中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。

辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及根据名称精确检索已搬运的词条,请点击这里访问辽观网站。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

图片题注:Du Wenxiu’s headquarters in Dali, Yunnan; now the Dali City Museum

参考译文:杜文秀在云南大理的总部;现为大理市博物馆

图片来源:Brücke-Osteuropa

Du Wenxiu (Chinese: 杜文秀; pinyin: Dù Wénxiù; Wade–Giles: Tu Wen-hsiu, Xiao’erjing: ٔدُﻮْ وٌ ﺷِﯿَﻮْ ْ; 1823 – 1872) was the Chinese Muslim leader of the Panthay Rebellion, an anti-Qing revolt in China during the Qing dynasty. Du Wenxiu was ethnically Han from both his parents and not Hui but was raised as a Muslim and led his rebellion as an anti-Manchu rebellion instead of a religious war by Muslims against non-Muslims.[1][2][3][4]

【参考译文】杜文秀(中文:杜文秀;拼音:Dù Wénxiù;威妥玛译本:杜文秀;1823年 – 1872 年)是清朝时期中国反清起义“班赛起义”的中国穆斯林领袖。杜文秀的父母都是汉族,不是回族,但他在穆斯林家庭长大,并将他的起义视为反满族起义,而不是穆斯林针对非穆斯林的宗教战争。[1][2][3][4]

杜文秀(1827年—1872年),本名杨秀,字云焕,号百香,回族,大清云南省永昌府保山县人,清朝云南回变首领,领导了清末的云南回族穆斯林起义。[1][2]

目录

1. 生平

1.1 早年生活和背景 | Early life and background

杜文秀,本名杨秀,清道光七年(1827年)[3][2][另说1823年。[1][4]]生于永昌府治保山县金鸡村(今保山市隆阳区金鸡乡金鸡村)[另说保山县板桥杜家庄。[4]]的一个回族商人家庭[5],生活条件优越,十岁时承嗣舅家,从舅姓,取名文秀[1]。杜文秀自幼好学,通晓伊斯兰经典,14岁考取秀才,16岁补廪生[2]。

1855年,又发生汉族矿工与回族矿工的冲突,云南巡抚密令各地“聚团杀回”,云南各地的回民蜂涌反抗。杜文秀以清政府官吏贪污滥杀为由,于云南蒙化(今巍山)一地号召回民反抗清朝政权,提出“兴汉”“锄满”“除奸”也联合当地汉族及其他民族的民众参与该反清斗争。起事后,他攻陷大理府等云南50座城市,几乎占据云南全省,与占据昆明的马如龙遥遥相对;不久,建立政权,自任总统兵马大元帅,任命蔡发春为大都督、马金保为大将军、李国纶为大司空。他主张“三教同心,联为一体”,“三教”是佛教、伊斯兰教与彝族宗教[7]。

He became respected among Yunnanese Hui when he and two others travelled to Beijing and petitioned the imperial court for compensation for the 1845 Baoshan Massacre of the Hui. After he failed to secure a settlement from the Qing administration, Du traveled through western Yunnan’s trading networks on behalf of his family. The experience of his travels made him conscious of the commercial, political, and multiethnic landscape of Yunnan.[6]

【参考译文】他和另外两人前往北京,向朝廷请愿,要求对 1845 年保山回民惨案作出赔偿,从此在云南回民中赢得了尊敬。在未能从清政府获得赔偿后,杜文秀代表家人游历了云南西部的贸易网络。旅行经历使他意识到云南的商业、政治和多民族格局。[6]

The rebellion started after massacres of Hui perpetrated by the Qing authorities.[7] Du used anti-Manchu rhetoric in his rebellion against the Qing, calling for Han to join the Hui to overthrow the Manchu-led Qing dynasty after 200 years of their rule.[8][9]

【参考译文】这场叛乱是在清政府屠杀回民后爆发的。[7]杜文秀在反清叛乱中使用反满言论,呼吁汉人加入回民,推翻满族统治了 200 多年的清朝。[8][9]

Du invited the fellow Hui Muslim leader Ma Rulong to join him in driving the Manchus out and “recover China”.[10] For his war against Manchu “oppression”, Du “became a Muslim hero”, while Ma Rulong defected to the Qing.[11] On multiple occasions Kunming was attacked and sacked by Du Wenxiu’s forces.[12][13] He was the father of Du Fengyang, who also participated in the rebellion.

【参考译文】杜文秀邀请回民领袖马如龙与他一起驱逐满族人并“恢复中国”。[10] 杜文秀反抗满族“压迫”,成为“穆斯林英雄”,而马如龙则投奔清朝。[11] 昆明多次遭到杜文秀军队的攻击和洗劫。[12][13] 杜文秀是杜凤阳的父亲,杜凤阳也参与了叛乱。

Ma Shilin, a descendant of Ma Mingxin joined the Panthay rebels as a garrison commander and civil official, meeting his end at the fortress of Donggouzhai after a year-long Qing siege.[14]

【参考译文】马明信的后代马士林加入了潘塞叛军,担任驻军指挥官和文官,在清军围困东沟寨一年后,在东沟寨堡垒中丧生。[14]

1855年,又发生汉族矿工与回族矿工的冲突,云南巡抚密令各地“聚团杀回”,云南各地的回民蜂涌反抗。杜文秀以清政府官吏贪污滥杀为由,于云南蒙化(今巍山)一地号召回民反抗清朝政权,提出“兴汉”“锄满”“除奸”也联合当地汉族及其他民族的民众参与该反清斗争。起事后,他攻陷大理府等云南50座城市,几乎占据云南全省,与占据昆明的马如龙遥遥相对;不久,建立政权,自任总统兵马大元帅,任命蔡发春为大都督、马金保为大将军、李国纶为大司空。他主张“三教同心,联为一体”,“三教”是佛教、伊斯兰教与彝族宗教[7]。

1.2 与马如龙的关系 | Relationship with Ma Rulong

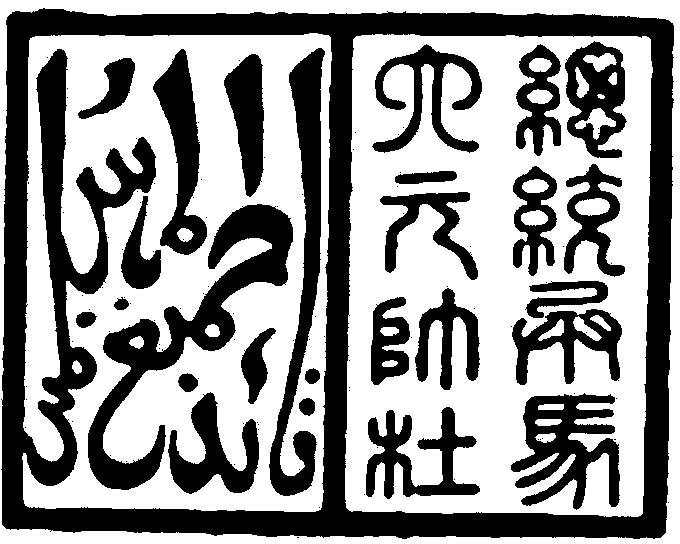

图片题注:杜文秀所用印,左侧为阿拉伯语“Qa’id jami al-muslimin”,意为“穆民的指挥官卡迪”,右侧为汉文篆字“总统兵马大元帅杜”

图片来源:Emile Rocher

In Kunming, there was a slaughter of 3,000 Muslims on the instigation of the judicial commissioner, who was a Manchu, in 1856. Du Wenxiu was of Han Chinese origin despite being a Muslim and he led both Hui Muslims and Han Chinese in his civil and military bureaucracy. Du Wenxiu was fought against by another Hui leader who defected to the Qing dynasty, Ma Rulong.[15] Ma claimed that the central government was not responsible for the massacres of the Yunnanese Hui & that the blame lay with corrupt local officials. He tried to convince Du Wenxiu to lay down his arms and make peace as all Muslims were one family. Du responded to Ma’s letter In less than a week; categorically refuting his claims & pointed out that Ma’s defection was the reason Muslims had become divided.[16] In a memorial, Du asked Ma Dexin to intervene so that Ma Rulong would end the criminal act “of killing his fellow Muslims (tongjiao)”[17]

【参考译文】1856 年,在昆明,满族司法专员煽动屠杀了 3,000 名穆斯林。杜文秀虽然是穆斯林,但其实是汉族人,他在文武官僚机构中领导回族穆斯林和汉族人。杜文秀遭到另一位叛逃清朝的回族领袖马如龙的反对。[15] 马声称,中央政府对云南回民的屠杀不负责任,责任在于腐败的地方官员。他试图说服杜文秀放下武器,讲和,因为所有穆斯林都是一家人。杜文秀在不到一周的时间内回复了马的信;断然驳斥了他的主张,并指出马的叛逃是穆斯林分裂的原因。[16]杜在奏折中请求马德新介入,让马如龙停止“杀害同胞”的犯罪行为[17]

1.3 与马德信的关系 | Relationship with Ma Dexin

Ma Dexin was the most prominent Hui scholar in Yunnan. He used his prestige to act as a mediator between the different Hui factions & “helped orient and validate” the rebellion throughout the province.[18] He was respected by both Du Wenxiu & Ma Rulong as a spiritual leader.[19] In 1860; Ma Dexin sent forces to help Du Wenxiu fight the Qing; assuring him that:

【参考译文】马德信是云南最杰出的回族学者。他利用自己的威望充当不同回族派别之间的调解人,并“帮助引导和确认”全省的叛乱。[18] 杜文秀和马如龙都尊他为精神领袖。[19] 1860 年,马德信派部队帮助杜文秀对抗清朝;他向他保证:

“I have already secretly ordered my disciples [mensheng] Ma [Rulong] as the Grand Commander of Three Directions, with Ma Rong as second in command . . . to launch a rearguard attack from their base in Yimen.”[20]

【参考译文】“我已秘密命令我的弟子 [门生] 马 [如龙] 为三方总兵,马荣为副指挥官……从他们在义门的基地发动后卫攻击。”[20]

There is evidence that Ma Dexin, Ma Rulong & the Hui forces with them only pretended to surrender (in 1862) in order to gain access to the city of Kunming. Even after their supposed capitulation to the Qing; Ma Rulong continued to issue proclamations using his seal “Generalissimo of the Three Directions” while Ma Dexin refused to accept the Civil title granted to him; not wanting to be associated with the Qing regime. The Hui rebels taunted the Hui who hadn’t joined the rebellion as being fake Hui (jia Huizi). Taiwanese researcher Li Shoukong asserts that in responding to the Qing offer for surrender; Ma Rulong acted hastily with no plan or thought other than to gain access to the Walled city of Kunming. Many Hui rebels had employed a similar tactic in the early years of the rebellion.[21]

【参考译文】有证据表明,马德信、马如龙和他们的回族部队只是为了进入昆明市而假装投降(1862 年)。即使在他们向清朝投降之后;马如龙继续用他的印章“三方大元帅”发布公告,而马德信拒绝接受授予他的文官头衔,不想与清朝政权扯上关系。回民叛军嘲笑没有参加叛乱的回民是假回民(假回民)。台湾研究者李守空断言,在回应清朝的投降提议时,马如龙行动仓促,除了进入昆明城墙外,没有其他计划或想法。许多回民叛军在叛乱初期都采用了类似的策略。[21]

1862年,颁刊大元帅杜新镌的《宝命真经》阿拉伯文版30卷,为中国最早的《古兰经》木刻本。

To test his loyalty Ma Rulong was sent to pacify the disgruntled magistrate of Lin’an (in Southern Yunnan). A few weeks after Ma Rulong left the city; rebel forces led by Ma Rong and Ma Liansheng stormed Kunming & captured it. Ma Rulong’s forces had come to believe that he could no longer be trusted to achieve their goal of uniting under a single rebel government. Seeking to join Du Wenxiu and unite in opposition to the Qing; the Hui raised the white banner of the Pingnan State, dropped regional references and began to refer to themselves from this point on as Muslims. In 1863 Ma Dexin declared himself “King-Who-Pacifies-the-South (Pingnan Wang)”, seized the official seals & stopped using the Qing reign year when dating documents. Ma Dexin hoped to keep the rebel forces united under him until he could hand over control to Du Wenxiu.[22]

【参考译文】为了测试他的忠诚度,马如龙被派去安抚临安(云南南部)心怀不满的县令。马如龙离开这座城市几周后,由马荣和马连胜领导的叛军袭击了昆明并占领了这座城市。马如龙的势力开始相信,他不再能实现统一叛军政府的目标。回民们寻求与杜文秀联手,联合起来反对清朝,于是举起了平南国的白旗,放弃了地方称谓,从此开始称自己为穆斯林。1863 年,马德信自封为“平南王”,夺取了官印,不再使用清朝的年号来书写文件。马德信希望叛军能够团结在他身边,直到他能把控制权移交给杜文秀。[22]

Ma Rulong immediately rushed back to Kunming, He was rebuked by his followers who told him that “If you only crave to be an official with no thought for your fellow Muslims, you should return to [your home in] Guanyi.” Ma Rulong attacked the city along with Qing forces; ordered Ma Dexin to give up his seals of office & placed him under house arrest.[23] Ma Dexin also opposed Ma Rulong’s acceptance of the Qing policy of “using Hui to fight other Hui”.[24]

【参考译文】马如龙立即赶回昆明,他的追随者斥责他说:“如果你只渴望当官,不考虑穆斯林同胞,你应该回到关义。”马如龙与清军一起攻城;命令马德信交出印章,并将他软禁。[23] 马德信还反对马如龙接受清朝“以回攻回”的政策。[24]

Ma Dexin was sent to convince Du Wenxiu to surrender in 1864. He was sympathetic to Du’s cause but saw no point in continuing to resist anymore. He told Du that the Hui must not fall into the trap of the Qing & that with the end of the Taipeng rebellion the Qing would bring their full force to bear to crush the Hui. Du refused to surrender instead he offered Ma Dexin a position in his government.[25]

【参考译文】1864 年,马德信被派去劝说杜文秀投降。他同情杜文秀的事业,但认为继续抵抗已经没有意义了。他告诉杜文秀,回民绝不能落入清朝的陷阱,随着太鹏叛乱的结束,清朝将全力镇压回民。杜文秀拒绝投降,反而给马德信提供了一个政府职位。[25]

1.4 失败与遗产 | Defeat and legacy

1867年,马如龙投降清朝的云南代理布政使岑毓英。杜文秀率部御驾亲征在昆明包围战失败,由于经验不足,指挥不当,围城一年多也未攻下昆明,形势恶化。杜退守大理,自此情势逆转。

During his last offensive in 1867; Du Wenxiu declared in his “Proclamation from the Headquarters of the Generalissimo”, that:

【参考译文】1867 年,杜文秀在最后一次进攻中,在《大元帅府诰》中宣称:

“this army expedition was caused by the Manchus’ taking China from us and staying in power for more than two hundred years, treating people as oxen and horses, having no regard for the value of life, hurting my compatriots, and wiping out my fellow Hui (wo Huizu).”[39]

【参考译文】“此次大军出征,乃因满族夺取中国,执掌政权二百余年,视人民为牛马,不顾生命价值,残害同胞,灭绝回族同胞。”[39]

He styled himself “Sultan of Dali” and reigned for 16 years before Qing troops under Cen Yuying beheaded him after he swallowed a ball of opium.[40][41][42][43][44] The Qing eventually battled their way to Dali and on December 25,1872; thousands of Qing troops encircled Dali. Du’s top general Yang Rong advised him to surrender fearing disastrous consequences for the populace if resistance continued. Du concurred and decided to surrender the next morning, telling his council that: [45]

【参考译文】他自封为“大理苏丹”,在位 16 年,直到岑毓英率领清军在他吞下鸦片丸后斩首。[40][41][42][43][44]清军最终一路攻入大理,1872 年 12 月 25 日,数千名清军包围了大理。杜文秀的上将杨荣劝他投降,担心如果继续抵抗,人民将遭受灾难性的后果。杜同意了,并决定第二天早上投降,告诉他的参谋们:[45]

“What you have said is true. If this generalissimo [Du] decides to fight to the death, then truly not even a chicken or dog will be left alive. If this generalissimo leaves the city, then I can save the old and the young.”

【参考译文】“你说的没错。如果杜大将军决定战斗至死,那么真的鸡狗都活不下来。如果杜大将军离开这座城市,那么我可以拯救老幼。”

1869年,清军反攻,起义军失利,退回滇西。

1872年,太平天国失败后,清军集中优势兵力直至大理,被清军攻陷,11月26日,杜文秀弹尽粮绝,为免遭屠城,杜文秀服毒药孔雀胆后着礼服自杀,被抬送至清军大本营。

He had handed himself over to the Qing hoping that the city’s residents would be spared, telling General Yang Yuke “spare the people (shao sharen)”.[45] However the Qing troops carried out a bloody massacre of the Hui populace; killing ten thousand people (four thousand of whom were women, children and the elderly). Du’s head was encased in honey & sent to Beijing along with 24 baskets filled with the ears of the dead.[46] Du’s body is entombed in Xiadui.[47]

【参考译文】他投降清朝,希望这座城市的居民能幸免于难,并告诉杨玉克将军“放过人民”。[45]然而,清军对回民进行了血腥大屠杀;杀死了一万人(其中四千人是妇女、儿童和老人)。杜的头被包在蜂蜜里,连同24个装满死者耳朵的篮子一起送到了北京。[46]杜的遗体被埋葬在下堆。[47]

His capital was Dali.[48] The revolt ended in 1873.[49] Du Wenxiu is regarded as a hero by the present day government of China.[50]

【参考译文】他的首都是大理。[48]起义于1873年结束。[49]杜文秀被当今中国政府视为英雄。[50]

1874年,清军完全镇压这次叛乱。

Du Wenxiu’s life and related historical facts are a major element of Tariq Ali‘s novel Night of the Golden Butterfly.[citation needed]

【参考译文】杜文秀的生平和相关史实是塔里克·阿里小说《金蝴蝶之夜》的主要内容。[引文需要]

2. 杜文秀大理苏丹国的政策 | Policies of Du Wenxiu’s Dali sultanate

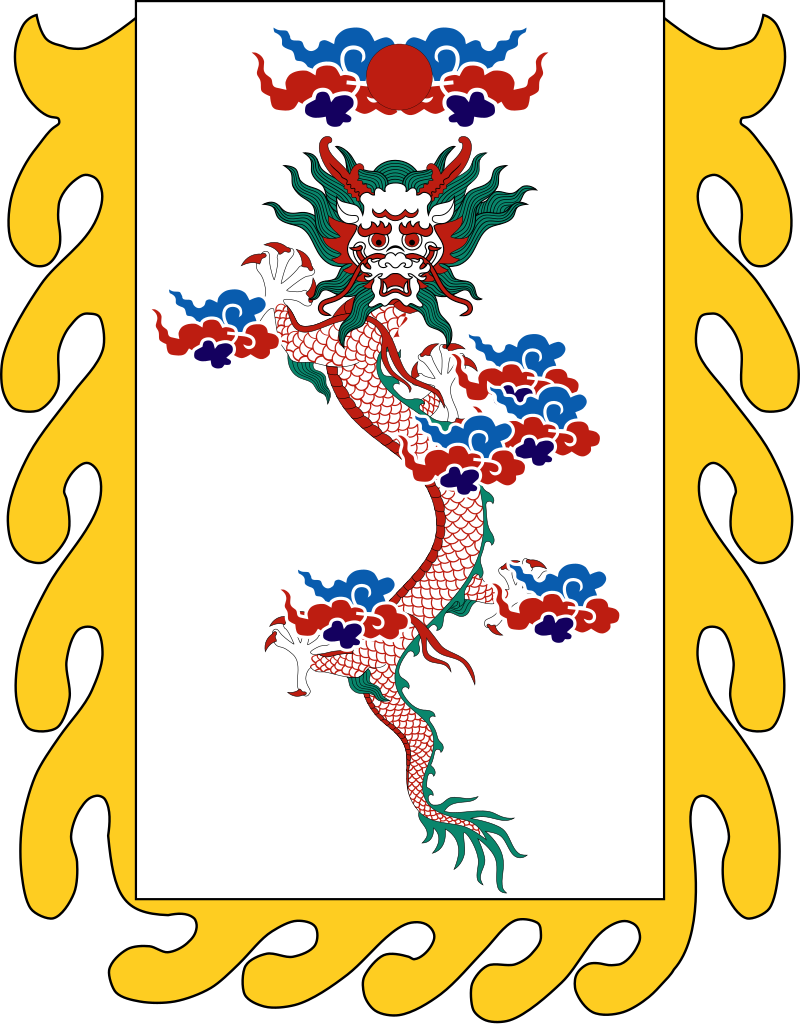

图片题注:杜文秀使用的旗帜

图片来源:Unknown. File originally by Samhanin

After Du Wenxiu became leader of the new state based in Dali; he ordered the repairing of the city’s main mosque & the construction of 5 new mosques. To revitalize Islamic education in Yunnan Du Wenxiu established Islamic Madrassas, promoted the use of the Arabic language among the Hui & printed the first copy of the Quran in China.[26]

【参考译文】杜文秀成为大理新国家的领导人后,下令修复城市的主要清真寺并建造 5 座新清真寺。为了振兴云南的伊斯兰教育,杜文秀建立了伊斯兰教学校,在回民中推广使用阿拉伯语,并在中国印刷了第一份《古兰经》。[26]

The Sultanate’s bureaucracy employed Arabic as the preferred language for communication among the Hui elite and the preferred language for foreign diplomatic relations. When the first British envoys arrived in Yunnan from Burma they were presented with documents entirely in Arabic and had to wait several days for it to be translated into Chinese.[27]

【参考译文】苏丹国的官僚机构使用阿拉伯语作为回民精英交流的首选语言,也是外交关系的首选语言。当第一批英国使节从缅甸抵达云南时,他们收到的文件全部用阿拉伯语书写,不得不等待数天才能将其翻译成中文。[27]

Instead of wearing queues as mandated by the Qing the male subjects of Sultanate let their hair grow long. And the Qing referred to the rebels as “long-haired rebels (changfa Huijei)”. The Dali regime used White Banners.[28]

【参考译文】苏丹国的男性臣民没有按照清朝的规定留辫子,而是留着长发。清朝称叛乱者为“长发叛徒(长发回民)”。大理政权使用白旗。[28]

A state proclamation sent to the Muslims of Lhasa in the early 1860s (by way of Hui caravan traders) justified the rebellion as a righteous response to treachery by idolaters. The declaration was written in Arabic and was filled with Qur’anic and Islamic metaphors. It described the Pingnan rebellion using Islamic terminology:

【参考译文】19 世纪 60 年代初,一份由回族商队商人发给拉萨穆斯林的政府公告为这次叛乱辩护,称这是对偶像崇拜者背叛行为的正义回应。这份公告以阿拉伯语书写,充满了《古兰经》和伊斯兰教的隐喻。它用伊斯兰教术语描述了平南叛乱:

“The cause of the dispute was that the Idolaters and their chiefs assembled together to kill the Muslims and began to insult their religion…. Having abandoned every hope of life, we fought with the Idolaters and God gave us the victory…. [The ruler’s] name is Sadik, otherwise called Suleiman. He has now established Islamic Law. He administers justice according to the dictates of the Qur’an and their traditions. Since we have made him our Imam we have been by the decree of God, very victorious…. The Ministers and chiefs under our Imam are as single-hearted as Abu Bakr and as bold as Ali. No one can face them in battle. They are imperious to the Infidel but meek to the Muslim. The metropolis of Infidelity has become a city of Islam!”[29]

【参考译文】“争端的起因是偶像崇拜者和他们的首领们聚在一起杀害穆斯林,并开始侮辱他们的宗教……我们放弃了一切生存的希望,与偶像崇拜者战斗,真主赐予我们胜利……[统治者]的名字是萨迪克,也叫苏莱曼。他现在已经制定了伊斯兰教法。他根据《古兰经》和他们的传统来执行正义。自从我们把他任命为我们的伊玛目以来,我们按照真主的旨意取得了巨大的胜利……我们伊玛目手下的部长和首领们和阿布·巴克尔一样一心一意,和阿里一样勇敢。没有人能在战斗中与他们对抗。他们对异教徒很傲慢,但对穆斯林却很温顺。异教徒的大都市已经成为伊斯兰之城!”[29]

The Dali Sultanate used Imperial Chinese Symbols & challenged the Qing by using Ming era Imagery.[29] Du tried to highlight the foreign nature of Manchu rule even in dress; and his own imperial robes were from the “Chinese” Ming dynasty.[30] According to David G. Atwill: “The regime reflected the strong interethnic ties of the Hui with the Han and of the Yi with predominantly Han-Islamic imagery and a heavily indigenized presence in its institutions and rule.”[31] Du Wenxiu cited the example of the Nanzhao Kingdom, as proof for the feasibility of an Independent Yunnan based government:

【参考译文】大理苏丹国使用中国帝国的象征,并借用明朝的图像向清朝发起挑战。[29] 杜文秀甚至在服饰上也试图凸显满族统治的外来性质;他自己的皇帝长袍来自“中国”明朝。[30] 戴维·G·阿特威尔认为:“该政权反映了回族与汉族以及彝族之间的强烈民族联系,以汉族-伊斯兰图像为主,其制度和统治具有浓厚的本土化色彩。”[31] 杜文秀引用了南诏国的例子,作为在云南建立独立政府的可行性的证明:

“if we cannot realize far-reaching permanent victory, we can still achieve a smaller, more remote success like that of the Nanzhao Kingdom, which lasted eight hundred years”.[32]

【参考译文】“如果我们不能取得深远的、永久的胜利,那么我们仍然可以取得像南诏国那样持续了八百年的较小、较遥远的成功”。[32]

The power of the Hui State between the years 1863-68 was described by the French missionary Father Ponsot: [33]

【参考译文】法国传教士彭索神父曾这样描述 1863 年至 1868 年间回族政权的实力:[33]

“Since the Hui occupied Dali they have become consistently stronger and more or less the masters of the land. They control almost all the towns around Zhongdian, Heqing and Lijiang extending almost up to Tibet, land of the lamas.”

【参考译文】“自从回族占领大理以来,他们势力不断壮大,几乎成了这片土地的主人。他们控制了中甸、鹤庆和丽江周边几乎所有城镇,几乎延伸到喇嘛的土地西藏。”

Areas under rule of the Dali Sultanate were widely considered to be far safer and less corrupt than the areas under imperial control. European travelers observed that a “calm tranquility reigned over this country”.[34] Traders “lauded the security of the White banner [Dali-controlled] territory” and locals attributed the presence of prosperous trade to Du Wenxiu’s efforts to “trade as much as possible, both by the imposition of light duties and a rigorous administration of justice.” The Dali government created policies to encourage locals to protect trade caravans and ordered officials to guard the main passes into Yunnan and to provide free lodging to traders. Du Wenxiu himself set up a trading company in Burma and also established two cotton trading bureaus in Ava, one of them operated by his sister.[35][36] Religious instructions called upon Yunnanese Muslims and traders to not contradict Islamic Law: [37]

【参考译文】人们普遍认为,大理苏丹国统治下的地区比帝国控制下的地区安全得多,腐败现象也少得多。欧洲旅行者观察到,“这个国家一片平静”。[34] 商人“称赞白旗(大理控制的)地区的安全”,当地人将贸易繁荣归功于杜文秀的努力,“通过征收轻税和严格执法,尽可能多地进行贸易”。大理政府制定政策鼓励当地人保护商队,并命令官员守卫进入云南的主要通道,并为商人提供免费住宿。杜文秀本人在缅甸成立了一家贸易公司,并在阿瓦建立了两个棉花贸易局,其中一个由他的妹妹经营。[35][36] 宗教指示呼吁云南穆斯林和商人不要违反伊斯兰教法:[37]

“It is not permitted to transgress [the teaching of the legal schools by] acting [out of] subjective will; to foolishly [pursue] personal benefits; to despicably chase privileges; to act eccentrically or absurdly; to embrace heterodox [thoughts]; to claim supernatural [powers]; or to boast a connection with the spirits. Nor [it is permitted] to deceive common [people, in order to] pursue profit and fame; or to falsify rites and ceremonies, and to confuse different teachings. [This would be like] disguising [metals for] gold or counterfeiting silver; [or] selling dog meat [after] labeling [it] as “sheep”; [or] exaggerating [things] in order to deceive people. For those who fall prey to confusion, the harm is hard to undo. These kinds of things compromise cleanliness and truth [qingzhen], as do a poison or a big plague.”

【参考译文】“不可违背主观意志,不可愚昧地谋取私利,不可卑鄙地追求特权,不可荒唐离经,不可附庸,不可自称超自然,不可自夸鬼神,不可欺骗世人以求名利,不可伪造礼仪,不可混淆教义,就好比把金子伪造银子,把狗肉当作羊卖,不可夸大其词以欺骗世人。迷惑世人,其害难除,如毒药、大瘟疫,都是对清真不利的。”

These instructions indicate the Yunnanese Muslim concern for the preservation of Islamic Orthodoxy and their belief that Qing rule had corrupted their traditions with decadent habits and beliefs like Shamanism.[37]

【参考译文】这些指示表明云南穆斯林关心维护伊斯兰教正统派,他们认为清朝统治已经以萨满教等腐朽的习惯和信仰腐蚀了他们的传统。[37]

Islam, Confucianism and Tribal pagan animism were all legalized and “honoured” with a “Chinese-style bureaucracy” in Du Wenxiu’s sultanate. A third of the sultanate’s military posts were filled with Han Chinese, who also filled the majority of civil posts.[38]

【参考译文】在杜文秀统治的苏丹国,伊斯兰教、儒教和部落异教万物有灵论都合法化了,并被“尊崇”,并建立了“中国式官僚制度”。苏丹国三分之一的军事职位由汉人担任,大多数文职职位也由汉人担任。[38]

3. 评价

清亡后的国共两党均视杜文秀为革命英雄。在云南有许多纪念他的文物残存,如位于大理古城复兴路的杜文秀元帅府、位于大理镇下兑村的杜文秀墓。

4. 年号

李玉振《滇事述闻》称杜文秀在清咸丰六年(1856年)建伪号曰“全福”。[8]但根据大理下关地区出土的杜文秀时期的文物,杜文秀并没有用年号纪年,用干支纪年。[9]

A. 英文词条参考文献 | Notes

- ^ Qian, Jingyuan (2014). “Too Far from Mecca, Too Close to Peking: The Ethnic Violence and the Making of Chinese Muslim Identity, 1821-1871”. History Honors Projects. 27: 37.

- ^ 罗, 尔纲 (1980). “杜文秀”卖国”说辟谬”. Biology. S2CID 237200085.

- ^ Elleman, Bruce A. (2001). Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 64. ISBN 0415214734. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Fairbank, John King; Twitchett, Denis Crispin, eds. (1980). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 0521220297. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ “杜文秀” [Du Wenxiu]. www.shijiemingren.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 31 Mar 2017.[title missing]

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1089–1090. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ Schoppa, R. Keith (2008). East Asia: identities and change in the modern world, 1700-present (illustrated ed.). Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 58. ISBN 978-0132431460. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (1999). China’s Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Curzon Press. p. 59. ISBN 0700710264. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (2012). China: A Modern History (reprint ed.). I.B.Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 978-1780763811. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Atwill, David G. (2005). The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0804751595. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (1993). Asian Research Trends, Volumes 3-4. Tokyo, Japan: Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies. p. 137. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Mansfield, Stephen (2007). China, Yunnan Province. Compiled by Martin Walters (illustrated ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. p. 69. ISBN 978-1841621692. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Damian Harper (2007). China’s Southwest. Regional Guide Series (illustrated ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 223. ISBN 978-1741041859. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan N. (1998). Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China. Hong Kong University Press. p. 179. ISBN 9789622094680.

- ^ John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800–1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 213–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1096. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (1999). Rebellion south of the clouds: Ethnic insurgency, Muslim Yunnanese, and the Panthay rebellion. p. 315.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. pp. 105–106, 108.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. p. 120.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. pp. 117–118.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. pp. 125–126.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. pp. 127–128.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. pp. 129–130.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. p. 173.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. p. 154.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1090–1091. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1091. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ G. Atwill, Davud (1999). Rebellion south of the clouds: Ethnic insurgency, Muslim Yunnanese, and the Panthay rebellion. p. 300.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1091. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1092. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1089. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1093. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (1999). Rebellion south of the clouds: Ethnic insurgency, Muslim Yunnanese, and the Panthay rebellion. p. 296.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (1999). Rebellion south of the clouds: Ethnic insurgency, Muslim Yunnanese, and the Panthay rebellion. p. 298.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2005). The Chinese Sultanate Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. pp. 150–151.

- ^ CarneÌ, Louis de (1872). Travels in Indo-China and the Chinese empire. London, Chapman and Hall. pp. 319–320.

- ^ Tontini, Roberta (2016). Muslim Sanzijing: Shifts and Continuities in the Definition of Islam in China. Brill. pp. 129–130.

- ^ John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800–1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1099. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ Thant Myint-U. (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps: Histories of Burma. Macmillan. ISBN 0-374-16342-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Myint-U, Thant (2007). The River of Lost Footsteps: Histories of Burma. Macmillan. p. 145. ISBN 978-0374707903. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Myint-U, Thant (2012). Where China Meets India: Burma and the New Crossroads of Asia (illustrated, reprint ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 978-0374533526. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ White, Matthew (2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History (illustrated ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 298. ISBN 978-0393081923. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Cooke, Tim, ed. (2010). The New Cultural Atlas of China. Contributor Marshall Cavendish Corporation. Marshall Cavendish. p. 38. ISBN 978-0761478751. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ G. Atwill, Davi (1999). Rebellion south of the clouds: Ethnic insurgency, Muslim Yunnanese, and the Panthay rebellion. pp. 325–326.

- ^ G. Atwill, David (2003). “Blinkered Visions: Islamic Identity, Hui Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (4): 1099–1100. doi:10.2307/3591760. JSTOR 3591760. S2CID 161910411.

- ^ Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (1993). Asian Research Trends, Volumes 3-4. Tokyo, Japan: Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies. p. 136. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Giersch, Charles Patterson (2006). Asian Borderlands: The Transformation of Qing China’s Yunnan Frontier (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 217. ISBN 0674021711. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Mosk, Carl (2011). Traps Embraced Or Escaped: Elites in the Economic Development of Modern Japan and China. World Scientific. p. 62. ISBN 978-9814287524. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Comparative Civilizations Review, Issues 32-34. 1995. p. 36. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

B. 中文词条参考文献

- ^ 马颖生著. 马颖生史著论著选. 昆明: 云南民族出版社. 2006: 285–289. ISBN 7-5367-3406-9.

- ^ 刘晨. 杜文秀起义始末. 云南档案. 2012, (12): 29-31.

- ^ 罗尔纲. 回民起义杰出领袖杜文秀. 回族研究. 2009, 19 (3): 65-74.

- ^ 林荃著. 杜文秀起义研究. 昆明: 云南民族出版社. 2006: 20. ISBN 7-5367-3406-9.

- ^ 保山市社会科学界联合会编著;云南省社会科学界联合会组编. 保山史话. 昆明: 云南人民出版社. 2017: 80–82. ISBN 978-7-222-16673-8.

- ^ 杨怀中. 杜文秀传略. 回族研究. 2009, 19 (04): 15-23.

- ^ 钱汉江. 鲜为人知的杜文秀起义:秀才造反捅开清廷大窟窿. 人民网. 2014-08-07. (原始内容存档于2020-09-20).

- ^ 李玉振《滇事述闻》卷上:咸丰六年七月间,……文秀既出,倍道趋蒙化,率所募援姚回匪夷数千,袭据大理,共推为总统兵马大元帅,僭伪号曰“全福”。

- ^ 肖娜. 杜文秀起義研究. 兰州: 兰州大学硕士学位论文. 2009: 23.

C. 外部链接

Wikiquote has quotations related to Du Wenxiu.

【参考译文】维基语录中有与杜文秀相关的语录。

- 白寿彝. 杜大元帅墓碑(1985年)

. 回族研究. 2009, 19 (4): 13–14 [2023-01-20]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-20).

. 回族研究. 2009, 19 (4): 13–14 [2023-01-20]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-20). - 杜文秀墓和杜文秀元帅府旧址

- 谁是卖国贼:杜文秀“卖国”案真相 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

分享到: