中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。

关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及根据名称精确检索已搬运的词条,请点击这里访问辽观网站。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

目录

1. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

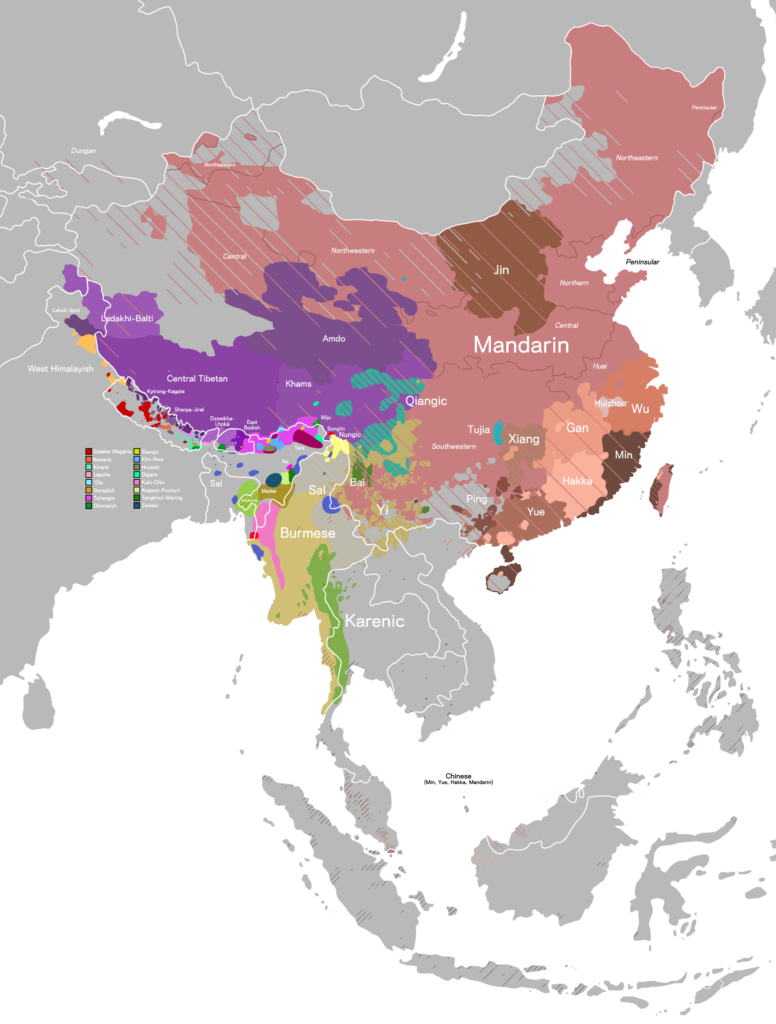

图片题注:汉藏语系分布图: 汉语族(红色)、 藏语群(紫色)、 缅彝语群(黄色)、 克伦语支(绿色)

图片来源:GalaxMaps

Sino-Tibetan (also referred to as Trans-Himalayan)[1][2] is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers.[3] Around 1.4 billion people speak a Sino-Tibetan language.[4] The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Sinitic languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages with large numbers of speakers include Burmese (33 million) and the Tibetic languages (6 million). Four United Nations member states (China, Singapore, Myanmar, and Bhutan) have a Sino-Tibetan language as a main native language. Other languages of the family are spoken in the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Most of these have small speech communities in remote mountain areas, and as such are poorly documented.

【参考译文】汉藏语系(也被称为跨喜马拉雅语系)[1][2]包含400多种语言,其母语使用者数量仅次于印欧语系。[3]约有14亿人使用汉藏语系语言。[4]其中绝大多数为13亿使用汉语族语言的母语者。其他拥有大量使用者的汉藏语系语言包括缅甸语(3300万使用者)和藏缅语族语言(600万使用者)。有四个联合国成员国(中国、新加坡、缅甸和不丹)将汉藏语系语言作为主要母语。该语系的其他语言分布于喜马拉雅山脉、东南亚高原以及青藏高原东缘。其中大多数语言的使用群体较小,分布在偏远的山区,因此相关记录较少。

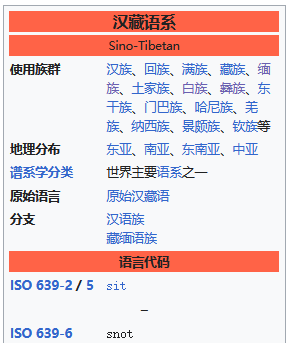

汉藏语系(英语:Sino-Tibetan languages),也称跨喜马拉雅语系(英语:Trans-Himalayan languages),是世界主要语系之一,但是划分的形式很多,这个语系至少包含汉语族和藏缅语族,共计约400种语言,底下的包含汉语(官话)、粤语、藏语、缅语、彝语等,主要分布在中国大陆、港澳地区、台湾、缅甸、不丹、尼泊尔、印度、新加坡、马来西亚等亚洲各国和地区。以汉藏语系语言为母语的人口约有15亿[1]。按使用人数计算,是仅次于印欧语系的第二大语系。

Several low-level subgroups have been securely reconstructed, but reconstruction of a proto-language for the family as a whole is still at an early stage, so the higher-level structure of Sino-Tibetan remains unclear. Although the family is traditionally presented as divided into Sinitic (i.e. Chinese languages) and Tibeto-Burman branches, a common origin of the non-Sinitic languages has never been demonstrated. The Kra–Dai and Hmong–Mien languages are generally included within Sino-Tibetan by Chinese linguists but have been excluded by the international community since the 1940s. Several links to other language families have been proposed, but none have broad acceptance.

【参考译文】虽然已经可靠地重构了几个低层次的子群,但整个语系的原始语言重构仍处于初级阶段,因此汉藏语系的高层结构仍然不明确。尽管传统上将该语系划分为汉语族(即中文语言)和藏缅语族两大分支,但非汉语族语言的共同起源从未得到证实。中国的语言学家通常将侗台语系和苗瑶语系纳入汉藏语系,但自20世纪40年代以来,国际社会一直将它们排除在外。尽管有人提出了与其他语系存在联系的几种说法,但均未得到广泛认可。

2. 历史(学术史)| History

A genetic relationship between Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese, and other languages was first proposed in the early 19th century and is now broadly accepted. The initial focus on languages of civilizations with long literary traditions has been broadened to include less widely spoken languages, some of which have only recently, or never, been written. However, the reconstruction of the family is much less developed than for families such as Indo-European or Austroasiatic. Difficulties have included the great diversity of the languages, the lack of inflection in many of them, and the effects of language contact. In addition, many of the smaller languages are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to reach and are often also sensitive border zones.[5] There is no consensus regarding the date and location of their origin.[6]

【参考译文】汉语、藏语、缅甸语和其他语言之间存在亲缘关系的说法最早于19世纪初被提出,现在这一观点已被广泛接受。起初,研究重点集中在具有悠久文学传统的文明所使用的语言上,现在已扩大到包括使用范围较小的语言,其中一些语言最近才被书写,甚至从未被书写过。然而,与印欧语系或南岛语系等语系相比,汉藏语系的重建工作进展得并不顺利。其中的困难包括语言多样性大、许多语言缺乏词形变化以及语言接触的影响。此外,许多使用范围较小的语言分布在难以到达的山区,而这些地区往往也是敏感的边境地区。[5]关于这些语言的起源时间和地点,尚未达成共识。[6]

德国学者朱利斯·克拉普罗特早在1823年就提出汉语、藏语、缅甸语的基础词汇之间有同源关系,而泰语和越南语则不同。但后来他的著作被淡忘了,一直到20世纪,学者们才重新重视他的研究。

2.1 早期工作 | Early work

During the 18th century, several scholars noticed parallels between Tibetan and Burmese, both languages with extensive literary traditions. Early in the following century, Brian Houghton Hodgson and others noted that many non-literary languages of the highlands of northeast India and Southeast Asia were also related to these. The name “Tibeto-Burman” was first applied to this group in 1856 by James Richardson Logan, who added Karen in 1858.[7][8] The third volume of the Linguistic Survey of India, edited by Sten Konow, was devoted to the Tibeto-Burman languages of British India.[9]

【参考译文】18世纪时,几位学者注意到藏语和缅甸语之间存在相似之处,这两种语言都有着悠久的文学传统。在接下来的世纪初,布莱恩·霍顿·霍奇森(Brian Houghton Hodgson)和其他人指出,印度东北部和东南亚高地地区的许多非文学语言也与这两种语言有关。1856年,詹姆斯·理查德森·洛根(James Richardson Logan)首次将“藏缅语族”这一名称应用于这一语群,并在1858年将克钦语(Karen)也归入其中。[7][8]由斯特恩·科诺(Sten Konow)编辑的《印度语言调查》(Linguistic Survey of India)第三卷专门探讨了英国印度地区的藏缅语族语言。[9]

Studies of the “Indo-Chinese” languages of Southeast Asia from the mid-19th century by Logan and others revealed that they comprised four families: Tibeto-Burman, Tai, Mon–Khmer and Malayo-Polynesian. Julius Klaproth had noted in 1823 that Burmese, Tibetan, and Chinese all shared common basic vocabulary but that Thai, Mon, and Vietnamese were quite different.[10][11] Ernst Kuhn envisaged a group with two branches, Chinese-Siamese and Tibeto-Burman.[a] August Conrady called this group Indo-Chinese in his influential 1896 classification, though he had doubts about Karen. Conrady’s terminology was widely used, but there was uncertainty regarding his exclusion of Vietnamese. Franz Nikolaus Finck in 1909 placed Karen as a third branch of Chinese-Siamese.[12][13]

【参考译文】从19世纪中叶开始,洛根(Logan)和其他人对东南亚的“印中”语言进行研究,发现它们包含四个语系:藏缅语族、侗台语系、孟-高棉语系和马来-波利尼西亚语系。尤利乌斯·克拉普罗特(Julius Klaproth)于1823年指出,缅甸语、藏语和汉语都有共同的基本词汇,但泰语、孟语和越南语则截然不同。[10][11]恩斯特·库恩(Ernst Kuhn)设想了一个包含两个分支的语系,即汉-暹罗语支和藏缅语支。[a]奥古斯特·康拉德(August Conrady)在他1896年具有影响力的分类中将这一语系称为印中语系,尽管他对克钦语持怀疑态度。康拉德的术语被广泛使用,但对于他将越南语排除在外这一点存在不确定性。1909年,弗兰茨·尼古拉斯·芬克(Franz Nikolaus Finck)将克钦语列为汉-暹罗语支的第三个分支。[12][13]

【英文词条原注a】Kuhn (1889), p. 189: “wir das Tibetisch-Barmanische einerseits, das Chinesisch-Siamesische anderseits als deutlich geschiedene und doch wieder verwandte Gruppen einer einheitlichen Sprachfamilie anzuerkennen haben.” (also quoted in van Driem (2001), p. 264.)

【参考译文】Kuhn (1889),第 347 页189:“我们必须认识到,藏-巴曼语系和汉-暹罗语系是两个截然不同但又相互关联的统一语系群体。” (也引自 van Driem (2001),第 264 页。)

Jean Przyluski introduced the French term sino-tibétain as the title of his chapter on the group in Meillet and Cohen‘s Les langues du monde in 1924.[14][15] He divided them into three groups: Tibeto-Burman, Chinese and Tai,[14] and was uncertain about the affinity of Karen and Hmong–Mien.[16] The English translation “Sino-Tibetan” first appeared in a short note by Przyluski and Luce in 1931.[17]

【参考译文】1924年,让·普日卢斯基(Jean Przyluski)在梅耶(Meillet)和科恩(Cohen)合著的《世界语言》(Les langues du monde)一书中,用法语术语“sino-tibétain”作为他关于该语族的章节标题。[14][15]他将这一语族分为三个组:藏缅语组、汉语组和侗台语组,[14]并且对于克钦语和苗瑶语的亲缘关系表示不确定。[16]“Sino-Tibetan”(汉藏语系)的英文翻译首次出现在普日卢斯基和卢斯(Luce)于1931年发表的一篇短文中。[17]

19世纪流行的分类,一般都是出于人种的考量,例如内森·布朗(Nathan Brown)在1837年提出“印度支那语”的概念,用来表示除阿尔泰语和达罗毗荼语以外的所有东方语言,包括日语和南岛语。

“汉藏语”一词是普祖鲁斯基(Jean Przyluski)在1924年提出的,他的分类如下:

在此基础上,有人把汉语、侗台语和苗瑶语分开,这种分类在中国比较流行:

20世纪后期,多数西方学者从汉藏语中排除了侗台语和苗瑶语,但是保留了汉语和藏缅语的二分法,例如马蒂索夫(Matisoff)、布拉德利(Bradley 1997)、杜冠明(Thurgood 2003)的分类:

目前有学者不认同这种二分法。更有人认为汉语在汉藏谱系树的地位可能比较接近藏语,反而汉语和缅甸语或者羌语的关系没有那么密切。例如Van Driem(2001)就把汉语和藏语并称汉藏语族,作为汉藏缅语系的一个分支。

2.2 沙菲尔和本尼迪克特 | Shafer and Benedict

In 1935, the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber started the Sino-Tibetan Philology Project, funded by the Works Project Administration and based at the University of California, Berkeley.[18] The project was supervised by Robert Shafer until late 1938, and then by Paul K. Benedict. Under their direction, the staff of 30 non-linguists collated all the available documentation of Sino-Tibetan languages. The result was eight copies of a 15-volume typescript entitled Sino-Tibetan Linguistics.[9][b] This work was never published but furnished the data for a series of papers by Shafer, as well as Shafer’s five-volume Introduction to Sino-Tibetan and Benedict’s Sino-Tibetan, a Conspectus.[20][21]

【参考译文】1935年,人类学家阿尔弗雷德·克罗伯(Alfred Kroeber)启动了汉藏语语文学项目,该项目由美国工程振兴局资助,基地设在加利福尼亚大学伯克利分校。[18]该项目自1938年末之前由罗伯特·沙菲尔(Robert Shafer)负责监督,之后由保罗·K·本尼迪克特(Paul K. Benedict)接手。在他们的指导下,30名非语言学家的工作人员整理了所有能找到的汉藏语系语言资料。最终成果是八套15卷的打字稿,名为《汉藏语言学》。[9][b]这项工作从未出版过,但它为沙菲尔的一系列论文以及他的五卷本《汉藏语导论》和本尼迪克特的《汉藏语概览》提供了数据。[20][21]

【英文词条原注b】The volumes were: 1. Introduction and bibliography, 2. Bhotish, 3. West Himalayish, 4. West Central Himalayish, 5. East Himalayish, 6. Digarish, 7. Nungish, 8. Dzorgaish, 9. Hruso, 10. Dhimalish, 11. Baric, 12. Burmish–Lolish, 13. Kachinish, 14. Kukish, 15. Mruish.[19]

【参考译文】这些卷分别是:1. 引言和参考书目,2. 博蒂什语,3. 西喜马拉雅语,4. 中西喜马拉雅语,5. 东喜马拉雅语,6. 迪加里什语,7. 努格什语,8. 佐尔盖语,9. 赫鲁索语,10. 迪马利什语,11. 巴里克语,12. 缅甸语–洛里什语,13. 卡奇语,14. 库基什语,15. 姆鲁什语。[19]

Benedict completed the manuscript of his work in 1941, but it was not published until 1972.[22] Instead of building the entire family tree, he set out to reconstruct a Proto-Tibeto-Burman language by comparing five major languages, with occasional comparisons with other languages.[23] He reconstructed a two-way distinction on initial consonants based on voicing, with aspiration conditioned by pre-initial consonants that had been retained in Tibetic but lost in many other languages.[24] Thus, Benedict reconstructed the following initials:[25]

【参考译文】本尼迪克特于1941年完成了他的著作手稿,但直到1972年才出版。[22]他没有构建整个语系的家谱,而是通过比较五种主要语言(偶尔与其他语言进行比较)来重建原始藏缅语。[23]他根据送气与否重建了辅音音首的二元对立,送气条件取决于在藏语中保留但在许多其他语言中丢失的前辅音音首。[24]因此,本尼迪克特重建了以下辅音音首:[25]

| TB | Tibetan 【藏语】 | Jingpho 【景颇语】 | Burmese 【缅语】 | Garo 【加罗语】 | Mizo 【米佐语】 | S’gaw Karen 【斯戈语】 | Old Chinese[c] 【古汉语】 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *k | k(h) | k(h) ~ g | k(h) | k(h) ~ g | k(h) | k(h) | *k(h) |

| *g | g | g ~ k(h) | k | g ~ k(h) | k | k(h) | *gh |

| *ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | y | *ŋ |

| *t | t(h) | t(h) ~ d | t(h) | t(h) ~ d | t(h) | t(h) | *t(h) |

| *d | d | d ~ t(h) | t | d ~ t(h) | d | d | *dh |

| *n | n | n | n | n | n | n | *n ~ *ń |

| *p | p(h) | p(h) ~ b | p(h) | p(h) ~ b | p(h) | p(h) | *p(h) |

| *b | b | b ~ p(h) | p | b ~ p(h) | b | b | *bh |

| *m | m | m | m | m | m | m | *m |

| *ts | ts(h) | ts ~ dz | ts(h) | s ~ tś(h) | s | s(h) | *ts(h) |

| *dz | dz | dz ~ ts ~ ś | ts | tś(h) | f | s(h) | ? |

| *s | s | s | s | th | th | θ | *s |

| *z | z | z ~ ś | s | s | f | θ | ? |

| *r | r | r | r | r | r | γ | *l |

| *l | l | l | l | l | l | l | *l |

| *h | h | ∅ | h | ∅ | h | h | *x |

| *w | ∅ | w | w | w | w | w | *gjw |

| *y | y | y | y | tś ~ dź | z | y | *dj ~ *zj |

【英文词条原注&表内注c】Karlgren’s reconstruction, with aspiration as ‘h’ and ‘i̯’ as ‘j’ to aid comparison.

【参考译文】参考译文:高本汉(Karlgren)在重构时,将送气音表示为“h”,将“i̯”表示为“j”,以便于比较。

Although the initial consonants of cognates tend to have the same place and manner of articulation, voicing and aspiration are often unpredictable.[26] This irregularity was attacked by Roy Andrew Miller,[27] though Benedict’s supporters attribute it to the effects of prefixes that have been lost and are often unrecoverable.[28] The issue remains unsolved today.[26] It was cited together with the lack of reconstructable shared morphology, and evidence that much shared lexical material has been borrowed from Chinese into Tibeto-Burman, by Christopher Beckwith, one of the few scholars still arguing that Chinese is not related to Tibeto-Burman.[29][30]

【参考译文】尽管同源词的辅音音首往往具有相同的发音部位和发音方式,但清浊和送气往往难以预测。[26]罗伊·安德鲁·米勒(Roy Andrew Miller)对这种不规则性提出了质疑,[27]不过本尼迪克特的支持者认为这是由于已经丢失且通常无法恢复的前缀所产生的影响。[28]这个问题至今仍未解决。[26]克里斯托弗·贝克威思(Christopher Beckwith)是少数几位仍认为汉语与藏缅语无亲缘关系的学者之一,他引用了这一点,以及缺乏可重建的共享形态学证据,和大量共享词汇材料是从汉语借入藏缅语的证据。[29][30]

Benedict also reconstructed, at least for Tibeto-Burman, prefixes such as the causative s-, the intransitive m-, and r-, b- g- and d- of uncertain function, as well as suffixes -s, -t and -n.[31]

【参考译文】本尼迪克特还至少为藏缅语重构了诸如使役前缀s-、不及物前缀m-,以及功能不确定的r-、b-、g-和d-等前缀,以及后缀-s、-t和-n。[31]

2.3 对文学语言的研究 | Study of literary languages

Old Chinese is by far the oldest recorded Sino-Tibetan language, with inscriptions dating from around 1250 BC and a huge body of literature from the first millennium BC. However, the Chinese script is logographic and does not represent sounds systematically; it is therefore difficult to reconstruct the phonology of the language from the written records. Scholars have sought to reconstruct the phonology of Old Chinese by comparing the obscure descriptions of the sounds of Middle Chinese in medieval dictionaries with phonetic elements in Chinese characters and the rhyming patterns of early poetry. The first complete reconstruction, the Grammata Serica Recensa of Bernard Karlgren, was used by Benedict and Shafer.[32]

【参考译文】古汉语是目前为止有记录的最古老的汉藏语系语言,其铭文可追溯至约公元前1250年,且公元前一千年间留下了大量的文献资料。然而,汉字是表意文字,不能系统地表示读音;因此,很难从书面记录中重建这种语言的音韵体系。学者们试图通过比较中世纪字典中对中古汉语发音的模糊描述、汉字中的音韵成分以及早期诗歌的押韵模式来重建古汉语的音韵体系。伯纳德·高本汉(Bernard Karlgren)的《汉文典》(Grammata Serica Recensa)是首次完整的重建尝试,并被本尼迪克特(Benedict)和沙菲尔(Shafer)所采用。[32]

Karlgren’s reconstruction was somewhat unwieldy, with many sounds having a highly non-uniform distribution. Later scholars have revised it by drawing on a range of other sources.[33] Some proposals were based on cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages, though workers have also found solely Chinese evidence for them.[34] For example, recent reconstructions of Old Chinese have reduced Karlgren’s 15 vowels to a six-vowel system originally suggested by Nicholas Bodman.[35] Similarly, Karlgren’s *l has been recast as *r, with a different initial interpreted as *l, matching Tibeto-Burman cognates, but also supported by Chinese transcriptions of foreign names.[36] A growing number of scholars believe that Old Chinese did not use tones and that the tones of Middle Chinese developed from final consonants. One of these, *-s, is believed to be a suffix, with cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages.[37]

【参考译文】高本汉的重建方案略显笨拙,许多发音的分布极不均匀。后来的学者通过借鉴一系列其他资料对其进行了修订。[33]一些提议是基于其他汉藏语系语言的同源词,尽管研究人员也发现了仅基于汉语的证据。[34]例如,最近的古汉语重建将高本汉的15个元音减少到了尼古拉斯·博德曼(Nicholas Bodman)最初提出的六个元音系统。[35]同样,高本汉的*l被重新定义为*r,而另一个不同的辅音音首被解释为*l,这与藏缅语的同源词相匹配,同时也得到了汉语对外国人名音译的支持。[36]越来越多的学者认为,古汉语不使用声调,而中古汉语的声调是从韵尾辅音发展而来的。其中之一,-s,被认为是一个后缀,在其他汉藏语系语言中有同源词。[37]

Tibetic has extensive written records from the adoption of writing by the Tibetan Empire in the mid-7th century. The earliest records of Burmese (such as the 12th-century Myazedi inscription) are more limited, but later an extensive literature developed. Both languages are recorded in alphabetic scripts ultimately derived from the Brahmi script of Ancient India. Most comparative work has used the conservative written forms of these languages, following the dictionaries of Jäschke (Tibetan) and Judson (Burmese), though both contain entries from a wide range of periods.[38]

