中文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

英文词条原文链接(无法从中国内地访问):请点击这里访问

本文基于英文词条的线索,并补充部分来自中文词条的内容(在二者冲突时,以更晚更新者为准)。辽观搬运时进行了必要的合规化处理,以使其能够在中国内地上传。部分文字采用汉语拼音方式代替,音节后的数字表示汉语拼音规则中的声调。

关于辽观的维基百科搬运计划,及根据名称精确检索已搬运的词条,请点击这里访问辽观网站。维基百科(Wikipedia)是美国维基媒体基金会的互联网百科项目,其内容可能受到立场、信息来源等因素影响,请客观看待。正文内容不代表译者观点。

辽观提供的翻译仅供参考。文中可能包含无法从中国内地访问的链接。

辽观所搬运的词条文本与维基百科一道同样遵循CC BY-SA 4.0协议(辽观搬运的中英文对照版本),在符合协议要求的情况下您可以免费使用其内容(包括商用)。图片和视频可能遵循不同的共享协议。请点击这里访问

The Thucydides Trap, or Thucydides’ Trap, is a term popularized by American political scientist Graham T. Allison to describe an apparent tendency towards war when an emerging power threatens to displace an existing great power as a regional or international hegemon.[1] The term exploded in popularity in 2015 and primarily applies to analysis of China–United States relations.[2]

【参考译文】修昔底德陷阱(Thucydides Trap)是美国政治学家格雷厄姆·T·艾利森普及的一个术语,用来描述当一个新兴大国威胁要取代现有大国成为地区或国际霸主时,双方明显趋向于发生战争的情况。[1]该术语在2015年迅速流行开来,主要应用于分析中美关系。[2]

修昔底德陷阱基于古雅典名将及历史学者修昔底德的一段话,修昔底德认为雅典和斯巴达之间的伯罗奔尼撒战争不可避免,因为斯巴达对雅典实力的增长心生恐惧。[3][4]为支持这论点,艾利森在哈佛大学贝尔弗科学与国际事务中心领导了一项研究,该研究发现,在新兴大国与现有霸主竞争的16件历史实例中,有12件最终以战争告终,然而这研究受到了相当大争议,学术界对修昔底德陷阱的理论意见不一。[5]

Supporting the thesis, Allison led a study at Harvard University‘s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs which found that, among a sample of 16 historical instances of an emerging power rivaling a ruling power, 12 ended in war.[3] That study, however, has come under considerable criticism, and scholarly opinion on the value of the Thucydides Trap concept—particularly as it relates to a potential military conflict between the United States and China—remains divided.[4][5][6][7][8]

【参考译文】艾利森为支持其论点,在哈佛大学贝尔弗科学与国际事务中心(Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs)主持了一项研究,该研究发现,在16个新兴大国与统治大国相抗衡的历史案例中,有12个以战争告终。[3]然而,该研究受到了诸多批评,学界对于修昔底德陷阱概念的价值——尤其是它与美中之间潜在军事冲突的相关性——仍然存在分歧。[4][5][6][7][8]

目录

1. 起源 | Origin

The concept stems from a suggestion by the ancient Athenian historian and military general Thucydides that the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta in 431 BC was inevitable because of the Spartans’ fear of the growth of Athenian power.[9][10]

【参考译文】该概念源自古希腊雅典历史学家兼军事将领修昔底德的一个观点,他认为公元前431年爆发的雅典与斯巴达之间的伯罗奔尼撒战争是不可避免的,因为斯巴达人害怕雅典势力的崛起。[9][10]

The term was coined by American political scientist Graham T. Allison in a 2012 article for the Financial Times.[2] Based on a passage by Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War positing that “it was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable”,[11][12] Allison used the term to describe a tendency towards war when a rising power (exemplified by Athens) challenges the status of a ruling power (exemplified by Sparta). Allison expanded upon the term significantly in his 2017 book Destined for War, in which he argued that “China and the US are currently on a collision course for war”.[13][2] Though Allison argues in Destined for War that war between a “ruling power” and “rising power” is not inevitable, war may be very difficult to avoid and requires extensive and intensive diplomatic attention and exertion in the case of a Thucydides trap.[13]

【参考译文】美国政治学家格雷厄姆·T·艾利森在2012年为《金融时报》撰写的一篇文章中创造了这个术语。[2]基于修昔底德在《伯罗奔尼撒战争史》中的一段文字,该文字提出“正是雅典的崛起以及这对斯巴达造成的恐惧使得战争不可避免”,[11][12]艾利森使用这个术语来描述当一个崛起的大国(以雅典为例)挑战一个统治性大国(以斯巴达为例)的地位时,双方容易趋向战争的情况。艾利森在其2017年的著作《战争宿命》中大大扩展了这个术语的内涵,他在书中论证道,“中国和美国目前正处于战争碰撞的轨道上”。[13][2]尽管艾利森在《战争宿命》一书中认为,“统治性大国”与“崛起大国”之间的战争并非不可避免,但一旦陷入修昔底德陷阱,战争将非常难以避免,并且需要广泛而深入的外交关注和努力。[13]

艾利森在其著作《注定的一战》(Destined For War)中进一步阐述,用这术语描述当时快速崛起的大国雅典,挑战现有强国斯巴达国际霸主的地位时,战争最后无可避免地爆发。他认为“中美两国目前正处于通往战争冲突的进程”[8][2]。

2. 定义 | Definition

The term describes the theory that when a great power’s position as hegemon is threatened by an emerging power, there is a significant likelihood of war between the two powers.[1][2] In Graham Allison’s words:

【参考译文】该术语描述的是这样一种理论:当一个大国的霸主地位受到新兴大国的威胁时,这两个大国之间极有可能爆发战争。[1][2]用格雷厄姆·艾利森的话来说:

Thucydides’s Trap refers to the natural, inevitable discombobulation that occurs when a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power…[and] when a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power, the resulting structural stress makes a violent clash the rule, not the exception.[13]: xv–xvi

【参考译文】修昔底德陷阱指的是,当一个新兴大国威胁要取代一个统治性大国的地位时,自然而然且不可避免地会出现混乱……而当一个新兴大国威胁要取代统治性大国的地位时,由此产生的结构性压力使得暴力冲突成为常态,而非例外。[13]:xv–xvi

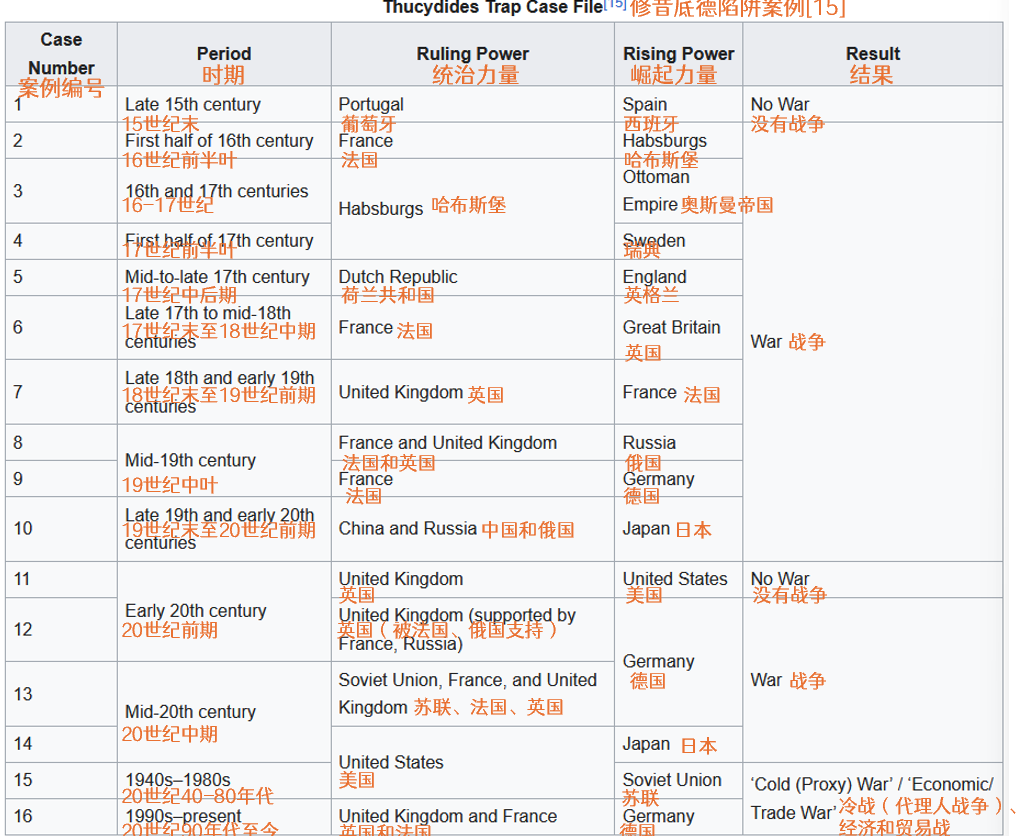

To advance his thesis, Allison led a case study by the Harvard University Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs which found that among 16 historical instances of an emerging power rivaling a ruling power, 12 ended in war.[a][9][14] The cases included in Allison’s original study are listed in the following table.

【参考译文】为了论证他的论点,艾利森(Allison)领导了哈佛大学贝尔弗科学与国际事务中心(Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs)进行的一项案例研究,该研究发现,在16个新兴大国与守成大国相互竞争的历史案例中,有12个最终引发了战争。[a][9][14]艾利森原始研究中包含的案例如下表所示。

【英文词条原注a】The study has faced considerable criticism. See § Methodological criticisms.

【参考译文】这项研究受到了相当多的批评。详见“方法论批评”部分。

3. 影响 | Influence

The term and arguments surrounding it have had influence in international media (including Chinese state media[16]) and among American and Chinese politicians.[2] A case study of the term by Alan Greeley Misenheimer published by the Institute for National Strategic Studies, the military research arm of the National Defense University, stated that it “has received global attention since entering the international relations lexicon”.[17] Foreign policy scholars Hal Brands and Michael Beckley have stated that the Thucydides Trap has “become canonical”, a “truism now invoked, ad nauseam, in explaining U.S.–China rivalry”.[18] Furthermore, BBC diplomatic correspondent Jonathan Marcus has quipped that Graham Allison’s book expanding on the Thucydides trap, Destined For War, “has become required reading for many policymakers, academics and journalists”.[19]

【参考译文】“修昔底德陷阱”这一术语及其相关论点在国际媒体(包括中国官方媒体[16])以及美国和中国的政界人士中产生了影响。[2]美国国防大学军事研究机构国家战略研究所(the Institute for National Strategic Studies)出版的艾伦·格里利·米森海默(Alan Greeley Misenheimer)对该术语的案例研究指出,它“自进入国际关系词典以来,就受到了全球的关注”。[17]外交政策学者哈尔·布兰兹(Hal Brands)和迈克尔·贝克利(Michael Beckley)指出,“修昔底德陷阱”已经“成为经典”,是“如今在解释美中竞争时被反复引用、令人厌烦的公理”。[18]此外,英国广播公司(BBC)的外交记者乔纳森·马库斯(Jonathan Marcus)曾风趣地说,格雷厄姆·艾利森(Graham Allison)围绕“修昔底德陷阱”展开论述的著作《注定一战》(Destined For War)“已成为许多决策者、学者和记者的必读之作”。[19]

3.1 中美关系 China–United States relations

Further information: China–United States relations / 更多信息:中美关系

The term is primarily used and was coined in relation to a potential military conflict between the United States and the People’s Republic of China.[2] Chinese leader and CCP general secretary Xi Jinping referenced the term, cautioning that “We all need to work together to avoid the Thucydides trap.”[20] The term gained further influence in 2018 as a result of an increase in US-Chinese tensions after US President Donald Trump imposed tariffs on almost half of China’s exports to the US, leading to a trade war.[2][21]

【参考译文】这一术语主要用于描述美国和中华人民共和国之间可能发生的军事冲突。[2] 中国领导人、中共总书记习近平提到这一术语时警告称:“我们要共同努力,避免陷入修昔底德陷阱”。[20] 2018 年,美国总统唐纳德·特朗普对中国近一半输美产品加征关税,引发贸易战,中美紧张局势加剧,这一术语的影响力进一步增强。[2][21]

Western scholars have noted that there are a number of pressing issues the two nations are at odds over that increase the likelihood of the two powers falling into the Thucydides trap, including the continued de facto independence of Taiwan supported by Western countries, China’s digital policing and its use of cyber espionage, differing policies towards North Korea, China’s increased naval presence in the Pacific and its claims over the South China Sea, and human rights issues in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong.[1][19][21][22] Some also point to the consolidation of power by Xi Jinping, the belief in an irreconcilable differences in values, and the trade deficit as further evidence the countries may be slipping into the Thucydides trap.[21][23]

【参考译文】西方学者指出,中美两国在许多紧迫问题上存在分歧,这些问题增加了两国陷入“修昔底德陷阱”的可能性,包括西方国家支持台湾继续保持事实上的独立,中国的数字警察和网络间谍活动,中美对朝鲜的不同政策,中国在太平洋增强海军存在并主张南海主权,以及新疆、西藏和香港的人权问题。[1][19][21][22] 一些人还指出,习近平的权力巩固、对不可调和的价值观差异的信念以及贸易逆差也进一步证明两国可能正在陷入“修昔底德陷阱”。[21][23]

4. 批评 | Criticism

4.1 中美关系 | China–United States relations

A number of scholars have criticized the application of the Thucydides trap to US–China relations. Lawrence Freedman, writing in Prism, the National Defense University‘s journal of complex operations, has similarly argued that “China’s main interest has always been its regional position, and if that is the case, then there are strong arguments for it to show patience, as its economic pull becomes progressively stronger.”[24] Hu Bo, a professor at Peking University‘s Institute of Ocean Research and one of China’s foremost naval strategists, has also said that he does not believe the current balance of power between the United States and China supports the Thucydides hypothesis.[19]

【参考译文】一些学者对将“修昔底德陷阱”应用于中美关系提出了批评。劳伦斯·弗里德曼(Lawrence Freedman)在《国家防务大学学报:复杂行动》(Prism)中写道,他同样认为“中国的主要利益一直是其地区地位,如果情况确实如此,那么随着中国经济实力的逐步增强,中国有耐心这一论点就很有说服力”。[24]北京大学海洋研究院教授、中国顶尖海军战略家之一胡波也表示,他不认为当前美国和中国之间的力量平衡支持“修昔底德陷阱”假说。[19]

Scholars and journalists like Arthur Waldron and Ian Buruma have contended that China is still far too weak for such a conflict, pointing to China’s “economic vulnerabilities”, its aging population, an exodus of Chinese people out of China, domestic ecological problems, an inferior military relative to the United States, a weaker system of alliances than the United States, and a censorship regime that limits innovation.[25][26] Foreign policy scholars Hal Brands and Michael Beckley have similarly argued that the Thucydides Trap “fundamentally misdiagnoses where China now finds itself on its arc of development”, contending that it is China—and not the United States—that faces impending stagnation.[18] Relatedly, Harvard University political scientist Joseph S. Nye has argued that the primary concern is not the rise of China leading to a Thucydides trap, but rather domestic issues leading to a weakening of China in what he calls a “Kindleberger Trap”.[22][27]

【参考译文】学者和记者如亚瑟·沃尔德伦(Arthur Waldron)和伊恩·布鲁玛(Ian Buruma)认为,中国仍然太弱,无法挑起这样的冲突,他们指出中国的“经济脆弱性”、人口老龄化、人口外流、国内生态问题、相对于美国的军事劣势、较弱的联盟体系,以及限制创新的审查制度。[25][26]外交政策学者哈尔·布兰兹(Hal Brands)和迈克尔·贝克利(Michael Beckley)也持类似观点,他们认为“修昔底德陷阱”从根本上“误诊了中国当前在其发展轨迹上的位置”,并认为是中国——而非美国——面临停滞不前的困境。[18]与此相关的是,哈佛大学政治学家约瑟夫·奈(Joseph S. Nye)认为,主要担忧的不是中国的崛起导致“修昔底德陷阱”,而是国内问题导致中国衰弱,他称之为“金德尔伯格陷阱”。[22][27]

Others have derided the Thucydides Trap as a quaint piece of ancient history that is not particularly applicable to modern times. James Palmer, a deputy editor at Foreign Policy, in his article “Oh God, Not the Peloponnesian War Again”, wrote of the Thucydides Trap that “conflicts between city-states in a backwater Eurasian promontory 2,400 years ago are an unreliable guide to modern geopolitics—and they neglect a vast span of world history that may be far more relevant”.[28] He further derisively noted that Thucydides should not “hold the same grip on international relations scholars that Harry Potter does on millennial readers”. Lawrence Freedman has similarly argued that “[t]he case studies deployed by Allison”, which “come from times when issues of war and power were viewed differently than they are today”, tell us “very little of value”, concluding that “the Thucydides Trap is an unhelpful construct”.[24]

【参考译文】另一些人则嘲笑“修昔底德陷阱”不过是古代历史中的一段奇闻,并不特别适用于现代。外交政策杂志副主编詹姆斯·帕尔默(James Palmer)在文章《哦,上帝,别再是伯罗奔尼撒战争了》中谈到“修昔底德陷阱”时写道:“2400年前欧亚大陆一个偏远海角上的城邦之间的冲突,对现代地缘政治来说并不可靠的指导——它们忽略了可能更加相关的漫长世界历史”。[28]他进一步嘲讽道,修昔底德不应该“像《哈利·波特》对千禧一代读者那样,对国际关系学者产生同样的吸引力”。劳伦斯·弗里德曼(Lawrence Freedman)也持类似观点,他认为艾利森“所使用的案例研究来自与今天对战争和权力问题看法不同的时代”,它们“几乎没有什么有价值的东西可讲”,并得出结论:“修昔底德陷阱是一个无用的构想”。[24]

Scholar David Daokai Li writes that the Thucydides Trap theory is flawed as applied to U.S.–China relations, because the model is based on Western and Ancient Greek analogies.[29] In Li’s view, examples such as Germany in the 1910s are considerably different from contemporary China.[29]

【参考译文】学者李大凯(David Daokai Li)写道,将“修昔底德陷阱”理论应用于中美关系是有缺陷的,因为这个模型是基于西方和古希腊的类比。[29]在李大凯看来,20世纪10年代的德国与当代中国有很大不同。[29]

Finally, some have noted that Chinese state propaganda outlets have latched onto the narrative of the Thucydides Trap in order to promote a set of power relations that favors China.[30][31]

【参考译文】最后,一些人指出,中国的国家宣传机构已经抓住了“修昔底德陷阱”的叙事,以推动一套有利于中国的权力关系。[30][31]

4.2 方法论批评 | Methodological criticisms

4.2.1 对修昔底德陷阱研究的批评 | Criticism of research into Thucydides Trap

The research by Graham Allison supporting the Thucydides trap has been criticized. Harvard University political scientist Joseph S. Nye has contested the claim that 12 of the 16 historical cases of a rising power rivaling a ruling power resulted in war on the basis that Allison misidentifies cases.[27] For example, he points to the case of World War I, which Allison identifies as an instance of an emerging Germany rivaling a hegemonic Britain, saying that the war was also caused by “the fear in Germany of Russia’s growing power, the fear of rising Slavic nationalism in a declining Austria-Hungary, as well as myriad other factors that differed from ancient Greece”.

【参考译文】格雷厄姆·艾利森(Graham Allison)支持修昔底德陷阱的研究受到了批评。哈佛大学政治学家约瑟夫·奈(Joseph S. Nye)对艾利森提出的16个历史案例中,有12个崛起大国与守成大国的竞争最终引发战争的说法提出了质疑,他认为艾利森误判了一些案例。[27]例如,他指出了艾利森将第一次世界大战视为新兴德国与霸权英国竞争的案例,并表示战争的原因还包括“德国对俄罗斯日益增长的力量的恐惧、衰落中的奥匈帝国对斯拉夫民族主义崛起的恐惧,以及许多与古希腊不同的其他因素”。

Historian Arthur Waldron has similarly argued that Allison mischaracterizes several conflicts.[26] For example, he says of the Japan–Russia conflict included by Allison: “Japan was the rising power in 1904 while Russia was long established. Did Russia therefore seek to preempt Japan? No. The Japanese launched a surprise attack on Russia, scuttling the Czar’s fleet.” Lawrence Freedman, writing in Prism, the National Defense University‘s journal of complex operations, has likewise argued that Allison misunderstands the causes of several of his case studies, particularly World War I, which he argues resulted more from “the dispute between Austria and Serbia, and its mismanagement by their allies, Germany and Russia”.[24]

【参考译文】历史学家亚瑟·沃尔德伦(Arthur Waldron)也指出艾利森对几场冲突的描述有误。[26]例如,对于艾利森提到的日俄冲突,他说:“1904年时,日本是崛起中的大国,而俄罗斯早已确立地位。因此,俄罗斯是否试图先发制人?不是。是日本对俄罗斯发动了突袭,击沉了沙皇的舰队。”劳伦斯·弗里德曼(Lawrence Freedman)在《国家防务大学学报:复杂行动》(Prism)中写道,艾利森误解了他所研究的几个案例的原因,尤其是第一次世界大战,他认为这场战争更多是由于“奥地利和塞尔维亚之间的争端,以及它们的盟友德国和俄罗斯处理不当”造成的。[24]

Foreign policy scholars Hal Brands and Michael Beckley have argued that, for many of the cases Allison identifies with the Thucydides Trap, the impetus that led to war was not the impending threat of a hegemonic power being surpassed but rather an emerging power lashing out when its rapid rise transmogrified into stagnation.[18] They write:

【参考译文】外交政策学者哈尔·布兰兹(Hal Brands)和迈克尔·贝克利(Michael Beckley)认为,在艾利森用修昔底德陷阱理论来解释的许多案例中,导致战争发生的动因并非霸权国家即将被超越的紧迫威胁,而是新兴国家在其快速崛起转变为停滞不前时采取的激烈反击。[18]他们写道:

[T]he calculus that produces war—particularly the calculus that pushes revisionist powers, countries seeking to shake up the existing system, to lash out violently—is more complex (than the Thucydides Trap). A country whose relative wealth and power are growing will surely become more assertive and ambitious. All things equal, it will seek greater global influence and prestige. But if its position is steadily improving, it should postpone a deadly showdown with the reigning hegemon until it has become even stronger…Now imagine a different scenario. A dissatisfied state has been building its power and expanding its geopolitical horizons. But then the country peaks, perhaps because its economy slows, perhaps because its own assertiveness provokes a coalition of determined rivals, or perhaps because both of these things happen at once. The future starts to look quite forbidding; a sense of imminent danger starts to replace a feeling of limitless possibility. In these circumstances, a revisionist power may act boldly, even aggressively, to grab what it can before it is too late. The most dangerous trajectory in world politics is a long rise followed by the prospect of a sharp decline.

引发战争的各种考虑——特别是促使谋求改变势力(此处指寻求动摇现有体系的势力)进行暴力攻击的各种考虑——比单纯的修昔底德陷阱更复杂。 一个相对财富和实力不断增长的国家肯定会变得更加自信和雄心勃勃。 在其他条件相同的情况下,它将寻求更大的全球影响力和威望。 但如果它的地位正在稳步提高,它应该推迟与卫冕霸主的致命对决,直到它变得更加强大……现在想象一下不同的场景。 一个不满的国家一直在增强其实力并扩大其地缘政治视野。 但随后这个国家的颠峰期过去,也许是因为经济放缓,也许是因为它自己的过度自信挑起了竞争对手的坚决联盟,或者也许是因为这两件事同时发生。 未来开始显得相当严峻。 迫在眉睫的危险感开始取代自己有无限可能性的感觉。 在这种情况下,谋求改变势力可能会采取大胆甚至激进的行动,在为时已晚之前攫取其所能的一切。 世界政治中最危险的轨迹是长期上升,然后出现一个急剧衰退的预期。

They claim that several of Allison’s cases in fact follow this pattern—and not that of the Thucydides Trap—including the Russo-Japanese War, World War I, and the Pacific War (they also point to America’s imperial foray after the American Civil War and modern-day Russia under Vladimir Putin). They further claim that it is this effect that is more likely to push the United States and China into conflict, as China is “slowing economically and facing growing global resistance”.

【参考译文】他们声称,艾利森的几个案例实际上遵循的是这一模式——而非修昔底德陷阱的模式——包括日俄战争、第一次世界大战和太平洋战争(他们还指出了美国内战后的帝国主义扩张以及弗拉基米尔·普京领导下的现代俄罗斯)。他们进一步声称,正是这种效应更有可能将美国和中国推向冲突,因为中国“经济正在放缓,并面临着日益增长的全球阻力”。

Classicist Victor Davis Hanson challenges the theory, noting that a rising power does not always provoke a preemptive attack from an established power. He cites fundamental differences between states as a key factor, explaining why such a dynamic did not emerge between the UK and the US despite the latter’s rise but is evident in the tensions between the US and China due to their contrasting political and economic systems.[32]

【参考译文】古典学者维克多·戴维斯·汉森(Victor Davis Hanson)对该理论提出了质疑,他指出,崛起的大国并不总是会引发既成大国先发制人的攻击。他引用了国家之间的根本差异作为关键因素,解释了尽管美国崛起,但英美之间为何没有出现这种动态,而美中之间由于政治和经济体制的不同,紧张关系却显而易见。[32]

4.2.2 伯罗奔尼撒战争 | Peloponnesian War

In addition to criticizing Allison’s knowledge of east Asian history, reviewers also criticized his knowledge of ancient Greek history.[33]: 184–185 Harvard University political scientist Joseph S. Nye, pointing to research by Yale historian Donald Kagan, has argued that Graham Allison misinterprets the Peloponnesian War; Nye argues that the war was not the result of a rising Athens challenging Sparta, but rather the consequence of Athenian stagnation leading Sparta to think that a number of “Athenian policy mistakes” made war “worth the risk”.[27] Historian Arthur Waldron likewise argued that Kagan and Harvard classics scholar Ernst Badian had “long ago proved that no such thing exists as the ‘Thucydides Trap'” with regards to the Peloponnesian War.[26] Relatedly, political scientists Athanassios Platias and Vasilis Trigkas submitted that the Thucydides Trap is based on “inadvertent escalation” whereas the Peloponnesian war was an outcome of rational calculations.[34]

【参考译文】除了批评艾利森对东亚历史的知识外,评论家还批评了他对古希腊历史的知识。[33]:184–185哈佛大学政治学家约瑟夫·奈(Joseph S. Nye)指出耶鲁大学历史学家唐纳德·卡根(Donald Kagan)的研究,认为格雷厄姆·艾利森误解了伯罗奔尼撒战争;奈认为,这场战争并不是因为崛起的雅典挑战斯巴达的结果,而是雅典的停滞不前让斯巴达认为雅典的一系列“政策错误”使得战争“值得冒险”。[27]历史学家亚瑟·沃尔德伦(Arthur Waldron)同样认为,就伯罗奔尼撒战争而言,卡根和哈佛大学古典学者恩斯特·巴迪安(Ernst Badian)“很久以前就已证明,所谓的‘修昔底德陷阱’根本不存在”。[26]与此相关的是,政治学家阿塔纳西奥斯·普拉提亚斯(Athanassios Platias)和瓦西里斯·特里加斯(Vasilis Trigkas)提出,修昔底德陷阱基于“无意的升级”,而伯罗奔尼撒战争则是理性计算的结果。[34]

Others have questioned Allison’s reading of Thucydides. In a case study for the Institute for National Strategic Studies, the military research arm of the National Defense University, Alan Greeley Misenheimer says that “Thucydides’ text does not support Allison’s normative assertion about the ‘inevitable’ result of an encounter between ‘rising’ and ‘ruling’ powers” and that while it “draws welcome attention both to Thucydides and to the pitfalls of great power competition” it “fails as a heuristic device or predictive tool in the analysis of contemporary events”.[17]

【参考译文】其他人也对艾利森对修昔底德的理解提出了质疑。在国家国防大学军事研究机构国家战略研究所的一项案例研究中,艾伦·格里利·米森海默(Alan Greeley Misenheimer)表示,“修昔底德的文本并不支持艾利森关于‘崛起国’与‘统治国’相遇‘必然’导致的结果的规范性断言”,虽然它“成功地将人们的注意力引向修昔底德和大国竞争的陷阱”,但“它作为分析当代事件的启发式工具或预测工具却失败了”。[17]

Academic Jeffrey Crean writes that Allison misunderstands the core lesson of Thucydides, that the greatest threat to a hegemon comes from within.[33]: 184–185 Thucydides couched his history as a dramatic tragedy, with the turning point coming when a hubristic Athens sought to conquer Syracuse, which was far from any Athenian possessions or interests.[33]: 185 For Thucydides, the Athenian attempt to conquer Syracuse was an example of democracy devolving into mob psychology and a failure that ultimately allowed Sparta to win.[33]: 185

【参考译文】学者杰弗里·克兰(Jeffrey Crean)写道,艾利森误解了修昔底德的核心教训,即对一个霸权国家最大的威胁来自其内部。[33]:184–185修昔底德将其历史描述为一部戏剧性的悲剧,转折点出现在傲慢的雅典试图征服远离其任何领土或利益的叙拉古时。[33]:185对修昔底德来说,雅典试图征服叙拉古是民主蜕变为群体心理的一个例子,也是一个最终的失败,它让斯巴达得以获胜。[33]:185

A. 参见(维基百科的相关词条)| See also

- China’s peaceful rise【中国的和平崛起】

- Chinese Century【中国的世纪】

- Historic recurrence【历史性复发】

- Offshore balancing【离岸平衡】

- Potential superpowers / 潜在超级大国

- Power transition theory【权力转移理论】

- 安全困境

- 中美贸易战

- 中国崛起

- 中美关系

B. 英文词条参考文献 | References

- ^ Mohammed, Farah (5 November 2018). “Can the U.S. and China Avoid the Thucydides Trap?”. JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Rachman, Gideon (18 December 2018). “Year in a Word: Thucydides’s trap”. Financial Times. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Allison, Graham (9 June 2017). “The Thucydides Trap”. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

The past 500 years have seen 16 cases in which a rising power threatened to displace a ruling one. Twelve of these ended in war.

- ^ Freedman, Lawrence (12 January 2022). “What the Thucydides Trap gets wrong about China”. New Statesman. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Mohammed, Farah (5 November 2018). “Can the US and China Avoid the Thucydides Trap?”. JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ McCormack, Win (17 March 2023). “The Thucydides Trap”. The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Allison, Graham (24 September 2015). “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?”. The Atlantic. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ “Stop seeing US-China relations through lens of Thucydides or Cold War”. South China Morning Post. 10 December 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Allison, Graham (24 September 2015). “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?”. The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Allison, Graham (9 June 2017). “The Thucydides Trap”. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Allison, Graham (21 August 2012). “Thucydides’s trap has been sprung in the Pacific”. Financial Times. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Thucydides. “The History of the Peloponnesian War”. The Internet Classics Archive. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Allison, Graham (2017). Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-1328915382.

- ^ “Thucydides’s Trap”. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard Kennedy School. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ “Thucydides’s Trap”. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard Kennedy School. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Yongding, Yu; Gallagher, Kevin P. (11 May 2020). “Virus offers a way out of Thucydides trap”. China Daily. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Misenheimer, Alan Greeley (4 June 2019). “Thucydides’ Other “Traps”: The United States, China, and the Prospect of “Inevitable” War”. Institute for National Strategic Studies. National Defense University. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Brands, Hal; Beckley, Michael (24 September 2021). “China Is a Declining Power—and That’s the Problem”. Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (25 March 2019). “Could an ancient Greek have predicted a US-China conflict?”. BBC. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Valencia, Mark J. (7 February 2014). “China needs patience to achieve a peaceful rise”. South China Morning Post. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Kant, Ravi (26 February 2020). “The 21st-century Thucydides trap”. Asia Times. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Funabashi, Yoichi (10 October 2017). “Can we avoid the ‘Thucydides Trap’?”. Japan Times. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Yu, David; Yap, Wy-En (21 February 2020). “Can U.S. And China Escape The Thucydides Trap?”. Forbes. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Freedman, Lawrence (14 September 2017). “Book Review : Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?”. PRISM. National Defense University. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Buruma, Ian (12 June 2017). “Are China and the United States Headed for War?”. The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Waldron, Arthur (12 June 2017). “There is no Thucydides Trap”. SupChina. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Nye, Joseph S. (9 January 2017). “The Kindleberger Trap”. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard Kennedy School. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Palmer, James (28 July 2020). “Oh God, Not the Peloponnesian War Again”. Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Li, David Daokui (2024). China’s World View: Demystifying China to Prevent Global Conflict. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 238. ISBN 978-0393292398.

- ^ Cole, J. Michael; Hsu, Szu-Chien (2020). Insidious Power: How China Undermines Global Democracy. Eastbridge Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-78869-214-4.

- ^ Parton, Charles (13 May 2024). “The Harvard man who became Xi Jinping’s favourite academic”. The Spectator. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ “Secrets Of Statecraft: What The Greeks And Romans Can Teach Us”. Hoover Institution. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Crean, Jeffrey (2024). The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History. New Approaches to International History series. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-23394-2.

- ^ Platias, Athanasios; Trigkas, Vasilis (2021). “Unravelling the Thucydides Trap: Inadvertent Escalation or War of Choice”. Chinese Journal of International Politics. 14, Issue 2, Summer 2021 (2): 219–255. doi:10.1093/cjip/poaa023.

C. 中文词条参考文献

- ^ Mohammed, Farah. Can the U.S. and China Avoid the Thucydides Trap?. JSTOR Daily. 5 November 2018 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-01-01).

- ^ Rachman, Gideon. Year in a Word: Thucydides’s trap. 18 December 2018 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-16).

- ^ Allison, Graham. The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?. The Atlantic. 24 September 2015 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-17).

- ^ Allison, Graham. The Thucydides Trap. Foreign Policy. 9 June 2017 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2019-10-05).

- ^ Wang, William Ziyuan. Destined for Misperception? Status Dilemma and the Early Origin of US-China Antagonism. Journal of Chinese Political Science (Springer). 2019 [2022-12-31]. (原始内容存档于2022-12-31).

- ^ Allison, Graham. Thucydides’s trap has been sprung in the Pacific. Financial Times. 21 August 2012 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-07).

- ^ Thucydides. The History of the Peloponnesian War. The Internet Classics Archive. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [431 BCE] [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-04-07).

- ^ Allison, Graham. Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2017. ISBN 978-1328915382.

- ^ Allison, Graham. Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2017: xv–xvi. ISBN 978-1328915382.

- ^ Thucydides’s Trap. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard Kennedy School. [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-05).

- ^ Yongding, Yu; Gallagher, Kevin P. Virus offers a way out of Thucydides trap. China Daily. 11 May 2020 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于25 May 2020).

- ^ Misenheimer, Alan Greeley. Thucydides’ Other “Traps”: The United States, China, and the Prospect of “Inevitable” War. Institute for National Strategic Studies. National Defense University. 4 June 2019 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2021-09-09).

- ^ Valencia, Mark J. China needs patience to achieve a peaceful rise. South China Morning Post. 7 February 2014 [8 July 2019]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-21).

- ^ Kant, Ravi. The 21st-century Thucydides trap. Asia Times. 26 February 2020 [8 July 2020]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-27).

- ^ Brands, Hal; Beckley, Michael. China Is a Declining Power—and That’s the Problem. Foreign Policy. September 24, 2021 [September 29, 2021]. (原始内容存档于September 28, 2021).

分享到: