中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。

关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及根据名称精确检索已搬运的词条,请点击这里访问辽观网站。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

0. 概述

辽观注:此标题是我们在搬运、整合过程中添加的。

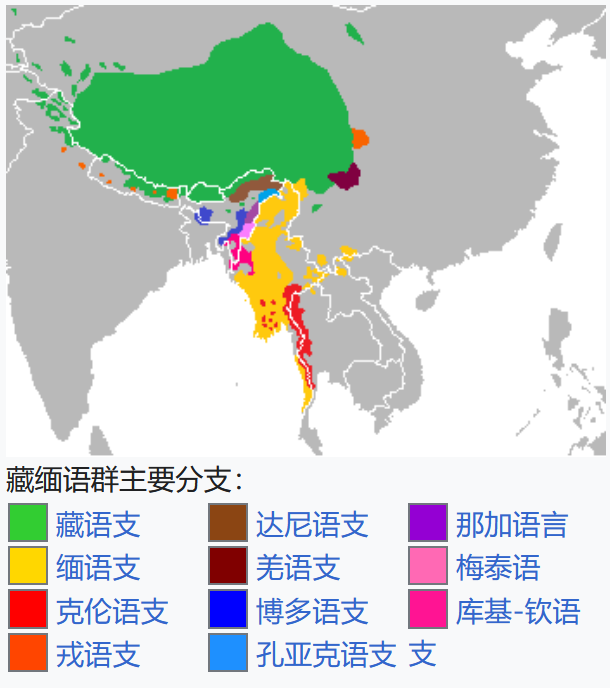

The Tibeto-Burman languages are the non-Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family, over 400 of which are spoken throughout the Southeast Asian Massif (“Zomia”) as well as parts of East Asia and South Asia. Around 60 million people speak Tibeto-Burman languages.[1] The name derives from the most widely spoken of these languages, Burmese and the Tibetic languages, which also have extensive literary traditions, dating from the 12th and 7th centuries respectively. Most of the other languages are spoken by much smaller communities, and many of them have not been described in detail.

【参考译文】藏缅语系是汉藏语系中的非汉语系成员,在东南亚高地(“佐米亚”)以及东亚和南亚的部分地区,有400多种藏缅语被使用。大约6000万人讲藏缅语系语言。[1]该语系名称源自其中使用最广泛的语言——缅甸语和藏语,这两种语言还拥有历史悠久的文学传统,分别可追溯至12世纪和7世纪。大多数其他藏缅语系语言的使用群体要小得多,其中许多语言尚未得到详细描述。

藏缅语族是分布于藏区、中国西南部、印度东北部、尼泊尔、巴基斯坦、不丹、缅甸、泰国、越南等地的一组语言。根据民族语网站2009年的资料,藏缅语族共包含有435种语言[1],其中主要的语言有缅甸语、藏语、彝语、曼尼普尔语等。 藏缅语族语言的总使用人口约有6000万,而缅甸语是藏缅语族中使用人口最多的一种语言,大概有3200万人使用。此外,有700万左右的藏人使用藏语。

藏缅语族不但分布广,而且语种多、差别大,这意味着藏缅语族源远流长,其历史纵深可能足与印欧语系等量齐观。藏缅语族之下到底有多少分支,由于现行分类体系不完整,对现代语言的调查又不够全面,目前尚无定论。如果采取比较保守的分类,加上系属不明之“孤立语言”,如土家语、苏龙语、格曼语、贡都语、达迈语、舍尔都克奔语等,未来承认之独立语支可能将超过二十余个[2]。

藏缅语族的语言多半都没有文字,有较长期文献资料者仅有藏语、缅甸语、西夏语、绒巴语以及彝语五种。其中藏语从7世纪起就有以印度系统字母书写的藏文,为整个汉藏语系中最古老、最精确的标音文献记录,对了解汉藏语系至为关键[2]。

Though the division of Sino-Tibetan into Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman branches (e.g. Benedict, Matisoff) is widely used, some historical linguists criticize this classification, as the non-Sinitic Sino-Tibetan languages lack any shared innovations in phonology or morphology[2] to show that they comprise a clade of the phylogenetic tree.[3][4][5]

【参考译文】尽管将汉藏语系分为汉语和藏缅语两大分支(如本尼迪克特、马提索夫等人的分类)的做法被广泛采用,但一些历史语言学家对这一分类提出批评,因为非汉语的汉藏语系语言在音系或形态学上缺乏任何共享的创新特征[2],无法证明它们构成谱系树中的一个支系。[3][4][5]