【参考译文】自7世纪中叶吐蕃帝国采用文字以来,藏语就有了大量的书面记录。缅甸语的最早记录(如12世纪的《迈扎迪碑铭》)较为有限,但后来也发展出了丰富的文献。这两种语言的记录都采用了最终源自古代印度婆罗米字母的字母文字。大多数比较研究工作都使用了这些语言的保守书面形式,遵循雅施克(Jäschke,针对藏语)和朱德森(Judson,针对缅甸语)的字典,尽管这两本字典都包含了来自不同时期的广泛条目。[38]

There are also extensive records in Tangut, the language of the Western Xia (1038–1227). Tangut is recorded in a Chinese-inspired logographic script, whose interpretation presents many difficulties, even though multilingual dictionaries have been found.[39][40]

【参考译文】西夏文(西夏国1038–1227年的语言)也有大量的记录。西夏文采用了一种受汉字启发的表意文字,尽管已经发现了多语字典,但其解读仍面临许多困难。[39][40]

Gong Hwang-cherng has compared Old Chinese, Tibetic, Burmese, and Tangut to establish sound correspondences between those languages.[23][41] He found that Tibetic and Burmese /a/ correspond to two Old Chinese vowels, *a and *ə.[42] While this has been considered evidence for a separate Tibeto-Burman subgroup, Hill (2014) finds that Burmese has distinct correspondences for Old Chinese rhymes -ay : *-aj and -i : *-əj, and hence argues that the development *ə > *a occurred independently in Tibetan and Burmese.[43]

【参考译文】龚煌城比较了古汉语、藏语、缅甸语和西夏文,以建立这些语言之间的语音对应关系。[23][41]他发现藏语和缅甸语的/a/对应于古汉语的两个元音,a和ə。[42]虽然这曾被视为藏缅语亚组独立的证据,但希尔(Hill,2014年)发现,缅甸语与古汉语韵脚-ay对应为*-aj,-i对应为*-əj,因此他认为*ə > *a的演变在藏语和缅甸语中是独立发生的。[43]

2.4 田野调查 | Fieldwork

The descriptions of non-literary languages used by Shafer and Benedict were often produced by missionaries and colonial administrators of varying linguistic skills.[44][45] Most of the smaller Sino-Tibetan languages are spoken in inaccessible mountainous areas, many of which are politically or militarily sensitive and thus closed to investigators. Until the 1980s, the best-studied areas were Nepal and northern Thailand.[46] In the 1980s and 1990s, new surveys were published from the Himalayas and southwestern China. Of particular interest was the increasing literature on the Qiangic languages of western Sichuan and adjacent areas.[47][48]

【参考译文】沙菲尔(Shafer)和本尼迪克特(Benedict)所使用的非文学语言的描述,往往出自具有不同语言技能的传教士和殖民官员之手。[44][45]大多数较小的汉藏语系语言都使用在难以到达的山区,其中许多地区由于政治或军事上的敏感性而对调查人员封闭。直到20世纪80年代,研究最为透彻的地区是尼泊尔和泰国北部。[46]20世纪80年代和90年代,喜马拉雅山脉和中国西南部地区发表了新的调查报告。尤其值得关注的是,关于四川西部及其邻近地区羌语支语言的文献日益增多。[47][48]

1.5 与其他语系的关系

- 沙加尔认为汉藏语系和南岛语系有发生学关系,提出汉-南岛超语系,在该观点下,汉藏语系、苗瑶语系、壮侗语系、南亚语系、南岛语系同源。

- 高晶一与特努·田德尔提出了汉-乌拉尔语系,该假说认为汉藏语系与乌拉尔语系存在发生学关系。

- 斯塔罗斯金提出了德内-高加索超语系,该假说认为汉藏语系与巴斯克语、西北高加索语系、东北高加索语系、布鲁夏斯基语、叶尼塞语系、纳-德内语系、海达语等存在发生学关系。

- 孔好古提出了汉藏-印欧语系,该假说认为汉藏语系 与印欧语系存在发生学关系。

但这些观点都不被主流的语言学者接受。

3. 同源词汇

See also: Old Chinese § Classification【参见:“古汉语”词条的“分类”章节】

See also: Proto-Sino-Tibetan language § Vocabulary【参见:“原始汉藏语”词条的“词汇”章节】

汉藏语系各语言之间存在很多同源词,由于原始汉藏语的分化经历了很长时间,对于原始汉藏语的拟构,学术上也存在不同的观点。另外汉字在表音方面的不足,使得原始汉语的拟构存在多种版本,下表给出了一个汉藏语系各语言之间的同源词。

| 基数词[36] | 原始汉藏语 | 闽南语 | 客家语 | 上海话 | 普通话 | 上古汉语 | 原始藏语 | 藏语 | 原始克伦语 | 原始缅甸语 | 原始克钦(景颇)语 | 原始喜马拉雅语 | 原始博多-加罗语 | 原始库基语 | 原始那加语 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘1’ | *k-tyig | it̚ | it̚ | ɪʔ | ji | *yit(独*dok) | g-cig | ɡt͡ɕiɡ | *teg | *t’i | *se | *k’at | *k’at | ||

| ‘2’ | *k-nyis | d͡ʑ̥i | nʲi | əl̴/nʲi | ɚ | *nyis | *g-nis | ɡnʲis | *k’-ni | *-n’i | *nis | *g-ni | *-ni | *k’ni | |

| ‘3’ | *k-t’um | sam/sã | sam | se̞ | san | *sum | *sum | ɡsum | *g-sum | *som | *sum | *sum | *g-tam | *-t’um | *k-t’um |

| ‘4’ | *p-li | su/ɕi | ɕi | sɨ | sɨ | *s-yiy | *b-liy | bʑi | *wir | *p-li | *(p)li | *bri | *-li | *p-li | |

| ‘5’ | *p-ŋa *l-ŋa | ŋo/g̥o | ŋ̩ | u/ŋ̩ | wu | *ŋaʔ | *lŋya | lŋa | *ŋaʔ | *ŋa | *p-ŋa | *p-ŋa | *b-ŋa | *p-ŋa *r-ŋa | *p’-ŋa |

| ‘6’ | *t-r’uk *k-r’uk | liok̚/lak̚ | liʊk̚ | loʔ | lioʊ̯ | *C-r’uk | *d-ruk | dɹuɡ | *xru | *khyok | *k-ru | *t-ruk | *(k)rōk | *k-rūk *p-rūk | *t-rūk |

| ‘7’ | *s-Nis | t͡ɕʰit̚ | t͡ɕʰit̚ | t͡ɕʰɪʔ | t͡ɕʰi | *tshyit | *s-nis | bdyn | *-nøy | *nit | *s-nit | *nis- | *s-ni | *s-ni | *š-ni |

| ‘8’ | *t-r’iat | pat̚/pueʔ | pat̚ | päʔ | pa | *p-ret | *b-r-gyat | bɹɡɹjɛd | *xroq | *slit | *-šiat | *žyad | *čat | *t-riat | *-šot |

| ‘9’ | *t-kua | kiu/kau | kiu | t͡ɕiɤ | t͡ɕioʊ̯ | *kwyuʔ | *d-kuw | dɡu | *gu- | *ko | *t-ku | *gu | *t-ku | *t-ku | *t-ko |

| ’10’ | *-tsi(?) | ɕip̚/t͡sap̚ | sɨp̚ | z̥əʔ | ʂɨ | *gyip | *tsi(y) | bt͡ɕu | *ts’i | *tše | *t-tsel | *tšī | *t-tši | *tsom(?) |

Sino-Tibetan numerals【汉藏语系的数字】

| gloss 【基数词】 | Old Chinese[118] 【古汉语】 | Old Tibetan[119] 【古藏语】 | Old Burmese[119] 【古缅语】 | Jingpho[120] 【景颇语】 | Garo[120] 【加罗语】 | Limbu[121] 【林布语】 | Kanauri[122] 【金瑙里语】 | Tujia[123] 【土家语】 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “one” | 一 *ʔjit | – | ac | – | sa | – | id | – |

| 隻 *tjek “single” | gcig | tac | – | thik | – | – | ||

| “two” | 二 *njijs | gnyis | nhac | – | gini | nɛtchi | niš | ne⁵⁵ |

| “three” | 三 *sum | gsum | sumḥ | mə̀sūm | gittam | sumsi | sum | so⁵⁵ |

| “four” | 四 *sjijs | bzhi | liy | mə̀lī | bri | lisi | pə: | ze⁵⁵ |

| “five” | 五 *ŋaʔ | lnga | ṅāḥ | mə̀ŋā | boŋa | nasi | ṅa | ũ⁵⁵ |

| “six” | 六 *C-rjuk | drug | khrok | krúʔ | dok | tuksi | țuk | wo²¹ |

| “seven” | 七 *tsʰjit | – | khu-nac | sə̀nìt | sini | nusi | štiš | ne²¹ |

| “eight” | 八 *pret | brgyad | rhac | mə̀tshát | chet | yɛtchi | rəy | je²¹ |

| “nine” | 九 *kjuʔ | dgu | kuiḥ | cə̀khù | sku[124] | sku | sgui | kɨe⁵⁵ |

| “ten” | 十 *gjəp | – | kip[125] | – | – | gip | – | – |

| – | bcu | chay | shī | chikuŋ | – | səy | – |

4. 分布 | Distribution

Most of the current spread of Sino-Tibetan languages is the result of historical expansions of the three groups with the most speakers – Chinese, Burmese and Tibetic – replacing an unknown number of earlier languages. These groups also have the longest literary traditions of the family. The remaining languages are spoken in mountainous areas, along the southern slopes of the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau.

【参考译文】汉藏语系当今的分布范围,很大程度上是由于汉语、缅甸语和藏语这三大使用人数最多的语群在历史上不断扩张,取代了数量不详的早期语言。这些语群还拥有汉藏语系中最悠久的文学传统。其余的语言则分布在喜马拉雅山脉南坡、东南亚高地和青藏高原东缘的山区。

汉藏语系的语言主要分布在中国大陆、港澳地区、台湾、缅甸、印度北部喜马拉雅山南麓和东北部、尼泊尔、不丹等地[1]。汉藏语系已知有400多种语言,其中,汉语、藏语和缅甸语占据了绝大多数人口及分布区域,而其余语言则大多分布在山区,沿喜马拉雅山脉南坡、东南亚地块和青藏高原东缘等地 [1]。

汉藏语系的语言内部差异非常大。在语法方面,多数汉藏语都是主语-宾语-谓语的语序,比如“我饭吃”,只有汉语、白语和克伦语支是主语-谓语-宾语的语序,如是“我吃饭”[1]。语音上多样性也很强,有些语言拥有8个以上声调,也有的没有声调[1]。

4.1 当代语言 | Contemporary languages

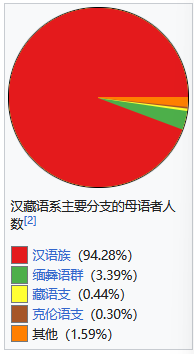

图片题注:Distribution of the larger branches of Sino-Tibetan, with proportion of first-language speakers:[49] Orange – Sinitic (94.3%) Purple – Lolo–Burmese (3.4%) Blue – Tibetic (0.4%) Green – Karenic (0.3%) Red – others (1.6%)

参考译文:汉藏语系各大语支以第一语言使用者的比例分布如下:[49]

橙色 – 汉语支(94.3%)

紫色 – 缅彝语支(3.4%)

蓝色 – 藏语支(0.4%)

绿色 – 克伦语支(0.3%)

红色 – 其他(1.6%)

图片来源:Kanguole

The branch with the largest number of speakers by far is the Sinitic languages, with 1.3 billion speakers, most of whom live in the eastern half of China.[50] The first records of Chinese are oracle bone inscriptions from c. 1250 BC, when Old Chinese was spoken around the middle reaches of the Yellow River.[51] Chinese has since expanded throughout China, forming a family whose diversity has been compared with the Romance languages. Diversity is greater in the rugged terrain of southeast China than in the North China Plain.[52]

【参考译文】到目前为止,使用人数最多的语支是汉语支,有13亿使用者,其中大多数居住在中国东部。[50]关于汉语的最早记录是约公元前1250年的甲骨文,当时古汉语在黄河中下游地区使用。[51]自此以后,汉语遍布中国各地,形成了一个语族,其多样性可与罗曼语族相媲美。中国东南部的崎岖地形中语言的多样性要大于华北平原。[52]

Burmese is the national language of Myanmar, and the first language of some 33 million people.[53] Burmese speakers first entered the northern Irrawaddy basin from what is now western Yunnan in the early ninth century, in conjunction with an invasion by Nanzhao that shattered the Pyu city-states.[54] Other Burmish languages are still spoken in Dehong Prefecture in the far west of Yunnan.[55] By the 11th century, their Pagan Kingdom had expanded over the whole basin.[54] The oldest texts, such as the Myazedi inscription, date from the early 12th century.[55] The closely related Loloish languages are spoken by 9 million people in the mountains of western Sichuan, Yunnan, and nearby areas in northern Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam.[56][49]

【参考译文】缅甸语是缅甸的国语,也是大约3300万人的第一语言。[53]9世纪初,随着南诏入侵并摧毁骠国城邦,缅甸语使用者首次从现在的云南西部进入伊洛瓦底江盆地北部。[54]在云南最西部的德宏州,人们仍然说着其他属于缅甸语支的语言。[55]到了11世纪,缅甸的蒲甘王朝已经扩张到整个伊洛瓦底江盆地。[54]最古老的文献,如《迈扎迪碑铭》,可追溯到12世纪初。[55]约有900万人使用与缅甸语支密切相关的彝语支语言,他们分布在四川西部、云南的山地以及缅甸北部、泰国、老挝和越南的邻近地区。[56][49]

云南西端的德宏州仍使用其他缅语支语言。[5]:195 到11世纪,他们的蒲甘王朝已经扩张到了整个盆地。[4]:165 摩耶佛塔碑文等早期文本可以追溯至12世纪早期。[5]:195

The Tibetic languages are spoken by some 6 million people on the Tibetan Plateau and neighbouring areas in the Himalayas and western Sichuan.[57] They are descended from Old Tibetan, which was originally spoken in the Yarlung Valley before it was spread by the expansion of the Tibetan Empire in the seventh century.[58] Although the empire collapsed in the ninth century, Classical Tibetan remained influential as the liturgical language of Tibetan Buddhism.[59]

【参考译文】藏语支语言由大约600万人使用,他们分布在青藏高原以及喜马拉雅山脉和四川西部的邻近地区。[57]藏语支语言源自古藏语,古藏语最初在雅鲁藏布江流域使用,后来在7世纪随着吐蕃帝国的扩张而传播开来。[58]尽管吐蕃帝国在9世纪崩溃,但古典藏语作为藏传佛教的礼仪语言,仍然具有影响力。[59]

The remaining languages are spoken in upland areas. Southernmost are the Karen languages, spoken by 4 million people in the hill country along the Myanmar–Thailand border, with the greatest diversity in the Karen Hills, which are believed to be the homeland of the group.[60] The highlands stretching from northeast India to northern Myanmar contain over 100 highly diverse Sino-Tibetan languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages are found along the southern slopes of the Himalayas and the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau.[61] The 22 official languages listed in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India include only two Sino-Tibetan languages, namely Meitei (officially called Manipuri) and Bodo.

【参考译文】其余的语言则在高地地区使用。最南端的是克伦语,有400万人在缅甸与泰国边境的丘陵地带使用,其中克伦丘陵地区的克伦语最为多样,据信这里是克伦人的故乡。[60]从印度东北部延伸至缅甸北部的高原地区,存在着100多种高度多样化的汉藏语系语言。其他汉藏语系语言则分布在喜马拉雅山脉南坡和青藏高原东缘。[61]印度《宪法》第八附表中列出的22种官方语言中,只有两种是汉藏语系语言,即梅泰语(官方称为曼尼普尔语)和博多语。

4.2 起源与扩散 | Homeland

语言学家对汉藏语系内部各语支亲缘关系、分化时间以及原乡所在长期存在争议,反映出对系属分类和时间深度的不确定[8]:423[1]。在语言分类里,传统上把汉藏语系中汉语之外的其它语言统称作藏缅语族。然而,因为汉藏语系语言之间差异很大,又缺乏历史文献材料,汉藏语的早期历史,以及汉藏语系各语支之间的亲疏关系在学者之间有很多争议[1][10]:468-498[11]:71-104。

早期学者一般认为汉藏语系分为四个语族,即汉语族、藏缅语族、壮侗语族、苗瑶语族。1970年代以后,西方学者一般认为苗瑶语系和壮侗语系不属于汉藏语系,为独立语系,中国学者则一般仍将苗瑶语族视为汉藏语系的一个语族。克里斯托弗·贝克威思则不认为汉语族和藏缅语族有发生学关系。

There has been a range of proposals for the Sino-Tibetan urheimat, reflecting the uncertainty about the classification of the family and its time depth.[62] Three major hypotheses for the place and time of Sino-Tibetan unity have been presented:[63]

【参考译文】关于汉藏语系原始家园的所在地,人们提出了各种假设,这反映了人们对该语系分类及其时间深度的不确定性。[62]关于汉藏语系统一的时间和地点,人们提出了三种主要假设:[63]

- 最广为接受的假说是“北方说”,将汉藏语系和黄河流域的新石器文化联系起来,如磁山文化(公元前6500–5000年, 河北省), 仰韶文化(公元前5000–3000年,陕西、甘肃东部、河南西部一带)或马家窑文化(公元前3300–2000年,甘肃中东部、青海东北部一带)[1],伴随小米农业的扩张而扩张。这种情况和汉语族和藏缅语族的分类有关。此说认为所有汉藏语中,汉语是最早分化出去的,其余的语言,即藏缅语族有共同原始语,后来藏缅语人群逐渐向西南方向迁徙并分化,形成了各个语支[13][1]。支持者包括白保罗、马提索夫等[14][15]。

- 复旦大学张梦翰等(2019)进行的对109种汉藏语的计算机系统发生学分析发现,汉藏语系于约公元前2200至5800年(平均公元前3900年)最早分化于中国北方[1][16]:112-115。沙加尔等 (2019)的基于不同数据与方法的计算机系统发生学分析也得出了相近的结论,但汉藏语系分化日期则是约公元前5200年,这可以和晚期磁山文化和早期仰韶文化的小米农民相联系。[17]:10317-10322。

- 詹姆斯·马提索夫认为汉藏语系的最晚分裂发生于约公元前4000年,汉语使用者在黄河沿岸定居,其他族群沿长江、湄公河、萨尔温江和布拉马普特拉河南迁。[18]:470–471此研究同意汉语是最早从汉藏语系中分化出来的,而藏缅语构成一个单独的支系[1]。根据此研究,汉藏语的首次分化时间约在公元前4000年,而藏缅语内部分化约从公元前2800年开始[1]。

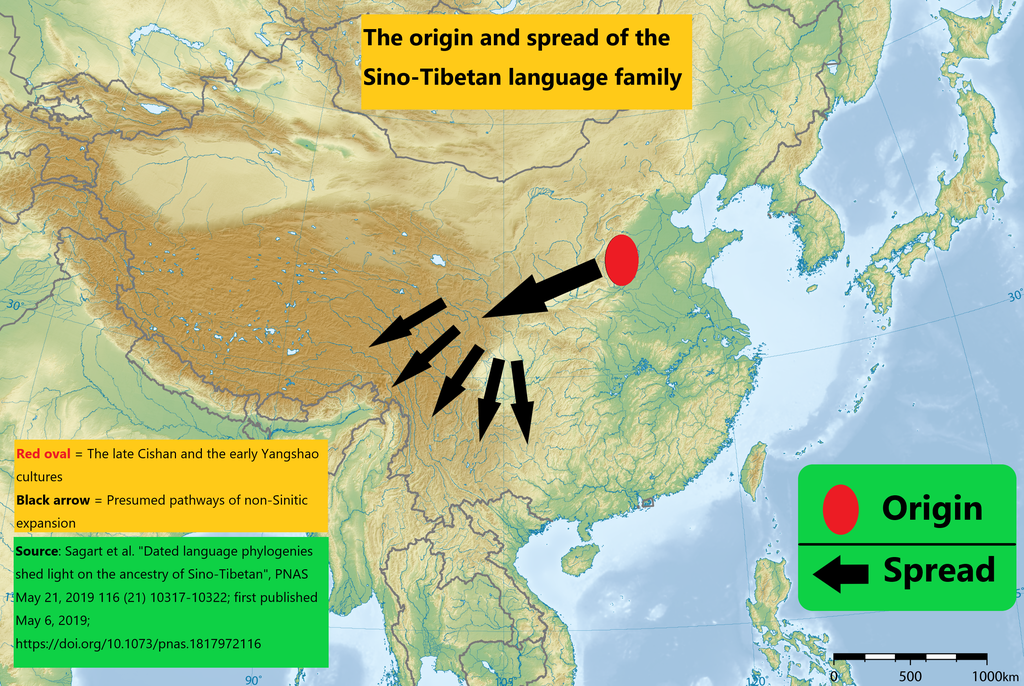

- Sagart et al. (2019) performed another phylogenetic analysis based on different data and methods to arrive at the same conclusions to the homeland and divergence model but proposed an earlier root age of approximately 7,200 years ago, associating its origin with millet farmers of the late Cishan culture and early Yangshao culture.[70]

【参考译文】萨加特等人(2019年)基于不同的数据和方法进行了另一项系统发育分析,得出了关于原始家园和分化模式的相同结论,但提出了一个更早的根源时间,即大约7200年前,将其起源与晚期磁山文化和早期仰韶文化的小米农民联系起来。[70] - Both of these studies have been criticized by Orlandi (2021) for their reliance on lexical items, which are not seen as robust indicators of language ancestry.[71]

【参考译文】奥兰迪(Orlandi,2021年)对这两项研究都提出了批评,因为它们依赖于词汇项目,而这些项目并不被视为语言起源的可靠指标。[71]

图片来源:Ksiom, Abooop

图片题注:Hypothesised homeland and dispersal according to Sagart et al. (2019)[70]

参考译文:根据Sagart等人(2019年)的假设,原始家园与扩散情况[70]

- George van Driem proposes a Sino-Tibetan homeland in the Sichuan Basin before 9000 years BP, with an associated taxonomy reflecting various outward migrations over time, first into northeast India, and later north (the predecessors of Chinese and Tibetic) and south (Karen and Lolo–Burmese).[66]

【参考译文】乔治·范·德里姆(George van Driem)提出,9000年前,汉藏语系的原始家园位于四川盆地,与之相关的分类学反映了随着时间的推移,各种向外迁徙的情况,首先是迁徙到印度东北部,然后是向北(形成汉语和藏语的祖先)和向南(形成克伦语和彝缅语的祖先)迁徙。[66]

图片题注:Hypothesised homeland and dispersal according to van Driem (2005)[72]

图片来源:SUM1

- 罗杰·布伦奇和马克·博斯特(Mark Post)(2014)认为汉藏语系发源于约公元前7000年的印度东北部,那里是语言多样性最大的地方。[19]:89罗杰·布伦奇(2009)认为农业词汇不能构拟进原始汉藏语,汉藏语系最早的使用者不是农民,而是相当多样的渔猎人群。[20][1][13]。此观点认为最早分化的汉藏语言有9000年以上甚至上万年的历史。

图片题注:Hypothesised homeland and dispersal according to Blench (2009)[73][74]

参考译文:根据布伦奇(Blench,2009年)的假设,原始家园与扩散情况[73][74]

图片来源:SUM1

5. 分类 | Classification

Several low-level branches of the family, particularly Lolo-Burmese, have been securely reconstructed, but in the absence of a secure reconstruction of a Sino-Tibetan proto-language, the higher-level structure of the family remains unclear.[75][76] Thus, a conservative classification of Sino-Tibetan/Tibeto-Burman would posit several dozen small coordinate families and isolates; attempts at subgrouping are either geographic conveniences or hypotheses for further research.[citation needed]

【参考译文】几个汉藏语系的低级分支,特别是彝缅语支,已经被可靠地重构,但由于缺乏对汉藏语原始语言的可靠重构,该语系的高级结构仍然不明确。[75][76]因此,对汉藏语系/藏缅语支的一种保守分类会假定存在几十个小的并列语族和孤立语言;对子群的分类要么是出于地理上的便利,要么是为了进一步研究所提出的假设。[需要引证]

5.1 Li (1937)

In a survey in the 1937 Chinese Yearbook, Li Fang-Kuei described the family as consisting of four branches:[77][78]

【参考译文】在1937年的《中国年鉴》的一项调查中,李方桂将汉藏语系描述为由以下四个分支组成:[77][78]

- Indo-Chinese (Sino-Tibetan)【印支语(汉藏语系)】

- Chinese【汉语】

- Tai (later expanded to Kam–Tai)【侗台语(后扩展为侗傣语)】

- Miao–Yao (Hmong–Mien)【苗瑶语】

- Tibeto-Burman【藏缅语】

Tai and Miao–Yao were included because they shared isolating typology, tone systems and some vocabulary with Chinese. At the time, tone was considered so fundamental to language that tonal typology could be used as the basis for classification. In the Western scholarly community, these languages are no longer included in Sino-Tibetan, with the similarities attributed to diffusion across the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, especially since Benedict (1942).[78] The exclusions of Vietnamese by Kuhn and of Tai and Miao–Yao by Benedict were vindicated in 1954 when André-Georges Haudricourt demonstrated that the tones of Vietnamese were reflexes of final consonants from Proto-Mon–Khmer.[79]

【参考译文】之所以将侗台语和苗瑶语包括在内,是因为它们与汉语在孤立型语言类型、声调系统和一些词汇上有所共享。当时,声调被视为语言的基础,因此可以根据声调类型来进行分类。在西方学术界,自本尼迪克特(Benedict,1942年)以来,这些语言已不再被归入汉藏语系,而是将它们之间的相似性归因于东南亚大陆语言区域的扩散。库恩(Kuhn)将越南语排除在外,本尼迪克特将侗台语和苗瑶语排除在外,这一做法在1954年得到了安德烈-乔治·奥德里库尔(André-Georges Haudricourt)的证实,他证明越南语的声调是原始孟-高棉语尾辅音的反映。[79]

Many Chinese linguists continue to follow Li’s classification.[d][78] However, this arrangement remains problematic. For example, there is disagreement over whether to include the entire Kra–Dai family or just Kam–Tai (Zhuang–Dong excludes the Kra languages), because the Chinese cognates that form the basis of the putative relationship are not found in all branches of the family and have not been reconstructed for the family as a whole. In addition, Kam–Tai itself no longer appears to be a valid node within Kra–Dai.

【参考译文】许多中国语言学家仍然遵循李方桂的分类。[d][78]然而,这种分类仍然存在问题。例如,关于是否应将整个侗傣语系或仅侗台语(侗水语排除侗傣语系中的侗-台语支以外的语言)纳入其中存在争议,因为构成假定关系的汉语同源词并非在该语系的所有分支中都能找到,也尚未对整个语系进行重构。此外,侗台语本身在侗傣语系中似乎也不再是一个有效的节点。

【英文词条原注d】See, for example, the “Sino-Tibetan” (汉藏语系 Hàn-Zàng yǔxì) entry in the “languages” (語言文字, Yǔyán-Wénzì) volume of the Encyclopedia of China (1988).

【参考译文】例如,参见《中国大百科全书》(1988年)“语言文字(Yǔyán-Wénzì)”卷中的“汉藏语系(Hàn-Zàng yǔxì)”条目。

5.2 Benedict (1942)

Benedict overtly excluded Vietnamese (placing it in Mon–Khmer) as well as Hmong–Mien and Kra–Dai (placing them in Austro-Tai). He otherwise retained the outlines of Conrady’s Indo-Chinese classification, though putting Karen in an intermediate position:[80][81]

【参考译文】本尼迪克特明确地将越南语(将其归入孟-高棉语系)以及苗瑶语和侗傣语(将其归入澳泰语系)排除在外。除此之外,他基本上保留了康拉德(Conrady)的印支语系分类的轮廓,尽管他将克伦语置于一个中间位置:[80][81]

- Sino-Tibetan【汉藏语系】

- Chinese【汉语】

- Tibeto-Karen【藏-克伦语族】

- Karen【克伦语】

- Tibeto-Burman【藏缅语支】

5.3 Shafer (1955)

Shafer criticized the division of the family into Tibeto-Burman and Sino-Daic branches, which he attributed to the different groups of languages studied by Konow and other scholars in British India on the one hand and by Henri Maspero and other French linguists on the other.[82] He proposed a detailed classification, with six top-level divisions:[83][84][e]

【参考译文】沙弗(Shafer)批评了将汉藏语系分为藏缅语支和汉傣语支(这里“Sino-Daic”可能是一个笔误或特定上下文中的用法,通常我们说的是“Sino-Tibetan”即汉藏语系下的不同分支,而“汉傣语支”并非一个标准的学术分类,可能是指与汉语和侗傣语相关的语言分支,但在此处为保持与原文一致,仍采用“Sino-Daic”这一表述)的做法,他认为这种分类是由于科诺(Konow)和其他英国印度学者与亨利·马斯佩罗(Henri Maspero)和其他法国语言学家所研究的不同语言群体所导致的。[82]沙弗提出了一个详细的分类,其中包含六个顶级分支:[83][84][e]

【英文词条原注e】For Shafer, the suffix “-ic” denoted a primary division of the family, whereas the suffix “-ish” denoted a sub-division of one of those.

【参考译文】对于沙弗来说,后缀“-ic”表示语系的一个主要分支,而后缀“-ish”则表示这些主要分支中的一个次级分支。

- Sino-Tibetan【汉藏语系】

- Sinitic【汉语族】

- Daic【傣语族】

- Bodic【藏语族】

- Burmic【缅语族】

- Baric【波罗-加罗语族】

- Karenic【克伦语族】

Shafer was sceptical of the inclusion of Daic, but after meeting Maspero in Paris decided to retain it pending a definitive resolution of the question.[85][86]

【参考译文】沙弗对将傣语族纳入汉藏语系持怀疑态度,但在巴黎与马斯佩罗会面后,他决定在问题得到最终解决之前保留这一分类。[85][86]

5.4 Matisoff (1978, 2015)

James Matisoff abandoned Benedict’s Tibeto-Karen hypothesis:

【参考译文】James Matisoff 摒弃了 Benedict 的藏缅-克伦(Tibeto-Karen)假说:

- Sino-Tibetan【汉藏语系】

- Chinese【汉语】

- Tibeto-Burman【藏缅语族】

Some more-recent Western scholars, such as Bradley (1997) and La Polla (2003), have retained Matisoff’s two primary branches, though differing in the details of Tibeto-Burman. However, Jacques (2006) notes, “comparative work has never been able to put forth evidence for common innovations to all the Tibeto-Burman languages (the Sino-Tibetan languages to the exclusion of Chinese)”[f] and that “it no longer seems justified to treat Chinese as the first branching of the Sino-Tibetan family,”[g] because the morphological divide between Chinese and Tibeto-Burman has been bridged by recent reconstructions of Old Chinese.

【参考译文】一些较近的西方学者,如 Bradley(1997年)和 La Polla(2003年),保留了 Matisoff 提出的两个主要分支的分类,尽管在藏缅语支的细节上存在差异。然而,Jacques(2006年)指出,“比较研究工作从未能够提出证据证明所有藏缅语(排除汉语后的汉藏语系语言)都有共同的创新之处”[f],并且“将汉语视为汉藏语系中最早分支的处理方式似乎不再合理”[g],因为根据最近对上古汉语的重建,汉语和藏缅语之间的形态学鸿沟已经被弥合。

【英文词条原注f(原文为法文)】les travaux de comparatisme n’ont jamais pu mettre en évidence l’existence d’innovations communes à toutes les langues « tibéto-birmanes » (les langues sino-tibétaines à l’exclusion du chinois)

【参考译文】比较研究从未能够突出所有“藏缅语” (不包括汉语的汉藏语系) 共同的创新的存在

【英文词条原注g(原文为法文)】il ne semble plus justifié de traiter le chinois comme le premier embranchement primaire de la famille sino-tibétaine

【参考译文】把汉语视为汉藏语系的第一个主要分支似乎不再合理

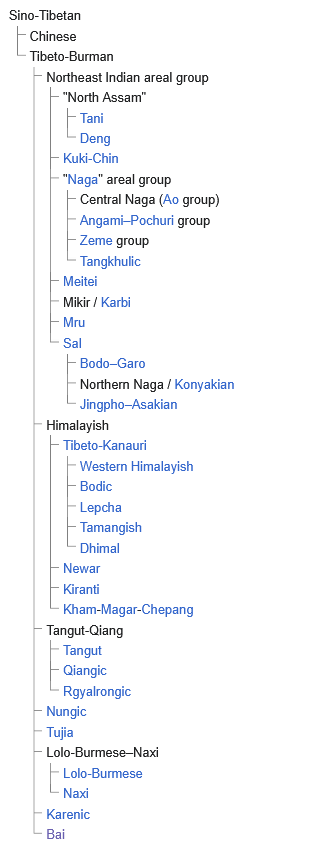

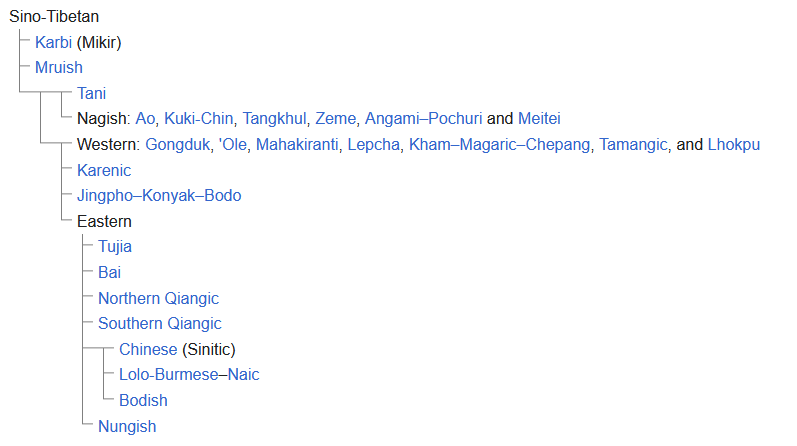

The internal structure of Sino-Tibetan has been tentatively revised as the following Stammbaum by Matisoff in the final print release of the Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus (STEDT) in 2015.[87] Matisoff acknowledges that the position of Chinese within the family remains an open question.[88]

【参考译文】在2015年《汉藏语同源词典》(Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus,STEDT)的最终印刷版中,Matisoff初步将汉藏语系的内部结构修订为如下的系谱树。[87]Matisoff承认,汉语在汉藏语系中的位置仍然是一个悬而未决的问题。[88]

- Sino-Tibetan【汉藏语系】

- Chinese【汉语】

- Tibeto-Burman【藏缅语族】

- Northeast Indian areal group【印度东北部地区语言群】

- “North Assam”【北阿萨姆邦】

- Kuki-Chin【库基钦语(中南藏缅语)】

- “Naga” areal group【那加地区语言群】

- Central Naga (Ao group)【中部那加语(阿奥语群)】

- Angami–Pochuri group【安加米-波楚里语群】

- Zeme group【泽米语群】

- Tangkhulic【唐胡利克语】

- Meitei【梅泰语】

- Mikir / Karbi【卡比语】

- Mru【姆鲁语】

- Sal【萨尔语】

- Bodo–Garo【博罗-加罗语】

- Northern Naga / Konyakian【被那加语/科尼亚克语】

- Jingpho–Asakian【景颇-阿萨基语】

- Himalayish【喜马拉雅地区语言群】

- Tangut-Qiang【西夏-羌语言群】

- Tangut【西夏语】

- Qiangic【羌语】

- Rgyalrongic【嘉绒语】

- Nungic【侬语支】

- Tujia【土家语】

- Lolo-Burmese–Naxi【彝-缅-纳西语言群】

- Lolo-Burmese【缅彝语支】

- Naxi【纳西语】

- Karenic【克伦语】

- Bai【白语】

- Northeast Indian areal group【印度东北部地区语言群】

5.5 Starostin (1996)

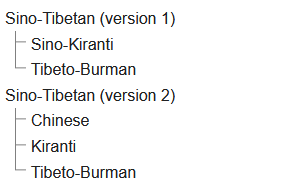

Sergei Starostin proposed that both the Kiranti languages and Chinese are divergent from a “core” Tibeto-Burman of at least Bodish, Lolo-Burmese, Tamangic, Jinghpaw, Kukish, and Karen (other families were not analysed) in a hypothesis called Sino-Kiranti. The proposal takes two forms: that Sinitic and Kiranti are themselves a valid node or that the two are not demonstrably close so that Sino-Tibetan has three primary branches:

【参考译文】谢尔盖·斯塔罗斯金(Sergei Starostin)提出了一个名为“汉-基兰蒂语假说”(Sino-Kiranti)的假设,认为基兰蒂语族和汉语都是从至少包括博迪语、缅彝语、塔芒语族、景颇语、库基语和克伦语(其他语族未分析)的“核心”藏缅语族中分化出来的。这一假设有两种形式:一是认为汉藏语和基兰蒂语本身就是一个有效的节点;二是认为这两者之间并没有明确的亲缘关系,因此藏缅语族有三个主要分支:

- Sino-Tibetan (version 1)【汉藏语系(版本1)】

- Sino-Kiranti【汉-基兰蒂语族】

- Tibeto-Burman【藏缅语族】

- Sino-Tibetan (version 2)【汉藏语系(版本2)】

- Chinese【汉语族】

- Kiranti【基兰蒂语族】

- Tibeto-Burman【藏缅语族】

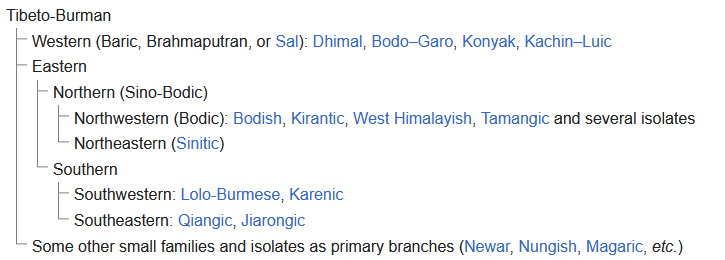

5.6 Van Driem (1997, 2001)

George van Driem, like Shafer, rejects a primary split between Chinese and the rest, suggesting that Chinese owes its traditional privileged place in Sino-Tibetan to historical, typological, and cultural, rather than linguistic, criteria. He calls the entire family “Tibeto-Burman”, a name he says has historical primacy,[89] but other linguists who reject a privileged position for Chinese nevertheless continue to call the resulting family “Sino-Tibetan”.

【参考译文】乔治·范·德里姆(George van Driem)与谢弗(Shafer)持相似观点,他否认汉语与其他藏缅语之间存在主要的分裂,认为汉语在藏缅语系中传统上的特殊地位是基于历史、类型学和文化的标准,而非语言学标准。他将整个语系称为“藏缅语族”(Tibeto-Burman),并表示这一名称在历史上具有优先性,[89]但其他否认汉语享有特殊地位的语言学家仍然将这一语系称为“汉藏语系”。

Like Matisoff, van Driem acknowledges that the relationships of the “Kuki–Naga” languages (Kuki, Mizo, Meitei, etc.), both amongst each other and to the other languages of the family, remain unclear. However, rather than placing them in a geographic grouping, as Matisoff does, van Driem leaves them unclassified. He has proposed several hypotheses, including the reclassification of Chinese to a Sino-Bodic subgroup:

【参考译文】与马提索夫(Matisoff)一样,范·德里姆也承认“库基-那加”(Kuki–Naga)语言(包括库基语、米佐语、梅泰语等)之间的关系以及它们与该语系中其他语言的关系仍不明确。然而,与马提索夫将它们归入地理分组不同,范·德里姆未对它们进行分类。他提出了几个假设,包括将汉语重新归类为汉-博迪(Sino-Bodic)亚组:

- Tibeto-Burman【藏缅语族】

- Western (Baric, Brahmaputran, or Sal): Dhimal, Bodo–Garo, Konyak, Kachin–Luic

【参考译文】西部语支包括:迪马尔语、博多-加罗语、科尼亚克语以及景颇-卢语。 - Eastern【东部语支】

- Northern (Sino-Bodic)

【参考译文】北方(汉-博迪)语支- Northwestern (Bodic): Bodish, Kirantic, West Himalayish, Tamangic and several isolates

【参考译文】西北(博迪)语支:博迪语族、基兰蒂语族、西喜马拉雅语族、塔芒语族以及几种孤立语言 - Northeastern (Sinitic)

【参考译文】东北(汉)语支

- Northwestern (Bodic): Bodish, Kirantic, West Himalayish, Tamangic and several isolates

- Southern【南部语支】

- Southwestern: Lolo-Burmese, Karenic

【参考译文】缅彝语、克伦语 - Southeastern: Qiangic, Jiarongic

【参考译文】东南语支:羌语、嘉绒语

- Southwestern: Lolo-Burmese, Karenic

- Northern (Sino-Bodic)

- Some other small families and isolates as primary branches (Newar, Nungish, Magaric, etc.)

【参考译文】其他一些小的语族和孤立语言作为主要分支(如纽瓦尔语族、侬语支、马加语族等)。

- Western (Baric, Brahmaputran, or Sal): Dhimal, Bodo–Garo, Konyak, Kachin–Luic

Van Driem points to two main pieces of evidence establishing a special relationship between Sinitic and Bodic and thus placing Chinese within the Tibeto-Burman family. First, there are some parallels between the morphology of Old Chinese and the modern Bodic languages. Second, there is a body of lexical cognates between the Chinese and Bodic languages, represented by the Kirantic language Limbu.[90]

【参考译文】范·德里姆提出了两项主要证据,用以证明汉语和博迪语之间存在特殊关系,从而将汉语归入藏缅语族。首先,古代汉语的形态与现代博迪语之间存在一些相似之处。其次,汉语和博迪语之间存在一系列同源词,这以基兰蒂语族的林布语为代表。[90]

In response, Matisoff notes that the existence of shared lexical material only serves to establish an absolute relationship between two language families, not their relative relationship to one another. Although some cognate sets presented by van Driem are confined to Chinese and Bodic, many others are found in Sino-Tibetan languages generally and thus do not serve as evidence for a special relationship between Chinese and Bodic.[91]

【参考译文】针对这一观点,马提索夫指出,共享词汇材料的存在仅用于确定两个语言家族之间的绝对关系,而非它们之间的相对关系。尽管范·德里姆提出的一些同源词仅限于汉语和博迪语,但许多其他同源词在藏缅语系语言中普遍存在,因此不能作为汉语和博迪语之间存在特殊关系的证据。[91]

5.7 范德里姆的“落叶”模型(2001 年、2014 年)| Van Driem’s “fallen leaves” model (2001, 2014)

Van Driem has also proposed a “fallen leaves” model that lists dozens of well-established low-level groups while remaining agnostic about intermediate groupings of these.[92] In the most recent version (van Driem 2014), 42 groups are identified (with individual languages highlighted in italics):[93]

【参考译文】范·德里姆还提出了一个“落叶”模型,该模型列出了数十个已确立的低级群组,同时对这些群组的中间层级保持不可知论的态度。[92] 在最新版本(范·德里姆2014年)中,确定了42个群组(个别语言以斜体突出显示):[93]

- Bodish【博迪语】

- Tshangla【仓格拉语】

- West Himalayish【西喜马拉雅语】

- Tamangic【塔曼吉语】

- Newaric【尼瓦尔语】

- Kiranti【基兰蒂语】

- Lepcha【雷布查语】

- Magaric【马嘉语】

- Chepangic【切潘语】

- Raji–Raute【拉吉-拉乌特语】

- Dura【杜拉语】

- ‘Ole【黑山门巴语】

- Gongduk【贡杜克语】

- Lhokpu【洛普语】

- Siangic【锡安格语】

- Kho-Bwa【科布瓦语】

- Hrusish【赫鲁希语】

- Digarish【迪加罗语】

- Midžuish【米居语】

- Tani【塔尼语】

- Dhimalish【迪马利语】

- Brahmaputran (Sal)【布拉马普特拉语(萨尔语)】

- Pyu【骠语】

- Ao【奥语或中央那加语】

- Angami–Pochuri【安加米-波丘里语】

- Tangkhul【唐库利语】

- Zeme【泽美语】

- Meithei【梅泰语】

- Kukish【库基钦语】

- Karbi【卡尔比语】

- Mru【姆鲁语】

- Sinitic【汉语】

- Bai【白语】

- Tujia【土家语】

- Lolo-Burmese【缅彝语】

- Qiangic【羌语】

- Ersuish【尔苏语】

- Naic【纳西语】

- Rgyalrongic【嘉绒语】

- Kachinic【克钦语(景颇语)】

- Nungish【侬语】

- Karenic【克伦语】

He also suggested (van Driem 2007) that the Sino-Tibetan language family be renamed “Trans-Himalayan”, which he considers to be more neutral.[94]

【参考译文】他还建议(范·德里姆2007年)将汉藏语系更名为“跨喜马拉雅语系”,他认为这个名称更为中立。[94]

Orlandi (2021) also considers the van Driem’s Trans-Himalayan fallen leaves model to be more plausible than the bifurcate classification of Sino-Tibetan being split into Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman.[95]

【参考译文】奥兰迪(2021年)也认为,与将汉藏语系二分为汉语和藏缅语的做法相比,范·德里姆提出的跨喜马拉雅“落叶”模型更为可信。[95]

5.8 Blench and Post (2014)

Roger Blench and Mark W. Post have criticized the applicability of conventional Sino-Tibetan classification schemes to minor languages lacking an extensive written history (unlike Chinese, Tibetic, and Burmese). They find that the evidence for the subclassification or even ST affiliation in all of several minor languages of northeastern India, in particular, is either poor or absent altogether.

【参考译文】罗杰·布伦奇和马克·W·波斯特批评了传统汉藏语系分类方案对于缺乏广泛书面历史记录的小语种(不同于汉语、藏语和缅甸语)的适用性。他们发现,特别是在印度东北部的几种小语种中,关于其亚类划分甚至是否属于汉藏语系的证据要么不足,要么完全缺失。

While relatively little has been known about the languages of this region up to and including the present time, this has not stopped scholars from proposing that these languages either constitute or fall within some other Tibeto-Burman subgroup. However, in the absence of any sort of systematic comparison – whether the data are thought reliable or not – such “subgroupings” are essentially vacuous. The use of pseudo-genetic labels such as “Himalayish” and “Kamarupan” inevitably gives an impression of coherence which is at best misleading.

【参考译文】尽管迄今为止,人们对这一地区的语言了解相对较少,但这并没有阻止学者们提出这些语言要么构成要么属于其他藏缅语亚组的观点。然而,在没有进行任何形式的系统比较的情况下——无论数据是否被认为可靠——这样的“亚组划分”基本上是空洞的。使用诸如“喜马拉雅语”和“卡鲁潘语”等伪遗传标签不可避免地会给人一种连贯性的印象,而这最多只能算是误导。— Blench & Post (2014), p. 3

【参考译文】——布伦奇与波斯特(2014年),第3页

In their view, many such languages would for now be best considered unclassified, or “internal isolates” within the family. They propose a provisional classification of the remaining languages:

【参考译文】在他们看来,目前最好将这些语言中的许多视为未分类的,或是该语系内的“内部孤立语言”。他们为其余语言提出了一个临时分类方案:

- Sino-Tibetan【汉藏语系】

- Karbi (Mikir)【卡比语】

- Mruish【姆鲁语】

- Western: Gongduk, ‘Ole, Mahakiranti, Lepcha, Kham–Magaric–Chepang, Tamangic, and Lhokpu

【西部语群包括贡杜克语、’Ole语、马哈基兰蒂语、雷布查语、坎-马加-切邦语、塔芒语族以及洛克布语】- Karenic【克伦语】

- Jingpho–Konyak–Bodo【景颇-康雅克-博多】

- Eastern【东部语群】

- Tujia【土家语】

- Bai【白语】

- Northern Qiangic【北部羌语】

- Southern Qiangic【南部羌语】

- Chinese (Sinitic)【汉语】

- Lolo-Burmese–Naic【彝-缅-纳西语】

- Bodish【博迪语】

- Nungish【侬语】

Following that, because they propose that the three best-known branches may be much closer related to each other than they are to “minor” Sino-Tibetan languages, Blench and Post argue that “Sino-Tibetan” or “Tibeto-Burman” are inappropriate names for a family whose earliest divergences led to different languages altogether. They support the proposed name “Trans-Himalayan”.

【参考译文】据此,布伦奇和波斯特提出,由于人们普遍认为这三种最著名的语支彼此之间的亲缘关系可能比它们与“小众”汉藏语系的亲缘关系更为紧密,因此他们认为,“汉藏语系”或“藏缅语系”这些名称对于那些最早分化成完全不同的语言的语系来说并不恰当。他们支持使用“跨喜马拉雅语系”这一名称。

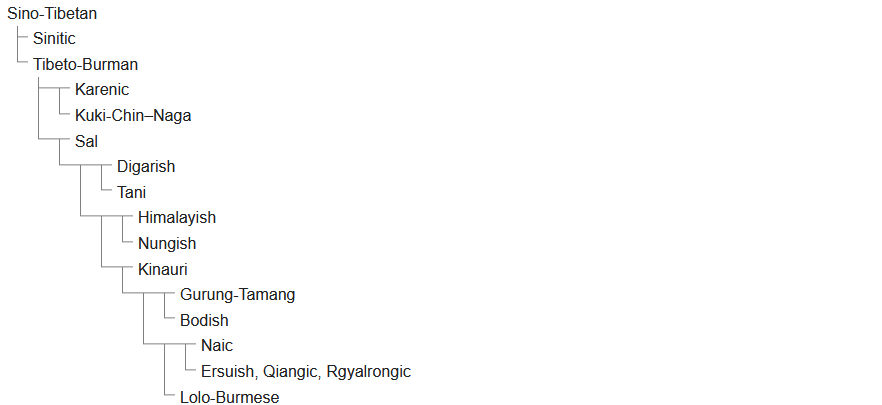

5.9 Menghan Zhang, Shi Yan, et al. (2019)

A team of researchers led by Pan Wuyun and Jin Li proposed the following phylogenetic tree in 2019, based on lexical items:[96]

【参考译文】2019年,潘悟云和金力领导的研究团队基于词汇项目提出了以下语系树:[96]

6. 类型学 | Typology

6.1 语序 | Word order

Except for the Chinese, Bai, Karenic, and Mruic languages, the usual word order in Sino-Tibetan languages is object–verb.[97] However, Chinese and Bai differ from almost all other subject–verb–object languages in the world in placing relative clauses before the nouns they modify.[98] Most scholars believe SOV to be the original order, with Chinese, Karen, and Bai having acquired SVO order due to the influence of neighbouring languages in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area.[99][100] This has been criticized as being insufficiently corroborated by Djamouri et al. 2007, who instead reconstruct a VO order for Proto-Sino-Tibetan.[101]

【参考译文】除汉语、白语、景颇语和克钦语外,汉藏语系中常见的语序是宾语-谓语。[97]然而,汉语和白语与世界上几乎所有其他主谓宾语言不同,它们的定语从句是放在它们所修饰的名词之前的。[98]大多数学者认为主宾谓语序是原始语序,而汉语、景颇语和白语由于受大陆东南亚语言区域邻近语言的影响而采用了主谓宾语序。[99][100]不过,这一观点受到了Djamouri等人2007年研究的批评,他们并未找到足够证据支持这一点,反而认为原始汉藏语是动宾语序。[101]

6.2 音韵学 | Phonology

Contrastive tones are a feature found across the family although absent in some languages like Purik.[102] Phonation contrasts are also present among many, notably in the Lolo-Burmese group.[103] While Benedict contended that Proto-Tibeto-Burman would have a two-tone system, Matisoff refrained from reconstructing it since tones in individual languages may have developed independently through the process of tonogenesis.[104]

【参考译文】对比声调是汉藏语系各语言共有的一个特征,尽管有些语言如普日语并不存在对比声调。[102]许多语言也存在发声对比,特别是缅彝语族的语言。[103]虽然本尼迪克特认为原始藏缅语应该具有双声调系统,但马蒂索夫并没有对其进行重构,因为个别语言中的声调可能是通过声调产生这一过程独立发展而来的。[104]

大部分语言学家认为,原始汉藏语的语音和语法和嘉绒语相似:没有明确的声调系统,有复辅音,有复杂的动词形态。法国学者奥德里库尔早在1954年发现汉语的声调是后起的[35],原始汉语没有声调,到了南北朝韵尾-s和喉塞音分别演变成去声和上声。上古汉语也有保留少量综合性特征,例如:使动的s-前缀:登(端母登韵)上古汉语*təəŋ,增(精母登韵)*s-təəŋ。嘉绒语和藏语里存在着同样的s-使动前缀。

按照历史语言学的定论,声调的有无、语序(动词、主语和宾语的相对位置)、音节结构等类型特征无法支持或者否认语言同源关系的假设,因为这些特征容易扩散到不同的语系。惟有共同的形态成分(前缀、后缀、中缀、元音交替等)和基本词汇才能证明这种关系。

6.3 形态学 | Morphology

6.3.1 单词结构 | The structure of words

Sino-Tibetan is structurally one of the most diverse language families in the world, including all of the gradation of morphological complexity from isolating (Lolo-Burmese, Tujia) to polysynthetic (Gyalrongic, Kiranti) languages.[70] While Sinitic languages are normally taken to be a prototypical example of the isolating morphological type, southern Chinese languages express this trait far more strongly than northern Chinese languages do.[105]

【参考译文】汉藏语系是世界上结构最多样化的语言语系之一,其形态复杂程度从孤立型(如洛洛-缅甸语族、土家语)到多式综合型(如嘉绒语族、基兰蒂语)各不相同。[70]虽然汉语族通常被视为孤立型形态类型的典型代表,但中国南方语言的这一特征远比北方语言强烈。[105]

6.3.2 语态与清浊交替 | Voice and Voicing alternation

Initial consonant alternations related to transitivity are pervasive in Sino-Tibetan; while devoicing (or aspiration) of the initial is associated with a transitive/causative verb, voicing is linked to its intransitive/anticausative counterpart.[106][107] This is argued to reflect morphological derivations that existed in earlier stages of the family. Even in Chinese, one would find semantically-related pairs of verbs such as 見 ‘to see’ (MC: kenH) and 現 ‘to appear’ (ɣenH), which are respectively reconstructed as *[k]ˤen-s and *N-[k]ˤen-s in the Baxter-Sagart system of Old Chinese.[107][108]

【参考译文】在汉藏语系中,与及物性相关的词首辅音交替现象十分普遍;词首辅音的清化(或送气化)通常与及物动词/使役动词相关,而浊化则与非及物动词/反使役动词相对应。[106][107]这被认为反映了该语系早期阶段存在的形态派生现象。即使在汉语中,也能找到语义相关的动词对,如“見”(见,意为“看见”,中古汉语读音为kenH)和“現”(现,意为“出现”,中古汉语读音为ɣenH),在巴克斯特-萨加尔特(Baxter-Sagart)的上古汉语构拟系统中,它们分别被重构为[k]ˤen-s和N-[k]ˤen-s。[107][108]

6.3.3 作格性 | Ergativity

In morphosyntactic alignment, many Tibeto-Burman languages have ergative and/or anti-ergative (an argument that is not an actor) case marking. However, the anti-ergative case markings can not be reconstructed at higher levels in the family and are thought to be innovations.[109]

【参考译文】在形态句法一致性方面,许多藏缅语具有作格和/或非作格(指非施事论元)格标记。然而,非作格格标记不能在更高的语系层级上进行重构,并且被认为是一种创新。[109]

6.3.4 人称指示 | Person indexation

Many Sino-Tibetan languages exhibit a system of person indexation.[110] Notably, Gyalrongic and Kiranti have an inverse marker prefixed to a transitive verb when the agent is lower than the patient in a certain person hierarchy.[111]

【参考译文】许多汉藏语系语言都表现出人称指示系统。[110]值得注意的是,当施事在某种人称层级上低于受事时,嘉绒语族和基兰蒂语会在及物动词前加上一个逆标记前缀。[111]

Hodgson had in 1849 noted a dichotomy between “pronominalized” (inflecting) languages, stretching across the Himalayas from Himachal Pradesh to eastern Nepal, and “non-pronominalized” (isolating) languages. Konow (1909) explained the pronominalized languages as due to a Munda substratum, with the idea that Indo-Chinese languages were essentially isolating as well as tonal. Maspero later attributed the putative substratum to Indo-Aryan. It was not until Benedict that the inflectional systems of these languages were recognized as (partially) native to the family. Scholars disagree over the extent to which the agreement system in the various languages can be reconstructed for the proto-language.[112][113]

【参考译文】1849年,霍奇森(Hodgson)注意到了一种二分法,即“代词化”(屈折)语言和“非代词化”(孤立)语言,这两种语言从喜马拉雅山脉的喜马偕尔邦一直延伸到尼泊尔东部。柯诺(Konow)在1909年解释了代词化语言是由于蒙达语底层的影响,并认为印中语系本质上是孤立的,同时也是有声调的。后来,马斯佩罗(Maspero)将这种假定的底层归因于印欧语系中的印地语支。直到本尼迪克特(Benedict,白保罗)时期,这些语言的屈折系统才被认为是(部分)原生于该语系。学者们对于这些语言中的一致系统能在多大程度上重构为原始语言存在分歧。[112][113]

6.3+1 据实性、惊异性和自我指涉性 | Evidentiality, mirativity, and egophoricity

Although not very common in some families and linguistic areas like Standard Average European, fairly complex systems of evidentiality (grammatical marking of information source) are found in many Tibeto-Burman languages.[114] The family has also contributed to the study of mirativity[115][116] and egophoricity,[117] which are relatively new concepts in linguistic typology.

【参考译文】尽管在一些语系和语言区域(如标准平均欧洲语)中不太常见,但在许多藏缅语中却存在着相当复杂的据实性系统(即信息来源的语法标记)。[114]该语系还对惊异性[115][116]和自我指涉性[117]的研究做出了贡献,这两个概念在语言类型学中相对较新。

7. 被提出的外部关系 | Proposed external relationships

Beyond the traditionally recognized families of Southeast Asia, some possible broader relationships have been suggested.

【参考译文】除了传统上公认的东南亚语系之外,还提出了一些可能存在的更广泛的关系。

7.1 南岛语系 | Austronesian

Main article: Sino-Austronesian languages【主条目:汉-南岛语系】

Laurent Sagart proposes a “Sino-Austronesian” family with Sino-Tibetan and Austronesian (including Kra–Dai as a subbranch) as primary branches. Stanley Starosta has extended this proposal with a further branch called “Yangzian” joining Hmong–Mien and Austroasiatic. The proposal has been largely rejected by other linguists who argue that the similarities between Austronesian and Sino-Tibetan more likely arose from contact rather than being genetic.[126][127][128]

【参考译文】劳伦·萨加特(Laurent Sagart)提出了一个“汉南语系”,其中包括汉藏语系和南岛语系(包括侗台语支作为子分支)作为主要分支。斯坦利·斯塔罗斯塔(Stanley Starosta)进一步扩展了这一提议,加入了一个名为“扬子语系”的分支,将苗瑶语系和南亚语系连接起来。然而,这一提议在很大程度上被其他语言学家所拒绝,他们认为南岛语系和汉藏语系之间的相似性更可能是接触产生的,而非同源关系。[126][127][128]

7.2 德内-叶尼塞语系 | Dené–Yeniseian

Further information: Dené–Yeniseian languages【更多信息:德内-叶尼塞语系】

As noted by Tailleur[129] and Werner,[130] some of the earliest proposals of genetic relations of Yeniseian, by M.A. Castrén (1856), James Byrne (1892), and G.J. Ramstedt (1907), suggested that Yeniseian was a northern relative of the Sino–Tibetan languages. These ideas were followed much later by Kai Donner[131] and Karl Bouda.[132] A 2008 study found further evidence for a possible relation between Yeniseian and Sino–Tibetan, citing several possible cognates.[133] Gao Jingyi (2014) identified twelve Sinitic and Yeniseian shared etymologies that belonged to the basic vocabulary, and argued that these Sino-Yeniseian etymologies could not be loans from either language into the other.[134]

【参考译文】如泰莱尔(Tailleur)[129]和维尔纳(Werner)[130]所指出的,关于叶尼塞语系与汉藏语系之间存在遗传关系的最早的一些提议,是由M.A.卡斯特伦(M.A. Castrén,1856年)、詹姆斯·伯恩(James Byrne,1892年)和G.J.拉姆施泰特(G.J. Ramstedt,1907年)提出的。他们认为叶尼塞语系是汉藏语系的北部亲属语言。这些观点后来被凯·多纳(Kai Donner,131年)和卡尔·布达(Karl Bouda,132年)所继承。2008年的一项研究发现了叶尼塞语系和汉藏语系之间可能存在关系的进一步证据,并引用了几个可能的同源词。[133]高静怡(Gao Jingyi,2014年)确定了12个汉语和叶尼塞语共有的基本词汇词源,并认为这些汉-叶尼塞词源不能是从一种语言借入到另一种语言的。[134]

The “Sino-Caucasian” hypothesis of Sergei Starostin posits that the Yeniseian languages form a clade with Sino-Tibetan, which he called Sino-Yeniseian. The Sino-Caucasian hypothesis has been expanded by others to “Dené–Caucasian” to include the Na-Dené languages of North America, Burushaski, Basque and, occasionally, Etruscan. A narrower binary Dené–Yeniseian family has recently been well received. The validity of the rest of the family, however, is viewed as doubtful or rejected by nearly all historical linguists.[135][136][137] An updated tree by Georgiy Starostin now groups Na-Dene with Sino-Tibetan and Yeniseian with Burushaski (Karasuk hypothesis).[138]

【参考译文】谢尔盖·斯塔罗斯金(Sergei Starostin)提出的“汉高加索语系”假说认为,叶尼塞语系与汉藏语系共同构成了一个支系,他称之为汉-叶尼塞语系。其他人则将汉高加索语系假说扩展为“德内-高加索语系”,以包括北美洲的纳-德内语系、布鲁沙斯基语、巴斯克语,以及偶尔包括伊特鲁里亚语。最近,一个更狭窄的二元德内-叶尼塞语系家族得到了广泛认可。然而,几乎所有历史语言学家都认为该语系家族其余部分的有效性值得怀疑或被拒绝。[135][136][137]格奥尔基·斯塔罗斯金(Georgiy Starostin)提出的一个更新的语系树将纳-德内语系与汉藏语系、叶尼塞语系与布鲁沙斯基语(卡拉苏克假说)进行了分组。[138]

A link between the Na–Dené languages and Sino-Tibetan languages, known as Sino–Dené had also been proposed by Edward Sapir. Around 1920 Sapir became convinced that Na-Dené was more closely related to Sino-Tibetan than to other American families.[139] He wrote a series of letters to Alfred Kroeber where he enthusiastically spoke of a connection between Na-Dene and “Indo-Chinese”. In 1925, a supporting article summarizing his thoughts, albeit not written by him, entitled “The Similarities of Chinese and Indian Languages”, was published in Science Supplements. The Sino-Dene hypothesis never gained foothold in the United States outside of Sapir’s circle, though it was later revitalized by Robert Shafer (1952, 1957, 1969) and Morris Swadesh (1952, 1965).[140] Edward Vadja’s Dené–Yeniseian proposal renewed interest among linguists such as Geoffrey Caveney (2014) to look into support for the Sino–Dené hypothesis. Caveney considered a link between Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené, and Yeniseian to be plausible but did not support the hypothesis that Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dené were related to the Caucasian languages (Sino–Caucasian and Dené–Caucasian).[141]

【参考译文】爱德华·萨丕尔(Edward Sapir)也曾提出纳-德内语系与汉藏语系之间存在联系,即汉-德内语系假说。大约在1920年,萨丕尔确信纳-德内语系与其他美洲语系相比,与汉藏语系的关系更为密切。[139]他给阿尔弗雷德·克罗伯(Alfred Kroeber)写了一系列信件,在信中他热情洋溢地谈论了纳-德内语系与“印支语系”之间的联系。1925年,一篇总结他想法的支持性文章(尽管不是他本人所写),题为《汉语和印度语言的相似性》,发表在《科学补编》上。汉-德内语系假说在萨丕尔圈子之外的美国从未站稳脚跟,尽管后来罗伯特·谢弗(Robert Shafer,1952年、1957年、1969年)和莫里斯·斯瓦德希(Morris Swadesh,1952年、1965年)对其进行了复兴。[140]爱德华·瓦贾(Edward Vadja)提出的德内-叶尼塞语系假说重新激发了语言学家如杰弗里·卡文尼(Geoffrey Caveney,2014年)对汉-德内语系假说的支持兴趣。卡文尼认为汉藏语系、纳-德内语系和叶尼塞语系之间存在联系是合理的,但他并不支持汉藏语系和纳-德内语系与高加索语系(汉高加索语系和德内-高加索语系)有关的假说。[141]

A 2023 analysis by David Bradley using the standard techniques of comparative linguistics supports a distant genetic link between the Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené, and Yeniseian language families. Bradley argues that any similarities Sino-Tibetan shares with other language families of the East Asia area such as Hmong-Mien, Altaic (which is a sprachbund), Austroasiatic, Kra–Dai, Austronesian came through contact; but as there has been no recent contact between the Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené, and Yeniseian language families, any similarities these groups share must be residual.[142]

【参考译文】2023年,大卫·布拉德利(David Bradley)使用比较语言学的标准技术进行分析,支持汉藏语系、纳-德内语系和叶尼塞语系之间存在遥远的遗传联系。布拉德利认为,汉藏语系与东亚地区的其他语系(如苗瑶语系、阿尔泰语系(这是一个语言联盟)、南亚语系、侗台语系、南岛语系)之间的任何相似性都是通过接触产生的;但由于汉藏语系、纳-德内语系和叶尼塞语系之间最近没有接触,因此这些语系之间共享的任何相似性都必须是残留的。[142]

7.3 印欧语系 | Indo-European

Further information: Indo-European languages【更多信息:印欧语系】

August Conrad proposed the Sino-Tibetan-Indo-European language family.[citation needed] This hypothesis holds that there is a genetic relationship between the Sino-Tibetan language family and the Indo-European language family. The earliest comparative linguistic study of Chinese and Indo-European languages was by the 18th-century Nordic scholar Olaus Rudbeck. He compared the vocabulary of Gothic and Chinese and guessed that the two may be of the same origin. In the second half of the 19th century, Kong Haogu, Shigude, Ijosser, etc. successively proposed that Chinese and European languages are homologous. Among them, Kong Haogu, through the comparison of Chinese and Indo-European domestic animal vocabulary, first proposed an Indo-Chinese language macrofamily (including Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese, and Indo-European languages).

【参考译文】奥古斯特·康拉德(August Conrad)曾提出汉藏-印欧语系假说。[需要引证]该假说认为汉藏语系与印欧语系之间存在遗传关系。最早对中国语言和印欧语言进行比较语言学研究的是18世纪的北欧学者奥拉乌斯·鲁德贝克(Olaus Rudbeck)。他比较了哥特语和汉语的词汇,并推测两者可能同源。19世纪后半叶,孔好古、施古德、约瑟夫等人相继提出汉语和欧洲语言同源的观点。其中,孔好古通过比较汉语和印欧语的家畜词汇,首次提出了印中语大语系(包括汉语、藏语、缅甸语和印欧语)。

In the 20th century, R. Shafer put forward the conjecture of a Eurasial language super-family and listed hundreds of similar words between Tibeto-Burman and Indo-European languages.[143][144]

【参考译文】20世纪,R.谢弗(R. Shafer)提出了欧亚语系超家族的猜想,并列出了藏缅语与印欧语之间数百个相似的词汇。[143][144]

参见、参考文献、外部链接

请点击这里访问(辽观海外网站)

分享到: