articles: Far-right politics in Israel and Kach (political party)

【主条目:以色列的极右翼政治和卡奇(政党)】

图片题注:Flag of Kach, used by Kahanists

参考译文:卡哈尼派使用的卡奇旗帜

图片来源:R-41

Kach was a radical Orthodox Jewish, religious Zionist political party in Israel, existing from 1971 to 1994.[206] Founded by Rabbi Meir Kahane in 1971, based on his Jewish-Orthodox-nationalist ideology subsequently known as Kahanism, which held the view that most Arabs living in Israel are enemies of Jews and Israel itself, and believed that a Jewish theocratic state, where non-Jews have no voting rights, should be created.[207] The party secured a single seat in the Knesset in the 1984 election,[208] but was subsequently barred from standing in elections, and both it and Kahanism organisations were banned outright in 1994 by the Israeli cabinet under 1948 anti-terrorism laws,[209] following statements by it in support of the 1994 Cave of the Patriarchs massacre by a Kach supporter.[210]

【参考译文】卡赫党是以色列的一个激进的正统犹太宗教复国主义政党,存在时间从 1971 年到 1994 年。[206] 该党由拉比梅尔·卡哈纳于 1971 年创立,基于他的犹太正统民族主义意识形态,后来被称为卡哈主义,该意识形态认为,大多数居住在以色列的阿拉伯人都是犹太人和以色列本身的敌人,并认为应该建立一个非犹太人没有投票权的犹太神权国家。[207] 该党在 1984 年的选举中获得了议会的一个席位,[208] 但随后被禁止参加选举,1994 年,以色列内阁根据 1948 年的反恐法彻底禁止了该党和卡哈主义组织,[209] 此前该党发表声明支持 1994 年卡赫支持者在族长洞穴进行的屠杀。[210]

In 2015, the Kach party and Kahanist movement were believed to have an overlapping membership of fewer than 100 people,[211][212] with links to the modern party Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power) party,[213][214] which, running on a Kahanist and anti-Arab platform,[215][216] won six seats in the 2022 Israeli legislative election, having run jointly with fellow far-right parties Religious Zionist Party and Noam.[217][218] The thirty-seventh government of Israel which formed after the 2022 Israeli legislative election as subsequently been critiqued as Israel’s most hardline and far-right government to date.[219][220] The coalition government consists of six parties: Likud, United Torah Judaism, Shas, Otzma Yehudit, Religious Zionist Party and Noam, so having half of its coalition partners hailing from the far-right. The government has been noted for its significant shift towards far-right policies, and the appointment of controversial far-right politicians, including Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, to positions of considerable influence.[221]

【参考译文】2015 年,卡赫党和卡哈尼主义运动据信重叠成员人数不足 100 人[211][212],与现代政党犹太力量党(Otzma Yehudit)[213][214]有联系,该党以卡哈尼主义和反阿拉伯平台运行[215][216],在 2022 年以色列立法选举中赢得了六个席位,与其他极右翼政党宗教犹太复国主义党和诺姆党联合参选。[217][218] 2022 年以色列立法选举后组建的以色列第 37 届政府随后被批评为以色列迄今为止最强硬和最极右翼的政府。[219][220]联合政府由六个政党组成:利库德集团、联合托拉犹太教、沙斯党、奥兹玛耶胡迪特、宗教犹太复国主义党和诺姆党,因此其半数联盟伙伴来自极右翼。该政府因其向极右翼政策的重大转变以及任命有争议的极右翼政客(包括伊塔马尔·本-格维尔和贝扎莱尔·斯莫特里奇)担任有相当影响力的职位而闻名。[221]

5.3.5 日本 | Japan

Main articles: Ultranationalism (Japan) and Uyoku dantai【主条目:极端民族主义(日本)和右翼团体】

Further information: Racism in Japan【更多信息:日本的种族主义】

图片题注:日本极右翼团体在锦糸町车站南口广场进行演说

图片来源:User:Ellery

In 1996, the National Police Agency estimated that there were over 1,000 extremist right-wing groups in Japan, with about 100,000 members in total. These groups are known in Japanese as Uyoku dantai. While there are political differences among the groups, they generally carry a philosophy of anti-leftism, hostility towards China, North Korea and South Korea, and justification of Japan’s role and war crimes in World War II. Uyoku dantai groups are well known for their highly visible propaganda vehicles fitted with loudspeakers and prominently marked with the name of the group and propaganda slogans. The vehicles play patriotic or wartime-era Japanese songs. Activists affiliated with such groups have used Molotov cocktails and time bombs to intimidate moderate Japanese politicians and public figures, including former Deputy Foreign Minister Hitoshi Tanaka and Fuji Xerox Chairman Yotaro Kobayashi. An ex-member of a right-wing group set fire to Liberal Democratic Party politician Koichi Kato‘s house. Koichi Kato and Yotaro Kobayashi had spoken out against Koizumi’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine.[222] Openly revisionist, Nippon Kaigi is considered “the biggest right-wing organization in Japan.”[223][224]

【参考译文】1996 年,日本国家警察厅估计日本有 1,000 多个极右翼团体,总成员约 100,000 人。这些团体在日语中被称为“右翼团体”。虽然这些团体之间存在政治分歧,但他们通常都秉持反左翼主义的理念,敌视中国、朝鲜和韩国,并为日本在二战中的作用和战争罪行辩护。右翼团体以其显眼的宣传车辆而闻名,这些车辆配备扩音器,并在显著位置标有团体名称和宣传口号。车辆播放爱国歌曲或战时日本歌曲。与此类团体有关的活动人士使用燃烧瓶和定时炸弹来恐吓日本温和派政治家和公众人物,包括前外务省副相田中均和富士施乐董事长小林洋太郎。一名前右翼组织成员纵火焚烧了自民党政客加藤光一的住宅。加藤光一和小林阳太郎曾公开反对小泉参拜靖国神社。[222] 日本会议公开宣称修正主义,被认为是“日本最大的右翼组织”。[223][224]

5.3.4 马来西亚 | Malaysia