图片来源:Fobos92

1. 藏缅语族概念简史 | History

者从“藏文”(起源于7世纪)和“缅文”(起源于12世纪)的相关资料中,发现到这两种语言似乎有某种程度的关联性。在这之后,有一些英国学者以及英国派驻在印度和缅甸的殖民地官员,也开始采用比较有系统的方式,试着对该地区比较不为人知的一些“部落语言进行实地的田野调查和纪录,而发现到这些语言和藏语以及缅语这两个具有文字传统的语言,似乎也有某种程度的亲和关系。在这些相关研究中,George Abraham Grierson的《印度语言调查(Linguistic Survey of India)》(1903-1928,其中有三卷和藏缅语系的语言有关),是这个阶段对于藏缅语言最重要的研究成果(STEDT[4])。

During the 18th century, several scholars noticed parallels between Tibetan and Burmese, both languages with extensive literary traditions. In the following century, Brian Houghton Hodgson collected a wealth of data on the non-literary languages of the Himalayas and northeast India, noting that many of these were related to Tibetan and Burmese.[7] Others identified related languages in the highlands of Southeast Asia and south-west China. The name “Tibeto-Burman” was first applied to this group in 1856 by James Logan, who added Karen in 1858.[8][9] Charles Forbes viewed the family as uniting the Gangetic and Lohitic branches of Max Müller‘s Turanian, a huge family consisting of all the Eurasian languages except the Semitic, “Aryan” (Indo-European) and Chinese languages.[10] The third volume of the Linguistic Survey of India was devoted to the Tibeto-Burman languages of British India.

【参考译文】18世纪时,一些学者注意到藏语和缅甸语之间存在相似之处,这两种语言都有着悠久的文学传统。在接下来的一个世纪里,布莱恩·霍顿·霍奇森收集了大量关于喜马拉雅山脉和印度东北部非文学语言的数据,并指出其中许多语言与藏语和缅甸语有关。[7]其他人也在东南亚高地和中国西南部发现了与这些语言相关的语言。“藏缅语系”这一名称首次由詹姆斯·洛根于1856年应用于这一语群,他于1858年又加入了克伦语。[8][9]查尔斯·福布斯认为,这一语系将马克斯·缪勒的突厥语系中的恒河语支和卢希特语支统一了起来,突厥语系是一个庞大的语系,包括除闪语、“雅利安语”(印欧语系)和汉语以外的所有欧亚语言。[10]《印度语言调查》的第三卷专门探讨了英属印度的藏缅语系语言。

Julius Klaproth had noted in 1823 that Burmese, Tibetan and Chinese all shared common basic vocabulary, but that Thai, Mon and Vietnamese were quite different.[11] Several authors, including Ernst Kuhn in 1883 and August Conrady in 1896, described an “Indo-Chinese” family consisting of two branches, Tibeto-Burman and Chinese-Siamese.[12] The Tai languages were included on the basis of vocabulary and typological features shared with Chinese. Jean Przyluski introduced the term sino-tibétain (Sino-Tibetan) as the title of his chapter on the group in Antoine Meillet and Marcel Cohen‘s Les Langues du Monde in 1924.[13]

【参考译文】1823年,尤利乌斯·克拉普罗特指出,缅甸语、藏语和汉语都有共同的基本词汇,但泰语、孟语和越南语则截然不同。[11]包括恩斯特·库恩(1883年)和奥古斯特·康拉德(1896年)在内的几位作者描述了一个由藏缅语支和汉暹语支组成的“印中语系”。[12]泰语之所以被归入这一语系,是因为它与汉语有共同的词汇和类型学特征。1924年,让·普日卢斯基在安托万·梅耶和马塞尔·科恩的《世界语言》一书中,用“中-藏语系”(汉藏语系)这一术语作为他关于该语系的章节标题。[13]

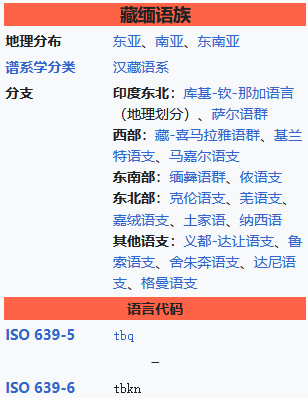

图片题注:汉藏语系的起源与传播。红椭圆是磁山晚期和仰韶早期的文化。黑色箭头是非汉语族的假定途径。在将语言比较方法应用于沙加尔于2019年开发的比较语言数据数据库以识别声音对应关系并建立同源词后,系统发育方法被用于推断这些语言之间的关系并估计其起源和家乡的年龄。[3]

图片来源:Ksiom, Abooop

接下来,虽然有人试着要在藏语和汉语之间找寻其中的亲缘关系,但是,由于相关实证资料的不足,学者并无法对原始藏缅语进行拟构的工作,也因此无法产生什么明确的结论。1930年左右,美国语言学者Robert Shafer在白保罗的协助下,以在该地区工作的殖民地官员和传教士所编写的一些字典和语言研究为基础,首次对后来被归类为藏缅语族的这些语言进行比较有系统的研究工作,也初步将这些语言的系谱关系作了一定程度的厘清。这次研究的成果,是被称之为《汉藏语言学(Sino-Tibetan Linguistics)》(1939-1941)的三卷未出版手稿(STEDT[4])。

The Tai languages have not been included in most Western accounts of Sino-Tibetan since the Second World War, though many Chinese linguists still include them. The link between Tibeto-Burman and Chinese is now accepted by most linguists, with a few exceptions such as Roy Andrew Miller and Christopher Beckwith.[14][15][16] More recent controversy has centred on the proposed primary branching of Sino-Tibetan into Chinese and Tibeto-Burman subgroups. In spite of the popularity of this classification, first proposed by Kuhn and Conrady, and also promoted by Paul Benedict (1972) and later James Matisoff, Tibeto-Burman has not been demonstrated to be a valid subgroup in its own right.[3]

【参考译文】自第二次世界大战以来,泰语在大多数西方关于汉藏语系的论述中并未被纳入,尽管许多中国语言学家仍然将其包括在内。现在,大多数语言学家(罗伊·安德鲁·米勒和克里斯托弗·贝克威思等少数例外)都接受了藏缅语系与汉语之间的联系。[14][15][16]最近的争议主要集中在汉藏语系被划分为汉语和藏缅语两大子组的拟议上。尽管这一分类最初由库恩和康拉德提出,后来也得到了保罗·本尼迪克特(1972年)和詹姆斯·马提索夫的推广,并广受欢迎,但藏缅语本身是否构成一个有效的子组尚未得到证实。[3]

1966年,Shafer第一次正式将他的研究心得加以出版,这就是《汉藏语言介绍(Introduction to Sino-Tibetan)》(见Shafer 1966)这本书。在这本书中,他不但将泰语列入汉藏语系当中,同时也对藏缅语族的各种语言,作了相当详尽的分类。虽然这个分类系统乍看之下十分地合理,但是,由于某些语言的原始资料并不齐备,他的某些分类其实是很有问题的(STEDT[4])。

同样以这些资料为基础,白保罗却获得了和Shafer不太相同的结论。在其1972年所出版的《汉藏语概论(Sino-Tibetan: A Conspectus)》中(这本书的初稿完成于1941年左右),白保罗一方面将泰语排除在汉藏语系之外,另一方面,他则将缅甸北部的克钦语视为是其他藏缅语族语言的“辐射中心”,而将克伦语排除在这个中心之外。虽然白保罗的这本书还留下不少无法解决的难题,但是,目前多数的语言学者都认为,《汉藏语概论》的出版代表了汉藏语系研究的一个新纪元,也在某种程度上对藏缅语族的分类,提供了比较可信的假设(STEDT[4])。

2. 语族概述 | Overview

Most of the Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken in remote mountain areas, which has hampered their study. Many lack a written standard. It is generally easier to identify a language as Tibeto-Burman than to determine its precise relationship with other languages of the group.[17] The subgroupings that have been established with certainty number several dozen, ranging from well-studied groups of dozens of languages with millions of speakers to several isolates, some only discovered in the 21st century but in danger of extinction.[18] These subgroups are here surveyed on a geographical basis.

【参考译文】藏缅语系的大部分语言都在偏远的山区使用,这阻碍了对其的研究。许多藏缅语系语言没有书面的标准形式。通常,确定一种语言属于藏缅语系比确定它与该语系中其他语言的精确关系要容易得多。[17]已确定存在的子组有几十个,范围从拥有数百万使用者的、经过充分研究的几十种语言的群体,到几种孤立语言,其中一些是在21世纪才发现的,但面临灭绝的危险。[18]以下将基于地理位置对这些子组进行概述。

2.1 东南亚与中国西南部 | Southeast Asia and southwest China

The southernmost group is the Karen languages, spoken by three million people on both sides of the Burma–Thailand border. They differ from all other Tibeto-Burman languages (except Bai) in having a subject–verb–object word order, attributed to contact with Tai–Kadai and Austroasiatic languages.[19]

【参考译文】最南端的群体是克伦语群体,该语言在缅甸与泰国边境两侧有三百万人使用。克伦语采用主谓宾词序,这与所有其他藏缅语系语言(白语除外)都不同,这被认为是由于受到了台-卡岱语系和南岛语系语言的影响。[19]

The most widely spoken Tibeto-Burman language is Burmese, the national language of Myanmar, with over 32 million speakers and a literary tradition dating from the early 12th century. It is one of the Lolo-Burmese languages, an intensively studied and well-defined group comprising approximately 100 languages spoken in Myanmar and the highlands of Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and southwest China. Major languages include the Loloish languages, with two million speakers in western Sichuan and northern Yunnan, the Akha language and Hani languages, with two million speakers in southern Yunnan, eastern Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam, and Lisu and Lahu in Yunnan, northern Myanmar and northern Thailand. All languages of the Loloish subgroup show significant Austroasiatic influence.[20] The Pai-lang songs, transcribed in Chinese characters in the 1st century, appear to record words from a Lolo-Burmese language, but arranged in Chinese order.[21]

【参考译文】藏缅语系中使用最广泛的语言是缅甸语,它是缅甸的国语,有三千二百多万使用者,其文学传统可追溯到12世纪初。缅甸语属于缅彝语支,该语支是一个经过深入研究且界定明确的群体,包括缅甸和泰国高地、老挝、越南以及中国西南部使用的约100种语言。主要语言包括在四川西部和云南北部有两百万使用者的洛洛语、在云南南部、缅甸东部、老挝和越南有两百万使用者的阿卡语和哈尼语,以及在云南、缅甸北部和泰国北部使用的傈僳语和拉祜语。洛洛语支的所有语言都受到了南岛语系语言的显著影响。[20]公元1世纪用汉字记录的排郎歌似乎是用洛洛-缅甸语记录的词语,但按照汉语的语序排列。[21]

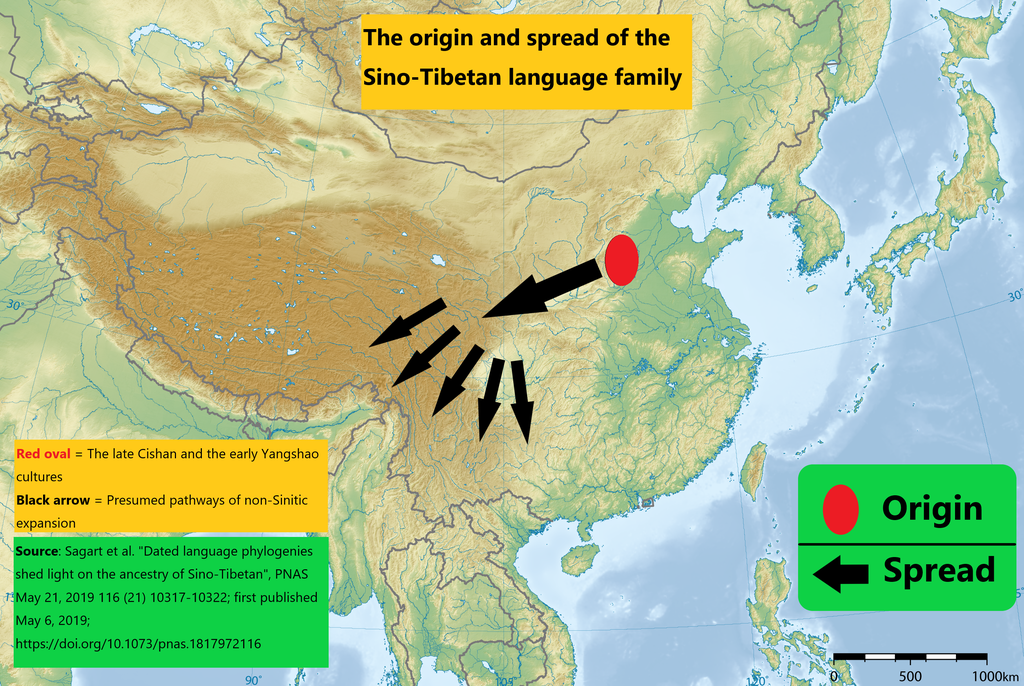

图片题注:Language families of China, with Tibeto-Burman in orange[a]

参考译文:中国的语系,其中藏缅语系以橙色标记[a]

图片来源:Ethnolinguistic_map_of_China_1983.jpg: U.S. Central Intelligence Agency derivative work: Beao – Ethnolinguistic_map_of_China_1983.jpg

【英文词条原注a】Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1983. The map shows the distribution of ethnolinguistic groups according to the historical majority ethnic groups by region. Note this is different from the current distribution due to ongoing internal migration and assimilation.

【参考译文】来源:美国中央情报局,1983年。该地图显示了根据各地区历史上占主导地位的民族划分的民族语言群体的分布。请注意,由于持续的内部迁移和同化,这与当前的分布有所不同。

The Tibeto-Burman languages of south-west China have been heavily influenced by Chinese over a long period, leaving their affiliations difficult to determine. The grouping of the Bai language, with one million speakers in Yunnan, is particularly controversial, with some workers suggesting that it is a sister language to Chinese. The Naxi language of northern Yunnan is usually included in Lolo-Burmese, though other scholars prefer to leave it unclassified.[22] The hills of northwestern Sichuan are home to the small Qiangic and Rgyalrongic groups of languages, which preserve many archaic features. The most easterly Tibeto-Burman language is Tujia, spoken in the Wuling Mountains on the borders of Hunan, Hubei, Guizhou and Chongqing.

【参考译文】中国西南部的藏缅语系语言长期以来深受汉语的影响,这使得它们的归属难以确定。拥有一百万使用者的白语归属颇具争议,一些学者认为白语是汉语的姊妹语言。云南北部的纳西语通常被归入洛洛-缅甸语支,尽管其他学者更倾向于不将其分类。[22]四川西北部的丘陵地带是羌语支和嘉绒语支等小众语言的发源地,这些语言保留了许多古老的特征。最东部的藏缅语系语言是土家语,它在湖南、湖北、贵州和重庆交界的武陵山区使用。

Two historical languages are believed to be Tibeto-Burman, but their precise affiliation is uncertain. The Pyu language of central Myanmar in the first centuries is known from inscriptions using a variant of the Gupta script. The Tangut language of the 12th century Western Xia of northern China is preserved in numerous texts written in the Chinese-inspired Tangut script.[23]

【参考译文】有两种历史语言被认为属于藏缅语族,但它们的确切归属尚不确定。公元初几个世纪缅甸中部的骠语见于使用古普塔文变体的铭文。中国北部西夏王朝12世纪的党项语保存在众多用受汉语启发的西夏文撰写的文献中。[23]

2.2 西藏和南亚 | Tibet and South Asia

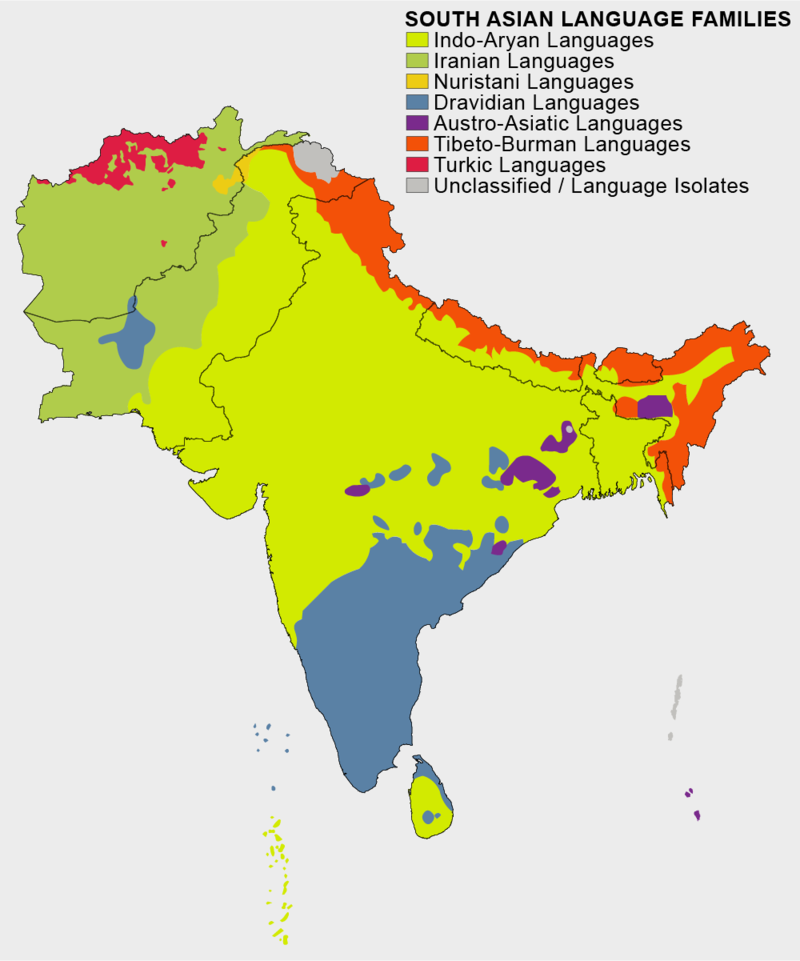

图片题注:Language families of South Asia, with Tibeto-Burman in orange

参考译文:南亚的语系(藏缅语系以橙色标记)

图片来源:Afrogindahood

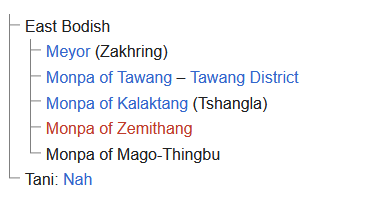

Over eight million people in the Tibetan Plateau and neighbouring areas in Baltistan, Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan speak one of several related Tibetic languages. There is an extensive literature in Classical Tibetan dating from the 8th century. The Tibetic languages are usually grouped with the smaller East Bodish languages of Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh as the Bodish group.

【参考译文】在青藏高原以及邻近的巴尔蒂斯坦、拉达克、尼泊尔、锡金和不丹地区,有八百多万人口使用几种相关的藏语支语言中的一种。古典藏语有着自8世纪以来的丰富文献。藏语支语言通常与不丹和阿鲁纳恰尔邦(印占藏南)的较小东博多语支一起被归为博多语族。

Many diverse Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken on the southern slopes of the Himalayas. Sizable groups that have been identified are the West Himalayish languages of Himachal Pradesh and western Nepal, the Tamangic languages of western Nepal, including Tamang with one million speakers, and the Kiranti languages of eastern Nepal. The remaining groups are small, with several isolates. The Newar language (Nepal Bhasa) of central Nepal has a million speakers and literature dating from the 12th century, and nearly a million people speak Magaric languages, but the rest have small speech communities. Other isolates and small groups in Nepal are Dura, Raji–Raute, Chepangic and Dhimalish. Lepcha is spoken in an area from eastern Nepal to western Bhutan.[24] Most of the languages of Bhutan are Bodish, but it also has three small isolates, ‘Ole (“Black Mountain Monpa”), Lhokpu and Gongduk and a larger community of speakers of Tshangla.[18]

【参考译文】喜马拉雅山脉南坡的人们说着许多不同的藏缅语系语言。已经确定的大规模语言群体包括喜马偕尔邦和尼泊尔西部的西喜马拉雅语、尼泊尔西部包括有一百万使用者的塔芒语在内的塔芒语支,以及尼泊尔东部的基兰蒂语。其余群体规模较小,且存在多种孤立语言。尼泊尔中部的尼瓦尔语(尼泊尔语)有一百万使用者,其文学可追溯至12世纪,而近一百万人说着马加里语,但其余语言的使用群体规模较小。尼泊尔的其他孤立语言和小群体语言包括杜拉语、拉吉-劳特语、切庞语支和迪马利什语。雷布查语的使用范围从尼泊尔东部延伸到不丹西部。[24]不丹的大部分语言属于博多语族,但也有三种小规模的孤立语言,即“黑山蒙巴”语(Ole)、洛克普语(Lhokpu)和龚杜克语(Gongduk),以及一个规模较大的藏拉语使用群体。[18]

The Tani languages include most of the Tibeto-Burman languages of Arunachal Pradesh and adjacent areas of Tibet.[25] The remaining languages of Arunachal Pradesh are much more diverse, belonging to the small Siangic, Kho-Bwa (or Kamengic), Hruso, Miju and Digaro languages (or Mishmic) groups.[26] These groups have relatively little Tibeto-Burman vocabulary, and Bench and Post dispute their inclusion in Sino-Tibetan.[27]

【参考译文】塔尼语包括阿鲁纳恰尔邦(印占藏南)及其邻近西藏地区的大部分藏缅语系语言。[25]阿鲁纳恰尔邦的其余语言则更加多样,分别属于小型的西昂语支、科-布瓦语支(或卡门语支)、赫鲁索语支、米朱语支和迪加罗语支(或米什米语支)等语群。[26]这些语群的藏缅语系词汇相对较少,本奇和波斯特对他们的汉藏语系归属存有争议。[27]

The greatest variety of languages and subgroups is found in the highlands stretching from northern Myanmar to northeast India.

【参考译文】从缅甸北部延伸至印度东北部的高地拥有最为丰富的语言和亚语言种类。

Northern Myanmar is home to the small Nungish group, as well as the Jingpho–Luish languages, including Jingpho with nearly a million speakers. The Brahmaputran or Sal languages include at least the Boro–Garo and Konyak languages, spoken in an area stretching from northern Myanmar through the Indian states of Nagaland, Meghalaya, and Tripura, and are often considered to include the Jingpho–Luish group.[28][29]

【参考译文】缅甸北部是小农吉语支以及景颇-鲁支语言的发源地,其中景颇语有近一百万使用者。布拉马普特拉河语或萨尔语至少包括在从缅甸北部穿过印度那加兰邦、梅加拉亚邦和特里普拉邦的地区使用的博若-加罗语和科尼亚克语,且通常被认为还包括景颇-鲁支语群。[28][29]

The border highlands of Nagaland, Manipur and western Myanmar are home to the small Ao, Angami–Pochuri, Tangkhulic, and Zeme groups of languages, as well as the Karbi language. Meithei, the main language of Manipur with 1.4 million speakers, is sometimes linked with the 50 or so Kuki-Chin languages are spoken in Mizoram and the Chin State of Myanmar.

【参考译文】那加兰邦、曼尼普尔邦和缅甸西部边境的高地是小阿奥语、安加米-波丘里语、唐胡利克语和泽米语等小型语群的发源地,也是卡尔比语的发源地。曼尼普尔邦的主要语言梅泰语有一百四十万使用者,有时与在米佐拉姆邦和缅甸掸邦使用的约五十种库基-钦语联系在一起。

The Mru language is spoken by a small group in the Chittagong Hill Tracts between Bangladesh and Myanmar.[30][31]

【参考译文】在孟加拉国和缅甸之间的吉大港山区,有一小部分人说着姆鲁语。[30][31]

3. 分类 | Classification

There have been two milestones in the classification of Sino-Tibetan and Tibeto-Burman languages, Shafer (1955) and Benedict (1972), which were actually produced in the 1930s and 1940s respectively.

【参考译文】汉藏语系和藏缅语系的分类中有两个里程碑式的研究,分别是沙弗(Shafer)于1955年发表的研究和本尼迪克特(Benedict)于1972年发表的研究,但实际上它们分别是在20世纪30年代和40年代完成的。

3.1 Shafer (1955)

Shafer’s tentative classification took an agnostic position and did not recognize Tibeto-Burman, but placed Chinese (Sinitic) on the same level as the other branches of a Sino-Tibetan family.[32] He retained Tai–Kadai (Daic) within the family, allegedly at the insistence of colleagues, despite his personal belief that they were not related.

【参考译文】沙弗(Shafer)的初步分类持不可知论立场,并未承认藏缅语系的存在,而是将汉语(汉藏语系)与其他汉藏语系分支置于同一层级。[32]尽管他个人认为台语-卡岱语(侗台语)与汉藏语系并无关联,但据称是在同事的坚持下,他仍将台语-卡岱语保留在汉藏语系之内。

3.2 Benedict (1972)

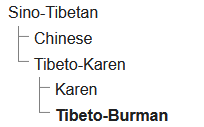

A very influential, although also tentative, classification is that of Benedict (1972), which was actually written around 1941. Like Shafer’s work, this drew on the data assembled by the Sino-Tibetan Philology Project, which was directed by Shafer and Benedict in turn. Benedict envisaged Chinese as the first family to branch off, followed by Karen.

【参考译文】本尼迪克特(Benedict)1972年的分类(实际写于1941年左右)虽然同样具有试探性,但却极具影响力。与沙弗的研究一样,该研究也借鉴了沙弗和本尼迪克特轮流负责的汉藏语言学项目所收集的数据。本尼迪克特设想汉语是最早分化出来的语族,其次是克伦语。

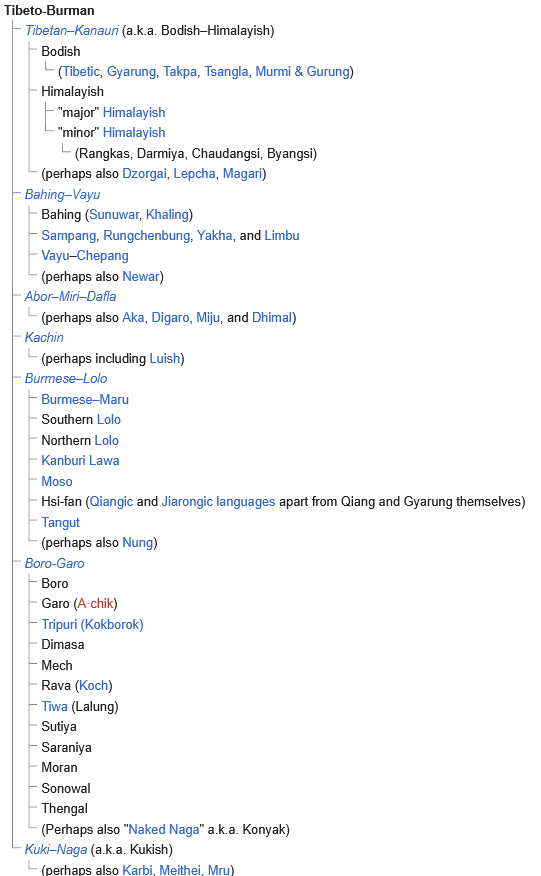

The Tibeto-Burman family is then divided into seven primary branches:

【参考译文】藏缅语系随后被分为七个主要分支:

3.3 Matisoff (1978)

James Matisoff proposes a modification of Benedict that demoted Karen but kept the divergent position of Sinitic.[33] Of the 7 branches within Tibeto-Burman, 2 branches (Baic and Karenic) have SVO-order languages, whereas all the other 5 branches have SOV-order languages.

【参考译文】詹姆斯·马提索夫(James Matisoff)对本尼迪克特的分类进行了修改,降低了克伦语的地位,但保留了汉语的特殊地位。[33]在藏缅语系的七个分支中,有两个分支(白语支和克伦语支)的语言是主谓宾结构(SVO),而其他五个分支的语言都是主宾谓结构(SOV)。

Tibeto-Burman is then divided into several branches, some of them geographic conveniences rather than linguistic proposals:

【参考译文】藏缅语系随后被分为几个分支,其中一些分支是出于地理上的便利而非语言学的建议:

Matisoff makes no claim that the families in the Kamarupan or Himalayish branches have a special relationship to one another other than a geographic one. They are intended rather as categories of convenience pending more detailed comparative work.

【参考译文】马提索夫并没有声称卡马鲁潘语支或喜马拉雅语支中的语族之间存在除地理关系之外的特殊关系。它们更多地是出于便利而设立的类别,有待更详细的比较工作来确定。

Matisoff also notes that Jingpho–Nungish–Luish is central to the family in that it contains features of many of the other branches, and is also located around the center of the Tibeto-Burman-speaking area.

【参考译文】马提索夫还指出,景颇-农吉-鲁支语在藏缅语系中处于核心地位,因为它包含了其他许多语支的特征,并且也位于藏缅语使用地区的中心附近。

3.4 Bradley (2002)

Since Benedict (1972), many languages previously inadequately documented have received more attention with the publication of new grammars, dictionaries, and wordlists. This new research has greatly benefited comparative work, and Bradley (2002) incorporates much of the newer data.[34]

【参考译文】自本尼迪克特(1972年)以来,随着新的语法、词典和词汇表的出版,许多以前记录不充分的语言受到了更多关注。这项新的研究极大地促进了比较语言学的工作,而布拉德利(2002年)的研究中融入了许多更新的数据。[34]

3.5 van Driem

George van Driem rejects the primary split of Sinitic, making Tibeto-Burman synonymous with Sino-Tibetan.

【参考译文】乔治·范·德里姆(George van Driem)不接受汉语作为首要分支的划分,他认为藏缅语系与汉藏语系是同义词。

3.6 Matisoff (2015)

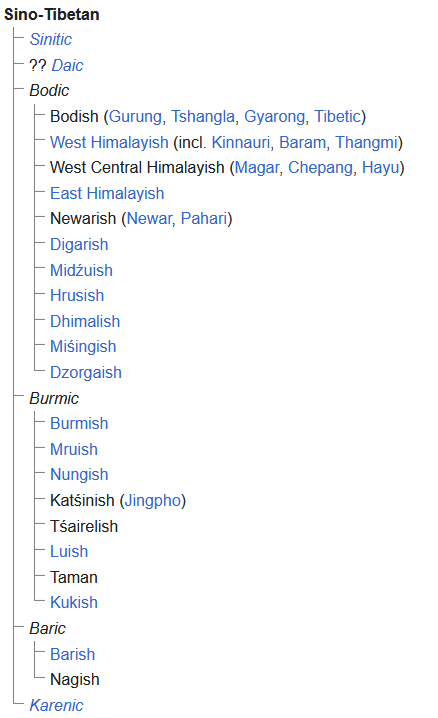

The internal structure of Tibeto-Burman is tentatively classified as follows by Matisoff (2015: xxxii, 1123–1127) in the final release of the Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus (STEDT).[35][36]

【参考译文】在马提索夫(Matisoff)于《汉藏语同源词典与词库》(STEDT)最终版(2015:xxxii,1123–1127)中,藏缅语系的内部结构被初步分类如下。[35][36]

3.7 其他语言 | Other languages

The classification of Tujia is difficult due to extensive borrowing. Other unclassified Tibeto-Burman languages include Basum and the Songlin and Chamdo languages, both of which were only described in the 2010s. New Tibeto-Burman languages continue to be recognized, some not closely related to other languages. Distinct languages only recognized in the 2010s include Koki Naga.

【参考译文】由于土家语的广泛借用,其分类变得困难。其他未被分类的藏缅语包括巴苏姆语以及松林语和昌都语,这两种语言都只在2010年代被描述。不断有新的藏缅语被确认,其中一些与其他语言关系并不密切。仅在2010年代被确认的独特语言包括科基那加语。

Randy LaPolla (2003) proposed a Rung branch of Tibeto-Burman, based on morphological evidence, but this is not widely accepted.

【参考译文】兰迪·拉波拉(Randy LaPolla)于2003年基于形态学证据提出了藏缅语的戎语支,但这并未被广泛接受。

Scott DeLancey (2015)[37] proposed a Central branch of Tibeto-Burman based on morphological evidence.

【参考译文】斯科特·德兰西(Scott DeLancey)于2015年[37]基于形态学证据提出了藏缅语的中部语支。

Roger Blench and Mark Post (2011) list a number of divergent languages of Arunachal Pradesh, in northeastern India, that might have non-Tibeto-Burman substrates, or could even be non-Tibeto-Burman language isolates:[27]

【参考译文】罗杰·布伦奇(Roger Blench)和马克·波斯特(Mark Post)于2011年列出了一系列印度东北部阿鲁纳恰尔邦的分歧语言,这些语言可能有非藏缅语的底层,甚至可能是非藏缅语的孤立语言:[27]

Blench and Post believe the remaining languages with these substratal characteristics are more clearly Sino-Tibetan:

【参考译文】布伦奇和波斯特认为,具有这些底层特征的其他语言更明确地属于汉藏语系:

3.8 杜冠明的分类

杜冠明(Thurgood 2003)的分类如下:

- 倮倮-缅

- 藏(Bodic)

- 萨尔(可能包含卢伊)

- 库基-钦-那加(暂定,包含曼尼普尔语)

- 戎

- 克伦

- 其他小分支:塔尼、舍朱奔-布贡-苏龙-利西巴、鲁索语支、义都-迪加罗、米教/格曼

- 未分类语言:骠语、纳西语、土家语、白语

3.9 孙宏开的分类

孙宏开(2015)比较了藏缅语言的语音、词汇和语法特点,根据远近关系将其划分为5个语群,共10个语支[5][6][7]:

分享到: